You have full access to this article via your institution.

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

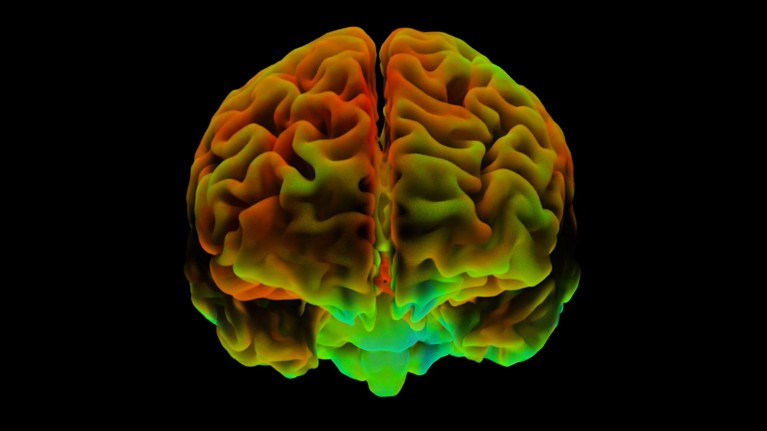

Activity in the brain’s medial prefrontal cortex shows similar patterns in optimistic people.Credit: Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute/SPL

Optimistic people share patterns of brain activity, whereas pessimists have more varying, idiosyncratic ones, a brain-imaging study reveals. Optimists also make more of a distinction between positive and negative events than pessimists do. The findings could have implications in mental-health research, researchers say, because pessimism is linked to conditions such as depression. The “dramatic part of this research was seeing a very abstract, everyday feeling — the sense that some people think alike — become literally visible in the patterns of brain activity”, says social psychologist and study co-author Kuniaki Yanagisawa.

Reference: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper

The brains of healthy people aged faster during the COVID-19 pandemic than did the brains of people analysed before the pandemic began. The accelerated ageing — recorded as structural changes seen in brain scans — occurred even in people who didn’t become infected with SARS-CoV-2, but cognitive tests revealed that mental agility declined only in those who had COVID-19. This suggests that faster brain ageing doesn’t necessarily lead to impaired thinking and memory. As yet, it’s unclear whether this pandemic-associated ageing can be reversed.

Reference: Nature Communications paper

US academics’ research-publication patterns shift fundamentally after they secure coveted tenure status. By analysing the output of more than 12,000 academics, researchers found that faculty members tend to publish the most in the year before they’re granted tenure. But once they’ve attained the job security of a tenured position, their output begins to vary across disciplines: it plateaus for biologists and others who tend to work in the laboratory, and dips for those in fields such as mathematics that generally do not require lab research.

Reference: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper

If I cover your hand and then stroke a fake one placed nearby — for purely scientific reasons, I assure you — you will ‘feel’ the touch to the fake hand as if it’s your own. This illusion demonstrates the link between vision, touch and proprioception — the ability to sense our body’s position and movement. Now we know that octopuses have the same sense of body ownership. Researchers finagled a fake arm for a plain-body octopus (Callistoctopus aspilosomatis) and saw that the animal reacted to a gentle pinch in the same way it would to a tweak of the real thing.

Reference: Current Biology paper

Features & opinion

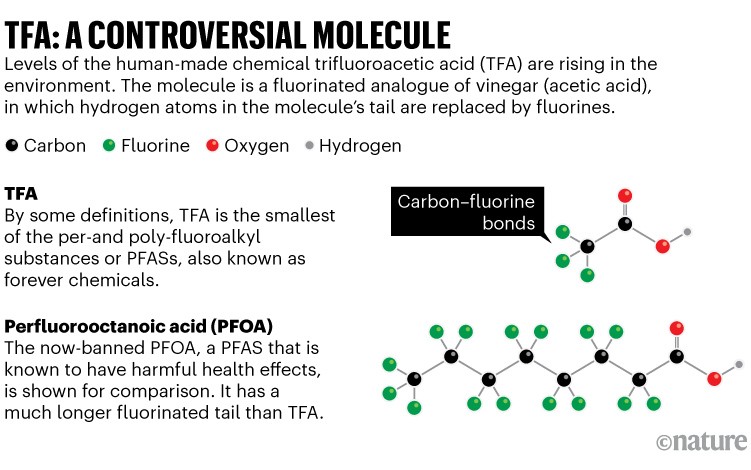

A chemical called trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) is falling in rain and its levels are rising across the planet — in lakes and rivers, food crops, trees, and in our own bodies. TFA’s strong carbon–fluorine bonds are unbreakable by natural processes, making it, by some definitions, a member of the suite of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) known as ‘forever chemicals’. Some PFASs have been deemed harmful and banned, but TFA is not widely regulated. Questions about its safety could have a far-reaching impact on industries as diverse as refrigeration and pharmaceuticals.

Scientists are perfecting their methods for making industrial volumes of custom DNA — the raw material of synthetic biology. Advances in both enzymatic and chemical synthesis are making it easier to generate highly repetitive or complex sequences. Ultimately this could help tackle a range of challenges, from cleaning up pollutants with designer bacteria to the creation of bespoke gene therapies.

Earlier this year, astronomers spent a few months measuring the odds of asteroid 2024 YR4 hitting Earth in 2032. At its peak, the risk was more than 3% — enough to trigger alerts to the United Nations and the US Space Force. We got away with it this time, but what would happen if such a space rock did turn out to be on a collision course? Plans are in place — 2024 YR4 actually arrived in the midst of a months-long simulation being run by scientists in the UN’s planetary-defense group. But the leaders of the nation best-equipped to head off such an event — the United States — are looking to cut related funding, and it’s unclear whether they’re still interested in protecting the planet, anyway.

Financial Times | 19 min read (free registration required)

Today I’m warming up for summer with the news that sweat comes out in pools on our sponge-like skin, rather than popping out in droplets. Researchers looking to understand the perspiration process squeezed six people into full-body hot-suits and heated blankets to get them glowing. Hats off to those hardy volunteers whose discomfort will help us to better understand how to keep comfortably cool.

While I break out in a cold sweat at the mere thought of participating in such a test (I hate being hot), why not send me your feedback on this newsletter? Your e-mails are always welcome at [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Jacob Smith

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma