You have full access to this article via your institution.

By working together, research institutions and science sleuths can boost science integrity.Credit: Getty

For years, scientific sleuths have been catching and drawing attention to instances of falsification, fabrication and plagiarism in science. But a recent survey of sleuths and research-integrity personnel shows that sleuths — some of whom also work full-time as scientists — have different views on how to deal with integrity concerns compared with research-integrity officers at institutions such as publishers and universities.

Differences of opinion are nothing new in research. But the survey of some 80 people by Dorothy Bishop at the University of Oxford, UK, also highlights a need for trust between the communities surveyed, not least because, as Bishop writes, all involved want to strengthen research integrity (D. V. M. Bishop Preprint at Zenodo https://doi.org/px4d; 2025). They must find a way to work better together.

How to tackle research misconduct: survey finds stark disagreement

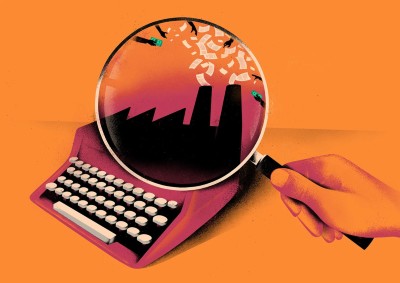

Sleuths are busy people. The pressure on many researchers to publish quickly to advance or sustain their careers is fuelling unethical research practices and, in some cases, outright fraud. In their pursuit of integrity, some sleuths do go beyond accepted institutional processes. Earlier this month, for example, a group of sleuths from various countries gathered outside the offices of a known paper mill — a fraudulent research-publishing business — in Krakow, Poland, hoping to confront the owner. But a potentially much bigger problem is the fact that, overall, sleuths and research-integrity officers are not on the same page when it comes to the perceived extent of the problem — and the threat the issue poses to science itself.

The survey found that sleuths were much more likely than institutional integrity officers to agree with the statement that “serious research misconduct is already common enough to pose a major threat to the research literature”. Some sleuths whom Nature contacted for this Editorial say that they want to see faster retractions — or at least faster publication of expressions of concern — when issues are raised in relation to published papers. But if an individual or an organization is suspected of wrongdoing, evidence needs to be collected and assessed. All sides must then be given an opportunity to explain or defend their position before an outcome is decided. This cannot be rushed.

Authorship for sale: Nature investigates how paper mills work

Sleuths and integrity officers agree that journals and universities need to find ways to share information when handling integrity concerns (as Nature has also argued). But the sleuths are more likely to argue that research-integrity processes should be independent of institutions to minimize conflicts of interest. Some go further, saying that such processes should have independent regulatory or legal force, similarly to the way misconduct is dealt with in medicine, for example. By contrast, the research-integrity staff at institutions are more likely to favour existing self-regulatory practices, whereby cases are dealt with internally by an institution, albeit perhaps according to guidelines determined by a national body.

How, then, can the different communities move forwards? One idea would be for sleuths to form a collective to represent their interests. The plural ‘sleuths’ masks the fact that the work is mostly self-funded by individuals working in their own time. If sleuths could organize themselves in some way, that would establish regular channels of communication with other groups that have an interest in improving research, including governments. It would also open up the possibility of providing funding support for sleuths.

Retractions are part of science, but misconduct isn’t — lessons from a superconductivity lab

Establishing a degree of organization will be uncomfortable for those who prefer to work independently. Indeed, some sleuths say they are in opposition to the business and structures of science. However, working outside the academic system means that individual sleuths lack the resources that employers and other groups can provide to support their case. Calling out papers online for perceived faults also carries legal risks. A more collective approach could offer a protective layer, which would also be beneficial when sleuths’ work is misinterpreted or misrepresented by bad actors.

Science benefits from the time sleuths devote to spotting and flagging text generated by artificial intelligence, images edited using software, and dodgy statistics. At the same time, a core principle of scientific exchange is the right for a researcher, working in good faith, to be wrong.

Integrity officers and sleuths share a goal — to protect the integrity of science — while performing complementary functions. They need not agree on everything to be allies. Rather than seeing one another as rivals, they can work towards building a more trusting relationship in the interests of achieving their shared goal.