Credit: Sam Falconer

The typical human digestive tract is home to one of the densest communities of microorganisms on the planet. Bacteria dominate researchers’ attention, with the roles of other members of this ecosystem, such as tiny but abundant viruses, receiving less scrutiny. Perhaps the most neglected players of all, however, are also among the largest and most complex: single-celled organisms called protists.

Nature Outlook: The human microbiome

As nucleus-containing eukaryotes, protists bear more resemblance to human cells than they do to bacteria. Anything larger than a bacterium in a stool sample has typically been cast as a villain, and that includes protists. “Medical school told physicians that we shouldn’t have them,” says Mark van der Giezen, a biologist at the University of Stavanger in Norway. The clinical reflex is to rid the body of protists with antibiotics, such as metronidazole.

In some cases, this instinct is sound: the notorious parasites Giardia and Cryptosporidium, which can trigger stomach cramps and diarrhoea, are protists that you are better off without. But many people live with protists in their gut that do not seem to cause disease. The balloon-shaped Blastocystis, for example, is estimated to be present in more than one billion people, and is especially common in low- and middle-income countries. Not only does this typically not cause problems, but some researchers also think that the presence of these protists might be beneficial, helping to control gut bacteria and supporting a healthy immune system.

As the positive case for having these complex microbes around builds, some researchers are beginning to consider whether they might one day be introduced deliberately to restore gut health or fight inflammatory conditions, such as irritable bowel disease. The wisdom of this is not yet certain, because protists are still understudied members of the gut community. But what is fast becoming clear is that they are not always the villains that they have been made out to be.

Lost friends

In the modern human gut, protists are the outliers in a bacterium-dominated landscape. In herbivores, however, the microbes are plentiful: single-celled eukaryotes comprise much of the microbiota in the stomach of a cow, for instance, contributing perhaps half the microbe biomass. And a 2020 study of pigs found four groups of protists that were present in 80% of the animals1. “Pigs are probably the mammal that most resembles humans, apart from non-human primates, and they have a lot of protists,” says Rune Stensvold, an intestinal-protist researcher at the Statens Serum Institute in Copenhagen.

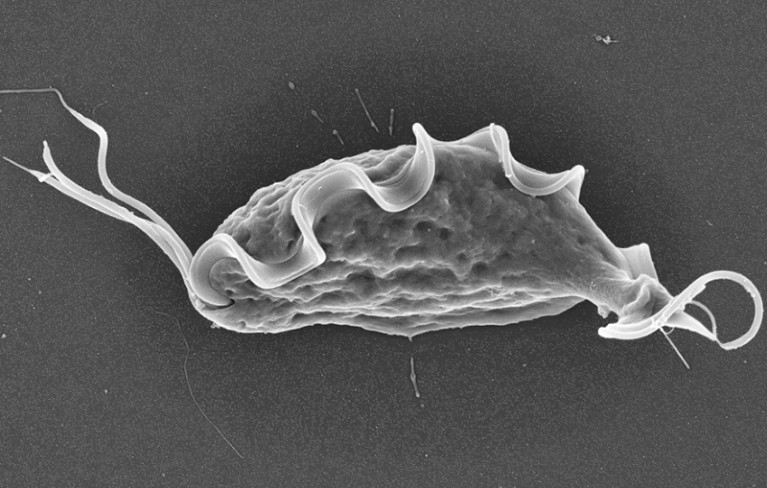

The protist Tritrichomonas musculus.Credit: ref.5

The most common protist in the human gut is Blastocystis, which is related to brown algae and the fungus-like water mould Phytophthora infestans (responsible for the Irish famine in the nineteenth century). The protist is found more often in people in non-industrialized countries, and is more numerous in those who consume significant quantities of fibre and plants. One large study, led by researchers at the University of Trento in Italy, found Blastocystis in less than 7% of North Americans, around 20% of Europeans and more than 35% of people in Tanzania, Ethiopia and Cameroon2. This has led some researchers to think of Blastocystis as a natural component of the gut microbiota that has been lost in some parts of the world, owing to changes in lifestyle. “I strongly believe that Blastocystis could be one of the organisms in the ancestral microbiome and we started losing it due to changes in diet,” says Anastasios Tsaousis, an evolutionary parasitologist at the University of Kent in Canterbury, UK.

Protists known as parabasalids, which sport whip-like flagella for propulsion, are also more common in non-industrialized communities. These microbes inhabit the guts of termites and help them to digest woody material, but at least two species have now been found in the human gut. “Earlier microbiome studies were often done on the populations surrounding the scientists doing that work,” says Michael Howitt, an immunologist at Stanford University in California. This might have caused protists to be overlooked initially, owing to their relative scarcity in industrialized countries.

Elias Gerrick, a microbiologist at the University of Chicago in Illinois, thinks that Western hygiene standards have played a part in the reduction of gut protists in this population. The Trento-led study2 found none present in babies, suggesting that protists are obtained through contact with other people or the environment. But the cleaner the environment is, the less opportunity there will be for that to happen. Protists “are more susceptible to increased sanitation than a lot of bacteria, because many don’t survive long in the environment”, Gerrick says.

But improved hygiene practices also reduces transmission of parasitic worms and nasty microbes — hardly a misguided intervention. Nevertheless, some researchers are investigating what beneficial actions by protists in the gut might have been lost owing to modern hygiene standards and diets.

Outsized influence

Certain communities in Tanzania typically have a more diverse gut zoo than is present in the average Californian, for example. “Hunter-gatherer tribes have tons of microbial diversity, teeming with protists, whereas all the industrialized populations are pretty much bare,” says Gerrick. Higher bacterial diversity is linked to a lower body mass index and better health, and several studies have shown that people who carry Blastocystis have a much more diverse community of bacterial species than do those without the microbes3,4.

Kevin Tan (left) studies a subtype of Blastocystis.Credit: Kevin Tan

“We’re reaching a consensus that Blastocystis is not a bad bug,” says Eleni Gentekaki, a microbial ecologist at the University of Nicosia in Cyprus. “It’s correlated with a healthy gut.” What remains unanswered is whether this protist is an indicator or a manipulator — does it choose to make its home in already-healthy gut communities, or does its presence improve health?

Some animal studies suggest that protists do actively tweak microbial ecosystems. “There’s often depletion of specific groups of bacteria for each protist,” says Gerrick. In some cases, this might be due to protists outcompeting resident bacteria. In mice, for example, the parabasalid Tritrichomonas musculus has been shown to severely dampen or eliminate Bifidobacterium and Turicibacter species — probably by starving them of the dietary fibre that all three consume5. The protist Tritrichomonas casperi, which eats gut mucus, similarly squeezes the mucus-eating bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila out of the mouse intestine5. These examples bolster the argument that protists can shape the microbial make-up of the gut, but their impacts on health remain equivocal. “The effects of the bacteria could be beneficial for certain disease and detrimental for others, in which case elimination by the protists could be good or bad,” Gerrick explains.

There is evidence of protists excreting specific compounds that affect the make-up of the gut microbiota. Some tritrichomonad species in mice, for instance, spew out succinate. Humans make this small compound when generating energy inside cells, but it can also signal inflammation. Succinate levels have been found to be elevated in gut tissue removed from people with Crohn’s disease, for example6.

Some researchers think that succinate produced by protists could be interpreted by the immune system as an unwanted bloom of bacteria or parasitic worms. Specialized cells in the lining of the gut known as tuft cells are activated by succinate. These cells respond by launching an immune response, intended to restore the gut ecosystem, that ramps up inflammation. “It doesn’t harm the host, but it does have a huge impact on the lining of the gut,” says Gerrick. One effect is lengthening the gut, possibly to compensate for an uptick in the abundance of tuft cells and maintain nutrient absorption levels.

Further evidence of protists pulling levers in the immune system can be found in a pair of 2016 studies that showed that T. musculus worsened colitis, another inflammatory gut disease, in mice7,8. Howitt compares protists with elephants on the African savannah: they are not the most numerous creatures, but they are large and they can adapt their ecosystem by knocking down trees to preserve the grasslands. “We’re seeing protists shaping their environment, influencing the immune system,” he explains.

“I call them a vocal minority,” says Kevin Tan, a microbiologist at the National University of Singapore. “They can be few but they exert a large ecological, immunological and health impact.”

Whether that impact is beneficial or not, however, is not always clear. For example, in 2025, researchers reported that succinate release driven by T. musculus in the mouse gut triggers an immune response in the lungs that can exacerbate asthma, but that also boosts the response to tuberculosis bacteria9. Others have shown that a close cousin, T. muris, promotes immune action against parasitic worms10. “Ultimately, some could be protective against infections, but may exacerbate other inflammatory diseases,” says Howitt.

Human evidence

The Trento-led study2 shed considerable light on the link between protists and human health. The analysis of nearly 60,000 people across 32 countries showed that the presence of Blastocystis in a person’s gut was tightly coupled to better heart and metabolic health, lower rates of obesity and fewer markers of inflammation. Those who ate higher quantities of unprocessed plant-based foods, such as avocados, dried fruits, nuts, seeds, legumes and green vegetables, were more likely to be colonized by Blastocystis.

The presence of Blastocystis usually corresponds with a rise in Firmicutes bacteria, which ferment fibre and generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). The production of these small molecules flicks switches in the human immune system, dampening inflammation and creating conditions that are hostile to harmful bacteria. Bacterial genera such Escherichia, Bacteroides, Klebsiella and Pseudomonas, all associated with poorer gut health, were more abundant in people without Blastocystis.

Stensvold says that research suggests Blastocystis is more common in healthy humans than in those with inflammatory bowel conditions. And an analysis of more than 500 people returning to Germany from the tropics11 found that Blastocystis was more common in those without gastrointestinal symptoms.

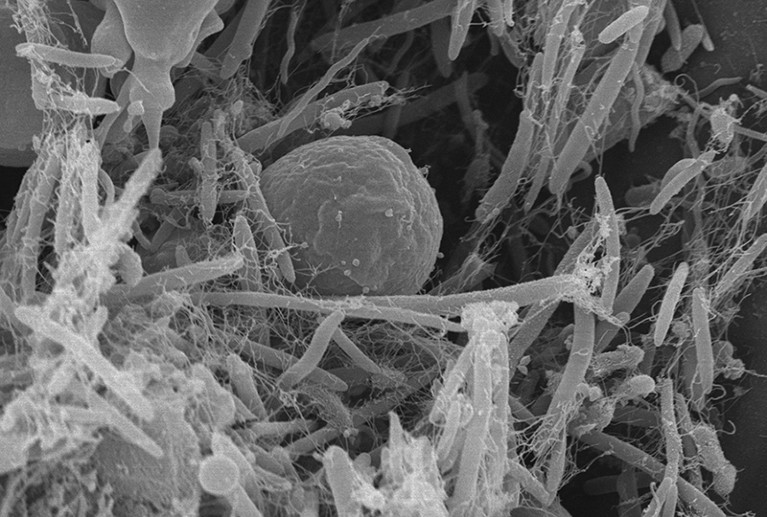

This all paints a rosy picture of Blastocystis and human health, but there is a twist. At least ten Blastocystis subtypes have been found in humans, and they can have different effects on health. “Around 95% of humans with Blastocystis carry subtypes 1 to 4,” says Stensvold. Some studies have found correlations between specific Blastocystis subtypes and good gut health. Subtype 4, for example, is thought to benefit healthy gut bacteria and inhibit the growth of Bacteroides vulgatus, a common pathogen12.

Other subtypes might bring unwelcome health implications. “In southeast Asia and Singapore, I believe we have a bad Blastocystis,” says Tan. His laboratory has been studying subtype 7, which is rare in many parts of the world but common in Singapore. The team’s work suggests that this type of Blastocystis can generate a compound that stokes inflammation and works with Escherichia coli to kill off Bifidobacterium — viewed as beneficial gut bacteria.

Tan suspects that this subtype crossed to people in southeast Asia from waterbirds, in which it is common. This could partly explain its negative effects. “We can’t rule out that some avian subtypes, which we have not adapted to, cause distress in the bowel,” says Stensvold. Previously, Tan and his colleagues found that subtype 7 ratcheted up inflammatory agents and increased the proportion of harmful bacteria in the guts of mice, while subtype 4 boosted beneficial bacteria and SFCAs, and offered some protection against colitis13.

Making introductions

Some scientists have suggested that protists might one day be purposefully introduced to the gut as a way to improve health. “If Western diets have removed a top organism from the gut ecosystem, then maybe that’s why we see high incidence of autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammation,” says van der Giezen.

Blastocytis subtype 7 (centre) can have negative effects in people.Credit: Benoit Mallaret and Thet Tun Aung

Currently, the unknowns seem too great to take such action. Protists such as Blastocystis have much larger and more complex genomes than do bacteria — around 20 million base pairs for some Blastocystis subtypes, compared with fewer than 5 million for the bacterial pathogens Salmonella spp. and Clostridium difficile. And because protists have significant metabolic flexibility, with multiple genes and enzymes able to work on the same compounds, the effects that these organisms have on the gut could depend on the conditions, and be difficult to predict. Moreover, protists can also be difficult to grow in a lab. With so much uncertainty, therapeutic use seems a distant prospect, particularly because the study of the organisms remains a niche pursuit.

There are, however, signs that attitudes towards these microbes are beginning to change. For example, under some health-care guidelines, the presence of Blastocystis is cause to blacklist an individual from donating fecal matter for use in a transplant (an established and effective treatment for C. difficile infection, and under investigation for myriad other uses). “In some countries, it is not allowed to have Blastocystis in the donor stool,” says Stensvold. But “here in Denmark, the physicians do not care about it”.

This position is supported by a small Dutch study, which reported that the transmission of Blastocystis to people receiving a fecal matter transplant (FMT) for C. difficile did not cause gastrointestinal upset14. In another study15, three people received FMT that contained Blastocystis subtype 3. Two were initially colonized by the protists, but the microbes were lost within six months; the third recipient already had subtype 2, and was not colonized by the donor’s subtype. A European Union project is investigating the ecology of these protists in people. The long-term hope, Tsaousis says, is to “convince the FMT companies to involve certain Blastocystis subtypes in future FMTs”.

People might not be ready to swallow them in a pill, but protists’ potential benefits to health means that they are a rising star of gut health. Their size, variation and intricacy will make understanding them a lengthy process. But that’s also what makes them interesting. “It is freaking amazing,” says Tsaousis, “that such a simple organism is biochemically so very complex.”