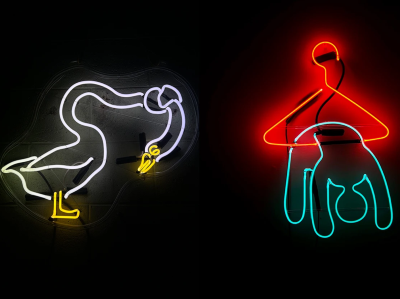

Yasmin Proctor-Kent displayed waistcoats made by her dad behind her while competing on The Great British Sewing Bee.Credit: Love Productions Ltd 2025

I love how the skills you develop as a scientist can be applied to sewing and other crafts. Like science, sewing requires creativity, as well as an initial idea or concept to get going. Both are about research and experimenting, and are iterative processes, in which you apply knowledge gained from work that you and others have done previously.

Despite these parallels, craftwork such as sewing and knitting is often undervalued or dismissed because it’s seen as ‘women’s work’. But our brains work in the same way during crafting and research. For me, training in science and having a passion for sewing have been mutually beneficial — with each discipline supporting the other and driving my success.

Growing up, sewing was always part of my background. The Great British Sewing Bee was also always a regular fixture on our family television and was a source of connection to my family after I moved out to attend university (first at the University of Sheffield, UK, where I did a master’s degree in biochemistry and genetics, then at Newcastle University, UK, where I undertook doctoral research in mitochondrial biology).

My dad was my favourite person in the world, and a keen sewer. He had an innate creativity and curiosity that shaped my own — it almost feels genetic. He trained as an armourer in the UK Royal Air Force before moving into information technology, and if something needed doing while we were growing up — electrics, plumbing, repairing a hole in an item of clothing — he just did it.

Although I get my love of sewing from him, his way of sewing was very different from mine. Before starting, he ensured that he had all the right equipment and did tonnes of research. He wouldn’t use a sewing machine to make a garment if, for example, it wasn’t historically accurate to do so, choosing instead to stitch by hand.

It was his sudden and unexpected death from cancer two years ago, aged 62, that made me decide to apply to be a contestant on the sewing bee. Sewing — and by extension the sewing bee — was our shared connection, and applying felt like a way to carry that forward.

Becoming a ‘bee’

The programme’s application process began with sending in pictures of things you’d made. This was hard for me, because I hadn’t really documented anything I’d sewn, and just had the occasional selfie I’d sent to friends or family. The next step was a series of interviews, followed by an in-person sewing audition. Initially, I wasn’t cast — and I felt a strange sense of relief, because I wasn’t sure I was really a ‘TV person’. I’m loud in volume, but not necessarily in presence. I didn’t think I fitted the mould. But two weeks later, someone dropped out, and I was invited to take their place. I couldn’t believe I’d made it through.

The filming commitment was huge. Each episode is filmed over two long days, often starting at 6.30 a.m. and not ending until 8 p.m., with two episodes filmed back-to-back and just a day off in between.

Yasmin (centre) says she got her love of sewing from her dad (left, Yasmin’s mum appears on the right). Credit: Yasmin Proctor-Kent

Siôn Phillips, a technical team leader and my manager at Leica Biosystems in Newcastle, UK, where I was then working as a lead research and development scientist in cancer diagnostics, generously gave me the time off and encouraged me to ask the company leadership if I could be filmed at work. He felt that there were not enough scientists on the programme, and that there’s a difference between saying you’re a scientist and viewers seeing you in a laboratory. It has more power.

My scientific skills and background helped to shape my approach to the programme’s challenges, and meant I was comfortable doing the research required. In the Korea-themed episode, for example, I found myself looking for papers on historical Korean clothing, translating them and applying that knowledge to make a cheollik — a traditional garment that includes a pleated skirt and is often worn by rulers and military personnel. It was no surprise to me that Kit, another contestant, also did well on the show. Kit is a mathematician, and was accustomed to engineering and transforming a 2D object to fit perfectly around a 3D form.

Career and craft

I have wanted to be a scientist for as long as I can remember. When I entered the lab at university I fell in love with research, but I knew early on in my PhD that academia wasn’t for me. I didn’t feel it was a place where I could balance work with my hobbies, which include sewing, cooking and rugby (although a torn ligament means I can no longer play).

From bench to bread: how science can enhance your hobbies

I find industry much more compatible with a strong work–life balance. Leica Biosystems’ Newcastle office, where I am normally based, even has a crafting social group. Most of the members knit or crochet, and we meet regularly in a local cafe to practice our hobbies together. It’s a reminder that science and craft often sit side by side.

Much of my earlier career experience helped me to handle the pressure of being on the sewing bee. I have a specific interest in coaching that I have been developing throughout my career. During my doctorate, I tutored for a charity called the Brilliant Club, which places PhD students in local schools for extracurricular teaching. After I concluded my PhD lab work, but before I graduated in 2021, I worked as a personal development coach with 16–18-year-olds at a local sixth-form college. At the start of the pandemic, I worked in a COVID-19 testing lab, where I joined the UK National Health Service’s professional coaching programme, and I now support an international coaching programme for women at Leica Biosystems, training future coaches.