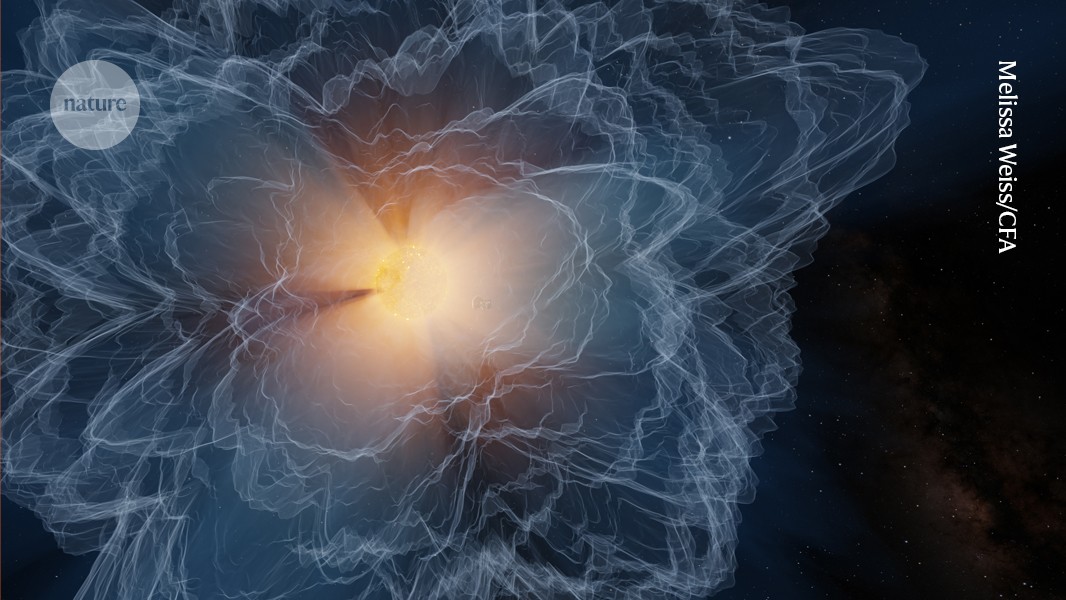

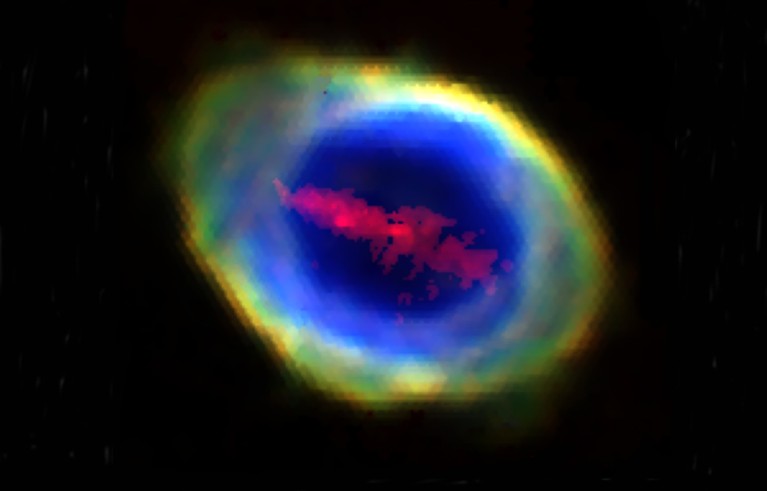

Puffed-up Sun. Data from inside the Sun’s corona — the outermost layer of its atmosphere — helped astrophysicists to create a sharper picture of the Sun’s shifting boundaries than ever before. The corona’s outer edge, depicted in this illustration, has a rough, spiky shape that expands and contracts like a pufferfish as the Sun becomes more or less active. The research could help scientists to better predict how solar activity affects Earth’s magnetic field, satellites, human health and atmospheric effects such as auroras.

Credit: Yoshinari Sasaki

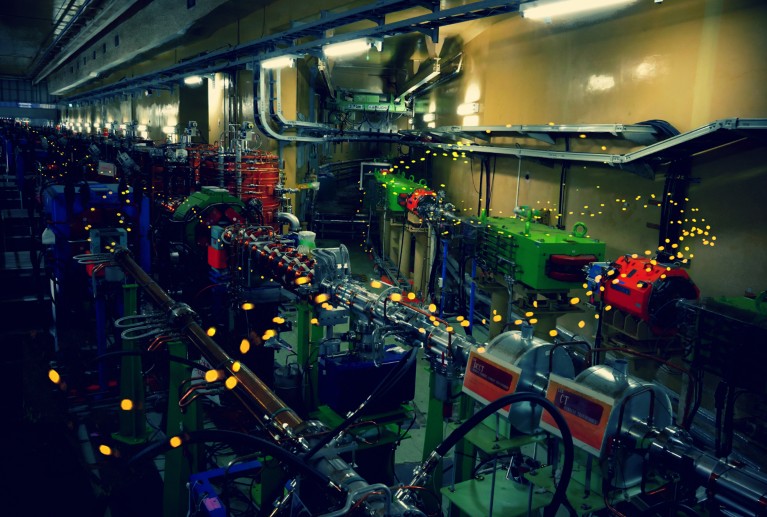

Physics wonders. This photo of a firefly making its way around a particle accelerator was created as a composite image. “Watching its glowing paths is like seeing the streaks of charged particles in a spark chamber or a Cherenkov detector — beautiful, fleeting and absolutely mesmerizing,” says Yoshinari Sasaki, whose shot was among this year’s crop of nominees for the Global Physics Photowalk 2025. The judges commended the photograph’s composition in blending particle physics with Japanese nature.

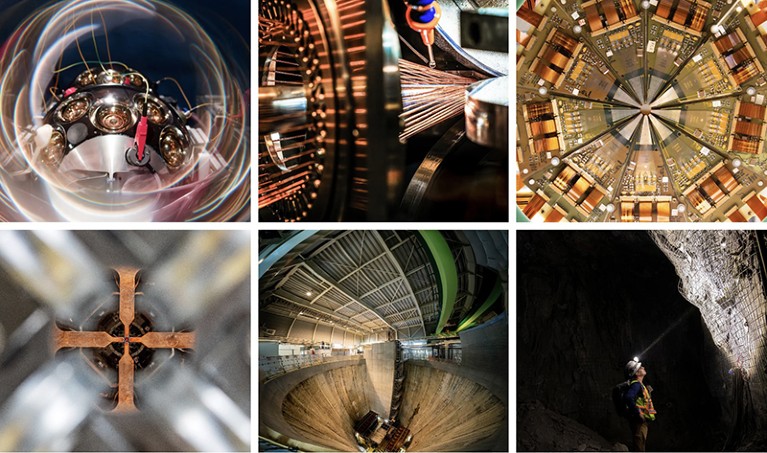

Credit (clockwise from top left): Justine Coustrain-Jean/CPPM/CNRS, Erik Kuna, Andrea Giulian, Adam Tomjack, Suganuma Hisahiro, Antonio Giannicola Colangiulo.

Other entries include a shot of a physicist working at a deep excavation site for an underground research facility aiming to house future generations of science, and an image of equipment in the superconducting laboratory at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics lab in Geneva, Switzerland. The winners will be announced on 12 February.

Credit: Tori Harp/Capture the Atlas

Below the aurora. Solar storms in January have been the largest in 20 years. Coronal mass ejections and solar flares released charged particles that bombarded Earth’s magnetic field, creating spectacular auroras. Southern Lights reached as far north as New Zealand, seen here as a backdrop to this abseiler’s decent into an ice cave in South Island’s Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park. Northern Lights were also seen as far south as the United Kingdom, Germany and the United States.

Credit: Maxime Aubert

Humanity’s handprint. This stencilled outline of a hand might be the world’s oldest known rock art. The painting, found on the Indonesian island of Muna, Sulawesi, dates back to at least 67,800 years ago. The stencil pre-dates archaeologists’ previous rock-art discoveries in the same region by roughly 15,000 years, suggesting that Homo sapiens reached the Australia–New Guinea landmass earlier than previous research had shown. The hunting scenes are more recent, suggesting that humans have visited the cave over thousands of generations.

Credit: Shuntaro Yamada & Kateřina Holomková

Credit: Shuntaro Yamada & Kateřina Holomková

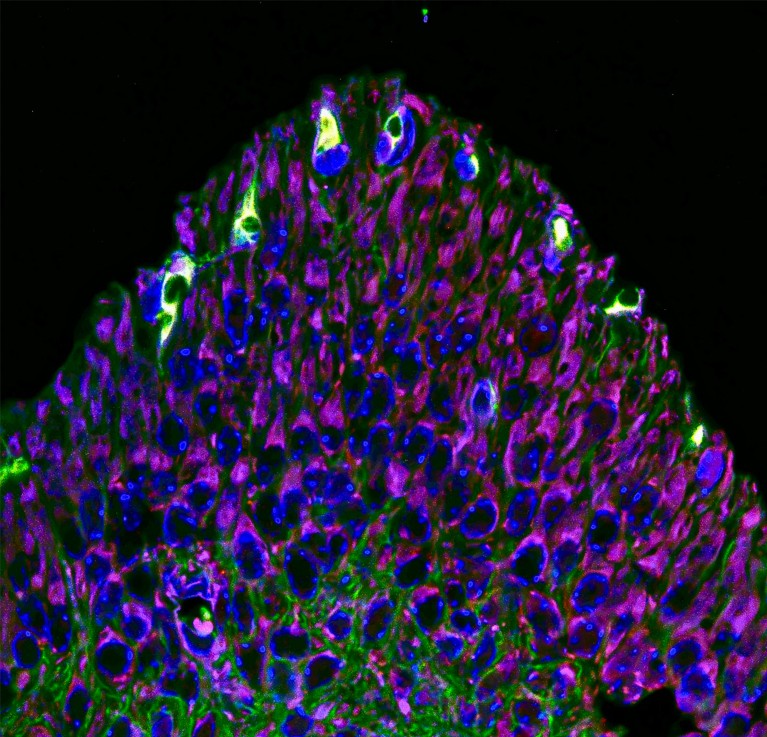

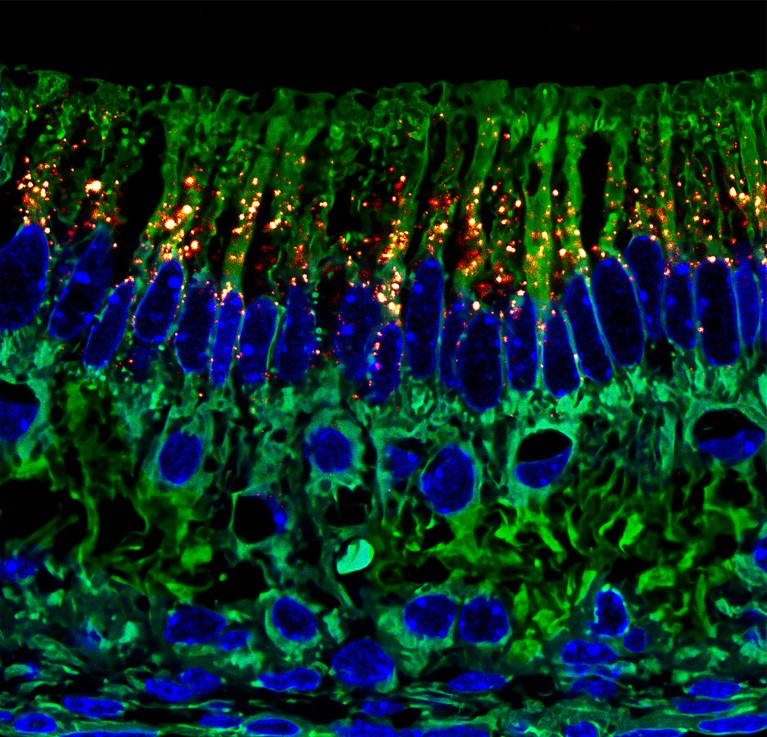

Bio-tooth. These are ameloblasts — specialized epithelial cells crucial for the formation of tooth enamel. The cells secrete an enamel matrix that mineralizes over time to become as hard as stainless steel. Ameloblasts disappear once the layer has formed, making enamel impossible to repair. This image shows sensory cells called odontoblasts inside the dental pulp. These cells enable the teeth to detect sensations of cold and touch, and form new dentin layers when needed. “Researchers including myself utilize oral-derived stem cells to achieve tooth regeneration, including whole tooth regeneration or replacement, or what we call bio-tooth,” says Shuntaro Yamada, a stem-cell biologist at the University of Bergen, Norway, who took the images.

Credit: R. Wesson, Cardiff University/UCL