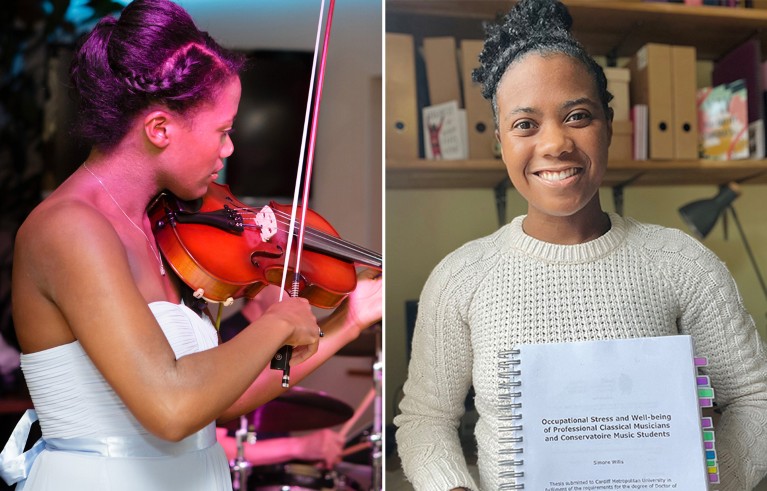

As a part-time PhD student, blocking out time both work and study helped Simone Willis to keep a good work–life balance.Credit: Paul Goode Photography, Simone Willis

When I enrolled for a part-time PhD in 2016, it was for flexibility and financial reasons. I was working as a music tutor across Cardiff and South Gloucestershire, UK , teaching violin, flute and fife. These experiences, coupled with an undergraduate degree in music, led me to apply for a PhD exploring workplace stress and well-being in classical musicians and people studying at US conservatoires.

In the second year of my PhD, I accepted a part-time job at Cardiff University as a systematic reviewer, alongside my studies. Given the topic of my thesis, I wanted to to maintain a healthy work–life balance. Since graduation, I’ve stayed in that role, assessing medical devices and conducting evidence-synthesis projects in health and social care. I’ve also co-authored 13 papers examining mental health and well-being across a variety of sectors and settings. Using my experiences as inspiration, here are seven tips that helped me to balance my work, study and well-being during my PhD.

1. Treat your PhD like a job

I set boundaries for splitting my 9-to-5 week between work and study. This meant a 50/50 split of my working hours. Before I started my job as a reviewer, I spent 20 hours a week teaching music and 20 hours on my PhD.

Aside from a few late nights and weekends, I treated my PhD exactly like a part-time job. I blocked out time in my diary for both work and study, which helped me to plan and keep focused. Sticking to these boundaries allowed me to decompress and make time for friends, family and hobbies. I’d leave the office to attend a dance class and then catch up with my husband over dinner. Studying part-time meant that the PhD was not an all-consuming process and provided perspective — life outside the PhD continued.

2. Leave tasks incomplete

When switching between work and study, I often needed to pick up a train of thought from a few days before. A technique that worked well was writing a list of any uncompleted tasks at the end of my day, either scribbled on a sticky note on top of my keyboard, or as a comment on a document. These helped me to pick up ideas again later without needing to mentally retrace my steps. For example, if I was in the middle of writing a paragraph in the discussion section of my thesis, I’d leave a note to say, “Describing x finding, relate to y theory”, before heading off.

At first, leaving paragraphs with half-finished sentences or suggestions on where to take my writing felt counter-intuitive, but making these notes allowed me to write without losing momentum and gave me time for reflection.

3. Be realistic about what you can achieve in the time available

Early on, I was overambitious when planning my studies, which led to frustration. For example, I planned to complete background reading and write my literature review in the first three months. In fact, this took much longer and was something I returned to in the final stages of putting together my thesis.

Over time, I developed a better sense of how long tasks would take, especially writing, and learnt to plan accordingly. I found a system that allowed me to write fluidly. First, I mapped out an overarching structure for my thesis, using headings and bullet points in a document. Second, I identified references and noted where they would go in the structure. Only then did I turn to writing each section in detail. In the final stages of writing my thesis, I was able to accurately map out monthly, weekly and daily writing tasks.

4. Be selective when saying ‘yes’

I also learnt to value my time and consider what opportunities to take on. It is tempting to say ‘yes’ to every opportunity that comes along, but I developed skills in being selective and saying ‘no’ when needed.

I made my decisions by reflecting on the following: have I already done something similar? Is this opportunity something I want to do or something someone else wants me to do? Do I realistically have the time? Is this a one-time-only opportunity or will there be similar chances in the future? What are the potential benefits and harms of saying ‘yes’ or ‘no’?

In my second year, I chaired the doctoral-researcher committee, which organized events and represented PhD students on academic committees. I remember being asked whether I would be on the committee for another year, and my instinct was to say ‘yes’. But after a moment of reflection on those key questions, I realized that it was better to focus on my research. I ensured that the committee was in a good position and had recruited new members before I left.

5. Connect with peers

Sharing the journey with other PhD students was invaluable for receiving advice, celebrating the highs of publication and sharing the challenges and setbacks of data collection gone awry.

I was initially registered on an master’s leading to a PhD, so had to formally transfer onto a PhD programme in my second year. I needed to submit a written report as well as pass an interview. I remember speaking to Helen, one of my peers, about the process and she advised me on how to structure my application and we discussed the questions asked in her interview. This helped me to prepare for the interview and understand the strengths and weaknesses of my work.

I also worked in a shared office alongside 15 other PhD students. This space allowed me to connect with students at different points in their studies and be part of a community of doctoral researchers. More widely, talking to friends in other professions helped to keep the PhD in perspective and understand that there are many ways to be successful.

6. Communicate regularly with supervisors

Early on in my PhD, my director of studies suggested that I send an agenda ahead of meetings with my supervisors. This gave each meeting purpose and clarity in the topics to discuss. This was especially helpful in the write-up phase, when I needed to discuss different chapters and consider the thread throughout my thesis. To keep momentum, before each meeting ended, I scheduled the next meeting.

After each meeting, I sent a brief summary over e-mail, which allowed me to revisit important decisions later in the project. It was important to discuss issues before they escalated into bigger problems — my supervisors were a source of support and encouragement throughout my PhD.

7. Write as you go

When I first started, I had no concept of what 80,000–100,000 words looked like — only that it sounded like a lot. I was advised early on to write throughout the PhD process and not leave everything to the end. This appealed to me because I like having a plan and was concerned that I’d forget why I had made particular decisions if I left the writing until the end. Initially, however, I felt like I was getting nowhere, constantly redrafting and not knowing what direction to take with each individual chapter. Because my music degree was performance-based, I hadn’t had much practice writing in an academic style and it took me a while to develop my academic voice.

One thing that really helped was writing the manuscript for the first study from my thesis. This helped me to improve the structure of my work and to communicate an argument. Writing also helped me to clarify my understanding of the research area.

Although inspired by my experiences and those I interviewed working in music, I hope that these tips are transferrable to graduate students in a variety of disciplines.