Stonehenge, the Neolithic stone circle on Salisbury Plain in southern England, has captivated archaeologists, antiquarians and sightseers for centuries. In the twelfth century, cleric Henry of Huntingdon described the haunting assemblage as one of the great wonders of England, adding that no one knew who built it or why. Over the millennia, its building has been variously attributed to the Romans, the Vikings, the Saxons, druids — and even Merlin, King Arthur’s court magician who, by one medieval telling, used his wizardly powers to whisk the stones over the seas from Ireland.

The mystery of Stonehenge’s central stone unearthed

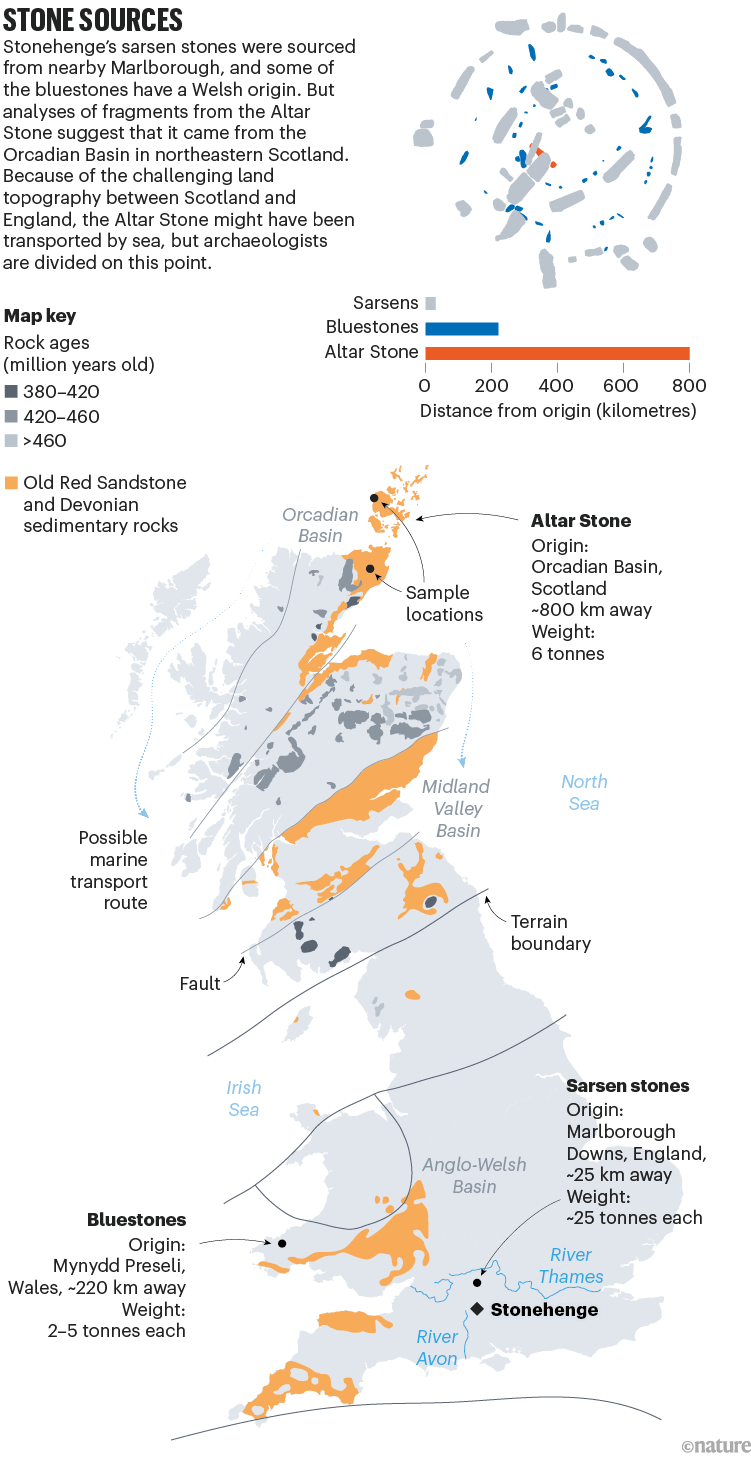

A geochemical analysis of the Altar Stone, a partially buried slab of sandstone at the centre of the stone circle, now suggests the truth might be an even livelier tale. In a study1 published in Nature on 14 August, scientists posit that some 4,500 years ago, Neolithic mariners might have transported this six-tonne monolith more than 800 kilometres by sea from the far north of Scotland — distinguishing its origin from the other stones, which came from England and Wales.

The discovery has thrilled archaeologists. “It’s a fantastic study with some big implications,” says Jim Leary, a field archaeologist at the University of York, UK. The findings increase researchers’ understanding of the henge’s builders, people of a Neolithic society that lived in Britain between about 4300 and 2000 bc.

At the centre of the circle is the Altar Stone, which lies recumbent under two other slabs.Credit: Gavin Hellier/robertharding/Getty

The culture flourished in the Orkney Islands in Scotland in the centuries before Stonehenge was completed, and archaeologists have been captivated by their art and pottery traditions, as well as their monuments they erected. “They built monuments that pointed to these wide connections,” says Leary. “It seems to me these later Neolithic people were master geologists, able to read stone and understand where it originated and the connections it symbolized.”

The Altar Stone is a greenish, partially buried piece of sandstone.Credit: Nick Pearce/Aberystwyth Univ.

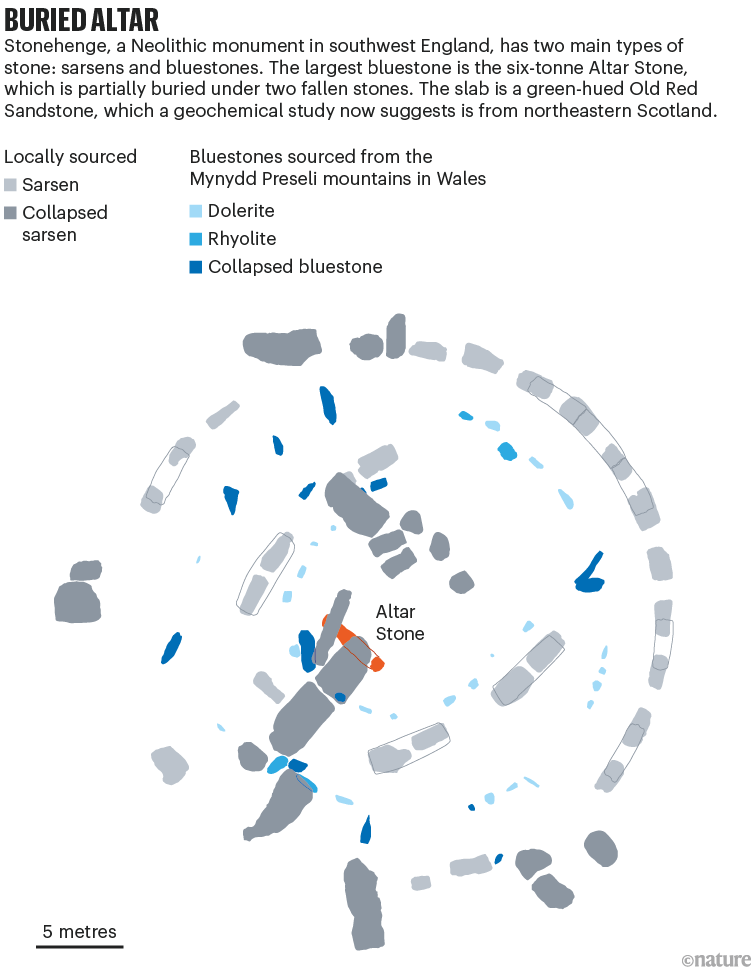

Stonehenge’s iconic slabs are divided into two groups. About 30 tall, upright sarsens make up the outer and inner circles, most pairs capped by shaped lintel stones. Studies have pinpointed2 the origin of the sarsens to the Marlborough Downs, about 25 kilometres away. The other blocks include about 80 bluestones, which analyses3–5 suggest came from the Mynydd Preseli mountains in western Wales.

The Altar Stone, a six-tonne chunk of sandstone that measures 5 metres by 1 metre, is the largest of the bluestones (see ‘Buried altar’). It was probably named by the seventeenth-century architect Inigo Jones, who commented on its recumbent appearance, although it is not known whether the block once stood upright. Previous research6 had suggested that the Altar Stone might also have come from Wales.

Source: Ref. 1.

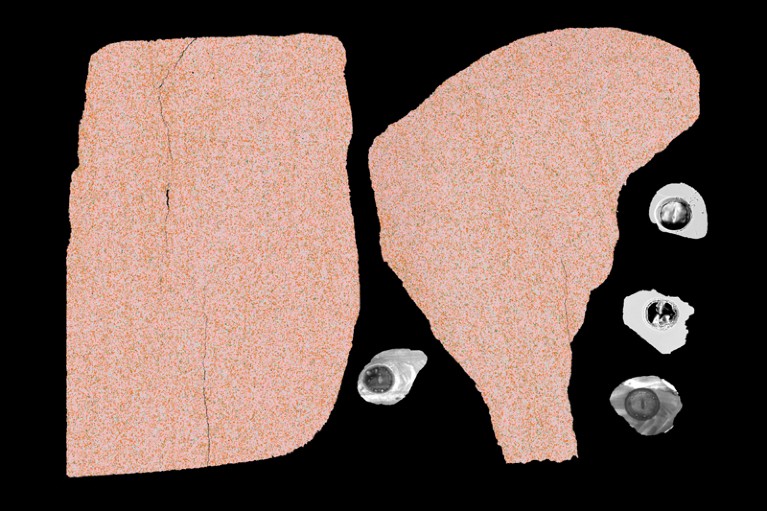

The latest study uses dating and chemical analysis of tiny zircon, rutile and apatite crystals from fragments of the Altar Stone to trace its source to the Old Red Sandstone formations in the Orcadian Basin in the northeast of Scotland and the Orkney Islands (see ‘Stone sources’). “It’s like finding a fingerprint,” says Anthony Clarke, a geochronologist at Curtin University in Perth, Australia, who led the study. “It was a perfect match for the Orcadian Basin and no match at all for anything in England or Wales.”

The fragments of the Altar Stone that were analysed, and the billion-year-old crystals (inset) that revealed the block’s origin.Credit: A. J. I. Clarke et al./Nature

The zircon, rutile and apatite crystals are nearly indestructible, says Clarke, and are essentially recycled over aeons as mountains are built and worn down. The researchers dated the crystals to one billion years ago. Their presence in the Altar Stone is a legacy of a time before the continents drifted into their present positions. What is now Scotland was then part of an ancient continental segment called the Laurentian Shield, which is in present-day eastern Canada. Old Red Sandstones found elsewhere in Britain won’t contain such ancient crystals, because the rest of Britain was part of a younger continental segment called East Avalonia. “The Altar Stone could only have come from Scotland,” says Clarke, who grew up in the Mynydd Preseli mountains, where the other bluestones are from.

Source: Ref. 1.

The Altar Stone is not the first artefact from Stonehenge with northern links. “A mace head found at Stonehenge has long been known to be made of Lewisian gneiss from the Hebrides” islands, says Mike Pitts, an independent archaeologist who wrote How to Build Stonehenge (2022).

Old Red Sandtone rocks on the Orkney Islands and in northeastern Scotland bear striking chemical resemblance to the Altar Stone.Credit: Geojuice/Alamy

How the stone was ferried to southern England from Scotland or the Orkney Islands is already a matter of lively debate. Geologists have ruled out the idea that glaciers might have transported it. “There is simply no evidence for it,” says Clarke. “This was brought here by human agency.”

Lead researcher Anthony Clarke as a one-year-old (left) at Stonehenge in the 1990s with his father, and with the lab equipment used to analyse rock samples (right).Credit: Curtin Univ.

Whether the people of Neolithic Britain moved it by land or by sea is an open question. The land between Scotland and Stonehenge is rugged, making for a difficult trek. “I can’t see them risking such a valuable cargo on such a hazardous journey,” says Pitts.

Leary thinks a sea journey is the most likely. “We seriously underestimate their abilities and technologies,” he says. “We’ve never found any of their boats, but we know they were able to transport cattle, sheep and goats by sea.”

Whatever the method, scientists agree that the transport of such an important stone would probably have been a spectacle, with people living along the route turning out to witness the event.

The Ring of Brodgar on Orkney is another stone circle built of sandstone; the monuments offer clues about the skills of Neolithic people.Credit: Getty

The discovery that the Altar Stone came from Scotland or Orkney isn’t the end of the matter. “We still need to narrow down exactly where it was obtained,” says study co-author Rob Ixer, a geologist at University College London who has spent decades tracing the sources of Stonehenge’s monoliths.

“Tracing these stones has always been like chasing a rabbit — it’s always bounding ahead of you. I think we’re going to have plenty more surprises as we go along.”