The space race between the U.S. and China has been heating up for a while now, as both nations seek to position themselves to own the future. America has been carefully watching China’s on-orbit capabilities become more advanced, and at the same time, China is getting closer to landing people on the Moon again — before NASA’s Artemis program. Now, the Space Force is also realizing that China has ambitions a lot closer to home, so close that the U.S. hasn’t even tried to compete in this environment before. Welcome to the not-quite-space race.

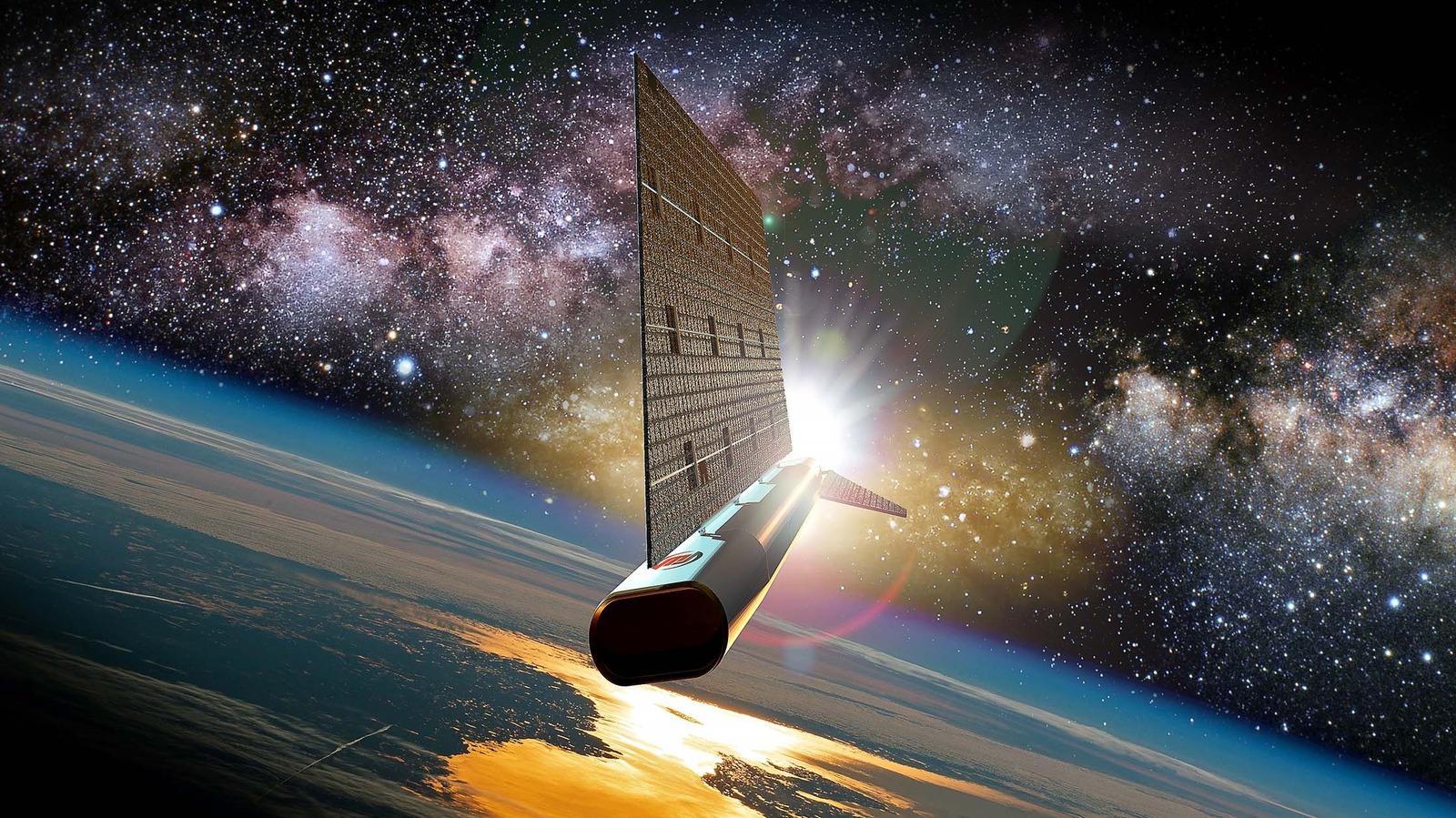

The area in question is called very low-Earth orbit (VLEO), which, as you might imagine, is even lower than low-Earth orbit (LEO), usually the nearest environment where spacecraft operate. VLEO covers anywhere from 55 to 280 miles above the Earth’s surface. This is where the atmosphere has gotten far too thin for conventional airplanes to fly, but is still just present enough to prevent it from being a vacuum. That trace amount of air means drag, which will slow down a satellite and eventually cause it to crash back to Earth. It also means that oxygen, a terribly corrosive gas that I can’t believe I have to breath every day, will degrade the orbiter over time.

Seems like a terrible place to fly anything! And so, for the last few decades, basically nobody has. Now China is asking everyone else to hold its beer, and Space Force is refusing.

Hybrid spaces

Part of this comes down to how the two countries actually think about air and space. Even the way I just wrote that, “air and space,” is a clue: the West tends to think of these as two separate categories, with a hard line between them. That means different considerations, technologies, regulations, and even military branches.

By contrast, the Chinese “see it as a continuum,” according to Space Force Chief Deputy Science Officer Dr. Gillian Bussey, via Via Satellite. “In the U.S., we say the Von Karman line, above that 100 kilometers you’re in space, below that in air, whereas I’m not sure our adversaries see it that way. They’re pursuing technologies that blend those two domains and operate seamlessly between them.”

China seems to be pursuing hybrid spaces like this as a possible way to slip through conventional defenses. Just this year, a wing-in-ground (WIG) effect plane or “ekranoplan” was spotted in China as the country resurrects an old design for a vehicle that’s somewhere between a plane and a boat. It’s not a coincidence that America’s current arsenal doesn’t have anything specifically designed to deal with something like that.

The U.S., of course, won’t want to be left in the dust here. Just like DARPA is exploring its own ekranoplan designs now, it’s also exploring VLEO. And it turns out, there’s a number of good reasons to fly a lot closer to home.

Drag is good, actually

Conventionally, we think of drag as bad for satellites: part of their whole thing is that they can just fly friction-free forever, without then need for thrust (except to adjust trajectory). So VLEO, with its pesky trace amounts of atmosphere, was viewed as a bad thing. But there’s another way to look at drag: you can use it for both maneuvering and propulsion. Atmosphere is good, actually.

Planes operate by manipulating airflow over their wings, so a craft in VLEO could do something similar, giving it much more agility than a satellite. Also, right now Space Force and DARPA are funding projects from Rocket Lab and Redwire, respectively, specifically looking for ways to use ambient air as a propellant. If that technology gets worked out, then these craft won’t have to carry much in the way of on-board fuel, which saves weight and thus makes launches cheaper.

What you can do when you’re in very low orbit

New domains open up new opportunities. Being closer to the ground means stronger signal strength and more detailed photography, two things the military tends to care about a lot. More spaces also provide more redundancy; just in case the Chinese figure out how to knock out satellites, VLEO craft may keep on operating.

Interestingly, VLEO craft fail better, too. The dreaded Kessler Effect describes a scenario where, if a collision in space leads to enough scattered debris, that shrapnel will keep expanding and collide with more satellites, which will create more shrapnel which will collide with more satellites, until maybe every satellite is taken out. By contrast, since VLEO’s drag will quickly pull any non-propelled objects to Earth, a collision in that environment cannot create this effect.

Bussey herself has another way of thinking about VLEO’s potential: “It’s not really entirely clear exactly how we would use VLEO, or exactly what the threat is expected to be there.” In other words, this just isn’t a domain that anybody’s really sure about. But if the Chinese start going for it, expect that we will, too. After that, we might need to start rethinking what we mean by “air” and “space.”