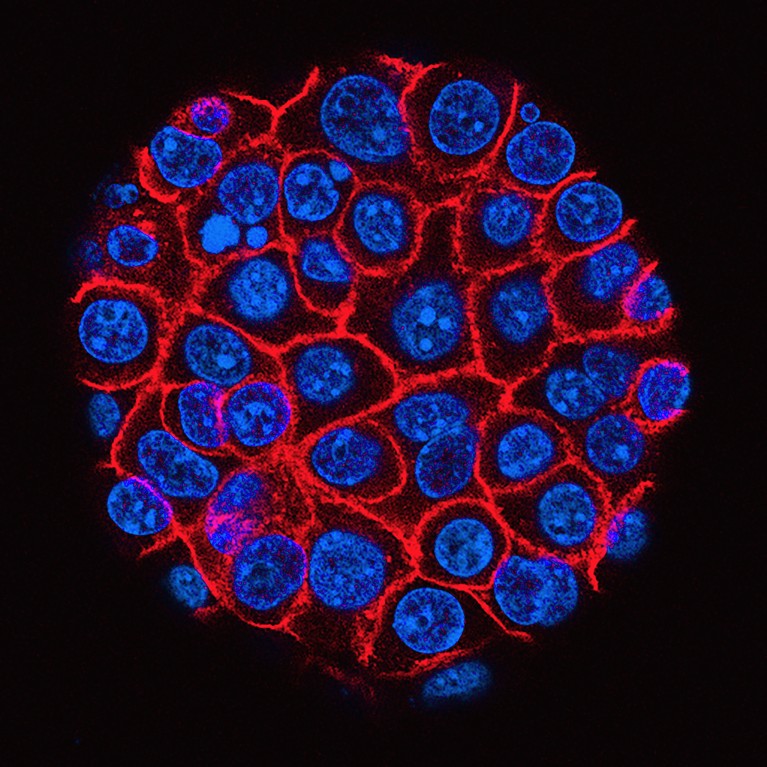

The growth of pancreatic cancer cells (blue) is often aggressive.Credit: USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center/National Cancer Institute/SPL

Decoding aggression

Pancreatic cancer is extremely aggressive. One reason for this is the dense physical barrier that surrounds the tumour, known as the stroma. This is composed of tumour cells, and a network of proteins and other cell types, such as fibroblasts. The stroma protects cancer cells from the body’s immune response and from drugs intended to treat the malignancy.

Nature Outlook: Pancreatic cancer

Stroma fibroblasts were known to secrete galectin-1 (Gal-1), a sugar-binding protein that helps cancer cells to grow. But an international team led by Pilar Navarro at the Institute of Biomedical Research of Barcelona, Spain, has now identified Gal-1 inside the nuclei of fibroblasts, in which it regulates the expression of several cancer-associated genes, including KRAS. Because Gal-1 fuels the production of KRAS protein inside fibroblasts, these cells stay activated, promoting tumour growth and spread.

The newly-discovered location of Gal-1 expands the focus of therapies that inhibit it. Researchers say that targeting Gal-1, both in and outside cells, is a promising strategy that might help to improve outcomes for people with pancreatic cancer. Therapies that can enter tumour-associated fibroblasts and block Gal-1 in the nucleus might help to reprogram the cells into a less aggressive and activated state, potentially diminishing their role in tumour development and aggression.

Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2424051122 (2025)

Encrypted proteins

The ‘dark genome’ — the 98% of a person’s genetic code that is not usually used to produce proteins — is now known to be used by some cells to produce short chains of amino acids known as cryptic peptides. Now, a team of researchers has identified hundreds of cryptic peptides that are specific to pancreatic tumours.

A team led by William Freed-Pastor at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and Tyler Jacks at the Koch Institute at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, used human tumour samples to produce pancreatic organoids — simplified 3D versions of the larger cancerous organ — and extracted the peptides from the surface of the cells. The team then attempted to find matches for these peptides in healthy tissues. It found roughly 500 cryptic peptides that are not produced by normal cells, and seem to be unique to pancreatic cancer.

To test the potential therapeutic utility of these peptides, the researchers tried to generate T cells against each of them. Engineered T cells specific to 12 of the peptides could destroy the organoids produced from pancreatic tumour cells. In a separate experiment, in which the organoids were implanted into mice, the same engineered T cells could not completely eradicate the tumour, but did slow its growth. In the future, cryptic peptides could be used to prompt specific T cells to attack a tumour. Efforts are now under way to develop therapeutics that target some of these peptides.

No safe level of alcohol

Drinking alcohol raises the risk of many cancers, but evidence linking it specifically to a risk of pancreatic cancer has been in short supply. Now, a large-scale analysis involving almost 2.5 million people across four continents reveals that alcohol consumption — even small amounts — can increase a person’s chance of developing the cancer.

Sabine Naudin at the Centre for Research in Epidemiology and Population Health, Villejuif, France, and colleagues pooled data from 30 large studies involving cancer-free participants in Asia, Australia, Europe and North America who self-reported their alcohol consumption through questionnaires. Over a 16-year follow-up period, on average, 10,067 people — or 0.4% of the study population — were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

To assess the level of risk, the team looked at the effect of steady increases in alcohol consumption. Each 10 gram per day increase (a little less than a 330-millilitre bottle of regular beer) in alcohol intake was associated with a 3% increase in pancreatic cancer risk, the team found, suggesting that any amount of alcohol can be risky. When the researchers measured alcohol consumption by volume, compared with weak intake (0.1–5.0 g per day), the risk became significant for women at one to two drinks per day (15–30 g per day), and two to four drinks for men (30–60 g per day). The researchers also found that the type of alcohol consumed influenced the risk. Spirits and beer were linked to increased risk, but wine was not associated with a significant change in risk. Location also seemed to make a difference. Participants from Europe, Australia and North America seemed to have a higher risk of developing the disease, but those from Asia did not, suggesting the role of specific drinking habits needs further study.

GLP-1 drugs — friend or foe?

Therapies such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, which mimic the natural hormone glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), lower blood sugar and reduce appetite. They are highly effective at treating people with type 2 diabetes and obesity. Some studies have suggested a link between GLP-1 drugs and pancreatitis — a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Three studies have now independently found, however, that not only do GLP-1 drugs not increase the risk of pancreatic cancer, but that their use is also associated with a reduction in risk.

In one study, Rachel Dankner at the Gertner Institute for Epidemiology and Health Policy Research in Ramat Gan, Israel, and colleagues examined electronic health records of more than 500,000 adults with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, around 30,000 of whom took GLP-1 drugs to manage the disease. The researchers found that people taking GLP-1 drugs were not at higher risk of pancreatic cancer than those prescribed insulin.

In the second study, Mark Ayoub at West Virginia University, Charleston, and colleagues found that cancer risk was lower among people in the United States who were receiving GLP-1 drugs (0.1%) compared with the control group (0.2%), after adjusting for factors such as age, alcohol use and family history of the disease. In the third study, Lindsey Wang at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio, and colleagues found that people taking GLP-1 drugs for type 2 diabetes were 59% less likely to develop pancreatic cancer than were people given insulin treatments. Their risk for 10 of 13 obesity-related cancers was also significantly lower.

JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2350408 (2024); Cancers 16, 1625 (2024); JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2421305 (2024)

A detailed map of immune response

Researchers have long suspected that the immune cells that surround tumours help to determine the fate of the cancer, but the mechanism is poorly understood. Now, a multicentre study has created a detailed map of the immune response in pancreatic cancer by using computational tools to analyse health data from 12 people with the disease, including immune cells from their tumours and blood samples.

The team found there were two classes of tumour: one filled with a type of white blood cell called a myeloid cell, and another dominated by the B and T cells that help the body to fight infections. In this second type of tumour, researchers also discovered that a T cell known as a killer T cell was very active, suggesting that it might participate in fighting the tumour. By contrast, the myeloid-cell-enriched tumours were replete with cells known as regulatory T cells that could suppress the body’s immune response against the tumour.

The team corroborated this finding using clinical data from a large international trial. People with myeloid-enriched tumours survived for a shorter time after diagnosis than did others, suggesting that targeting regulatory T cells or boosting B-cell responses might improve overall survival.

Nature Commun. 16, 1397 (2025)

Is pancreatic cancer really on the rise?

Several reports have pointed to an increase in pancreatic cancer cases in young people in the United States over the past five years, especially in young women. But the apparent rise might be overblown, suggest H. Gilbert Welch at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts and colleagues.

The researchers say that, given the lethality of the disease, if cases were truly increasing, then the number of deaths would also be rising. To test this, the team analysed 20 years’ worth of data for individuals aged 15–39 years found in the US Cancer Statistics database. They looked at cancer type and stage, and cross-checked this with mortality data from the US National Vital Statistics System.

The incidence of pancreatic cancer increased 1.6-fold (from 3.9 cases per million to 6.2 cases per million) during the study period in young men and 2.1-fold (from 3.3 to 6.9 cases per million) among young women. But mortality stayed stable at 2.5 deaths per million for men and 1.5 deaths per million for women. The researchers found that the increase was due to cases of a more indolent form, called neuroendocrine cancer, rather than of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Although these small neuroendocrine cancers have always been present, they are now detected more easily using computed-tomography scans. Advances in diagnostics might, therefore, be responsible for the apparent rise in pancreatic cancer cases.