A broad experimental programme has shown that the three quantum-mechanical eigenstates of neutrino flavour, νe, νμ and ντ, are related to the three eigenstates of neutrino mass, ν1, ν2 and ν3, by the unitary Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata (PMNS) matrix11,12. This mixing between flavour and mass states gives rise to the phenomenon of neutrino oscillation, in which neutrinos transition between flavour eigenstates with a characteristic wavelength in \(L/{E}_{\nu }\propto {(\Delta {m}_{ji}^{2})}^{-1}\), where L is the distance travelled by the neutrino, Eν is the neutrino energy and \(\Delta {m}_{ji}^{2}={m}_{j}^{2}-{m}_{i}^{2}\) is the difference between the squared masses of the mass eigenstates νi and νj. The three known neutrino mass states give rise to two independent mass-squared differences and thus to two characteristic oscillation frequencies that have been well measured with neutrinos from nuclear reactors13,14, the Sun15, the atmosphere of Earth16,17 and particle accelerators18,19,20.

In apparent conflict with the three-neutrino model, several experiments during the past three decades have made observations that can be interpreted as neutrino flavour change with a wavelength much shorter than is possible given only the two measured mass-squared differences3,4,5,6,7,8,9. These observations are often explained as neutrino oscillations caused by at least one additional mass state, ν4, corresponding to a mass-squared splitting of \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}\gtrsim 1{0}^{-2}\,{{\rm{eV}}}^{2}\), which is much greater than the measured \(\Delta {m}_{21}^{2}\) and \(\Delta {m}_{32}^{2}\). New mass states would require the addition of an equivalent number of new flavour states, in conflict with measurements of the Z-boson decay width21, which have definitively shown that only three light neutrino flavour states couple to the Z boson of the weak interaction. Therefore, these additional neutrino flavour states must be unable to interact through the weak interaction and are thus referred to as ‘sterile’ neutrinos. In this analysis, we focus specifically on light sterile neutrinos—those with masses below at least half the mass of the Z boson. It should be noted that the term ‘sterile neutrino’ has also been used to describe new particles, such as heavy right-handed lepton partners, that are potentially more massive than the Z boson. However, our study does not directly test these scenarios. The discovery of additional neutrino states would have profound implications across particle physics and cosmology, for example, on our understanding of the origin of neutrino mass, the nature of dark matter and the number of relativistic degrees of freedom in the early universe.

With the addition of a single new mass state ν4 and a single sterile flavour state νs, the PMNS matrix becomes a 4 × 4 unitary matrix described by six real mixing angles θij (1 ≤ i < j ≤ 4). Oscillations driven by the two measured mass-squared splittings have not had time to evolve for small values of L/Eν. The νμ to νe flavour-change probability, \({P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}}\), and the νe and νμ survival probabilities, \({P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}}\) and \({P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{mu}}}}\), can then, to a very good approximation, be described by

$${P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}}={\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}}){\sin }^{2}\left(\frac{\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}L}{4{E}_{\nu }}\right),$$

(1)

$${P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}}=1-{\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{ee}}}){\sin }^{2}\left(\frac{\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}L}{4{E}_{\nu }}\right),$$

(2)

$${P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}}=1-{\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu \mu }}}){\sin }^{2}\left(\frac{\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}L}{4{E}_{\nu }}\right),$$

(3)

where θee ≡ θ14, \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu \mu }}})\equiv 4{\cos }^{2}{\theta }_{14}{\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{24}(1-{\cos }^{2}{\theta }_{14}{\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{24})\) and \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})\equiv {\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{14}){\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{24}\), following the common parameterization22. Flavour transitions due to these new oscillation parameters are experimentally probed by observing unexpected deficits or excesses in charged current (CC) νe and νμ interactions in a flavour-sensitive neutrino detector from a source of well-defined neutrino flavour content.

Observations compatible with a fourth neutrino mass state have been made in measurements of intense electron-capture decay sources6,7,8, in which a deficit in detected νe rates implies non-unity \({P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}}\) from a \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2} > {\mathcal{O}}(1\,{{\rm{eV}}}^{2})\). Although a hint of non-unity \({P}_{{\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{e}}}\to {\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{e}}}}\) is provided by the nuclear-reactor-based Neutrino-4 experiment9, this result is in conflict with other reactor-based observations from DANSS, NEOS, PROSPECT and STEREO, which see no evidence for L/Eν-dependent \({\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{e}}}\) disappearance23,24,25,26. Two accelerator-based experiments, LSND and MiniBooNE, have observed potential evidence of non-zero \({P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}}\) associated with large mass splittings of \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2} > {\mathcal{O}}(1{0}^{-2}\,{{\rm{e}}{\rm{V}}}^{2})\). The LSND experiment observed an anomalous excess of \({\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{e}}}\) interactions in a π+ decay-at-rest beam3. The MiniBooNE experiment, situated downstream from the Booster Neutrino Beam (BNB) proton target facility generating a beam of GeV-scale νμ and \({\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{\mu }}}\) from decays of boosted π+ and π−, observed an excess of electromagnetic showers indicative of νe interactions that would imply a non-zero \({P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}}\) (refs. 4,5). Observations of νe disappearance and νe appearance should be accompanied by νμ disappearance (non-unity \({P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}}\)) if the PMNS matrix is unitary. No conclusive observation of this νμ disappearance has been reported27,28,29. The overall picture of the existence and phenomenology of sterile neutrino states thus remains inconclusive.

In this article, we present new results on sterile neutrino oscillations from the MicroBooNE liquid-argon time projection chamber (LArTPC) experiment at Fermilab10. Situated along the same BNB beamline hosting the MiniBooNE experiment, MicroBooNE was conceived to directly test the non-zero \({P}_{{\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}\to {\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}}\) observation of MiniBooNE. By supplanting the Cherenkov detection technology of MiniBooNE with the precise imaging and calorimetric capabilities of a LArTPC, MicroBooNE can reduce backgrounds and select a high-purity sample of true νe-generated final-state electrons. The first νe measurement results of MicroBooNE using differing final-state topologies showed no evidence for an excess of νe-generated electrons from the BNB30,31,32,33. These results were used to set limits on νμ → νe flavour transitions, excluding sections of the region in \((\Delta {m}_{41}^{2},{\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}}))\) space favoured by LSND and MiniBooNE data34. As the BNB has an intrinsic contamination of electron neutrinos, the disappearance of electron neutrinos can cancel the appearance of electron neutrinos from νμ → νe oscillations35. This effect leads to a degeneracy between the impact of the mixing angles θμe and θee of equations (1) and (2) that weakens the sensitivity to the parameters of the expanded 4 × 4 PMNS matrix.

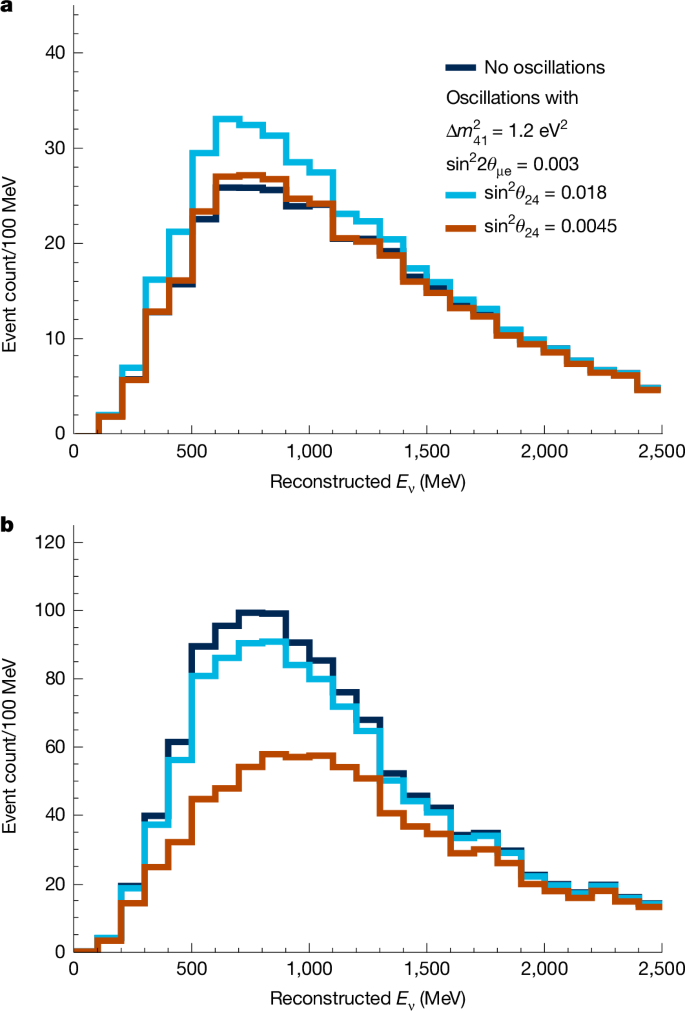

We overcome the limitations of the degeneracy between νe appearance and νe disappearance by performing one of the first oscillation searches using two accelerator neutrino beams: the BNB and the Neutrinos at the Main Injector (NuMI) beam. The MicroBooNE detector is aligned with the direction of BNB and is at an angle of about 8° relative to the NuMI beam. Beam timing information is used to distinguish and record events from each beam separately. This configuration results in two neutrino datasets differing in the intrinsic electron-flavour fraction. The electron-flavour content of BNB is 0.57% and that of the NuMI beam is 4.6%. These two independent sets of data, with substantially different electron-flavour contents, break the degeneracy between νe appearance and disappearance. We show the impact of using two beams in Fig. 1a,b, in which we compare simulated νe energy spectra from the BNB and the NuMI beam for the three-flavour (3ν) hypothesis and for two sets of parameters of the expanded four-flavour (4ν) PMNS model with \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}=1.2\,{{\rm{e}}{\rm{V}}}^{2}\) and \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})=0.003\). For \({\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{24}=0.0045\) the νe appearance and disappearance cancel in the BNB, leaving a νe spectrum that is almost identical to the 3ν case, whereas the NuMI beam shows an indication of νe disappearance. The appearance and disappearance effects almost fully cancel in the NuMI beam for \({\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{24}=0.018\), whereas the BNB shows a clear indication of νe appearance. In the Methods, we provide further discussion of this degeneracy over a broader range of mass-squared splittings and mixing angles.

a,b, Simulated reconstructed energy spectra of FC CC νe interactions in MicroBooNE from the BNB (a) and the NuMI beam (b). The dark blue histograms show the 3ν expectation for \({\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{24}={\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})=0\). The light blue and red histograms show expectations for two sets of parameters of the 4ν model, both with \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}=1.2\,{{\rm{e}}{\rm{V}}}^{2}\) and \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})=0.003\). The light blue histograms show the expectation for \({\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{24}=0.018\) and the red histograms show the expectation for \({\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{24}=0.0045\). Note that these parameters were chosen specifically to highlight differences in the oscillated spectra between BNB and NuMI and do not imply that parameter spaces associated with these values are newly excluded by this result.

Using the two-beam technique, this new MicroBooNE analysis achieves marked improvements in sensitivity to the parameters \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{ee}}})\) and \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})\) relative to MicroBooNE’s prior sterile neutrino analysis over a broad range of \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}\) values. These improvements are shown by the sensitivities presented in Extended Data Fig. 2. The results presented here using two neutrino beams place robust new constraints on the validity of the sterile neutrino hypothesis in explaining existing short-baseline anomalies in neutrino physics. This analysis strengthens the direct test of the sterile neutrino interpretation of the MiniBooNE anomaly and allows MicroBooNE to probe the \({\sin }^{2}(2{{\theta }}_{{\rm{\mu }}{\rm{e}}})\) parameter space favoured by LSND. We also constrain \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{ee}}})\), complementing existing exclusions from reactor, solar36,37 and β-decay38 experiments, thereby further restricting the sterile neutrino parameter space relevant to the gallium anomaly.

We use data corresponding to 6.369 × 1020 protons on target (POT) in the BNB, with magnetic van der Meer horns configured to focus positively charged hadrons, leading to a νμ-dominated beam with a 5.9% \({\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{\mu }}}\) component and a 0.57% \({\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}+{\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{e}}}\) component. From the NuMI beam, a total of 10.54 × 1020 POT are used, in which 30.8% were taken with horns configured to focus positively charged hadrons and the remainder with horns focusing negatively charged hadrons. The NuMI flux observed in the MicroBooNE detector, with both horn configurations combined, is νμ dominated with a 42.1% \({\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{\mu }}}\) component and a 4.6% \({\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}+{\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{e}}}\) component. In the rest of this paper, we do not discriminate between neutrinos and antineutrinos and refer to the \({\nu }_{{\rm{\mu }}}+{\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{\mu }}}\) and \({\nu }_{{\rm{e}}}+{\overline{\nu }}_{{\rm{e}}}\) samples as νμ and νe samples for brevity. For both BNB and NuMI, the POT used in this analysis represent roughly half of the total data collected by the MicroBooNE detector; additional data remain available for future studies.

The LArTPC detector of MicroBooNE has an active volume of 10.4 × 2.6 × 2.3 m3 containing 85 tonnes of liquid argon. Charged particles passing through the argon create ionization trails. A 273 V cm−1 electric field drifts the ionization electrons towards an anode plane consisting of three layers of wires separated by 3 mm and each with a 3-mm wire pitch that collects the electrons and enables three-dimensional imaging of the neutrino interactions. The passage of charged particles through the argon also produces scintillation light that is collected by a system of photomultiplier tubes to provide timing information. Signal processing and calibrations of MicroBooNE data are described in refs. 39,40,41,42,43,44.

Neutrino interactions in the LArTPC are reconstructed with the Wire-Cell analysis framework45. The techniques for identifying and reconstructing neutrino interactions and their energies have been described elsewhere33. We select a sample of CC νe interactions from the BNB (NuMI beam) with 82% (91%) purity and 46% (42%) efficiency, and a sample of CC νμ interactions with 92% (78%) purity and 68% (62%) efficiency. The CC νe and CC νμ samples are divided into fully contained (FC) and partially contained (PC) samples, depending on whether all charge depositions are contained in a fiducial volume 3 cm within the TPC boundary. The CC νμ events that contain a reconstructed π0 are separated into two additional FC and PC samples per beam. Neutral current (NC) interactions that produce a π0 are distinguished by the absence of a long muon-like track and the presence of detached reconstructed electromagnetic showers. These form an additional sample. In total, we define 14 distinct event categories, seven for each beam.

We produce a Monte Carlo prediction of our 14 samples, to which we compare the data. There is substantial systematic uncertainty creating this Monte Carlo simulation. The uncertainty on the predicted rates of the 14 samples is given in Table 1 and is referred to as the unconstrained systematic uncertainty. The largest uncertainties come from neutrino interaction modelling for the BNB samples and from a combination of neutrino flux and interaction uncertainties for the NuMI samples. Many of these uncertainties are highly correlated. Thus, a combined fit of all samples effectively constrains the uncertainties on the CC νe prediction and at the same time allows the CC νe prediction to be modified, as can be seen from Table 1. The pionless samples constrain uncertainties on CC νe signal events, whereas the π0 samples constrain uncertainties on the dominant background.

Uncertainties on the neutrino flux prediction arise from uncertainties in the production of charged pions and kaons in the BNB and NuMI targets and the material around the target halls and hadron-decay volumes. These uncertainties are evaluated through comparison with external hadron production data46,47,48, following a procedure similar to that described in ref. 49. The νe flux from three-body K and μ decays is highly correlated with the νμ flux from two-body π and K decays, allowing our νμ samples to effectively constrain the uncertainties on the νe flux predictions. The neutrino interaction model is tuned using datasets of pionless CC interactions from the T2K experiment50. Uncertainties on this neutrino interaction model are evaluated by varying the input parameters within their allowed uncertainties. These uncertainties are correlated between the BNB and NuMI datasets and between the CC νμ and νe samples because of the lepton universality of the weak interaction. Uncertainties on the simulation of the detector include uncertainties on the response of the detector to ionization, uncertainties on the amount of ionization charge freed by passing charged particles through the detector, uncertainties on the electric field map of the TPC, uncertainties on the production and propagation of scintillation light, uncertainties on backgrounds from interactions occurring outside the cryostat, and uncertainties on finite statistics of the simulation samples used for predictions.

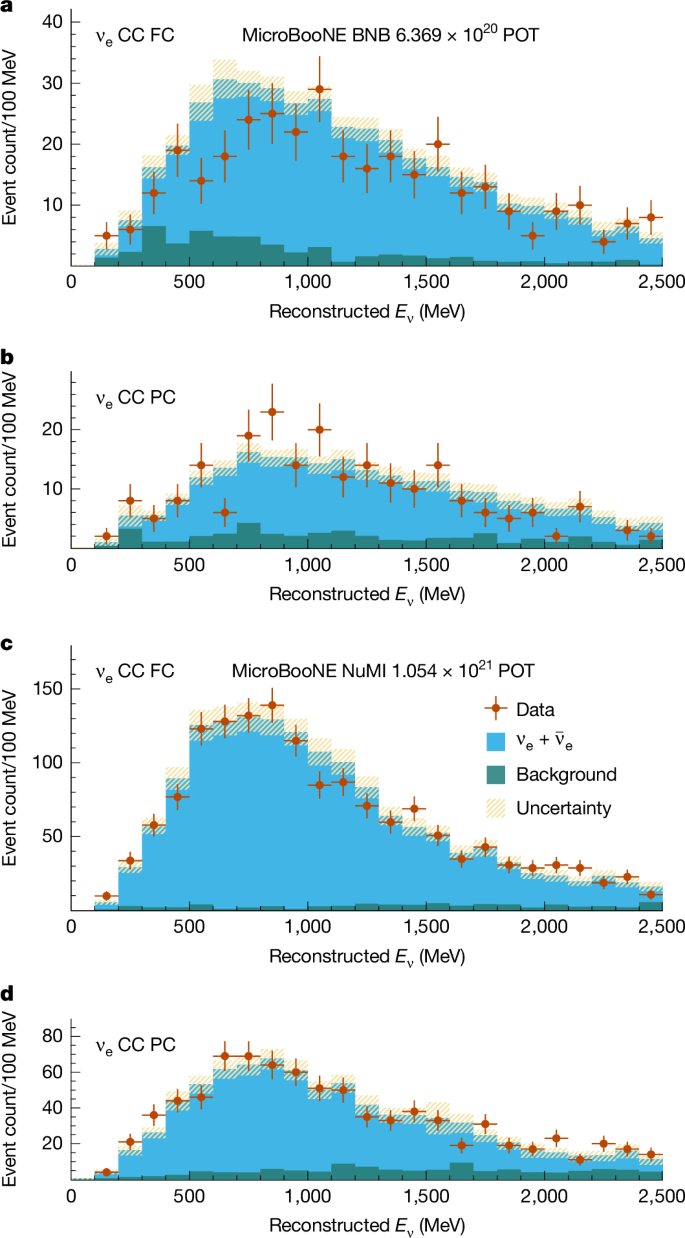

The simultaneous fit to the 14 samples from the BNB and the NuMI beam incorporates all sources of systematic uncertainty through a covariance matrix. We allow \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})\), \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{ee}}})\) and \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}\) complete freedom within unitarity bounds as parameters of the fit. The covariance-matrix formalism χ2 test of the fit can be found in the Methods. The constrained predictions shown in Fig. 2 assume the 3ν hypothesis of \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})={\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{ee}}})=0\). They agree well with the data, with a P-value of 0.92. The best-fit values for the oscillation parameters in the 4ν hypothesis are \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}=1.30\times 1{0}^{-2}\,{{\rm{e}}{\rm{V}}}^{2}\), \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})=0.999\), and \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{ee}}})=0.999\), with a χ2 difference with respect to the 3ν hypothesis of

$$\Delta {\chi }^{2}={\chi }_{{\rm{null}},3\nu }^{2}-{\chi }_{\min ,4\nu }^{2}=0.228.$$

(4)

We observe no marked preference for the existence of a sterile neutrino with a P-value of 0.96 evaluated using the Feldman–Cousins procedure.

a–d, Reconstructed energy spectra of events selected as FC CC νe candidates in the BNB (a), PC CC νe candidates in the BNB (b), FC νe candidates in the NuMI beam (c) and PC νe candidates in the NuMI beam (d). The data points are shown with statistical error bars. The constrained predictions for each sample are shown for the 3ν hypothesis as the solid histograms, with the blue showing the true CC νe events and the green showing the background events. The background category contains CC νμ interactions, NC neutrino interactions, cosmic rays and interactions occurring outside the fiducial volume of the detector. The yellow band shows the total constrained systematic uncertainty on the prediction.

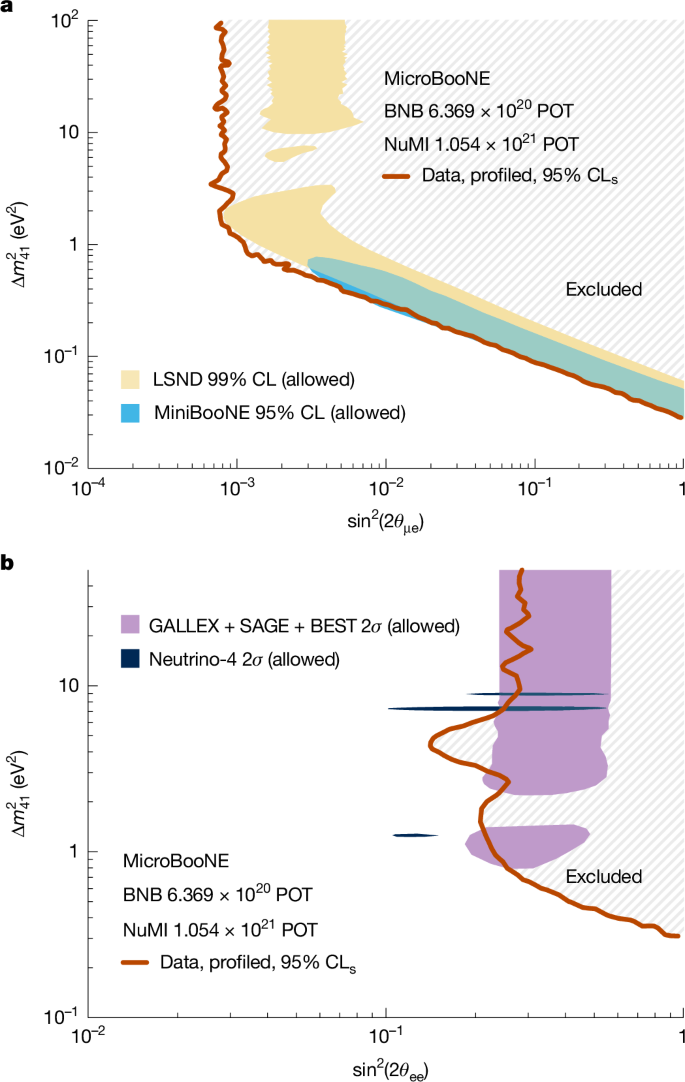

Exclusion contours are calculated using the frequentist CLs (confidence level as a function of s) method51. The exclusion contour in any two-dimensional parameter space is obtained by profiling the third free parameter. At any point in the two-dimensional space, the value of the profiled parameter that minimizes the χ2 with respect to the data is chosen. Figure 3a shows the 95% CLs exclusion contour in the \((\Delta {m}_{41}^{2},{\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}}))\) parameter space. The region allowed at 99% CL by the LSND measurement and the vast majority of the region allowed at the 95% CL by the MiniBooNE experiment are excluded. Figure 3b shows the 95% CLs exclusion contour in the \((\Delta {m}_{41}^{2},{\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{ee}}}))\) parameter space. A notable portion of the region allowed by gallium measurements and part of the region derived from the Neutrino-4 measurement are excluded. In the Methods and Extended Data Fig. 2, we compare our exclusions with the expected median sensitivities.

a,b, The red lines show exclusion limits at the 95% CLs level in the plane of \(\Delta {m}_{41}^{2}\) and \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu }}{\rm{e}}})\) (a) or \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{e}}})\) (b). All the regions to the right of these lines are excluded by the MicroBooNE data. In a, the yellow shaded area is the LSND 99% CL allowed regions3, which neglects the degeneracy between νe disappearance and appearance. The light blue area is the MiniBooNE 95% CL allowed region58, considering both νe disappearance and appearance. In b, the purple shaded area is the 2σ allowed region of the gallium anomaly59. The dark blue shaded area is the 2σ allowed region from the Neutrino-4 experiment9. For context, note that the stronger-than-expected constraint on \({\sin }^{2}(2{\theta }_{{\rm{\mu e}}})\), driven by the deficit observed in the BNB νe CC FC sample and the excess in the NuMI νμ CC sample, is discussed in detail in the Methods and Extended Data Fig. 2.

In summary, using data from the MicroBooNE detector, we report one of the first searches for a sterile neutrino using two accelerator neutrino beams. The oscillation fit to the 4ν model using a total of 14 CC νe, CC νμ and NC π0 samples from the BNB and the NuMI beam in a single detector achieves a marked reduction of systematic uncertainties and a powerful mitigation of degeneracies between νe appearance and disappearance. The result shows no evidence of oscillations induced by a single sterile neutrino and is consistent with the 3ν hypothesis with a P-value of 0.96. We comprehensively exclude at a 95% CL the 4ν parameter space that would explain the LSND and MiniBooNE anomalies through the existence of a light sterile neutrino in a model with an extended 4 × 4 PMNS matrix. Our result expands the diverse range of experimental approaches, excluding regions that would explain the gallium anomaly and the Neutrino-4 observation with a light sterile neutrino. This work, therefore, provides a robust exclusion of a single light sterile neutrino as an explanation for the array of short-baseline neutrino anomalies observed over the past three decades, representing the strongest constraint from a short-baseline experiment using accelerator-produced neutrinos. Expanded models, including several light sterile neutrinos52, neutrino decay effects53,54 or production and decay of new particles connected with the dark sector55,56 might explain the anomalies. The Short Baseline Neutrino (SBN) Programme57 at Fermilab adds two new LArTPC detectors in the BNB, at different distances from the proton target. Future measurements by MicroBooNE and the broader SBN Programme can shed light on this expanded model space, with future comprehensive insights provided by near-term short-baseline measurements from diverse flavour channels and energy regimes.