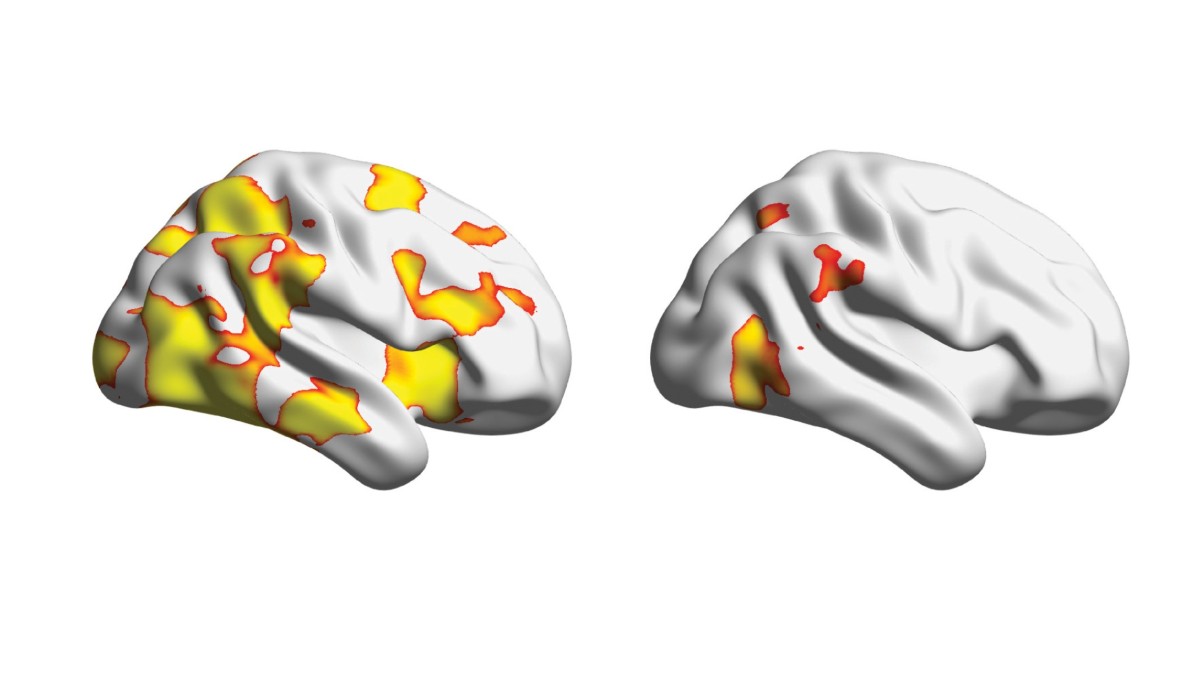

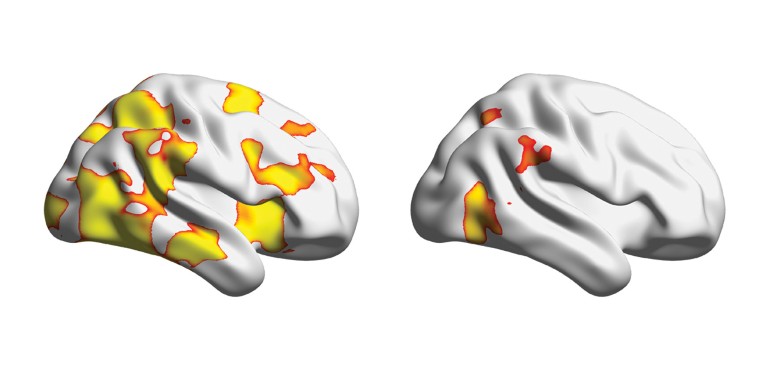

The brains of typically developing children (left) exhibit greater spatial stability than those of children with ADHD (right).Credit: Z. Ghao et al. Nature Commun. 16, 2346 (2025)

Quantifying shorter life expectancies

Adults diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have poorer education and employment outcomes than the rest of the population, and worse physical and mental health. There is also evidence suggesting that they are more likely to die prematurely as the result of adverse consequences of symptoms, such as alcohol and substance use, suicidal behaviours and overall worse health.

Nature Outlook: ADHD

A team led by Josh Stott at University College London used primary-care data to confirm that people with ADHD do indeed, on average, lead shorter lives than people without ADHD. The researchers compared records from 2000 to 2019 for about 30,000 adults (aged 18 or older) with ADHD diagnoses and 300,000 adults without one. They calculated an average reduction in life expectancy of 6.8 years for men diagnosed with ADHD and 8.6 years for women.

This is the first study to use mortality data to calculate the number of years of life lost as the result of ADHD. The researchers say that this reduced longevity is mainly due to modifiable risk factors, such as alcohol use and smoking, as well as insufficient support and treatment, both in terms of ADHD directly and any co-occurring physical and mental health conditions.

The researchers caution that the results might not generalize to the whole population with ADHD, because they looked only at people with diagnoses. Other research, they say, suggests that most adults with ADHD are undiagnosed.

Br. J. Psychiatry 226, 261–268 (2025)

How symptoms fluctuate over time

ADHD is usually viewed as a chronic condition, but some studies have estimated that around half of children with an ADHD diagnosis recover by the time they are adults. Evidence is growing, however, that ADHD typically doesn’t simply remit or persist, but rather fluctuates over time.

A 2022 study led by Margaret Sibley at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle analysed data from 558 participants and found that only 9.1% of people with childhood ADHD diagnoses recovered. Most (63.8%) experienced fluctuating symptoms, ranging from full-severity ADHD in some years to mild or no symptoms in others. The study also identified two other groups: people who consistently met diagnostic criteria, termed ‘stable persistence’ (10.8%); and people who experienced one shift, from full ADHD to subclinical but still-meaningful problems (15.6%), termed ‘stable partial remission’.

To investigate what might be driving the fluctuations, the team conducted a follow-up study including most (483) of the same participants. Participants were 8.5 years old, on average, at the start of the study and were assessed nine times over 16 years, reaching an average age of 25.1. The researchers compared symptoms over time with factors that might be associated with fluctuations, including co-occurring mental health conditions and environmental demands, such as work and educational responsibilities.

Participants in the fluctuating group experienced several periods of remission and recurrence (3.6, on average), with a difference of 6 to 7 symptoms between their best and worst periods (6 of a possible 18 ADHD symptoms are required for a childhood diagnosis). Remissions first occurred at around 12 years of age, with recurrences appearing in a few years.

Surprisingly, participants were more likely to experience remission when environmental demands were higher, indicating that more-demanding lives might help some people to manage symptoms better, possibly because of factors such as structure and motivation. The study cannot establish causality, however, so it is also possible that people were simply able to handle more responsibilities during periods of remission.

Clinicians should tell their patients that fluctuations are common, and monitor them to trigger a return to care if symptoms come back, the researchers say.

J. Clin. Psychiatry 85, 24m15395 (2024)

Spontaneous mutations point to risk genes

Genetics has an important role in ADHD, with previous studies estimating a heritability of 70–80%. Genome-wide association studies, which assess the contribution of common variants in single letters of the genetic code, can so far account for only around 15–30% of this, implying that rare variants might have an important role. But no specific risk genes have been identified with high confidence.

One study has analysed 152 children with ADHD and their parents, using whole-exome sequencing, which sequences only coding regions of the genome, and compared these with 788 previously sequenced parent–child trios without ADHD. The study, led by Emily Olfson at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, found that rare and ultra-rare de novo damaging mutations are up to twice as common in ADHD. These mutations occur spontaneously in an egg or sperm cell, and so are not inherited from either parent.

The study found 24 ultra-rare de novo damaging variants in people with ADHD that did not overlap with de novo variants seen in the control group, but did overlap significantly with risk genes for other neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric conditions, such as autism.

By combining their data with a previous large sequencing data set, the researchers identified KDM5B, the gene encoding lysine demethylase 5B, as a high-confidence ADHD risk gene, and estimated that about 1,000 genes contribute to ADHD risk. KDM5B is most commonly studied in the context of cancer, but it has also been linked to congenital heart disease, DNA repair, autism and neurodevelopmental disorders in general. The team also identified three other potential ADHD risk genes. Collectively, these genes indicate a role for processes in early neurodevelopment, such as tissue differentiation and neuron migration.

Nature Commun. 15, 5870 (2024)

ADHD, dyslexia and dyscalculia share genetic roots

ADHD, dyslexia and dyscalculia (impaired mathematical skills) occur together far more often than would be expected by chance. Understanding why this happens is crucial to intervening effectively. One possible explanation is that these conditions share common causes, either environmental or genetic. Alternatively, one of these conditions could contribute to causing another. For instance, learning difficulties could make lessons frustrating for a child, leading to symptoms of inattention, or vice versa, with an impaired ability to focus making learning more challenging. It is also possible that both of these dynamics are at work.

To untangle this problem, a team led by Elsje van Bergen at Vrije University in Amsterdam studied 19,125 twins from the Netherlands Twin Register, a national database on twins and their families. Each set of twins was assessed at ages 7 and 10. The researchers collected teachers’ ratings of ADHD symptoms, and scores on standardized tests of reading, spelling and mathematics.

The researchers first calculated the prevalence of the conditions and their co-occurrence. Children with any one of the conditions were roughly two to three times more likely to have a second condition. However, contrary to some previous higher estimates, only 23% of children with one condition also had another.

Twin studies compare identical twins, who share all their genes and most of their environment, and non-identical (fraternal) twins, who share only half of their genes but also share their environment. How much more similar identical twins are, compared with fraternal twins, indicates the extent to which a trait is determined by genetic factors.

The results indicated that the only trait that causally influenced another was the effect of reading ability on spelling. Correlations between all the other traits were attributable to common genetic influences, suggesting that ADHD, dyslexia and dyscalculia co-occur because they have overlapping genetic causes, rather than one causing another. This implies that interventions should target each condition separately, rather than assuming that treating one might improve the symptoms of the other, the researchers say.

Psychol. Sci. 36, 204–217 (2025)

Reduced stability of neural activity predicts impairment of cognitive control

A core symptom of ADHD is inhibitory dysregulation, which is difficulty suppressing inappropriate responses. Researchers think that moment-to-moment fluctuations in inhibitory control underlie certain ADHD symptoms, but previous studies have focused on time-averaged neural responses, which obscures this variability.

A study led by Zhiyao Gao at Stanford University in California used ultra-fast functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to assess the variability of brain responses to individual trials during a cognitive control task in children with ADHD and in control individuals without ADHD. This allowed the researchers to relate measures of neural variability to both fluctuating performance and clinical severity. They used a stop-signal task, in which participants repeatedly respond to frequent go signals, but have to inhibit their response when an infrequent stop signal occurs.

The study distinguished between reactive and proactive control. Reactive control involves suppressing a dominant (go) response in reaction to changed demands (a stop signal). Proactive control describes preparatory strategies individuals use when they anticipate needing increased control. In a stop-signal task, this typically involves slowing down all responses, as measured by reaction times.

Children with ADHD had more temporal variability and less spatial stability in their brain responses than controls did. This was seen in key regions of two brain networks involved in cognitive control: the salience network and the frontoparietal network.

Importantly, more temporal variability in a key region of both networks, the posterior cingulate cortex, correlated with inattention, suggesting that neural variability is directly related to the severity of ADHD symptoms. The team also found that, in children without ADHD, longer reaction times were associated with greater degrees of proactive control. The association between reaction times and proactive control was much weaker in children with ADHD, suggesting that their ability to use proactive control to slow their responses is less flexible.

Children with ADHD also had more variation in neural response patterns between individuals than controls did. This could reflect the fact that people with ADHD have diverse cognitive and clinical profiles, and might explain why previous studies have failed to identify neural markers of ADHD.

The researchers say that measures of neural stability illuminate the mechanisms underlying impaired cognitive control in ADHD. Such stability measures might serve as a useful biomarker, and they could inform the development of treatments aiming to enhance the consistency of neural responses, perhaps by using neurofeedback.

Nature Commun. 16, 2346 (2025)

ADHD is more prevalent in people with other diagnoses

The global prevalence of ADHD is estimated at 3.4% in children and 2.6% in adults. However, it often co-occurs with other psychiatric diagnoses, so the prevalence in people being treated for other conditions is probably higher. Two reviews published in 2022 arrived at wildly different figures for this, ranging from 6.9% to 38.8 %, probably because they included only 14 and 15 studies.

A 2025 meta-analysis of 311 studies, including almost 700,000 participants, was led by Simon Johnson of the North Metropolitan Health Service in Perth, Australia. The researchers estimated the prevalence of ADHD in clinical populations at 32.4% for children and 21.4% for adults, which is 8 to 9 times higher than in the general population.

The team also analysed possible modifying factors, including geographic region, year of publication and co-occurring condition. They found no evidence of change over time, from 1981 to 2023. There was more variation in prevalence by geographic region for children than for adults, which the authors suggest is due to differences in diagnostic practices and resources for paediatric mental-health services. People with autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder and tic disorders were most likely to also have ADHD.

The researchers hope that their findings can raise awareness among clinicians regarding underlying untreated ADHD in people with other psychiatric symptoms. They say that the study highlights the importance of screening, diagnosing and treating ADHD in people diagnosed with other conditions, because treating those conditions is less effective when underlying ADHD is untreated.