Animals

Mice were maintained on a 12 h–12 h dark–light cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. The temperature was maintained at 22 °C and the humidity was controlled at 30–70%. All experiments were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines and approved by the Harvard University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Except for experiments on mutant strains affecting sensory input, C57BL/6J mice (RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664) were used for all sequencing experiments. Mothers of all C57BL/6J experiments subjects were placed in a fresh cage when embryos were ~E12. For samples collected at P28 and P65, mice were separated from parents and opposite-sex siblings at P21 and group-housed, then kept separated from the opposite sex until dissection. C57BL/6J brains were collected during the first 3 h of the dark cycle. Cnga2, Trpc2 and Trpm8 mutants were treated the same, whereas Piezo2 and Gabrb3 conditional knockout mice and littermate controls were raised in another facility (Harvard Medical School) and thus brains were collected over a wider time window (2–7 h into the start of the light phase of 12 h–12 h light cycle). For dark-rearing experiments, pregnant mice were ordered from Charles River Laboratories (RRID:SCR_003792) and delivered to Boston Children’s Hospital’s Animal Behaviour and Physiology Core, where they were then housed either in constant darkness (cage changes performed with night-vision goggles) or standard 12 h–12 h light–dark conditions (control group). Biological replicates never contained brains from sibling pairs, although sibling pairs were occasionally pooled into one sample. All mutant experiments were performed with equal numbers of male and female samples, except for Cnga2 knockouts in which only males were used due to the location of Cnga2 on the X chromosome and impairments of Cnga2 mutants in suckling and mating. Cnga2 knockout mice, always males, were generated by crossing heterozygous mothers to FVB fathers leading to hemizygous male progeny. Piezo2 conditional knockout mice were generated using Cdx2-cre, which drives recombination in neurons (including touch sensory neurons) and some peripheral tissues below cervical level C2, and either Piezo2fl/Piezo2fl or Piezo2fl/Piezo2−. Brains from Piezo2 conditional knockout mice were collected at P10, P18 or P19, and show motor defects, thus were frequently provisioned with extra food and gel packs placed on the cage floor; because of these defects, we did not raise animals beyond P19 for experiments in adults. We also did not profile Trpm8 as adults, because thermoregulation maturation occurs mostly before P18. Gabrb3 conditional knockout mice were generated using Avil–cre, which drives recombination in all dorsal root ganglion and trigeminal sensory neurons, and heterozygous Gabrb3fl/+ mice, which is sufficient to cause touch hypersensitivity55. Brains from Gabrb3 conditional knockout mice were collected at P60–P70. Mutant and transgenic strains used in this study were previously published and include (with Jackson Laboratories (RRID:SCR_004633) numbers where applicable): Trpc2 knockout mice51 (021208; RRID:IMSR_JAX:021208); Cnga2 knockout mice57; Trpm8 knockout mice71 (008198; RRID :IMSR_JAX:008198); Piezo2fl (ref. 72) (027720; RRID:IMSR_JAX:027720); Piezo2− (ref. 73); Cdx2–cre74) (009350; RRID:IMSR_JAX:009350); Avil-cre75, Gabrb3fl (ref. 76), and Opn5-cre77. Sample sizes were chosen to match or exceed those in similar experiments from relevant studies.

Single-nuclei sequencing

Brains were dissected (P10+) or whole heads were removed (E14 to P4), frozen in optimal cutting temperature medium and placed at −80 °C. The POA and surrounding regions were dissected on a cryostat at −15 °C using the Paxinos Developing and Adult Brain Atlases78,79 to determine locations for dissection based on landmarks. At all ages, tissue was collected from the anterior-most portion of MnPO to the posterior-most portion of the POA. To achieve this, after slicing away anterior material, thin (10–20 µm) sections were collected and examined under a dissecting microscope to identify landmarks. At E16 to P65, the anterior commissure on each brain hemisphere is distinctly visible and moves medially as the brain is sliced from anterior to posterior. When the medial edge of the anterior commissure lined up underneath the ventral tip of the lateral ventricle, we began collecting tissue for sequencing. At E14, the anterior commissure is not clearly visible; we instead began collecting tissue when we first saw the ventral tips of lateral ventricles reach their full extents. To collect tissue, we first used a razor blade to remove large blocks of tissue lateral to the lateral ventricles, and then sliced 200-µm-thick sections to collect roughly the ventral-most one-third of the brain into a 2-ml tube. At E14, we collected 800 µm; at E16–P4, we collected 1.2 mm and at P10–P65, we collected 1.4 mm. Dissected tissue was placed in a 2-ml tube and kept at −80 °C until the day of library preparation. For library preparation, 4–8 samples were prepared simultaneously, pairing mutant and control and male and female samples on the same day. Dissected tissues from three mice (C57BL/6J samples; two replicates per age per sex) or 2–3 mice (mutant and control samples; replicate numbers indicated within Fig. 5 legend) were pooled for each sample. Two female and two male samples were collected at each of the eight ages, except for E16 where only one female and one male sample were collected. Nuclei preparation was modified from 10X Genomics demonstrated protocol CG000375. Samples were dounce homogenized in a 3-ml Potter-Elvehjem Tissue Grinder in a 4 °C cold room in 0.1% NP40 lysis buffer, passed through a 70-µm filter (MACS Smart-strainer) and centrifuged at 500g for 5 min. All buffers contained 1 U µl−1 RNase Inhibitor (Sigma Protector) and centrifugation steps in nuclei preparation was done at 4 °C. Nuclei were resuspended in PBS with 2% BSA, then passed through a 20-µm filter (MACS Smart-strainer). 7-AAD was added and nuclei were separated from debris by fluorescence activated cell sorting. Following centrifugation, nuclei were permeabilized in 1× lysis buffer (10X Genomics, CG000375), then centrifuged and resuspended to a concentration of roughly 6,000 nuclei per µl, using a Luna Cell Counter. Downstream preparation of sequencing libraries was carried out using the 10X Genomics Multiome Kit. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 200 flowcell (eight samples per flowcell of either RNA-seq only or ATAC-seq only, targeting 200,000 reads per cell) using instructions provided by 10X Genomics Multiome protocol (read 1 = 26 bp, i1 = 10 bp, i2 = 10 bp, read 2 = 90 bp; ATAC read 1 = 50 bp, i1 = 8 bp, i2 = 24 bp, read 2 = 49 bp), to a saturation of at least 70% for each run. Paired-end sequencing with read lengths of 100 nt was performed for all samples.

snRNA-seq analysis

Illumina sequencing reads were aligned to the mouse genome using the 10X Genomics CellRanger ARC pipeline with default parameters. For the C57BL/6J dataset, the mean numbers of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and genes per cell were 5,276 UMIs and 2,264 genes for all neurons. Raw reads and output are available on GEO at accession: GSE280964 (RRID:SCR_005012).

For initial analysis, we relied on the R package Seurat (RRID:SCR_016341) and standard data analysis practices. We filtered out nuclei with more than 400 or fewer than 100,000 UMIs, with fewer than 250 genes and with more than 20% of UMIs belonging to one gene. Although rare, nuclei with more than 10% mitochondrial or ribosomal UMIs and more than 1% IEG, apoptotic or red blood cell UMIs were also filtered out. We defined the main cell classes (glia, neurons) and separated out inhibitory and excitatory neurons using Seurat clustering and known marker gene enrichment.

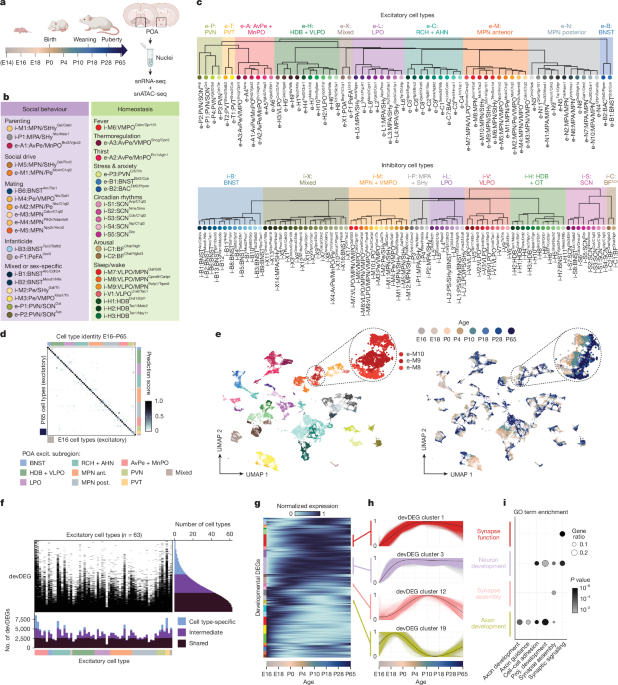

Defining cell types

Cell types were defined separately among inhibitory and excitatory neurons using the same procedure. First, SCTransform80 was used to normalize all C57BL/6J data across all ages, regressing out percentages of mitochondrial UMIs, ribosomal UMIs and largest gene. Each cell from this dataset was then mapped to the published POA reference atlas1, separately for scRNA-seq and MERFISH reference atlases, using canonical correlation analysis-based label transfer21. Both reference datasets were normalized using SCTransform, and FindTransferAnchors was run using the SCTransform assays, PCA as the reference reduction and 50 principal components. TransferData generated predictions to reference atlas cell types using 50 principal components. Each cell was then assigned (1) a scRNA-seq, and (2) a MERFISH reference atlas predicted cell type, if the top prediction score exceeded 0.6; otherwise, a predicted cell type label was not assigned. These predicted cell type labels were used to guide subsequent clustering and cell type definition.

Then, P65 neurons were subset out to initially define cell types in adult neurons. Seurat functions RunPCA and FindNeighbors were run (150 principal components) and FindClusters (resolution 12) was used for an initial round of clustering. This generated clusters that often, but not always, had clear matches to POA reference atlas clusters, in terms of (1) majorities of cells predicted as a single MERFISH and/or scRNA-seq cell type (as described above) (Extended Data Fig. 1b), with scRNA-seq and MERFISH cell types matching as described in the POA atlas paper1; and (2) marker genes matching those described in the POA atlas paper1. Each cluster was assigned a cell type ID, with occasional grouping of 2–4 clusters that mapped to identical sets of reference atlas cell types. Grouping of clusters into subregional groups was determined by correlation analysis (Extended Data Fig. 3e,h) and previous knowledge about spatial location from MERFISH (Fig. 5c and supplementary figure 18 of ref. 1). In cases where cell types lacked clear matches to MERFISH data, we estimated location based on three-colour RNA scope staining and Allen Brain In Situ Hybridization Atlas data. Dendrogram plots were generated using the R package dendextend.

Having defined cell types at P65, we next mapped younger ages iteratively onto older ones (P28 to P65, then P18 to P28 + P65 and so on). For this, we subset each younger age, processed those data as described above for P65, then used FindTransferAnchors and TransferData as described above but with 150 principal components and with older ages as the reference atlas, to generate prediction scores for each cell. Cells with top prediction scores exceeding 0.8 were assigned to that cell type ID. Cells with top prediction scores exceeding 0.5 were also assigned to that cell type ID, as long as the prediction score was at least twice as high as the second-best prediction score. We chose these thresholds by exploring how well de novo clustering at each younger age generated clusters with homogenous predicted cell type ID labels. This procedure generated cell type IDs for 90% or more of cells at older ages, with lower percentages around P0 and earlier, which could be due to less precise dissection of smaller brains and thus inclusion of cells from brain areas not included at older ages. Prediction scores for cells that passed these thresholds are plotted in Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 3b,c, averaged within a cell type. Identity ratio in Extended Data Fig. 3c is calculated using matrices in Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 3b: the value on the diagonal (best cell type match) minus the top off-diagonal value (second-best cell type match), divided by the value on the diagonal. Cell types in mutant and control samples were determined using the same procedure, except that cells were label transferred onto all ages. This procedure assigned cell type IDs to 80–90% of cells in these samples, an accuracy similar to across-age mapping in C57BL/6J samples. The remaining 10–20% of cells not assigned IDs in this manner were removed from further analysis.

To identify cell types in visual cortex at P10 from Trpc2 mutants and control littermates, we took a similar approach, using P8 and P14 visual cortex datasets as a reference atlas from ref. 7. We normalized P8 and P14 visual cortex data using SCTransform, used 150 principal components to perform label transfer and used cut-offs as described above to assign predicted cell type IDs. In our samples, 93% of cells were assigned predicted cell type IDs by this procedure.

Regionalization quantifications

Matrices in Extended Data Fig. 3d,e,g,h were calculated by averaging scaled RNA values among all cells within a cell type, then calculating the Pearson correlation between all such cell type vectors. Correlations among cell types within a region were averaged to generate Extended Data Fig. 3f,i. Seurat’s FindAllMarkers function was used to identify regional marker genes in Extended Data Fig. 3j–l, using an adjusted P value cut-off of 0.05. Plots were generated using ComplexHeatmap (RRID:SCR_01727) and pheatmap (RRID:SCR_016418) R packages.

devDEG analysis

The devDEG analysis presented in Fig. 1f–i (and used to calculate heatmap data in Extended Data Fig. 7e,f and refinement score in Fig. 3b) comprises a combination of R and Python scripts described previously27 (https://zenodo.org/records/7113422) that we adapted. Each cell type was subset across all ages, then sample-pseudobulked (n = 4 samples per age, except n = 2 at E16) and passed to the limma-voom pipeline81 from the edgeR (RRID:SCR_012802) package82 for differential expression analysis testing. To implement this, a Python v.3.10.9 conda environment was created to install and isolate all necessary packages. We subset Seurat objects by cell types (inhibitory, excitatory), then converted them first to H5 format (with SaveH5Seurat) and then to h5ad format for import in scanpy (with the Convert function from the SeuratDisk package https://github.com/mojaveazure/seurat-disk). We created cell type–data point batches using 02.pseudobulk-by-batch_limma-voom_data-prep.ipynb notebook. We detected DEGs with edgeR/limma-voom using 10_major_trajectory_devDEG.R R-script, defined as those with false discovery rate (FDR) < 5%. We fit linearGAM trends (generalized additive models) with LinearGAM (https://pygam.readthedocs.io, 11__dev-DEGs_age-trend-fits_rate-of-change.ipynb) for every gene across time points. We plotted trends using matplotlib (12__major-trajectory_dev-DEGs_stage-trend-fits.ipynb) (RRID:SCR_008624). We performed hierarchical clustering of DEG trends with 14__stage-trend-fits_clustering.ipynb and plotted the figures with matplotlib. This step was memory intensive and required up to 210 Gb of RAM for the largest dataset in our analysis. For each DEG cluster we performed Gene Enrichment Analysis (15__Trajectory-devDEG_Gos-terms.ipynb) and gprofiler2. We plotted cell type and time point expression heatmaps for genes in GO categories (16__Eigentrends-of-selected-GO-terms.ipynb).

For Fig. 2l, we used a combination of GO terms and the SynGO knowledge base on biological process ontology terms (ref. 83, Supplementary Table 2, Biological process tab) to highlight expression values in GO categories in our dataset. We selected all categories that included the terms ‘synapse’, ‘synaptic’, ‘dendritic’, ‘neurotransmitter’ and other key words to capture relevant categories in the SynGO knowledge base. A GO term is represented by a set of genes. We overlapped DEG detected in each cell type across time points with genes in the selected GO category, and plotted expression heatmaps for categories in which the median number of overlapping genes was more than or equal to 40 when calculated across all cell types.

Analysis of E14 sequencing data

E14 cells were passed through initial quality control steps using the same cut-offs as all other datasets. Cell cycle gene list was obtained from https://github.com/hbc/tinyatlas/blob/master/cell_cycle/Mus_musculus.csv and used to create cell cycle scores with Seurat’s CellCycleScoring function (Extended Data Fig. 5a). All cells were clustered using Seurat’s unsupervised clustering pipeline with FindNeighbors (dims 1:50) and FindClusters (resolution 1.5). Clusters were then split into neuron or progenitor subsets using markers for mature neurons (Rbfox3, Syt1 and Stmn2) or progenitors (Neurod1, Neurog1, Hes1, Hes5, Hes6, Emx1, Sox2, Sox9, Lhx2 and Ascl1). Neurons were mapped to cell types in the E16–P65 dataset using the label transfer method described above (‘Defining cell types’ section) (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Identity score (Extended Data Fig. 5e,f) was calculated as the value on the diagonal of Extended Data Fig. 5d, where cells were mapped to P65 cells. Progenitors were clustered using Seurat’s unsupervised clustering pipeline with FindNeighbors (dims 1:50) and FindClusters (resolution of three) (Extended Data Fig. 5h). Progenitor cells were mapped to E16 regions using the label transfer strategy described above, with the same thresholds (Extended Data Fig. 5j), although removing thresholds completely did not qualitatively change the result.

Developmental trajectory quantification

To calculate developmental trajectories as in Fig. 2a–c, we followed the approach described previously28, to calculate distance between centroids in high-dimensional principal component space. We subset each cell type across all ages, performed SCTransform to normalize and identify 2,000 highly variable genes, and performed PCA (100 principal components). We then decided how many principal components to use for each cell type by asking how many of the top principal component are needed to explain 20% of variance in the data; if more than 100 principal components were needed, we used 100 principal components. We then found the centroid at each age for each principal component in gene expression space, and calculated the Manhattan distance between each centroid and the P65 centroid. This gives us a distance value for each age relative to P65. This distance generally decreased with age, indicating maturation, but on occasions in which it increased, we set the distance value at the later age to that of the previous age. This step partly excludes transient movement away from adult (for example, the transient upregulation of gene expression programs related to axon guidance, which may be low at early and late ages but high at intermediate ages), but allowed us to better quantify how ‘adult-like’ each cell type is at each age.

We also performed nearest neighbour analysis as an alternative measure of maturity state (Extended Data Figs. 6e and 9a), following the method described previously27 and associated code downloaded from https://zenodo.org/records/7113422. We focused on each cell type individually and constructed k-nearest neighbours graphs that included all age categories, with each graph comprising 50 neighbours. To assess the maturity level for each age group, we calculated the fraction of nearest neighbours that originated from adult nuclei. This involved tallying the number of adult nuclei serving as nearest neighbours to the nuclei of a specific age. Subsequently, we normalized this total by the overall count of nearest neighbours, thereby deriving a proportion that reflects the maturity state based on the presence of adult nuclei among the nearest neighbours.

Signalling gene expression analysis

All gene expression quantifications plotted were performed using log-normalized counts (that is, Seurat’s RNA assay, data slot). We compiled lists of genes belonging to various signalling classes (Supplementary Table 3, based on refs. 84,85) and computed module scores using Seurat’s AddModuleScore function. Module scores were averaged among cells within an age and then z-scored across age. Refinement Score was calculated for each gene set by first summing the number of significant devDEGs (‘devDEG analysis’ section above) between P10 and P65 and then normalizing by dividing by the number of gene × cell type combinations (after excluding combinations for which no expression is found at any age).

NeuronChat analysis35 was performed following tutorials from https://github.com/Wei-BioMath/NeuronChat. Ligand–receptor interactions present in the hypothalamus but not in the original interaction database were added using The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology85 (Supplementary Table 4), and then all links that were not neuropeptide and monoamine links were removed. run_NeuronChat was run using M = 100, mean_method = ‘mean’ and FDR = 0.01. Links with ligand abundance less than 0.025 were filtered out.

Distance analysis to determine male–female or mutant–control differences

We adapted a distance metric analysis described previously28 (similar to that used in ref. 86 for analysis of neuronal activity data) to ask whether (1) male and female or (2) mutant and control samples cluster in distinct regions of high-dimensional PCA space, separately for each cell type. To calculate distances between sample centroids, we used procedures and parameters similar to those described above for developmental trajectory calculation. We subset each cell type and, including both male and female or mutant and control samples, performed SCTransform to normalize and detect 2,000 highly variable genes, and performed PCA (100 principal components). We then decided how many principal components to use for each cell type by asking how many of the top principal components are needed to explain 20% of variance in the data; if more than 100 principal components were needed, we used 100 principal components. Then, for each sample (for example, four male and four female samples), we quantified the sample’s centroid in principal component space. We then calculated the Manhattan distance between all pairs of sample centroids. Our effect size (‘Male-female PCA distance, normalized’ or ‘Mutant-control PCA distance, normalized’) was calculated as the average across all male-to-female or mutant-to-control distances, normalized by the average of intra-sex or intra-genotype distances. This ratio quantifies how separated genotypes or sexes are compared to separation within each group. We calculated a two-sided t-test P value between all inter-sex versus intra-sex distances, or all inter-genotype versus intra-genotype distances. In Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 9b,c, any raw P value greater than 0.05 was considered not significant and results were validated by sexDEG analysis. For Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 10a, Benjamini–Hochberg multiple comparisons corrected adjusted P values were used to determine which cell types were NS. For sex analysis, to increase our n number, we included control samples from mutant–control experiments. For mutant analysis, to increase our n number, we included C57BL/6J samples as controls at the appropriate age, and confirmed minimal detectable differences between these samples and littermate control samples. We did not collect heterozygous control littermates for Trpm8 mice, and instead used same-age C57BL/6J samples as controls. Plots were generated using the ggplot2 R package (RRID:SCR_014601).

sexDEG analysis

To determine DEGs between sexes, we performed sample-pseudobulk-based DESeq2 (RRID:SCR_015687) differential expression testing for each cell type. After removing mitochondrial, ribosomal, Y chromosome and X inactivation genes, we split the dataset by ages. Then, we aggregated raw counts from cells of the same sample to use as input for DESeq2 and shrunk the log2 fold changes using lfcShrink (type = ‘apeglm’) to generate lists of DEGs between either male and female samples (sexDEGs). DEGs with adjusted P value less than 0.05 were considered significant and used for downstream analysis. To increase our n number, we included control samples from mutant–control experiments. For GO term analysis we used gprofiler2 in R.

Augur classifier analysis

To identify which cell types have a notable change in expression between the control and mutant conditions, we used the package Augur v.1.0.3 (RRID:SCR_023964)87, which performs cross-validated random-forest classifier analysis of single-cell datasets. First, we split the dataset by age and removed mitochondrial and ribosomal genes. Then we applied Augur (var_quantile=0.9, subsample_size=20) to generate area under the curve scores. For this analysis, control data included only control littermates with no added C57BL/6J samples (except for Trpm8 mutants, where C57BL/6J samples were the only available controls).

Pseudotime analysis of Trpc2 mutant and control datasets

For each cell type, pseudotime was calculated across all ages from C57BL/6J data using Slingshot60 on log-normalized gene expression data and the top 20 principal components calculated from 2,000 variable features. Then, for each mutant or control Trpc2 sample, cells from that sample were projected into the C57BL/6J 20-PC space (using stats::predict) and Slingshot prediction was performed (using slingshot::predict) to give each cell a predicted pseudotime value. Pseudotime values were averaged across all cells within each sample, and then between samples, to give data shown in Fig. 5c. Two-sided t-test was performed to calculate P value between control and mutant cell type pseudotime values.

Shared neuronal maturation gene expression

To identify a set of genes that increase across age in all neuronal types, we first created a Seurat object with equal numbers of cells from each cell type by randomly selecting ten cells of each cell type at E16/E18 or at P65. Then, we used Seurat’s FindMarkers to identify genes that were more highly expressed among P65 cells than E16/E18 cells. From this list, we selected genes with average log2-transformed fold change greater than 0.5 that were expressed in at least 30% of P65 cells (pct.1 > 0.3). This yielded a list of 243 genes. We used Seurat’s AddModuleScore with this list of genes for the entire C57BL/6J dataset and found that the module score for these genes increased across age in every cell type (data not shown separately for each cell type; data shown altogether in Fig. 5d, left, underlying data are averaged within a cell type). We then used Seurat’s AddModuleScore with this gene set on Trpc2−/+ or Trpc2−/− cells and averaged the values within a cell type (Fig. 5d, right).

snATAC-seq analysis

snATAC-seq profiles were filtered to include only nuclei with at least 500 fragments, and only nuclei with paired snRNA-seq profiles passing quality control as described above. C57BL/6J samples were split into two replicates, with each replicate containing one male and one female sample at each age. Peaks were called for each cell type in each replicate using macs2 (ref. 88) callpeak command with parameters ‘–shift -100 –extsize 200 –nomodel –callsummits –nolambda –keep-dup all -q 0.05’. Only reproducible peaks that are present in both replicates were kept (n = 778,573 peaks). Finally, to compile a union peak set, we combined peaks from all cell types and extended the peak summits by 200 bp on either side. Overlapping peaks were then handled using an iterative removal procedure. First, the most significant peak, that is, the peak with the smallest P value, was kept and any peak that directly overlapped with it was removed. Then, this process was iterated to the next most significant peak and so on until all peaks were either kept or removed due to direct overlap with a more significant peak. Differentially accessible peaks were identified using the getMarkerFeatures() function from the ArchR89 package using a Wilcoxon rank sum test and accounting for bias introduced by TSSEnrichment and log10(nFrags). Peaks with FDR ≤ 0.1 and log2 fold change greater than or equal to 0.25 were considered cell type-specific. Known transcription factor binding motifs present in the ‘vierstra’ motifset were assigned to differentially accessible genomic regions and motif enrichment was evaluated using a hypergeometic test implemented by the peakAnnoEnrichment() function. Enriched motifs were those with minimum P adjusted enrichment of 20, top three shown per cell type (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Motif footprints were calculated by combining all peaks harbouring a given motif in aggregate and accounting for Tn5 insertion bias using the the getFootprints() function.

Viral injections and immunohistochemistry

To visualize synaptic puncta in Gal+ or Opn5+ neurons, we injected 200 nl of AAV2/9-hSyn-FLEx-loxP-Synaptophysin-mGreenLantern-T2A-GAP43-mScarlet (provided by L. Schwarz; details of its construction can be found in ref. 90) at a titre of 4.9 × 1012 into the POA of P0 Gal-cre or Opn5-cre pups (Gal–cre: 2.15 mm anterior to lambda; 0.25 mm right of the midline; 3.9 mm deep; Opn5-Cre: 2.4 mm anterior to lambda; 0.1 mm right of the midline; 4.25 mm deep). Animals were perfused at P10 with PBS followed by 4% PFA after deep anaesthesia by isoflurane. Brains were dissected out and placed in 4% PFA for 1–2 nights, then vibratome sectioned at 60 μm. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) immunofluorescence was used to amplify Synaptophysin-mGreenLantern signal, along with VIP antibody staining. Floating coronal sections were washed three times (5 min each time) in 1× PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBST), then blocked for 1 h in Animal Free Blocker 5× Concentrate (Vector Laboratories) diluted to 1× in PBST. All washes and blocking were performed at room temperature with gentle shaking at 100 rpm. Sections were then placed in blocking solution with primary antibodies (GFP: 1:1,000 dilution, Aves Laboratories, RRID:AB_2307313; VIP: 1:1,000 dilution, Abcam) and left overnight with gentle shaking at 4 °C. Sections were again washed three times for 5 min each in PBST, then incubated in blocking solution with secondary antibodies (1:1,000 dilutions of (1) goat anti-chicken IgY, AlexaFluor 488 conjugate, Jackson ImmunoResearch, RRID:AB_2337390 and (2) goat anti-rabbit IgG, AlexaFluor 647 conjugate, Jackson ImmunoResearch, RRID:AB_2338072) for 2 h. Following three more washes as before, sections were mounted using prolong gold and kept at room temperature for at least one night before imaging. Sections were imaged at ×10 or ×40 using either a Zeiss Axio Imager.Z2 at ×40 or Zeiss LSM900 Confocal Microscope.

RNA in situ hybridization

Double- and triple-label fluorescence in situ hybridization experiments were performed using the RNAscope Assay V2 kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics). Brains were harvested and frozen in optimal cutting temperature medium, then sliced on the cryostat (P18+, 16 μm; P0–P10, 18 μm; E18, 14 μm). The RNAscope Assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with one exception: For E18 brains, protease treatment was restricted to 10 min at room temperature, compared to 30 min at room temperature for all other ages. Slides were imaged on an Axio Scan.Z7 microscope at ×20.

Behaviour assays

For all behaviour tests, litters were obtained by crossing Trpc2−/+ females with Trpc2−/− males, and removing males after 2 weeks cohabitation, so that litters were born with only mothers present. Pups were toe-clipped at P7 for identification and genotyping for Trpc2 and sex. All assays were blinded for both experiment and behaviour scoring, with pups split into group 1 or group 2, with random assignment of group to genotype. All assays were performed during the first 6 h of the dark cycle under dim red light.

Maternal retrieval

Assays were performed when pups were P9–P10. 1–2 pups of each genotype were removed from the litter and placed in a fresh cage. Then, one Trpc2−/− and one Trpc2−/+ pup, both of the same sex, were selected and simultaneously placed in two corners of the cage opposite the nest, where the mother typically went when the cage lid was lifted. Experiments were balanced such that pups from each genotype were placed in the corner slightly closer to the nest at equal levels. Assays were video recorded and retrieval latency was manually scored (blinded to genotype) for each pup as the time for the mother to grab a pup, return it to the nest and release it from her mouth (Extended Data Fig. 10g).

Maternal approach

Assays were performed when pups were P13–P14, following a 30-min isolation period at room temperature (described below, Isolation vocalizations). Mothers were anaesthetized with ketamine–xylazine mix (10 mg ml−1 ketamine and 1 mg ml−1 xylazine) and placed on her side in one corner of the cage. A pup was then introduced 15 cm away from the mother’s abdomen, and facing the mother. Time to first contact between pup and any part of the mother was scored manually (blinded to genotype) (Extended Data Fig. 10h).

Littermate approach and behavioural quiescence

Assays were performed when pups were P11–P12. Two to four pups, all of the same genotype, were placed in a fresh cage, one by one, at 3-min intervals, at 10 cm apart from one another. Typically, pups of this age will spend a brief time moving around the cage, before entering a prolonged period of behavioural quiescence. When another pup is added to the cage, pups often encounter one another, huddle together and stop moving. We manually scored (blinded to genotype) both time to first contact of a littermate (Extended Data Fig. 10i) and time to enter behavioural quiescence (Extended Data Fig. 10j).

Isolation vocalizations

P13–P14 pups were placed individually in fresh cages and recorded with ultrasonic microphones (u256, Batsound) embedded in cage lids, for 30 min. We used the AVA package91 (https://autoencoded-vocal-analysis.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html) along with custom Python scripts to perform amplitude-based ultrasonic vocalization segmentation. On P14, pups were tested with a heating pad (Small Animal Heated Pad, K&H) underneath the cage, with all cage bottom material removed. Infrared gun temperature measurements of the cage floor consistently showed 33.3–36.7 °C (heating pad) or 21.7–23.9 °C.

Statistics and reproducibility

Data were processed and analysed using a combination of R and Python codes. Sample sizes were chosen based on common practice in single-nucleus sequencing experiments. Individual data points were plotted wherever possible. Boxplots represent the median, first and third quartiles (hinges) and 1.5× interquartile range (whiskers). Outliers are shown wherever individual data points are not plotted. All data were analysed using two-tailed non-parametric tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 and ***P < 0.0001. Statistical details are given in the respective figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.