Data acquisition

Here we give further relevant details on the experimental scheme and apparatus (both described in detail in ref. 23). The run time of the cryogenic atomic beam is limited to freezing cycles of approximately 2 h by the accumulation of frozen (molecular) hydrogen inside the nozzle, which is removed by heating the nozzle to room temperature. The vacuum (2 × 10−7 mbar, dominated by molecular hydrogen) inside the 2S–6P spectroscopy region is maintained by differential pumping with a cryopump to minimize pressure shifts50,51,52, with the temperature of the apparatus allowed to equilibrate on each measurement day before collecting data.

The power of the linearly polarized, 243-nm 1S–2S preparation laser53,54 is resonantly enhanced in an in-vacuum, standing-wave cavity to P1S–2S ≈ 1 W per direction (297 μm 1/e2 intensity waist radius). The observed 1S–2S transition linewidth is approximately 3 kHz (FWHM; atomic detuning, as opposed to laser detuning), limited by single-photon ionization of the 2S level55. Therefore, the \(2\rmS_1/2^F=1\) levels are only populated by Doppler-sensitive two-photon excitation, leading to a population of approximately 7 × 10−7 in each sublevel relative to the population in the \(2\rmS_1/2^F=0\) level. The detuning of the preparation laser is set several times per freezing cycle by observing the 1S–2S transition. An equal-slit-width optical chopper running at 160 Hz periodically blocks the preparation laser (which sets delay time τ = 0 μs) to enable the velocity-resolved detection. The channel electron multipliers are switched off with a fast high-voltage switch while the preparation laser is unblocked to prevent saturation from scattered 243-nm light.

By using a linearly polarized 2S–6P spectroscopy laser53,54 and the \(2\rmS_1/2^F=0\) level as the initial level, only transitions to the \(6\rmP_1/2^F=1\) hyperfine level (2S–6P1/2 transition) and the \(6\rmP_3/2^F=1\) hyperfine level (2S–6P3/2 transition) are dipole-allowed, whereas the excitation of the \(6\rmP_1/2^F=0\) and \(6\rmP_3/2^F=2\) levels is prevented by angular momentum conservation (Fig. 2a). The line strengths (∝μ2, in which μ is the dipole moment) of the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions have a 1:2 ratio. We use spectroscopy laser powers P2S–6P with a ratio of 2:1 for the two transitions to keep their Rabi frequencies \(\varOmega _\propto \mu \sqrtP_2\rmS-6\rmP\) identical (the peak Rabi frequency is (2π × 126) krad s−1 at our highest spectroscopy laser powers of 30 and 15 μW, respectively). Most 6P decays (branching ratio Γe–1S/Γ = 88.2%) are Lyman decays to the 1S manifold, with the most energetic, direct Lyman-ε decay (Γdet/Γ = 80.5%) dominating, whereas the remaining γe–2S/Γ = 11.8% are Balmer decays to the 2S manifold, of which in turn a fraction γei/Γ leads back to the initial \(2\rmS_1/2^F=0\) level (see Section 1.2 in the Supplementary Methods). The metastable 2S levels are treated as stable here, as their natural lifetime (122 ms) is much longer than the time the atoms spend in the atomic beam (see Section 2.6 in the Supplementary Methods for the 2S decay contribution to the signal background).

The channel electron multipliers count the fluorescence photons from the 6P decays, either by detecting the photoelectrons emitted by the photons from the detector cylinder walls or, to a lesser extent, directly detecting the photons. Because the photoelectron yield strongly increases with photon energy (for both colloidal graphite and oxidized aluminium, the surface materials of the Faraday cage and the detector cylinder, respectively), fluorescence from Lyman-ε decay (13.2 eV photon energy) constitutes approximately 97% of the signal detected by the channel electron multipliers. The counts are binned into the 16 velocity groups by their delay time τ, with the bins chosen to cover a wide range of mean speeds \(\overlinev\) while exhibiting a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio (bin width 50–550 μs; Extended Data Table 2). For each line scan, we accumulate counts over 160 chopper cycles at each spectroscopy laser detuning. Intermittently, excess scatter and spiking was observed for the bottom detector and its signal was subsequently discarded (≈11% of line scans; Extended Data Table 3). We attribute this to the bottom detector being cooled down to close to, and possibly below, its lower operating temperature limit because of its vicinity to the cryopump.

At least once per measurement day, the nozzle and the collimating aperture are centred on the preparation laser. At the start of each freezing cycle, the atomic beam offset angle α0, which is controlled by a linear motor equipped with a position sensor, is aligned to zero with a 1 mrad alignment uncertainty. This is achieved by blocking the returning beam of the spectroscopy laser (using an in-vacuum shutter in front of the high-reflectivity mirror of the AFR25,26), determining the (now unsuppressed) Doppler slope κ for several angles and moving to the angle at which κ is zero, which is set as α0 = 0 mrad. To record line scans at a non-zero angle ±α0, we first move to either +α0 or −α0 (chosen randomly) and then to the opposite sign, recording typically 5–10 scans at each angle, and repeating this procedure several times per freezing cycle. The fibre–collimator distance of the AFR is optimized25,26 at least once per freezing cycle.

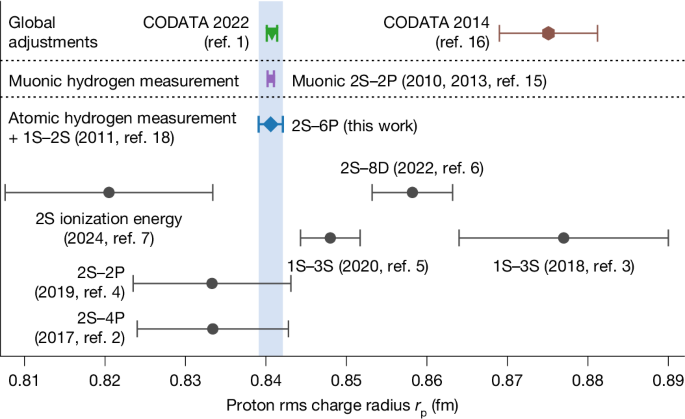

We use fixed sets of 30 symmetric (15 unique) detunings Δ of the spectroscopy laser frequency to sample the 2S–6P fluorescence line shape, with different sets used for α0 = 0, ±7.5 and ±12 mrad to account for the different line shapes (see Section 5.1.3 and Table 5.2 of ref. 23), all of which have ±50 MHz as the largest detuning. The detunings were chosen to minimize the statistical uncertainty of the Doppler-free transition frequency νe, whereas the number of detunings and the acquisition time (1 s) at each detuning were chosen to balance between sufficient line sampling, signal-to-noise ratio and number of line scans per freezing cycle. For each line scan, the order of the detunings is randomized to minimize the influence of drifts in the signal. At the beginning of each freezing cycle, the centre laser frequency (to which the detunings are added) was chosen randomly from a normal distribution. This distribution was centred on the 2S–6P transition frequency expected from the muonic measurement of the proton radius9, with a standard deviation of 12 kHz to cover the transition frequency expected from the CODATA 2014 value of the proton radius16. The laser frequencies are referenced to the caesium frequency standard using an optical frequency comb56,57 and a global navigation satellite system (GNSS)-referenced hydrogen maser (see Section 2.7 in the Supplementary Methods).

We switched between examining the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions several times during the measurement, except during measurement run C, for which only the 2S–6P1/2 transition was examined for several values of α0 (Extended Data Table 3).

Voigt and Voigt doublet line shapes

A Voigt line shape23,58 is the convolution of a Lorentzian line shape (with FWHM linewidth ΓL) and a Gaussian line shape (with FWHM linewidth ΓG). It has a combined FWHM linewidth \(\varGamma _\rmF\approx 0.5346\varGamma _\rmL\,+\) \(\sqrt{0.2166\varGamma _\rmL^2+\varGamma _\rmG^2}\) (ref. 59) and amplitude A and is centred on the resonance frequency ν0. A constant offset y0 is added to account for the experimentally observed signal background, resulting in five free parameters.

The Voigt doublet line shape is here defined as the sum of two Voigt line shapes with generally different resonance frequencies ν1 and ν2 and amplitudes A1 and A2 but equal Lorentzian and Gaussian linewidths23 (and a constant offset y0), resulting in seven free parameters. Its resonance frequency is the centre of mass of the constituent line shapes, that is, ν0 = (A1ν1 + A2ν2)/(A1 + A2).

Data analysis

The resonance frequency ν0 of each velocity group and detector of each line scan is determined by least-square fitting Voigt line shapes to the signal (for data with α0 = 0 mrad, that is, data groups G1A–G12). For data with α0 ≠ 0 mrad (data groups G13 and G14), in which the line can split into two Doppler components, the Voigt doublet line shape is used instead. For the fits, we assume the uncertainty on the signal yj, that is, the number of fluorescence photons detected at detuning j, to be the photon-number shot (Poissonian) noise, given by \(\sqrty_j\) (because yj ≫ 1, the Poisson distribution can be approximated with a normal distribution).

We use reduced chi-squared \(\chi _\rmred^2=\chi ^2/k\) (with k degrees of freedom) as a measure of the goodness of fit. The average \(\chi _\rmred^2\) is expected to be 1 if the fitted line shapes exactly match the experimental line shapes and if the signal fluctuations are fully described by shot noise. We first discuss the Voigt fits (k = 25), for which we find \(\chi _\rmred^2\) to be substantially larger than 1 (up to \(\chi _\rmred^2\approx 4.6\) at our highest spectroscopy laser power) for all but the slowest velocity groups. Only for those velocity groups, which have a comparatively lower signal and Doppler broadening, does \(\chi _\rmred^2\) approach 1 (\(\chi _\rmred^2\approx 1.1\) for τ16 for all data groups).

We identify two distinct contributions to the increased \(\chi _\rmred^2\). First, there are small model deviations between the fitted and experimental line shapes, caused by non-Gaussian (and non-Lorentzian) broadening and saturation effects not included in the former and clearly observable in the fit residuals (up to approximately 2% deviation; see black circles at the top of Extended Data Fig. 1b). Our simulated line shapes (both LFS and QI simulations) include these effects and consequently show much better agreement with the experimental line shapes (see dashed and solid lines in Extended Data Fig. 1b). We use this to determine the effect of the deviations on \(\chi _\rmred^2\) by repeating the line shape fits using simulated data instead of experimental data. In this Monte Carlo simulation, the appropriate line shape simulation is scaled and offset to match the experimental data of each line scan and then shot noise is added to the simulated signal. The simulated \(\chi _\rmred^2\) values reproduce, and therefore the deviations explain, approximately 70% of the excess (that is, \(\chi _\rmred^2-1\)) in the experimental \(\chi _\rmred^2\) values.

Second, there are fluctuations in the signal that lead to excess (technical) noise above shot noise, which we attribute to fluctuations in the atomic flux (of metastable 2S atoms). In particular, we identify correlations between \(\chi _\rmred^2\) of a line scan and fluctuations of the nozzle temperature (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.45) and the preparation laser power (r = 0.26) during the line scan, both of which directly affect the number of 2S atoms reaching the spectroscopy region. The correlation with the spectroscopy laser power is much smaller (r = 0.03). We find that the simple assumption of a velocity-group-independent, 1% rms fluctuation of the signal from detuning to detuning explains, on average, the remaining excess of the experimental \(\chi _\rmred^2\) values.

The \(\chi _\rmred^2\) behaviour is very similar for the Voigt doublet fits (k = 23) to the α0 = ±7.5 mrad data (data group G13). For the α0 = ±12 mrad data (data group G14), the two Doppler components start to separate, particularly for fast velocity groups (Fig. 3c). This leads to large model deviations (up to 14%; see bottom of Extended Data Fig. 1b) from saturation effects, as some atoms interact with both spectroscopy laser beams (|Δ| ≲ Γ2P), whereas others only interact with one beam (|Δ| ≳ Γ2P). Consequently, \(\chi _\rmred^2\) can exceed 20, which is largely explained (90% of excess) by the deviations, as again determined from the Monte Carlo simulation.

Asymmetric (about the line centre) deviations between the fitted and experimental line shapes, arising as a result of LFS and QI, do not substantially influence \(\chi _\rmred^2\) because of their small size. However, both symmetric and asymmetric deviations lead to a sampling bias, as discussed in Section 2.5 in the Supplementary Methods.

The uncertainty of the experimental resonance frequency ν0 is estimated from the line shape fits assuming only shot noise, that is, the technical noise is not taken into account at this point. The value of ν0 for each velocity group and detector of each line scan is corrected for the LFS and QI shift by subtracting, respectively, νLFS and νQI, which are determined from the corresponding simulated line shapes (see Section 1.1 in the Supplementary Methods). The mean speed \(\overlinev\) and rms speed \(\overlinev_\rmrms\) of each velocity group are also determined from these simulated line shapes (see Section 1.1 in the Supplementary Methods; Extended Data Table 2 gives the average value of \(\overlinev\) for each velocity group). The second-order Doppler shift ΔνSOD is calculated using \(\overlinev_\rmrms\) (see Section 2.1 in the Supplementary Methods) and likewise subtracted from ν0.

Next, using the simulated values of the speed \(\barv\), the Doppler shift extrapolation is performed to find the Doppler-free transition frequency νe and the Doppler slope κ. The values νe and κ found for each line scan are inherently strongly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient re ≈ −0.97) and their uncertainties are found by propagating the uncertainties of ν0. Although the averaging process outlined below reduces this correlation, the correlation remains substantial (r = −0.78) between the averaged values of νe and κ of different data groups. The LFS, QI shift and second-order Doppler shift all depend on the speed of the 2S atoms, either indirectly through the interaction time or directly. This results in non-zero Doppler slopes if not corrected for. In particular, the LFS, on average, would lead to κ ≈ −5 Hz (m s−1)−1 and it is only by accounting for it that the experimentally determined values of κ are, on average, compatible with zero.

The \(\chi _\rmred^2\) of the Doppler shift extrapolation (k = 14) is close to 1 (\(\chi _\rmred^2=1.04(2)\) on average; standard deviation over data groups in parentheses), showing that the data are well described by a linear model and technical noise is small compared with shot noise. This contrasts with the excess noise observed in the line shape fits, as discussed above. We attribute this to the different timescales involved: the different velocity groups are recorded for about 100 μs and within 2,560 μs of each other, whereas the signal at each detuning is accumulated for 1 s before moving to the next detuning. That is, the Doppler shift extrapolation is mainly susceptible to technical noise on timescales of 100 μs, whereas the signal at different detunings is susceptible to technical noise on timescales of about 1 s, which is, for example, the timescale expected for nozzle temperature fluctuations.

Next we find the weighted mean of νe from the two detectors for each line scan (except when no data from the bottom detector are available, in which case data from the top detector are used), taking into account experimentally determined correlations (r = 0.36(15) on average). We attribute these correlations, which tend to increase with spectroscopy laser power and therefore the signal, again to the detuning-to-detuning fluctuations in the atomic flux that are common mode to both detectors (and the velocity groups). We then form the weighted mean of the detector-averaged νe for each freezing cycle in a given data group. The reduced chi-squared \(\chi _\rmred,\rmFC^2\) of this average is typically greater than 1 (\(\bar\chi _\rmred,\rmFC^2=1.44(23)\) on average), which we attribute again to fluctuations in the atomic flux. We account for this excess scatter by scaling the uncertainty of νe by the corresponding \(\sqrt\chi _\rmred,\rmFC^2\) if \(\chi _\rmred,\rmFC^2 > 1\). This procedure shifts the determined transition frequencies (by changing the weighting of the data) by less than 20 Hz, much smaller than the associated uncertainties. A weighted mean of the detector-averaged, uncertainty-scaled νe is formed for each data group and the remaining corrections are applied (Table 1 and Extended Data Table 4). Finally, the relevant data groups are (weighted) averaged to find the transition frequencies of the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions. Throughout the analysis, the weights of the averages are based only on the (scaled) statistical frequency uncertainty (including for the Doppler slope κ), with the (correlated) uncertainty of the corrections not included in the weights. The statistical weights w2S–6P of the data groups for the determination of the 2S–6P fine-structure centroid ν2S–6P are given in Extended Data Table 3.

The data analysis was blinded by adding a randomly chosen offset frequency to the transition frequencies. The offset frequency was only removed after all of the main systematic effects had been studied. Further small corrections, identified after the offset frequency was removed, resulted in a negligible shift of the determined transition frequencies of at most 10 Hz. The results of the data analysis (performed by L.M.) were confirmed by a second, independently implemented analysis (performed by V.W.).

Modelling of atomic beam and fluorescence line shape

The fluorescence line shape of the 2S–6P transition is modelled by a Monte Carlo simulation of the atomic beam as a set of atomic trajectories, the trajectories’ interaction with the 1S–2S preparation and 2S–6P spectroscopy lasers and their contribution to the fluorescence signal. The procedure is described in detail in Section 1.1 in the Supplementary Methods. Two complementary models describe the interaction with the spectroscopy laser, the QI model (see below and Section 1.2 in the Supplementary Methods) and the LFS model (see main text and Section 1.3 in the Supplementary Methods).

Speed distribution of atomic beam

We use the signal of the velocity groups as a time-of-flight measurement of the speed distribution of the atomic beam. To this end, we compare the experimental values of the line amplitudes A of the velocity groups to the values of A of line shapes simulated using a given speed distribution (see Section 1.1 in the Supplementary Methods). We find that the probability distribution of the speed v of atoms leaving the nozzle towards the 2S–6P spectroscopy region is well described by a modified Maxwell–Boltzmann flux distribution for a wide range of experimental parameters (see ref. 23 for details). The flux distribution is given by

$$p_\rmeff(v)=\mathcalNv^3e^{-\fracm_\rmHv^22k_\rmBT_\rmN}e^{-\fracv_\rmcut-\rmoffv},$$

(12)

in which \(\mathcalN\) is a normalization constant. The extra factor exp(−vcut-off/v) accounts for the depletion of slower atoms through collisions inside the nozzle, inside the beam and with the background gas60,61,62. A similar depletion has been observed in our 2S–4P measurement and other atomic hydrogen beams3,63.

Using the above comparison of experimental data with simulations, vcut-off is found to be 50 m s−1 on average. Extended Data Table 3 lists the average value and variation for each data group. A substantial part of the variation is because of the fact that vcut-off typically increases during a freezing cycle (see Fig. 6.1 of ref. 23). This is because the accumulation of frozen hydrogen decreases the diameter of the nozzle, causing an increase in the gas pressure and therefore collisions inside the nozzle. We take this variation into account when determining (the uncertainty of) the mean speeds of the velocity groups and the simulation corrections (see Section 1.1 in the Supplementary Methods and Extended Data Table 5).

QI shift

We simulate QI-distorted line shapes with a model combining optical Bloch equations with simulations of the spatial detection efficiency, averaged over a set of trajectories representing the atomic beam (see Sections 1.1 and 1.2 in the Supplementary Methods). The QI shift is here defined as the centre frequency of a line shape fit to the simulated line shapes (see Section 1.1 in the Supplementary Methods). The validity of this approach was demonstrated by the excellent agreement between the observed and simulated QI shifts in our previous measurement of the 2S–4P transition2, in which the shifts were more than sevenfold larger because of the smaller detection solid angle and larger linewidth22.

The simulated QI shifts, as a function of polarization angle θL, are found to be at most 7.1 kHz and −4.1 kHz for the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions at our highest spectroscopy laser power (used to give upper limits here and below), respectively. At the magic angle θL = 56.5°, the shifts reduce to at most −0.87(54) kHz and 0.45(27) kHz (including ±3° alignment uncertainty; again at the highest spectroscopy laser power). When we account for data taken at θL = 146.5° (see below) and at lower laser powers (with statistical weights as given in Extended Data Table 3), we obtain the overall simulated shifts (−0.25(36) kHz and 0.05(15) kHz) given in the main text. The cancellation inherent in the 2S–6P fine-structure centroid reduces the shift to at most −0.37 kHz at any polarization angle and to below 0.01 kHz at around θL = 56.5° (below the otherwise negligible ac-Stark shift; see Section 1.2 in the Supplementary Methods). Including all data results in the shift of −0.05(2) kHz given in the main text.

The magic angle θL = 56.5° used in the measurement was determined with simulations before the measurement began, whereas more refined simulations of the spatial detection efficiency (completed after the measurement and used for all simulation results given here) result in a magic angle of approximately 52°. Moreover, the magic angle also slightly shifts with laser power (by up to 2° for the powers used here; see Section 1.2 in the Supplementary Methods). However, the QI shifts are still strongly suppressed at the magic angle used, despite it being slightly different from the optimal value.

To test our QI model and simulations, a limited amount of data were taken at θL = 146.5° (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Table 3), that is, orthogonal to the magic polarization angle, which we compare with the data taken at θL = 56.5°. For the 2S–6P1/2 transition, the difference in Doppler-free transition frequency of νe(θL = 146.5°) − νe(θL = 56.5°) = −0.01(1.69) kHz is in excellent agreement with 0 after correcting for a differential QI shift of 3.44(92) kHz and a differential Doppler shift of −1.42(1.42) kHz. We may also compare the experimental and simulated line shape distortions at θL = 146.5°, in which the QI shift dominates over the LFS, by comparing the asymmetry of the experimental and simulated fit residuals (Extended Data Fig. 1). We find excellent agreement, especially at detunings larger than the linewidth, for which the line shape distortions from QI are largest.

For the 2S–6P3/2 transition, we find a moderate (2.3 standard deviations) tension with a difference of νe(θL = 146.5°) − νe(θL = 56.5°) = 4.08(1.77) kHz in the transition frequency, having corrected for a differential QI shift of −1.78(47) kHz. The removed differential Doppler shift is likewise significantly non-zero (−3.66(1.68) kHz). This correlation is consistent with, but not conclusive evidence for, the non-zero difference being caused by random errors affecting the Doppler shift extrapolation. This conclusion is also supported by the fact that there is no tension in the velocity-group-averaged resonance frequency, that is, assuming zero Doppler shift (see Fig. 6.9 of ref. 23). Furthermore, we find the line shape distortions at θL = 146.5° to be compatible with our QI simulations but incompatible with a QI shift of opposite sign and twice the magnitude as implied by the measured difference (Extended Data Fig. 1). We therefore conclude that the tension probably results from random errors in the determination of the resonance frequencies.

2S–6P fine-structure centroid, 6P fine-structure splitting and HFS corrections

The 2S–6P fine-structure centroid ν2S–6P is the transition frequency from the 2S HFS centroid to the 6P fine-structure centroid. It is determined from the two measured transition frequencies ν1/2 and ν3/2 for the transitions from the \(2\rmS_1/2^F=0\) level to the \(6\rmP_1/2^F=1\) level (2S–6P1/2 transition) and the \(6\rmP_3/2^F=1\) level (2S–6P3/2 transition), respectively, by first correcting ν1/2 and ν3/2 for the 2S and 6P HFS and then averaging the corrected ν1/2 and ν3/2 weighted by their fine-structure multiplicity ratio of 1:2 (equivalent to the ratio of the line strengths ∝μ2 of the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions, in which μ is the dipole moment) to find the 6P fine-structure centroid. This results in equation (7), with the HFS corrections included in ΔνHFS(ν2S–6P), as detailed below.

The hyperfine interaction splits the fine-structure levels 2S1/2, 6P1/2 and 6P3/2 into doublets64,65. The relevant HFS levels \(2\rmS_1/2^F=0\), \(6\rmP_1/2^F=1\) and \(6\rmP_3/2^F=1\) are shifted from the fine-structure levels by the HFS energies \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(2\rmS_1/2^F=0)\), \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_1/2^F=1)\) and \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_3/2^F=1)\), respectively (see Fig. 6.11 of ref. 23 for the relevant level scheme). The value of \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(2\rmS_1/2^F=0)\) and its uncertainty are obtained from a measurement66 of the 2S HFS splitting ΔνHFS(2S1/2) as

$$\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(2\rmS_1/2^F=0)=-(3/4)\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(2\rmS_1/2)=-\mathrm133,167,625.7(5.0)\,\rmHz.$$

(13)

\(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_1/2^F=1)\) and \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_3/2^F=1)\) can be calculated as detailed in refs. 64,65. They include small corrections from off-diagonal elements in the HFS Hamiltonian, which mix HFS levels with the same value of F but different values of J. Because only the F = 1 level of each HFS doublet is shifted by this effect, the centres of gravity of the HFS doublets are shifted by \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS^\rmo.\rmd.(6\rmP_1/2)\) and \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS^\rmo.\rmd.(6\rmP_3/2)\). Using the values for the 6P HFS splittings ΔνHFS(6P1/2), ΔνHFS(6P3/2) and the values for \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS^\rmo.\rmd.(6\rmP_1/2)\), \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS^\rmo.\rmd.(6\rmP_3/2)\) given in Table 1 of ref. 64 (see also equations (29) and (30) in ref. 65 and comments therein), we find

$$\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_1/2^F=1)=(1/4)\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_1/2)+\Delta \nu _\rmHFS^\rmo.\rmd.(6\rmP_1/2)=\mathrm547,798(6)\,\rmHz,$$

(14)

$$\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_3/2^F=1)=-(5/8)\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_3/2)+\Delta \nu _\rmHFS^\rmo.\rmd.(6\rmP_3/2)=-\mathrm547,460(6)\,\rmHz.$$

(15)

\(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_1/2^F=1)\) and \(\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_3/2^F=1)\) are assumed to be fully correlated.

The resulting HFS correction of the 2S–6P fine-structure centroid ν2S–6P is

$$\beginarrayl\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(\nu _2\rmS-6\rmP)\,=\,-(1/3)\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_1/2^F=1)\\ \,-(2/3)\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_3/2^F=1)+\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(2\rmS_1/2^F=0)\\ \,=\,-\mathrm132,985,250(10)\,\rmHz,\endarray$$

(16)

in which we rounded to the nearest 10 Hz, as done for all corrections.

SM predictions of transition frequencies and bound-state QED test

We find the SM prediction ν2S–6P,SM of the 2S–6P fine-structure centroid using

$$\nu _2\rmS-6\rmP,\rmSM=\frac(1/3)E_6,1,1/2+(2/3)E_6,1,3/2-E_2,0,1/2E_2,0,1/2-E_1,0,1/2\nu _1\rmS-2\rmS=\fracE(2\rmS-6\rmP)E(1\rmS-2\rmS)\nu _1\rmS-2\rmS,$$

(17)

in which EnlJ are the fine-structure level energies from equation (1) and ν1S–2S is the measured frequency of the 1S–2S hyperfine centroid18. This parametrization removes the explicit dependence of EnlJ on R∞. Using the muonic value of rp (ref. 15), we find the value of ν2S–6P,SM given in equation (10).

Extended Data Table 1 lists the contributions to ν2S–6P,SM. Along with the Dirac eigenvalue (\(cR_\infty f_nJ^\mathrmDirac\) of equation (1); equation (30) in ref. 1), we list the individual QED corrections (\(cR_\infty f_nlJ^\mathrmQED\) and \(cR_\infty \delta _l0(C_\mathrmNS/n^3)\,r_\rmp^2\) of equation (1); equations (32)–(64) in ref. 1), with the sum of the corrections corresponding to the Lamb shift \(\mathcalL\) (\(\mathcalL(nlJ)\) for a single fine-structure level; \(\mathcalL(2\rmS-6\rmP)=(1/3)\mathcalL(6,1,1/2)+(2/3)\mathcalL(6,1,3/2)-\mathcalL(2,0,1/2)\) for the 2S–6P fine-structure centroid). Extended Data Table 1 also gives the QED-only uncertainty, which we define as the uncertainty excluding contributions from rp, α, mp/me and ν1S–2S. All listed QED corrections scale as cR∞C/n3 in leading order for S-states, in which cR∞C is the corresponding leading-order QED correction to the 1S level. This includes the (leading order, ∝α2 × α2, with the first α2 factor absorbed in R∞ = α2mec/2h in equation (1)) nuclear size correction highlighted in equation (1), for which \(C=C_\rmNSr_\rmp^2\). Therefore, the corrections between different S-states are correlated, which is taken into account in the uncertainty of ν2S–6P,SM. Non-S-states have generally much smaller corrections (for example, the fractional corrections are 1.3 × 10−6 of the 2S binding energy but 4.4 × 10−9 of the 6P binding energy) and, in particular, their nuclear size corrections are at present negligible (at most 7 × 10−16 of the 6P binding energy). There is no correlation between the different QED corrections and we find the total QED-only uncertainty of 179 Hz by adding the uncertainties of the corrections in quadrature. Overall, E(2S–6P) and E(1S–2S) are highly correlated (r = 0.995 if only considering QED-only uncertainty).

The other dominant source of uncertainty for ν2S–6P,SM is the muonic value of rp, which contributes 138 Hz to the uncertainty of ν2S–6P,SM. Although the uncertainty of rp itself partly originates from QED corrections15, the QED predictions for the energy levels of hydrogen and muonic hydrogen are uncorrelated at the present level of accuracy1 and we therefore treat the QED-only uncertainty and the uncertainty from rp as uncorrelated. The uncertainty contributions from α (1.7 Hz), mp/me (0.1 mHz) and ν1S–2S (3 Hz) are negligible. In total, this results in an uncertainty of 226 Hz on ν2S–6P,SM.

It is instructive to find the sensitivity of a prediction νSM, derived in the same way as ν2S–6P,SM, to changes in C. Making use of the 1/n3 scaling of the QED corrections (and using the approximation EnlJ ≈ chR∞(−1/n2 + δl0C/n3), that is, ignoring all non-leading-order corrections to \(f_nJ^\rmDirac\) and all QED corrections except C), we find

$$\frac\rm\partial \rm\partial C\left(\frac\nu _\rmS\rmM(n,n^\prime ,\mathopn\limits^ \sim ,\mathopn\limits^ \sim ^\prime )cR_\infty \right)\approx \left(\frac\delta _l0n^3-\frac\delta _l^\prime 0n^\prime 3\right)-\left(\frac\delta _\mathopl\limits^ \sim 0\mathopn\limits^ \sim ^3-\frac\delta _\mathopl\limits^ \sim ^\prime 0\mathopn\limits^ \sim ^\prime 3\right)\frac1/n^2-1/n^\prime 21/\mathopn\limits^ \sim ^2-1/\mathopn\limits^ \sim ^\prime 2,$$

(18)

in which n′, l′ → n, l is the transition to be predicted (for example, 2S–6P transition for ν2S–6P,SM) and \(\tilden^\prime ,\,\tildel^\prime \to \tilden,\,\tildel\) is the measured transition used as input (for example, 1S–2S transition for ν2S–6P,SM). The sensitivity of ν2S–6P,SM is ∂(ν2S–6P,SM/cR∞)/∂C = 0.134. By contrast, using the 1S–3S transition instead of the 2S–6P transition leads to a 1.8-fold lower sensitivity (∂(νSM/cR∞)/∂C = 0.074) because the relative contribution of C to the 1S–3S transition frequency is approximately twice as large as for the 2S–6P transition frequency. Combined with its 1.5-fold smaller uncertainty, ν2S–6P therefore tests C with 2.7-fold higher precision than the 1S–3S measurement5. Because the nuclear size correction \(cR_\infty C_\mathrmNS\,r_\rmp^2/n^3\) scales as 1/n3 like the other bound-state QED corrections cR∞C/n3, comparing rp found from atomic hydrogen and from muonic hydrogen is a test of bound-state QED, as any missing or miscalculated terms in atomic hydrogen of the form cR∞C/n3 would lead to a discrepancy. Furthermore, the precision with which rp can be extracted from a given combination of measurements is therefore a direct measure of the precision of the implied QED test. Note that, because Extended Data Table 1 lists the corrections of ν2S–6P,SM, which are approximately −cR∞C/23, the sensitivity relative to the listed corrections is −8 × 0.134 = −1.072. For example, artificially removing the hadronic vacuum polarization shifts ν2S–6P,SM by −1.072 × 425.1 Hz = −0.46 kHz, or approximately one experimental σ of ν2S–6P.

We may also extract the 1S Lamb shift \(\mathcalL(1\rmS)\) by writing equation (1) as

$$E_nlJ=chR_\infty f_nJ^\mathrmDirac+\delta _0l\frach\mathcalL(1\rmS)n^3+h\delta \mathcalL(nlJ),$$

(19)

in which \(\mathcalL(1\rmS)\equiv \mathcalL(1,0,1/2)=cR_\infty (f_1,0,1/2^\mathrmQED+C_\mathrmNSr_\rmp^2)\) and \(\delta \mathcalL(nlJ)=\mathcalL(nlJ)\,-\) \(\delta _0l\mathcalL(1\rmS)/n^3\) is the state-specific Lamb shift. By combining equation (19) for the 2S–6P and 1S–2S transitions and using ν2S–6P and ν1S–2S as inputs, we find \(\mathcalL_\exp (1\rmS)=\mathrm8,172,744.13(14)_\rmQED(3.56)_\exp \,\rmkHz\,=\) \(\mathrm8,172,744.1(3.6)\,\rmkHz\). Terms proportional to state-specific Lamb shifts contribute 224 MHz to \(\mathcalL_\exp (1\rmS)\). The uncertainty is dominated by the uncertainty of ν2S–6P (‘exp’), with the QED uncertainty of the state-specific Lamb shifts (‘QED’) being much smaller and contributions from ν1S–2S (22 Hz) and physical constants (10 Hz from α; mp/me, rp, R∞ less than 0.1 Hz) negligible. As expected from the discussion above, \(\mathcalL_\exp (1\rmS)\) is 2.7-fold more precise than the next best determination using the 1S–3S measurement5.

The corresponding QED prediction of the 1S Lamb shift is found by combining equation (1) with the muonic value of rp, giving \(\mathcalL_\rmQED(1\rmS)\,=\)\(\mathrm8,172,744.1(1.3)_\rmQED(1.0)_\rmr_\rmp\,\rmkHz=\mathrm8,172,744.1(1.7)\,\rmkHz\). Its uncertainty is dominated by both QED uncertainty and the uncertainty of rp, whereas other sources are negligible (3 Hz from α; mp/me, R∞ less than 0.01 Hz). \(\mathcalL_\exp (1\rmS)\) and \(\mathcalL_\rmQED(1\rmS)\) are uncorrelated, as their respective QED uncertainties are uncorrelated1. They are in excellent agreement and test the 1S Lamb shift and thereby bound-state QED corrections to 0.5 ppm. Complementary tests of bound-state QED in strong electromagnetic fields with highly charged ions at present achieve a relative precision of 1 × 10−4 but can be more sensitive to terms of high order in (Zα) (Z is the nuclear charge number; omitted elsewhere here because Z = 1 for atomic hydrogen)47,67,68.

Finally, the QED prediction ΔνFS,QED(6P) for the 6P fine-structure splitting between the \(6\rmP_1/2^F=1\) and \(6\rmP_3/2^F=1\) levels is (using equations (14) and (15))

$$\beginarrayl\Delta \nu _\rmFS,\rmQED(6\rmP)\,=\,E_6,1,3/2/h-E_6,1,1/2/h+\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_3/2^F=1)\\ \,-\Delta \nu _\rmHFS(6\rmP_1/2^F=1)\\ \,=\,\mathrm405,164.51(1)\,\rmkHz.\endarray$$

(20)

The nuclear size corrections in ΔνFS,QED(6P) are of order α2 × α4 and α2 × α5 and amount to 70 mHz, as the leading-order correction term \(cR_\infty C_\mathrmNSr_\rmp^2\propto \alpha ^2\times \alpha ^2\) of equation (1) and corrections of order α2 × α3 only apply to S-states1.

dc-Stark shift

Static stray electric fields in the 2S–6P spectroscopy region can lead to a dc-Stark shift of the observed transition frequency. Here the dc-Stark shift Δνdc is well described as quadratic in strength E = |E| of the electric field E in all relevant experimental regimes, that is,

$$\Delta \nu _\rmdc=\beta _\rmdcE^2,$$

(21)

in which βdc is the applicable quadratic dc-Stark shift coefficient. We distinguish two experimentally relevant field strength regimes: the stray-field regime (E < 1 V m−1), which covers the range of stray electric fields present in the experiment, and the bias-field regime (E = 10–45 V m−1), which covers the range of applied bias fields used to determine the stray electric fields. Notably, although equation (21) is found to approximately hold in either regime, the coefficient βdc may differ, as is the case for the 2S–6P3/2 transition (Section 1.4 in the Supplementary Methods). The quadratic behaviour arises because the energy levels contributing to the net shift are well separated in energy from the perturbed level in either of our regimes. However, the shift of the involved levels between the regimes can lead to substantially different energy separations and thereby different values of βdc.

The Faraday cage surrounding the spectroscopy region (Fig. 2b) shields it from external electric fields, including those used to draw the photoelectrons to the channel electron multipliers (whose input surfaces are held at 270 V; see Section 4.6.2 of ref. 23). The colloidal graphite coating on all surfaces of the Faraday cage suppresses stray electric fields from the surfaces themselves (from charged oxide layers, contact potentials from dissimilar conductors or local changes in the work function) by, ideally, forming a uniform conductive layer with a uniform work function (see Section 4.6.1 of ref. 23). However, effects such as imperfect shielding of external fields, imperfect graphite coating or temperature gradients leading to thermoelectric voltages or gradients in the work function can prevent the complete suppression of stray fields.

To address this, we measure the stray electric field by applying voltages to the six electrodes forming the Faraday cage (meshes at the top and bottom and four equal-sized segments of the cylinder wall) and using the atoms themselves as field sensors (see Section 4.6.7 of ref. 23), similar to approaches in refs. 5,69. Equal and opposite bias voltages are applied to opposing electrodes to create a bias electric field \(\bfE=E_i\hat\bfi\) with strength |Ei| = 10–45 V m−1 along the given direction (i = x, y, z, as defined in Fig. 2b). By measuring the shifted 2S–6P transition frequency νe(Ei) from a fit to the fluorescence line shape of several line scans with opposite-polarity values of Ei and using the quadratic dependence νe(Ei) = βdc,i(Ei − ΔEi)2 + νe(Ei = 0 V m−1), we determine the stray electric field component ΔEi along the given direction. This measurement also yields experimental values of βdc,i at the bias field strengths for each transition. Extended Data Fig. 3 shows examples of such stray field measurements for both the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions, along with simulation results (see Section 1.4 in the Supplementary Methods). On average, each measurement includes eight line scans with non-zero bias field and there are 98 and 21 measurements for the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions, respectively. The stray electric field components determined during the three measurement runs are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4, in which we only include measurements using the 2S–6P1/2 transition because using the 2S–6P3/2 transition gives compatible, but substantially larger uncertainty, values of ΔEi. Overall, the stray electric field has a strength less than 1 V m−1 and predominantly points along the axis of the detector cylinder (the y-direction).

Using these stray field measurements, we estimate the dc-Stark shift correction and its uncertainty for the transition frequencies. The determination of the relevant quadratic dc-Stark shift coefficients in the stray-field regime by the use of experimentally verified simulations is described in Section 1.4 in the Supplementary Methods. The weighted mean and standard deviation of each stray electric field component ΔEi are determined over each of the three measurement runs, using the 2S–6P1/2 stray field measurements, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. We treat each measurement run separately to account for differences in the detector assembly (the meshes in the detector cylinder were replaced between run A and run B; see Section 4.6.1 of ref. 23) and the month-long breaks in between the runs. Furthermore, we opt to use the standard deviation of the stray field components to estimate the dc-Stark shift uncertainty because we believe at least part of the variation of the stray fields to be physical in origin (as opposed to unaccounted excess measurement scatter) but are not confident that the resulting variations in the dc-Stark shift will average out. With this, we find dc-Stark shifts Δνdc of 0.20(21) kHz and −0.02(6) kHz for the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions, respectively, in which the uncertainty is dominated by the stray electric fields in the first case and by coefficients in the second case, and shifts for both transitions mainly determined by the dominant stray electric field component along the y-direction. ν1/2 and ν3/2 have been corrected for the dc-Stark shift by subtracting the corresponding value. The Pearson correlation coefficient of the correction between the 2S–6P1/2 and 2S–6P3/2 transitions is found to be r = −0.30 by propagation of uncertainty.