People who have high trust in their health-care system are more likely to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19.Credit: Anshuman Poyrekar/Hindustan Times via Getty

Science has a trust problem — at least, that is the common perception. If only, the argument goes, we could get people to ‘trust’ or ‘follow’ the science, we, as a society, would be doing more about climate change, childhood vaccination rates would be increasing rather than decreasing and fewer people would have died during the COVID-19 pandemic. Characterizing the problem as ‘science denialism’, however, is misleading and wrongly suggests that the solution is to build greater trust between scientists and the public.

Indeed, the research produced by our organizations — the Edelman Trust Institute think tank and the Global Listening Project non-profit organization — suggests that trust in science and scientists remains high globally. But scientists and scientific information exist in an increasingly complex ecosystem in which people’s perception of what counts as reliable evidence or proof is influenced by myriad other people and factors, including politics, religion, culture and personal belief. In the face of this complexity, the public are turning to friends, family, journalists and others to help them filter and interpret the vast amounts of information available.

Our work suggests that the crux of science’s current challenge is not lost trust, but rather misplaced trust in untrustworthy sources. High trust levels can be dangerous when they are invested in institutions and individuals that are misinformed or not well-intentioned. In this regard, it is especially problematic when societal institutions become politicized and advocate policies and behaviours that are at odds with scientific consensus.

Misplaced trust can drive behaviours that put people’s lives at risk1,2. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, cases and deaths were higher in nations, such as the United States and Brazil, that had political leaders who dismissed the severity or even existence of the pandemic, undermined the need for masks and questioned the safety of the vaccines2–4.

In what follows, we share data on trust in science and strategies to help scientists compete with non-credentialed sources for influence.

Unpacking the real challenges

Trust in science is generally high. A survey, conducted in 68 countries between November 2022 and August 2023, found that 75% of respondents said that they trusted scientists5. In a separate study across 70 countries, conducted by the Global Listening Project between July and September 2023, 71% of respondents said that they had high trust in science (see go.nature.com/3qyawpb). And the 2024 Edelman Trust Barometer, an annual online survey of 28 countries conducted by the Edelman Trust Institute in November 2023, found that 74% of respondents trust scientists to tell the truth about new innovations and technologies6.

By contrast, our research revealed concern over the sanctity and independence of science, especially for certain topics, such as COVID-19 and climate change. More than half of Trust Barometer respondents (53%) said that science had become politicized in their country, and 59% said that governments and other large funding organizations have too much influence on how science is done6. One by-product of these perceptions has been an increase in aggression towards scientists7.

Another damaging consequence of this politicization is that it makes people more open to alternative narratives that might not be evidence-based and are often rooted in political ideologies, on topics such as climate and vaccines. This ideological schism is not defined by a pro-science versus anti-science antipathy but by a ‘my science’ versus ‘your science’ or a ‘my evidence’ versus ‘your evidence’ polarization.

People in some countries put more trust in community leaders than scientists.Credit: Jorge Mantilla/NurPhoto/Shutterstock

Often, this tension stems from the fact that scientists seek truth in experiments and data analyses, and focus on effects that manifest across large numbers of people. By contrast, the public is often focused on, and driven by, the experiences of people they know personally or vicariously. These experiences are taken as evidence and often carry more weight than peer-reviewed research.

All sides claim respect for science and evidence, hence the generally high numbers for trust in scientists across ideological groups; but each side has its own version of the ‘truth’ based on its own evidence and its own interpretation of what actions the evidence dictates6.

For example, parental concerns about the potential of vaccines to cause autism have been refuted by many scientific studies8; nevertheless, a parent’s experience with their own child or witnessing what has happened to others can be taken as direct and compelling evidence of a causal rather than a coincidental link between the timing of a measles, mumps and rubella vaccine and the onset of autism. Sometimes a sample of one, when you know that person, is more powerful emotionally, if not statistically, than a sample of 10,000.

Competing narratives around topics such as vaccines or climate change can also breed confusion, which manifests as doubt or misguided beliefs about the best actions to take, for oneself and for wider society. Doubt can weaken people’s resolve to support and follow scientific advice, especially when doing so requires effort, risk and sacrifice. Misguided beliefs, meanwhile, can lead people to act against their own or society’s best interests.

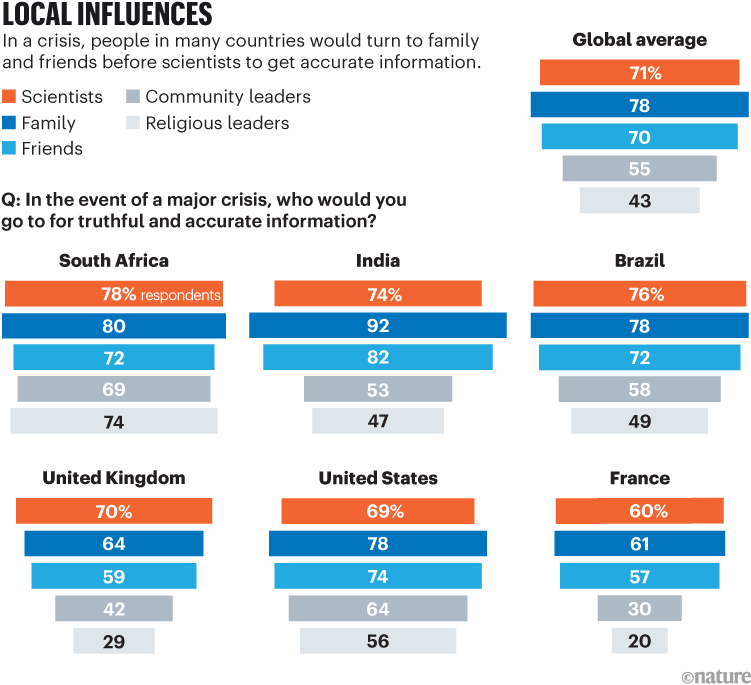

Another challenge is that many people trust non-scientists to tell them the truth about scientific matters. According to the 2024 Edelman Trust Barometer report, those with most influence include ‘someone like me’ (74%) and ‘friends and family’ (78%). Even celebrities (39%) and religious leaders (43%) enjoy substantial amounts of trust on technology and innovation matters6. Participants in the Global Listening Project study ranked family members higher than scientists when it came to who they would go to for truthful information in a crisis (see go.nature.com/3qyawpb and ‘Local influences’).

Source: Global Listening Project

Although these other sources generally lack scientific credentials, they exhibit other characteristics that people associate with legitimacy. In particular, respondents to the 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer survey conducted between October and November last year indicated that relevant personal experience (70%) is more strongly associated with source legitimacy than are formal training and academic credentials (65%; see go.nature.com/4jpparb). Although this might not affect the world of theoretical physics, it does matter in domains such as health and climate.

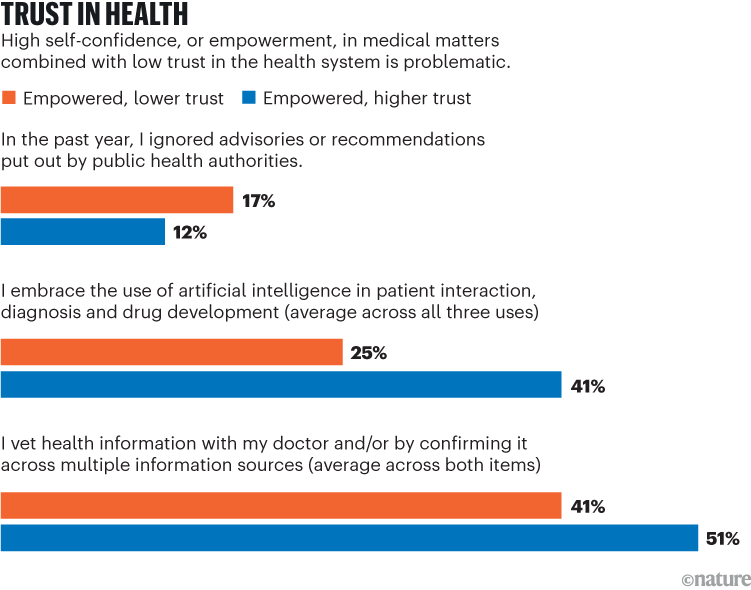

Legitimacy based on personal experience is something that people extend to themselves. The 2024 Edelman Trust Barometer Special Report: Trust and Health survey9, which involved 16 countries and was conducted in March last year, found that 65% of people are confident in their own judgement, information acumen and personal efficacy when it comes to health matters (see ‘Trust in health’). Of these ‘high health self-confidence’ individuals, 43% have relatively low trust in the health-care system9. High health self-confidence coupled with trust in health-care systems generally drives better health outcomes, but when there is a high level of self-confidence accompanied by low levels of trust, things can be problematic.

Source: Ref. 9

This is especially true when it comes to complying with public-health mandates, acceptance of medical-care innovations and being a positive influence on the health decisions of others. In the case of vaccines, those who reported themselves as being self-confident with high trust in the health-care system were more likely to be fully vaccinated (including all boosters) against COVID-19 (54%) than were those who felt equally self-confident but had lower trust (40%)9.

The threat posed by high levels of trust in non-credentialed sources is exacerbated by where and how people get their scientific information. Most often, it is through online searches, which return a mix of credentialed and non-credentialed information. Because of how people judge credibility, it cannot be assumed that they will discount non-credentialed information in favour of evidence-based, peer-reviewed findings. In fact, those with high self-confidence and little trust in official sources are often drawn to non-credentialed voices and sources8.

Because the information ecosystem contains misinformation disseminated by sources who lack scientific training but are trusted at similar levels to those who have had training, scientists need to communicate better — with more relevance, emotional resonance and empathy — if they are going to compete with other sources that are increasingly influential.

Three strategies to build trust

We recommend three strategies for scientists to enhance the influence of evidence-based, peer-reviewed information.

First, work with locally trusted sources to disseminate information. Beyond their credibility, respected individuals such as physicians and religious leaders are often in the best position to make information relevant to people’s lives and their values. Public-health authorities that issue scientific information, as well as academic and research institutions, should identify and work with such partners, and provide them with training to become trusted sources of information armed with accurate and compelling arguments to address misconceptions.

Finland is consistently recognized for having one of the best science-literacy programmes.Credit: Jonathan Nackstrand/AFP via Getty

For example, people trust family physicians more than they do scientists in some settings, and religious leaders are more influential than scientists in many countries. Employers are another potential partner: 68% of respondents said they trust their employer to do what is right when it comes to addressing their health-related needs and concerns9. This trust was higher than for government, media, business and non-governmental organizations.