Taking a risk by opening the door to a new research field can have negative consequences for scientists, at least in the short term, a study shows.Credit: Dwayne Senior/Bloomberg via Getty

Shifting to a different research field can have negative consequences for a scientist, according to an analysis1. A team assessed millions of scientific papers and concluded that, when a scientist moves away from their original area of expertise, their publications receive fewer citations than their previous work. The larger the shift, the greater the effect — a phenomenon the authors of the study have named the ‘pivot penalty’.

Renewal of NIH grants linked to more innovative results, study finds

The study, published today in Nature, also investigates cases in which an external event — such as a disease outbreak — drives the shift in focus. The findings suggest the potential consequences of the recent US research-funding cuts — targeted at research topics including misinformation and the health of minority groups — that could push scientists to change fields.

“When you move out of the area in which you’re trusted, you lose that recognition,” says Kieron Flanagan, a science-policy specialist at the University of Manchester, UK, adding that he is not surprised by the results of the analysis. But the sheer amount of data that the team evaluated sets the study apart, he says.

“I hadn’t seen an analysis of that particular issue done at that scale,” says James Wilsdon, director of the Research on Research Institute in London.

Quantifying the pivot

The authors measured scientific pivots by scrutinizing the reference sections of 25.8 million research papers published between 1970 and 2015. They compared the citations in a paper with those cited by the same author in the previous three years; specifically, they analysed the journals in which the cited papers were published.

Given that journals are mostly topic-specific, this shows the scientific fields that a researcher typically draws from, says Dashun Wang, a computational social scientist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and a co-author of the study. “If all of a sudden, I’m citing journals that I’ve never cited, it’s an indication that I’m doing something very different than what I usually do,” Wang says.

According to the analysis, a pivot is large if, for instance, a researcher moves from crime-data assessment to forecasting the spread of COVID-19. On the other hand, a small pivot would be moving from research on bat-derived influenza viruses to studying the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.

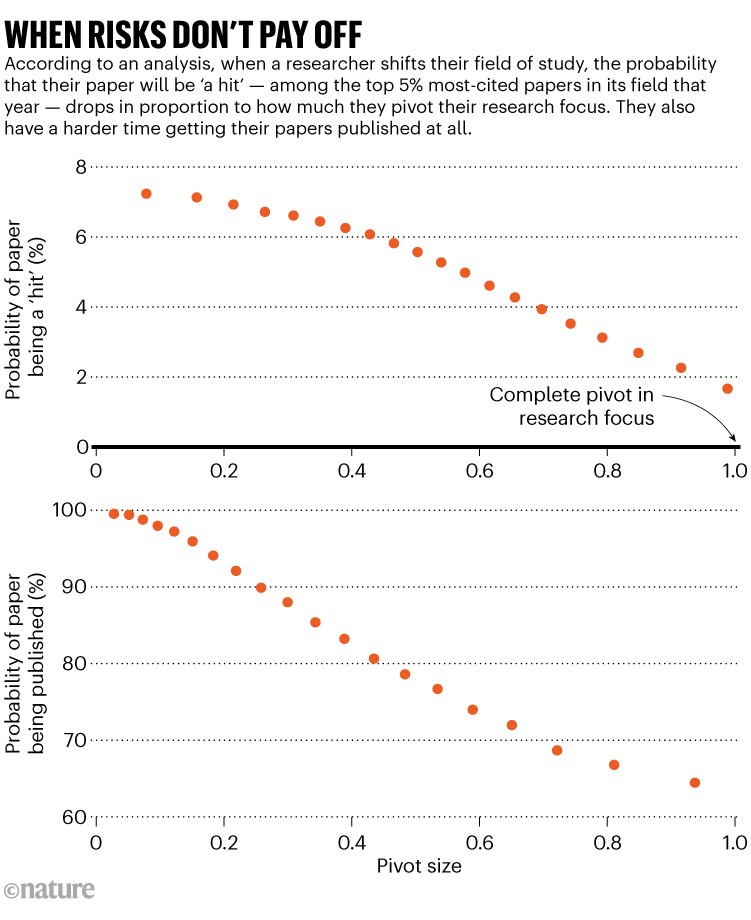

The researchers found that, the larger the pivot size, the less likely a paper is to rank among the top-5% most-cited papers published in its field that year. They also determined that it was more difficult for scientists to get their papers published after a pivot (see ‘When risks don’t pay off’).

Source: Ref. 1

“It’s a very strong relationship, and it’s pretty universal,” says co-author Benjamin Jones, an economist at Northwestern University, who points out that the trend holds for patents as well. The team analysed 1.7 million patents granted in the United States from 1980 to 2015 and found a similar phenomenon when evaluating the technology areas listed in a patent’s citations.

The authors were motivated to investigate research pivots because of the massive shift towards studying COVID-19 during the pandemic. “We thought, ‘this is great that everyone wants to help, but how helpful will it be when people are jumping in from areas further and further away [from COVID-19]?’,” Jones says. The analysis found that, even though COVID-19 research was in high demand and papers on the topic were more likely to be published in high-impact journals during the pandemic, researchers coming into the area from outside fields still experienced the pivot penalty.