Experimental setup

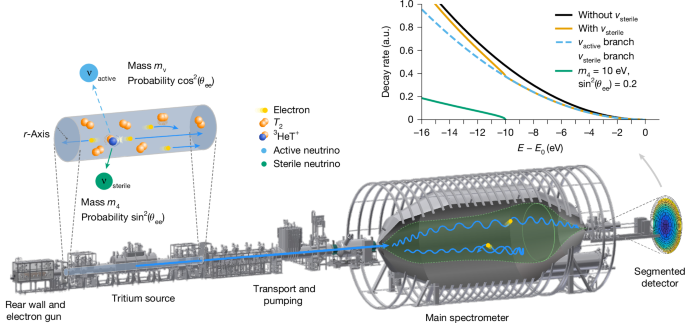

The KATRIN experiment measures the electron energy spectrum of tritium β-decay near the kinetic endpoint E0 ≈ 18.6 keV. The 70-m-long setup comprises a high-activity gaseous tritium source, a high-resolution spectrometer using the MAC-E-filter principle and a silicon p-i-n diode detector2,30.

Molecular tritium gas with high isotopic purity (up to 99%; ref. 48) is continuously injected into the middle of the WGTS, in which it streams freely to both sides. At the ends of the 10-m-long beam tube, more than 99% of the tritium gas is pumped out using differential pumping systems. With a throughput of up to 40 g day−1, an activity close to 100 GBq can be achieved49,50. The β-electrons are guided adiabatically by a 2.5 T magnetic field through the WGTS51. Before entering the spectrometer, they traverse two chicanes, in which the residual tritium flow is reduced by more than 12 orders of magnitude through differential52 and cryogenic pumping53. The β-electrons flowing in the upstream direction of the beamline reach the gold-plated rear wall, where they are absorbed. Besides separating the WGTS from the rear part of the KATRIN experiment that houses calibration tools, the rear wall also controls the source potential by a tunable voltage of \(\mathcalO\) (100 mV).

Electrons guided towards the detector are subjected to energy filtering by two spectrometers. A smaller pre-spectrometer first rejects low-energy β-particles. The precise energy selection with \(\mathcalO\) (1 eV) resolution is then performed by the 23-m-long and 10-m-wide main spectrometer. In both spectrometers, only electrons with a kinetic energy above the threshold energy qU are transmitted (high-pass filter). The electron momenta \(\bfp=\bfp_\perp +\bfp_\parallel \) are collimated adiabatically such that the transverse momentum is reduced to a minimum towards the axial filter direction by gradually decreasing the magnetic field towards the so-called analysing plane. In the main spectrometer, the magnetic field is reduced by four orders of magnitude to Bana ≲ 6.3 × 10−4 T. Behind the main spectrometer exit, the magnetic field is increased to its maximum value of Bmax = 4.2 T, resulting in a maximum acceptance angle of \(\theta _\max =\arcsin (\sqrtB_\rmS/B_\max )\approx 51^^\circ \), where θ is the initial pitch angle of the electron. The filtered electrons are counted by the FPD, which is a silicon p-i-n diode segmented into 148 pixels (ref. 40). This detector is regularly calibrated with a 241Am source to ensure stable performance. Its efficiency is about 95%, with only small variations between pixels that remain constant over time. Effects that do not depend on the retarding potential are accounted for by the free normalization combined fit across groups or patches of pixels54.

Background electrons are indistinguishable from tritium β-decay electrons and thus contribute to the overall count rate at the detector. There are different sources and mechanisms that generate the background events. The majority originates from the spectrometer section of the experiment. Secondary electrons are created by cosmic muons and ambient gamma radiation on the inner spectrometer surface55,56 but are mitigated by magnetic shielding and a wire electrode system30. The decay of 219Rn and 220Rn inside the main spectrometer volume is reduced by cryogenic copper baffles that are installed in the pumping ducts of the main spectrometer57. Another source of background is electrons from radioactive decays produced in the low-magnetic-field part of the spectrometer58. These primary electrons can be trapped magnetically, ionizing residual-gas molecules and producing secondary electrons that are correlated in time, leading to a background component with a non-Poisson distribution. The dominating part of the background stems from the ionization of neutral atoms in highly excited states, which enter the main spectrometer volume in sputtering processes (decay of residual 210Pb) at the inner surface of the spectrometer. The low-energy electrons emitted in this process are accelerated to signal-electron energies and guided to the detector. The magnitude of this background component scales with the flux tube volume in the re-acceleration part of the main spectrometer. A re-configuration of the electromagnetic fields in the main spectrometer, called the SAP setting, reduces the background by a factor of 2 by shifting the plane of minimal magnetic field from the nominal position in the centre of the spectrometer towards the detector while compressing the flux tube at the same time42,59. After successful tests, this configuration was set as the new standard (see the next section). There is also the possibility of a Penning trap being formed between the pre- and main spectrometer. The stored particles can increase the background rate. To counter this effect, a conductive wire is inserted between scan steps into the beam tube to remove the stored particles41. Because the duration of the scan steps differs, this creates a scan-time-dependent background. Reducing the time between particle removal events and lowering the pre-spectrometer potential enabled a full mitigation of the scan-step-duration-dependent background starting with the KNM5 measurement period. Moreover, the transmission and detection probabilities of background electrons may slightly depend on the retarding-potential setting, potentially causing a retarding-potential-dependent background. This effect is addressed in the analysis through an additional slope component, constrained by dedicated background measurements31.

KNM12345 dataset

The data collected by KATRIN is organized into distinct measurement periods, referred to as KATRIN Neutrino Measurement (KNM) campaigns. The integral β-spectrum is measured through a sequence of defined retarding-energy set points, which we refer to as a scan. Each dataset comprises several hundred β-spectrum scans, with individual scan durations ranging from 125 min to 195 min. The measurement time distribution (MTD), shown in Extended Data Fig. 1 (bottom), determines the time allocated for each qUi, optimized for maximizing sensitivity to a neutrino-mass signal, where the index i corresponds to different retarding energy settings. The energy interval typically spans E0 − 300 eV ≤ qUi ≤ E0 + 135 eV, following an increasing, decreasing or random sequence. The analysis presented in this work uses set points ranging from E0 − 40 eV to E0 + 135 eV and is based on the first five measurement campaigns (KNM1–KNM5), summarized in Extended Data Table 1. Extended Data Fig. 2 shows the electron energy spectra for each of the five individual campaigns.

The first measurement campaign of the KATRIN experiment, KNM1, started in April 2019 with a relatively low source-gas density of ρd = (1.08 ± 0.01) × 1021 m−2 compared with the design value of ρd = 5 × 1021 m−2. Here, ρ denotes the average density of the source gas, and d = 10 m is the length of the tritium source. The source was operated at a temperature of 30 K. The measurement in KNM1 lasted for 35 days, recording a total of about 2 million electrons. The sterile-neutrino analysis of this dataset was published in ref. 33.

After a maintenance break, the next campaign, KNM2, started in October of the same year and lasted for 45 days, only 10 days longer than KNM1. However, more than double the number of electrons was measured because of the increased source-gas density. The density was raised to ρd = (4.20 ± 0.04) × 1021 m−2, which corresponds to 84% of the design value. Although the background rate was reduced from 0.29 count per second (cps) in KNM1 to 0.22 cps, it was still above the anticipated design value of 0.01 cps (ref. 2). The sterile-neutrino analysis of this dataset, in combination with KNM1, was published in ref. 32.

To further reduce the background rate, a new electromagnetic-field configuration42 was tested in the next campaign, starting in June 2020. KNM3 was split into two parts to validate the new shifted-analysing-plane (SAP) setting in contrast to the nominal (NAP) setting. Before the start of the measurement, the source temperature was increased to 79 K. This allowed the co-circulation of gaseous krypton 83mKr with the tritium gas to perform simultaneous calibration measurements and β-scans60,61. In the first part of KNM3, KNM3-SAP, the β-spectrum was measured in the SAP setting for 14 days, and the background was subsequently reduced to 0.12 cps. Although the SAP setting reduced the background almost by a factor of 2, the increased inhomogeneities in the magnetic and electric fields require the segmentation of the detector analysis into 14 patches with 14 individual models59. In KNM3-NAP, it was demonstrated that switching between both settings works, and the background rate increased to 0.22 cps, as expected. The second part also lasted 14 days, and about 2.5 million electrons were measured in all of KNM3.

Before launching a new measurement campaign, a target source-gas density of ρd = 3.8 × 1021 m−2 was chosen to keep the same experimental conditions for future measurements. With the start of KNM4 in September 2020, one of the challenges was to reduce the background caused by charged particles accumulated in the Penning trap between the main and pre-spectrometer. The accumulation was time dependent, as the trap was emptied after each qUi. To reduce this background, the run durations were shortened to empty the trap more often. Finally, the Penning-trap effect was eliminated by lowering the pre-spectrometer voltage. Furthermore, the MTD was optimized during the campaign to increase the neutrino-mass sensitivity. This sequence defines the split into the first part, KNM4-NOM, and the second part, with an optimized MTD, KNM4-OPT. In all of KNM4, more than 10 million electrons were recorded in 79 measurement days.

The final dataset used in this analysis is KNM5, which started in April 2021. It contains more than 16 million electrons recorded in 72 measurement days. Before the start of the measurement, the rear wall was cleaned of its residual tritium with ozone. This step was necessary to address the accumulation of tritium on the rear wall, which produced an additional spectrum on top of the tritium β-spectrum, introducing new systematic uncertainties31.

Model description

General model

The KATRIN experiment measures the neutrino mass by analysing the distortions near the endpoint of the tritium β-decay spectrum. The model used for this analysis is described in the main text and follows the formalism outlined in equations (2) and (3). It includes the theoretical β-spectrum, the experimental response function and parameters such as the active-neutrino mass squared \(m_\rm\nu ^2\), sterile-neutrino mass squared \(m_4^2\) and the mixing parameter sin2(θee). The simulated imprint of a fourth mass eigenstate, with a mass of 10 eV and mixing of 0.05, is shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. To address the computational challenge posed by 1,609 data points requiring \(\mathcalO(1^3)\) evaluations of \(R_\rmmodel(A_\rmS,E_,m_\rm\nu ^2,m_4^2,\theta _\rmee,qU_i)\) per minimization step, an optimized direct-model calculation62 and a neural-network-based fast model prediction63 were used, as detailed in sections ‘The KaFit analysis framework’ and ‘The Netrium analysis framework’, respectively.

The KaFit analysis framework

KaFit (KATRIN Fitter) is a C++-based fitting tool developed for the KATRIN data analysis. It is part of KASPER—the KATRIN Analysis and Simulations Package64. KaFit uses the MIGRAD algorithm from the MINUIT numerical minimization library65 to fit KATRIN data. The fit minimizes the likelihood function −2log(L) in equation (4) with respect to parameters of interest such as the squared active-neutrino mass \(m_\rm\nu ^2\), \(m_4^2\), sin2(θee) and nuisance parameters Θ (ref. 62).

Model evaluation is done by the Source Spectrum Calculation (SSC) module, which returns the predicted electron counts for a given set of input parameters. Within SSC, the integrated β-decay spectrum is calculated by numerically integrating the differential spectrum after convolving it with the experimental response function, as in equation (3). Using the measurement times and the experimental parameters, the SSC module computes the prediction for the number of counts for each retarding energy qUi.

KaFit computes the negative logarithm of likelihood using the experimental and model electron counts. Twice the negative log-likelihood is referred to as χ2 in equation (4). KaFit minimizes the χ2 and returns the best-fit parameters and the corresponding \(\chi _\min ^2\). A typical minimization requires \(\mathcalO(1^4)\) evaluations of the χ2 function. For computational efficiency, KaFit and SSC make use of multiprocessor computing. The recalculation of all components of the spectrum model at each minimization step is avoided through caching, thereby reducing the overall minimization time by a factor of approximately \(\mathcalO(1^3)\). Moreover, caching the response function f(E, qUi) (equation (3)) and reusing it across systematic studies further reduces redundant calculations, enhancing the overall efficiency. KaFit has been optimized to enhance the computational speed for sterile-neutrino analysis while maintaining sufficient precision for physics searches within the current statistical and systematic budget.

The Netrium analysis framework

In the second approach to perform the analysis, a software framework called Netrium63 is used. In this case, the KATRIN physics model is approximated in a fast and highly accurate way using a neural network. It can predict the model spectrum \(R_\rmmodel(A_\rmS,E_,m_\rm\nu ^2,m_4^2,\theta _\rmee,qU_i)\) (equation (3)) for all main input parameters and improves the computational speed by about three orders of magnitude with respect to the numerical-model calculation. The neural network features an input and an output layer with two fully connected hidden layers in between. During the training process, \(\mathcalO(1^6)\) sample spectra, calculated using the analytical model, are used to optimize the weights of the neural network.

Comparison

Cross-validation between the two different analysis approaches to calculate the model is a key component of the blinding strategy of KATRIN (see the next section) and serves as quality assurance for the analysis. In previous sterile-neutrino searches with the KATRIN experiment32,33, the two described analysis approaches were benchmarked with the analysis software Simulation and Analysis with MATLAB for KATRIN (Samak)66, not used for the current analysis. It is based on the covariance matrix approach and designed to perform high-level analyses of tritium β-spectra measured by the KATRIN experiment. For this comparison, the results of the combined sterile analysis, based on data from the first five measurement campaigns, are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3. The active-neutrino mass is set to \(m_\rm\nu ^2=0\,\rmeV^2\). An excellent agreement is achieved for the exclusion contour and the best-fit parameter between the analyses conducted with KaFit and Netrium.

Blinding strategy and unblinding process

KATRIN applies a rigorous blinding scheme to minimize human bias and ensure the integrity of the analysis process. This approach also enforces robust software validation to avoid potential programming errors. The benchmark for validation is established by fixing the active squared neutrino mass to \(m_\rm\nu ^2=0\,\rmeV^2\) in all steps of the analysis.

The process began with the generation of twin Asimov datasets for each measurement campaign, in which all input values are set to their expected means67. These datasets were independently evaluated by two teams using the KaFit and Netrium software frameworks. Cross-validations confirmed an agreement within a few per cent of sin2(θee) between the results from the two teams. Only after this validation step was the combined analysis of all twin Asimov datasets performed. Once the validation using the Asimov data was completed, the real data were analysed on a campaign-by-campaign basis. Again, results from both teams were compared to ensure consistency. Only when the campaign-wise results demonstrated agreement did the analysis proceed to the final step, in which the complete, unblinded dataset was evaluated.

During the sterile-neutrino analysis of the KNM4 campaign, a closed contour with 99.98% CL was unexpectedly identified. This result was anomalous, given that all other campaigns, contributing the bulk of the statistics, consistently yielded open contours. The anomaly prompted a temporary suspension of the unblinding procedure and initiated a detailed technical investigation. The investigation uncovered a technical error in the combination of sub-campaigns within KNM4. Specifically, data from periods with different MTDs and effective endpoints cannot be directly stacked together. To address this, the dataset was divided into two distinct periods: KNM4-NOM and KNM4-OPT, reflecting the respective sub-campaign configurations. Apart from correcting the data-combination process, the analysis framework was improved with updated inputs and enhanced validation checks to prevent similar issues in the future. The identification of this error during the sterile-neutrino search also led to a re-evaluation of the neutrino-mass analysis, which was based on the same dataset. Detailed descriptions of all modifications and their impact can be found in ref. 31.

Results for individual campaigns

There are seven individual datasets (with KNM3 and KNM4 each split into two), corresponding to the first five measurement campaigns (KNM1–KNM5), which are described in detail in the section ‘KNM12345 dataset’. Each of the datasets can be used separately to search for a sterile neutrino. For campaigns measured in the NAP setting, the counts of all active pixels are summed up to one spectrum. By contrast, datasets in the SAP setting feature a patch-wise data structure (14 patches), in which, for each patch, nine pixels with similar electromagnetic fields are grouped together. Therefore, each dataset in the SAP setting contains 14 different spectra.

A sterile-neutrino search using the grid-scan method is applied to the seven individual datasets, whose exclusion contours at 95% CL are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. The differences in the accumulated signal statistics and their variations lead to different excluded regions in the sterile parameter space. The overall shape of the exclusion contours is very similar for all of the campaigns. The KNM4-NOM campaign enables the exclusion of a more extensive region of the sterile-neutrino parameter space associated with high sterile-neutrino masses; for low sterile-neutrino masses, the KNM5 campaign dominates.

Results for combined campaigns

Across the seven campaigns, a total of 68,237 scan steps were recorded, collecting approximately 36 million counts within the analysis window. As described in the section ‘KNM12345 dataset’, data were grouped primarily into seven sets according to the experimental conditions and FPD pixel configurations. Within each dataset, electrons collected at a particular retarding potential were summed over all the scans. This is possible given the ppm-level (10−6) high-voltage reproducibility of the main spectrometer68. For each of the NAP datasets (KNM1, KNM2 and KNM3-NAP), the counts from all the pixels were summed up to obtain datasets that feature counts per retarding potential. For the SAP datasets (KNM3-SAP, KNM4-NOM, KNM-OPT and KNM5), the detector pixels were grouped into 14 ring-like detector patches of nine pixels each, to account for variations in the electric potential and magnetic fields across the analysing plane42. Pixel grouping was determined based on transmission similarity. For each of the SAP datasets, counts per patch per retarding potential were obtained by summing over all scans and grouping pixels. These so-called merged datasets, containing 1,609 data points, were used in the sterile-neutrino analysis.

The combined data were analysed using the following definition of χ2:

$$\beginarrayl\chi ^2(\rm\theta )\,=\,-\,2lnL(\rm\theta )\\ \,\,\,\,=\,-\,2ln\mathop\prod \limits_i=0^If\left(\beginarraylN_\rmobs,i\,| \\ N_\rmtheo(qU_i,\rm\theta )\endarray\right)\\ \,\,\,\,=\,-\,2\,\mathop\sum \limits_i=0^Iln\left(f\left(\beginarraylN_\rmobs,i\,| \\ N_\rmtheo(qU_i,\rm\theta )\endarray\right)\right),\endarray$$

(4)

where θ is the vector of fit parameters, I denotes the total number of data points or retarding energy setpoints qUi, Nobs,i is the observed count at the ith setpoint, Ntheo(qUi, θ) is the theoretically predicted count at the ith setpoint and \(f(N_\rmobs,\rmi| N_\rmtheo(qU_i,\rm\theta ))\) represents the likelihood function, modelled using a Poisson distribution. The θ parameter values were inferred by minimizing χ2(θ).

For the combined KNM1–KNM5 analysis, further merging of the datasets is not possible because of the significant differences in the experimental conditions in which they were measured. The combined χ2 function incorporates contributions from both Gaussian and Poissonian likelihoods. Negative log-likelihoods of Gaussian models (\(\chi _\rmG^2\)) were used for the NAP campaigns as the mean value of the counts summed over all pixels was large, allowing the counts to be modelled by a Gaussian distribution31. Negative log-likelihoods of Poissonian models (\(\chi _\rmP^2\)) were applied to the SAP campaigns, as the mean value of the counts summed over pixels in each patch was not large enough. The combined χ2 function is expressed as

$$\beginarrayl\chi _\rmcomb^2(\Theta )\,=\,\sum _k\in \mathcalI_\rmG\chi _\rmG,k^2\left(\beginarraylm_\rm\nu ^2,\,m_4^2,\,\sin ^2\theta _\rmee,\\ E_0k,\,\rmSig_k,\,\rmBg_k,\,\xi \endarray\right)\\ \,\,\,\,\,\,+\,\sum _l\in \mathcalI_\rmP\mathop\sum \limits_p=0^13\chi _\rmP,lp^2\left(\beginarraylm_\rm\nu ^2,\,m_4^2,\,\sin ^2\theta _\rmee,\\ E_0lp,\,\rmSig_lp,\,\rmBg_lp,\,\xi \endarray\right)\\ \,\,\,\,\,\,+\,(\widehat\xi -\xi )^\rmT\varSigma ^-1(\widehat\xi -\xi ).\endarray$$

(5)

In this formulation, Θ is the vector of the physics parameters and the nuisance parameters of all the campaigns. Sigk and Siglp correspond to AS in equation (3) and Bgi and Bgjp represent the energy-independent background rate \(R_\rmbg^\rmbase\). Correlations among nuisance parameters ξ were captured by the covariance matrix Σ, with the mean values \(\widehat\xi \) determined from systematic measurements. In equation (5), \(\mathcalI_\rmG=1,2,3\text-NAP\) represents the KNM-NAP campaigns modelled with Gaussian likelihoods, whereas \(\mathcalI_\rmP=\text3-SAP, 4-NOM, 4-OPT, 5\) corresponds to the KNM-SAP campaigns modelled with Poissonian likelihoods. The exclusion bounds in Extended Data Fig. 5 compare results from the first two campaigns (KNM1–KNM2) to all five campaigns (KNM1–KNM5). The analysis highlights how increased statistics significantly improve exclusion limits across all \(m_4^2\) values.

Systematic uncertainty

An accurate and detailed accounting of the systematic uncertainties is essential for obtaining robust estimates of \(m_4^2\) and sin2(θee) from the tritium β-spectrum. Several systematic effects arise within the KATRIN beamline, influencing the shape of the measured spectrum. The systematic effects and inputs considered for this analysis are the same as in the neutrino-mass analysis31 and are treated as nuisance parameters. The central values \(\widehat\xi \) and covariance Σ of the systematics parameters were determined from calibration measurements and simulations. To include these effects in the likelihood function (equation (4)), they are modelled as a multivariate normal distribution \(\mathcalN(\widehat\xi ,\varSigma )\). Subsequently, the likelihood function is multiplied by the normal distribution of each systematic effect. It decreases the likelihood function if the parameters deviate from their mean values \(\widehat\xi \).

To assess the impact of individual systematic uncertainties, a separate scan of the sterile parameter space is performed for each systematic effect, considering only the statistical uncertainty and the specific systematic uncertainty in each case. This is done on the simulated Asimov twin data with \(m_\rm\nu ^2=0\,\rmeV^2\). The impact of individual systematic uncertainties on the sensitivity contour is quite small. Therefore, to evaluate the influence of systematic uncertainties more quantitatively, a raster scan is performed. In this approach, for each fixed value of \(m_4^2\) in the parameter grid, the 1σ sensitivity on the mixing sin2(θee) is calculated independently. By performing a raster scan, the number of degrees of freedom is effectively reduced to one at each grid point. The contribution of each systematic effect to the total uncertainty is determined using \(\sigma _\rmsyst=\sqrt\sigma _\rmstat+\rmsyst^2-\sigma _\rmstat^2\). The raster scan results for the combined KNM1–KNM5 dataset are presented in Extended Data Fig. 6 for three values of \(m_4^2\) as well as for all values of \(m_4^2\) in Extended Data Fig. 7. We can see that the statistical uncertainty dominates over all systematic effects. Owing to increasing statistics at lower retarding energies, the ratio of statistical to systematic uncertainties depends on the value of \(m_4^2\). Source-related uncertainties dominate the overall systematic uncertainty. The largest impact stems from the uncertainty on the density of the molecular tritium gas in the source column. It is followed by the uncertainty of the energy-loss function, which describes the probability that electrons will lose a certain amount of energy when scattering with the molecules in the source. Depending on the value of \(m_4^2\), variations in the source potential and the scan-time-dependent background also significantly affect the overall systematic uncertainty. The uncertainty from the scan-step-duration-dependent background is the first contribution of a non-source-related systematic effect.

Final-state distribution systematics

One source of uncertainty affecting the shape of the β-electron spectrum in KATRIN arises from the final-state distribution (FSD) of molecular tritium. During the decay process, part of the available energy can excite the tritium molecule into rotational, vibrational (ro-vibrational) and electronic states, thereby reducing the energy transferred to the emitted electron. Consequently, the energy distribution of these states directly influences the differential β-decay spectrum used in the analysis.

In previous KATRIN campaigns, the systematic contribution of the FSD uncertainty was estimated by comparing two ab initio calculations—one from ref. 34 and an earlier version from ref. 69—leading to a rather conservative estimation. For the analysis presented here, the FSD-related uncertainty was re-evaluated following the procedure derived for the neutrino-mass analysis36, which allows the estimation of the impact of FSD on the total uncertainty by considering the details of the calculation of the final-states distribution, such as the validity of theoretical approximations and corrections, the uncertainty of experimental inputs and physical constants, and the convergence of the calculation itself.

The same FSDs used in the neutrino-mass analysis, generated by perturbing the nominal set of input parameters entering the calculation, were used to create the twin Asimov datasets of the null hypothesis (no sterile neutrinos). Each dataset was then fitted with Netrium, trained on a single nominal FSD, with different values of m4 and sin2(θee). By comparing the resulting sensitivity contours at the 95% CL (\(\Delta \chi _\rmcrit^2=5.99\)) with that from the nominal case, the impact of FSD uncertainties can be quantified.

This analysis was performed using the KNM5 campaign alone, due to differences between the models used to generate FSDs in different campaigns. Nonetheless, the result of this analysis, presented in Extended Data Fig. 8, demonstrates that the various FSD effects have a negligible impact on the sensitivity contours, justifying the use of the nominal FSD for fitting with sufficient accuracy.

Applicability of Wilks’ theorem

The contours and their associated confidence regions reported in earlier sections were based on the critical threshold values \(\Delta \chi _\rmcrit^2\) corresponding to a desired CL. The sterile-neutrino search uses the Δχ2 test statistic:

$$\Delta \chi ^2=\chi ^2(H_)-\chi ^2(H_1),$$

(6)

where H0 is the assumed truth for the sterile-neutrino mass and mixing angle \([m_4^2,\sin ^2(\theta _\rmee)]\), and H1 represents the global best-fit hypothesis based on the observations. According to Wilks’ theorem44, as H0 represents a special case of H1, Δχ2 will follow a chi-squared distribution with two degrees of freedom in the large sample limit. Wilks’ theorem thus provides the critical threshold value \(\Delta \chi _\rmcrit^2\) corresponding to a desired CL, which allows us to quickly determine whether H0 is compatible with H1. This simplifies the sterile-neutrino analysis by providing a critical threshold \(\Delta \chi _\rmcrit^2=5.99\), which corresponds to a 5% probability of obtaining such a deviation purely because of random fluctuations under the null hypothesis. Thus, Δχ2 > 5.99 indicates a sterile-neutrino signal at 95% CL.

If Wilks’ theorem were not applicable, the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the Δχ2 test statistic would need to be computed for multiple combinations of the sterile-neutrino mass and mixing angle \([m_4^2,\sin ^2(\theta _\rmee)]\) using Monte Carlo simulations, which would require several thousand times more computational effort. To ensure the applicability of Wilks’ theorem to the analysis, the CDF of Δχ2 is numerically validated by performing calculations using Monte Carlo simulations for two sets of parameters. In the first case, \([m_4^2=0,\sin ^2(\theta _\rmee)=0]\) corresponds to the null hypothesis, whereas in the second case \([m_4^2=55.66\,\rme\rmV^2,\sin ^2(\theta _\rme\rme)=0.013]\) represents the best fit for the combined KNM1–KNM5 dataset. The CDFs and \(\Delta \chi _\rmcrit^2\) values obtained through Monte Carlo simulations were compared with those predicted by Wilks’ theorem.

For each of the sterile-neutrino mass and mixing-angle pairs, \(\mathcalO(1^3)\) tritium β-decay spectra were generated by adding Poissonian fluctuations to the counts calculated using the model described in the section ‘General model’. For each spectrum, the grid-scan method described in the main text is used to find the best-fit point and to compute Δχ2 using equation (6). For the case with \(m_4^2=0\,\rmeV^2\) and sin2(θee) = 0, the numerically computed or empirical CDF closely follows the analytical CDF of the chi-squared distribution, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 9. Similarly, in the scenario with \(m_4^2=55.66\,\rmeV^2\) and sin2(θee) = 0.013, the empirical CDF also aligns closely with the analytical CDF. In both cases, the observed threshold values at the 95% CL are consistent with the theoretical expectation of Δχ2 = 5.99. Specifically, for \(m_4^2=0\,\rmeV^2\) and sin2(θee) = 0, the critical Δχ2 at 95% CL is 6.07 ± 0.17, and for \(m_4^2=55.66\,\rmeV^2\) and sin2(θee) = 0.013, it is 6.07 ± 0.20. The uncertainties on the threshold values are calculated using the bootstrapping method. The combination of the CDF and the threshold values confirms the applicability of Wilks’ theorem to the sterile-neutrino analysis described in the main text.

Results compared with expected sensitivity

Figure 3 shows that the sensitivity contour, derived from simulations, intersects with the exclusion contour, obtained from the KNM1–KNM5 experimental data. For \(\Delta m_41^2 < 30\,\rme\rmV^2\), the exclusion contour extends beyond the sensitivity contour, whereas at higher \(\Delta m_41^2\) values, the exclusion contour oscillates around the sensitivity contour.

From the methodology outlined in the previous section and the description of \(\mathcalO(1^3)\) fluctuated Asimov datasets generated under the null hypothesis in the context of Wilks’ theorem, grid scans were performed to compute 95% CL contours. These scans distinguish between open contours (where Δχ2 < 5.99) and closed contours in which Δχ2 ≥ 5.99 and the best-fit value would be distinguishable from the null hypothesis. The statistical band, encompassing the sensitivity contour obtained from Asimov simulations along with its 1σ and 2σ fluctuations, was subsequently reconstructed. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 10, the KNM1–KNM5 exclusion contour, derived from experimental data, falls within the 95% confidence region of the fluctuated simulated open contours.

This test confirms that the observed intersection between the sensitivity and exclusion contours is consistent with expected statistical fluctuations in the experimental data.

Analysis with a free neutrino mass

In the main text, a hierarchical scenario is assumed with m4 ≫ mν. Under this assumption, for the sterile-neutrino analysis, \(m_\rm\nu ^2\) is set to 0 eV2. However, for a small sterile-neutrino mass and large mixing, the active and sterile branches can become degenerate. A strong negative correlation between the active and sterile-neutrino mass for small \(m_4^2\le 30\,\rmeV^2\) was reported in Sec. VI C of ref. 32. Hence, for small sterile-neutrino masses, it is interesting to perform the analysis considering the active-neutrino mass as another free parameter.

In Extended Data Fig. 11a, the 95% CL exclusion contours for the combined KNM1–KNM5 dataset are presented with statistical and systematic uncertainties incorporated. Two cases are analysed: the hierarchical scenario with the active-neutrino mass fixed to 0 eV2 (scenario I, solid blue) and the scenario treating the squared active-neutrino mass \(m_\rm\nu ^2\) as an unconstrained nuisance parameter (scenario II, dashed orange). The overlaid colour map indicates the best-fit values of \(m_\rm\nu ^2\) across the parameter space in scenario II. For sterile-neutrino masses below 40 eV2, partial degeneracy between the active- and sterile-neutrino branches weakens the exclusion bounds in scenario II relative to scenario I, with negative best-fit \(m_\rm\nu ^2\) values highlighting the negative correlation. For larger sterile-neutrino masses, the exclusion contours of scenario II converge with those of scenario I as the correlation between the active- and sterile-neutrino masses decreases.

Apart from scenarios I and II, two additional scenarios were considered with specific restrictions on the squared active-neutrino mass. In scenario III, \(m_\rm\nu ^2\) is treated as a free parameter but penalized by a ±1 eV2 pull term centred around 0 eV2. In scenario IV, \(m_\rm\nu ^2\) is constrained by \(0\le m_\rm\nu ^2 < m_4^2\), known as the technical constraint, first proposed by ref. 45. In Extended Data Fig. 11b, the 95% CL exclusion contours for the combined KNM1–KNM5 dataset are presented, incorporating only the statistical uncertainties.

The technical constraint in scenario IV (yellow dashed line) is of interest as its contour follows that of scenario I for lower squared sterile-neutrino masses (<40 eV2) and that of scenario II for higher masses. Similar to Extended Data Fig. 11a, for only statistical uncertainties, the best-fit squared active-neutrino mass in scenario II is negative for sterile masses below 40 eV2. As the squared active-neutrino mass is restricted to positive values in scenario IV, the resulting best-fit value is 0 eV2, causing the contour of scenario IV to align with that of scenario I for low sterile-neutrino masses.

KATRIN final sensitivity forecast

A projected final sensitivity for the KATRIN experiment at 95% CL is estimated using a net measurement time of 1,000 days, following the same prescriptions as in ref. 32. The background rate is expected to be 130 mcps for 117 active pixels, and the systematic uncertainties are based on the design configuration2. The primary update from the design configuration is the background rate, reflecting the current value. Moreover, the statistical variation is calculated using \(\mathcalO(1^3)\) randomized tritium β-decay spectra with counts fluctuating according to a Poisson distribution. Sensitivity contours are calculated for each random dataset, and the 1σ and 2σ allowed regions that define the statistical fluctuations of the projected dataset are identified. A comparison with the exclusion contour from KATRIN for the first five measurement campaigns, see Extended Data Fig. 12, shows that for sterile masses \(\Delta m_41^2 < 2\,\rmeV^2\) the final sensitivity contour is surpassed but not beyond the 1σ statistical uncertainty band. For \(\Delta m_41^2 > 2\,\rmeV^2\), the sensitivity projection highlights the potential of KATRIN to probe the unexplored sterile-neutrino parameter space and to reach sensitivities of sin2(2θee) < 0.01. Given the observed difference between our current exclusion and the median sensitivity, future data may also yield less stringent limits due to statistical fluctuations. This is accounted for in our sensitivity projections, as shown by the 1σ and 2σ bands in Extended Data Fig. 12, which illustrate the expected range of statistical variation around the median.

The Taishan Antineutrino Observatory (TAO)70, a satellite experiment of the Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO)71, is primarily designed to precisely measure reactor antineutrino spectra but also sensitive to light sterile neutrinos, particularly at low values of \(\Delta m_41^2\). The Precision Reactor Oscillation and Spectrum Experiment II (PROSPECT-II)72, an upgraded version of the original PROSPECT detector73, aims to enhance sensitivity to eV-scale sterile-neutrino oscillations. Together with the KATRIN experiment, these projects enable the exploration of sterile-neutrino mixing across a wide range of mass-splitting scales, allowing the probing of sin2(2θee) ≲ 0.03 for \(\Delta m_41^2\lesssim \mathrm1,000\,\rmeV^2\), as shown in Extended Data Fig. 12.