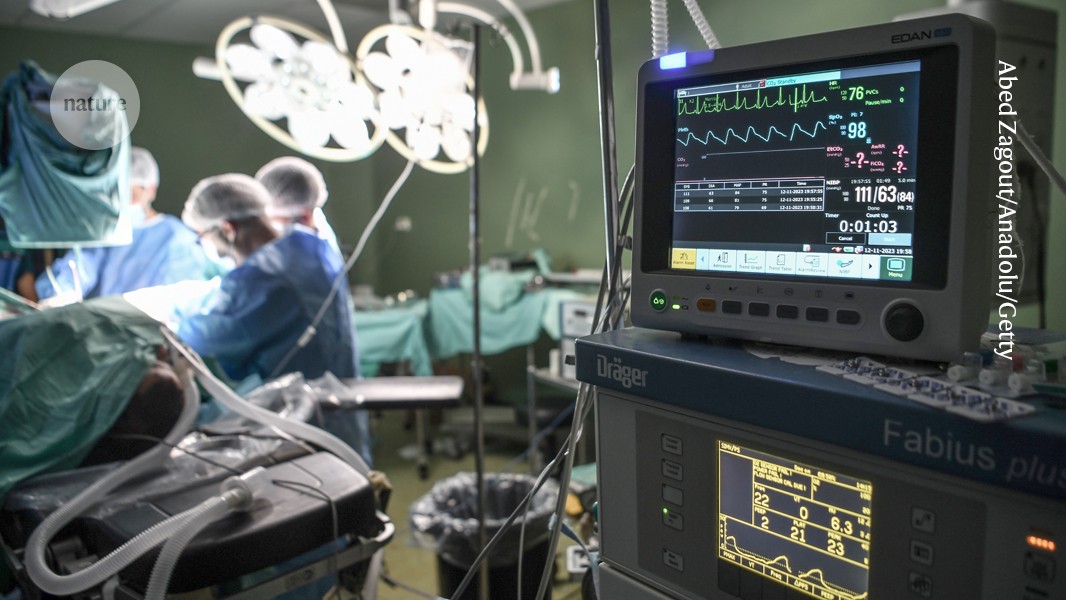

Unconsciousness induced by the widely used drug propofol is marked by characteristic changes in electrical activity. Credit: Abed Zagout/Anadolu/Getty

Scientists have identified a distinctive brain-wave pattern that marks the slide into unconsciousness during general anaesthesia. If the finding is confirmed, this pattern could help doctors to avoid sedating patients too deeply — or not deeply enough.

The data were collected from people about to have surgery. They show that as anaesthesia takes hold, the interplay between several brain areas falters. This shift could serve as a biomarker — a quantifiable biological measure — of loss of consciousness, the authors write today in Cell Reports Medicine1.

“This will finally provide the possibility [of] a translatable biomarker,” says co-author Ti-Fei Yuan, a neuroscientist at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China.

But, Yuan acknowledges, the study assesses the effects of only one anaesthetic and relies on a new technique to infer brain-wide signals from data recorded from outside the skull.

Going under

Scientists have long sought non-behavioural correlates of consciousness. Anaesthesiologists could use such signatures to fine-tune drug dosing and avoid the complications and side-effects of over- and under-sedation.

To seek such a marker, Yuan and his colleagues studied 31 people who received the widely used drug propofol as a general anaesthetic before surgery.

The consciousness wars: can scientists ever agree on how the mind works?

The authors placed 128 electrodes on each participant’s scalp to record the underlying neurons’ electrical activity from many positions. They then used emerging mathematical methods to isolate signals originating from nine brain regions previously implicated in mediating consciousness and examined connections between pairs of these regions. Among them were the parietal cortex, which is at the top of the brain about halfway between the forehead and the back of the skull; the occipital cortex, at the back of the head; and several small, deeper structures, such as one called the thalamus.

Before the propofol was administered, an oscillating brain wave called an alpha-band wave was highly synchronized between the parietal area and the thalamus. This correlation was a sign that these areas are in close communication in the awake brain. The researchers also saw signs of high connectivity between the parietal and occipital areas in the unsedated brain.