Experimental studies were approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board, protocol 39570 “Understanding discrimination in the gig economy”, approved on 8 March 2022. This includes alterations to consent and debriefing requirements for study 2 (and the associated pilot), consistent with the Canadian federal research ethics guidelines, the Tri-council policy statement ‘Ethical conduct for research involving humans, 2nd edition (TCPS 2)’, articles 3.7 A and B, and the University of Toronto’s guidelines regarding deception and debriefing in research. Rice University and Yale University also supplied reciprocal research ethics board approval.

Study 1 context

Our first study used archival data from an online labour-market platform operating in the United States and Canada, which we refer to as SC (a pseudonym). Workers must apply for approval to work on the platform and are rigorously evaluated by SC in an interview, a verification of skills and a background check. A customer creates a job on SC by completing a survey to detail the job they want completed. Jobs fit into one of 15 unique service categories (such as appliance repair or maintenance) and usually take around a couple of hours to complete. The cost of a job is constant within the service category and is non-negotiable.

SC uses a simple algorithm to match customers to workers. The algorithm prioritizes a small set of workers on the basis of a worker’s number of jobs completed, a worker’s average rating, and whether the worker has another job in that area on the customer’s preferred day. Prioritized workers have 15 min to accept the job on a first-come, first-served basis. If the job is not accepted in 15 min, any worker who is approved to work in that service category can accept the job on a first-come, first-served basis.

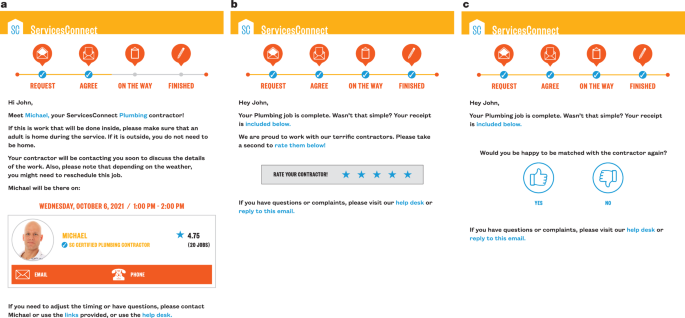

Customer characteristics and worker demographics are not recorded, nor are they direct inputs into the algorithm, so the customer–worker match is unrelated to customer and worker demographics. Moreover, customers have no control over the matching process and do not choose between workers. Once a worker accepts the job, the customer receives an e-mail message providing the worker’s name, photo, average rating to date and number of jobs completed to date (Fig. 1a). The organization does not provide workers’ demographic information to customers, but the worker’s photo is e-mailed, which can lead to the automatic perception of race47,48.

After the job has been completed, the customer receives another e-mail that gives them the opportunity to evaluate the worker. SC updated the customer rating process overnight by changing the rating scale from five stars (Fig. 1b), for which customers could choose an integer star rating to assess the worker, to a two-point scale (Fig. 1c), for which customers choose either a thumbs up or a thumbs down. The management at SC thought that this change would simplify the rating process. They did not communicate their intentions to change the rating scale, nor did they communicate any reasons for the scale change to customers.

We examined a total sample of 100,759 completed jobs, and customers chose to rate workers for 69,971 of these jobs (our main analytical sample). Analysing completed jobs makes our examination of inequality in this context arguably conservative, because results are conditional on customers not cancelling the job once assigned to a worker. We examine the rating selection processes in Supplementary Information section 1.2 (Supplementary Table 5). Of the total sample, 20,679 jobs occurred after the rating scale was changed. This setting provides an unobtrusive, well-powered examination of race dynamics in an online labour platform.

Study 1 measures

Highest rating

The main outcome of interest is the evaluation that a customer gives to a worker. On the original rating scale, customers could choose one of five different outcomes (1–5 stars in integers), responding to the message: “We are proud to work with our terrific contractors. Please take a second to rate them below! RATE YOUR CONTRACTOR!” On the new rating scale, customers could choose one of two different outcomes (thumbs up or thumbs down), responding to the question: “Would you be happy to be matched with this contractor again?” Given that we are interested in the relationship between workers’ perceived race and customer ratings across these two different scales in a regression, we needed a dependent variable that is comparable across both scales (that is, a single metric). We formed a dependent variable labelled ‘highest rating’, which takes the value of 1 if the customer submitted the maximum rating on the scale used (five stars or thumbs up) and 0 if the customer submitted any other rating (1–4 stars or thumbs down). Supplemental study A (Supplementary Information section 4) addresses the question stem difference between the five-star scale and the thumbs up/down scale as a potential alternative explanation for the results.

Income

Customers pay the same amount in the same service category, and this amount cannot be negotiated. A worker’s income is a percentage of this total amount, for which the percentage is determined by the worker’s average rating to date (their income rate). An income rate is applied after a worker has completed their first few jobs. The income represents the total dollar amount earned by a worker. This measure is normalized and we do not provide its summary statistics because we cannot disclose the raw dollar figures.

Intervention period

Rating-scale change takes the value of 1 if customers submitted their rating using the thumbs up/down scale and 0 if customers submitted their rating using the five-star scale.

Worker perceived race

SC does not collect workers’ demographic information. After a customer–worker match, SC sends customers an e-mail that contains a picture of the worker who will be completing the work (Fig. 1a). Pictures can lead to an automatic perception of race14,48. To mimic the data-generation process, we are not interested in a worker’s actual racial identity, but instead how customers are likely to perceive the worker’s race. We achieved this by having two coders independently review the profile photo of each worker on SC and record their perceptions of the individual’s race. Agreement between coders was initially 94%; in cases of disagreement, the coders discussed the photos to reach a consensus. ‘Non-white’ takes the value of 1 when a worker was perceived by our coders as non-white, and 0 when a worker was perceived as white. Hispanic/Latino workers and workers whose race was coded in a rare category (for example, Pacific Islander) or ‘other’ were included in the non-white category. We included these workers in our non-white category to be conservative in our estimates, but we also note that results are consistent no matter how this group is categorized (as white or non-white). Of the 100,759 completed jobs, 11% were completed by Asian workers, 16% were completed by Black workers, 2% were completed by Hispanic workers, 69% were completed by White workers, and 3% were completed by workers categorized as ‘non-white other’.

Control variables

Results are consistent with and without covariates and across specifications. We describe the covariates used in the main analyses below and detail several robustness models in Supplementary Information section 1. At the customer level, we controlled for a customer’s experience with SC at the time the worker accepts the focal job. ‘Experienced customer’ takes the value of 1 if the customer has requested an above-the-median number of jobs at the time the worker accepts the job, and 0 otherwise. We also include fixed effects for the metropolitan area (location) where the customer lives, based on ZIP codes. We include fixed effects for the job’s service category. At the worker level, we controlled for the number of jobs a worker has completed and their rating at the time they accept the job. Experienced worker takes the value of 1 if the worker has completed more than the median number of jobs, and 0 otherwise. Highly rated worker takes the value of 1 if the worker’s average rating at the time of accepting the job is above the median relative to other workers, and 0 otherwise. Our results are unaffected by using continuous controls (Supplementary Information section 1 and Supplementary Table 7).

Study 2

We designed an experiment to test whether using a two-point scale can causally ameliorate the racially biased evaluations observed in a five-point scale. We also wanted to test whether the effect was especially prominent among individuals holding modern racist beliefs. To replicate and extend the findings of study 1 using a causal paradigm, all information was held constant across conditions, except for worker race and rating scale.

Empirical approach and pilot testing

When we considered experimental designs, we made several empirical choices that were necessary deviations from the field context and warrant explanation here. Specifically, unlike in our field study, which was completely unobtrusive (that is, customers did not know they were being examined), studying individuals’ racist beliefs and behaviours in lab experiments can be challenging because white Americans are motivated to appear less prejudiced36,49. This is particularly an issue on online survey platforms40; participants on online platforms know they are being studied and have often completed many social-science studies, meaning they are not naive. As a result, we expected that socially desirable responses would be prevalent, making the detection of a small effect especially difficult in a lab experiment40,41, where we would also not have as much power as we did in the large-scale field observations.

Therefore, we made two main empirical deviations from the field-study context to help reduce possible demand effects and social desirability pressure in the experimental study, both of which have been substantiated by supplemental studies (Supplementary Information sections 6–9). These changes should allow more precision in our models. First, to help obfuscate the purpose of the study, we exposed participants to reviews of four workers, rather than to a single worker. Supplemental study C (Supplementary Information section 6) documents that white participants did indeed show less social desirability in responses when rating a group of racial-minority workers versus rating an individual racial-minority worker.

Relatedly, our instructions in our main experiment asked participants to rate the platform (HomeServices Pro) rather than rate the workers. Although it is possible that when rating the organization respondents are thinking about organizational reputation versus their own beliefs, this measure should show high convergence with individuals’ beliefs about the status of individuals from racial groups affiliated with the organization. This argument is supported by literature showing that people project their own biases onto others, and this increased distance between the rater and rated target can help to better identify individuals’ honest stereotypical beliefs by reducing social desirability43. Supplemental study D (Supplementary Information section 7) shows evidence that white participants show less social desirability in responses when instructed to rate the organization versus its workers.

Supplemental study E (Supplementary Information section 8) addresses two more empirical issues. First, we examined whether a single-item measure for modern racist beliefs showed convergent validity with longer-established measures of contemporary racist beliefs (Supplementary Table 11). This is because we include this single item in the main experiment to help reduce participants’ awareness of the purpose of the study. Second, in this supplemental study we also document evidence for our assumption that when participants are using a five-star scale, they feel more encouraged to include their personal beliefs and opinions in their evaluations, but when they are using a thumbs up/down scale, they feel less encouraged to do so.

Pre-registration

We pre-registered the design and analysis plan for this study (https://aspredicted.org/31P_L85). Data and materials are located in our OSF folder (https://osf.io/mkbfp/). All studies received university institutional review board approval (ERB protocol 39570). We also note that we ran a pilot test of the full study 2 that showed results consistent with those reported here (Supplementary Information section 9 and Supplementary Table 12).

Participants

On the basis of a pilot study, we predetermined to collect 650 complete responses in which participants passed a bot-check question, with the intention of recruiting approximately 150 participants for each cell of the design. We recruited US-based adult participants using the Centiment panel service, which balances participant recruitment based on demographics and location. We collected a total of 807 responses, 652 of which were complete. We focused our analyses on these 652 responses (from 311 men, 330 women, 5 non-binary/third gender and 6 who preferred not to say; mean age = 49.86, s.d. = 16.98). Results with incomplete data and failed bot checks are consistent with those reported here. We chose not to measure participants’ race in this study because doing so might shape how participants respond to the racist-beliefs measure, also positioned in the demographic section. However, we note that the panel was balanced on demographics and location to be representative of the US population.

Procedure, manipulation and measures

Study 2 used a two (race: white versus non-white) by two (rating scale: five-star versus thumbs up/down) between-subjects experimental design. In our research design, participants were unaware they were in an academic research study, which is particularly important for studies of racist beliefs40. Specifically, we told participants that we were a new start-up company called HomeServices Pro that uses an app to connect people with home-service providers and that the survey was designed to help us learn about how customers respond to different information. After reading this introduction, participants were asked to read four positive customer testimonials in randomized order (for example, “Overall, I’m pleased with the tile work that Matt did in my bathroom.”). Each customer testimonial had a photo of the worker being referenced (from the Chicago Face Database50). To manipulate worker race, participants were randomly assigned to read identical customer testimonials that either referred to four separate white workers (the white workers condition) or two white workers and two racial-minority workers (one Black and one non-white Hispanic/Latino man; the non-white workers condition; see Fig. 3 for example stimuli). The manipulation therefore varied only whether participants viewed two more white workers or racial-minority workers.

Next, participants were asked: “Based on these reviews, what rating would you give HomeServices Pro?”. They were then randomly assigned to use a thumbs up/down or a five-star scale to respond (Extended Data Fig. 1). We standardized these ratings with respect to each scale and combined them to be able to compare participants’ ratings on the same metric, as specified in the pre-registration. Even so, results are consistent when running the same analysis as study 1 using a dichotomous outcome variable (Supplementary Table 10).

Participants subsequently reported their gender and age and then were asked three questions about their political opinions in randomized order, in which our measure of modern racist beliefs was embedded. We measured participants’ modern racist beliefs with the single item: “How much employment discrimination do Blacks and other racial minorities face in the U.S.?” (1 = none to 7 = a great deal), adapting items from the symbolic racist-beliefs scale (“How much discrimination against blacks do you feel there is in the United States today, limiting their chances to get ahead?”44) and modern racist-beliefs scale (“Discrimination against Blacks is no longer a problem in the United States”34). Separate t-tests showed that this measure was not affected by scale condition (t(650) = −1.28, P = 0.200, Cohen’s d = −0.10) or worker race condition (t(650) = −0.14, P = 0.892, Cohen’s d = −0.01). This measure was reverse-coded such that higher values represented greater modern racist beliefs (reluctance to acknowledge the existence of racial discrimination; mean = 3.69, s.d. = 1.79). The last two questions about political opinions were filler questions about economic conservatism based on questions that appeared in the Pew Research Center survey on political polarization from 2001 (see all the measures on OSF). Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are shown in Supplementary Table 8.

Study 3

Pre-registration

We pre-registered the design and analysis plan for this study (https://aspredicted.org/5Y4_7D4). Data and materials are available from our OSF folder (https://osf.io/mkbfp/).

Participants

We predetermined to collect 1,500 complete responses from US-based adult participants through Prolific on the basis of a pilot study. We collected a total of 1,589 responses, 1,503 of which were complete. Following our pre-registration plan, we excluded from our analyses the responses from 50 participants who were suspected of taking the survey more than once (based on time stamps and duplicated IP addresses; we did not observe any duplicated Prolific identities). We also excluded from our analyses the responses from 18 participants who did not provide the correct answer to our reading-comprehension check question. This left us with a final sample size of 1,435 (693 men, 706 women, 28 non-binary/third gender and 8 who preferred not to say; mean age = 39.85, s.d. = 13.31; 923 white, 202 Black, 96 Latino, 145 Asian, 7 Native American, 2 Pacific Islander, 60 multi-race or ‘other’). Results with incomplete data and failed reading-comprehension checks are consistent with those reported here.

Procedure, manipulation and measures

Study 3 used a four-condition (rating scale: five-star versus thumbs up/down versus six-point versus ten-point) between-subjects experimental design. Participants were randomly assigned to view one of the four rating scales and were presented with our three dependent measures: expression of personal opinions, focus on good versus bad, and captures biased opinions. We first measured participants’ perceptions of expression of personal opinions, which read: “Please look at the commonly used question in the image above. When using this question to rate an object or target, to what extent do you agree that it would… (a) allow you to sufficiently express your opinions, (b) allow you to freely express your feelings about the object or target, (c) encourage you to use your own opinions in your evaluation and (d) make you feel like it’s legitimate to include your own opinions and beliefs in your evaluation” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.91). On the same page, participants were asked about their focus on good versus bad performance with the question: “Continuing to think about the image we showed you above, to what extent does it encourage you to focus only on whether the object or target is good versus bad (NOT including your personal opinions)?”. Finally, on the subsequent page, participants were again shown their randomly assigned rating scale and were asked: “When customers use this question to rate an object or target, to what extent do you agree that it would… (a) capture customers’ biased opinions?, (b) allow customers to freely express their biased feelings about the object or target, (c) encourage customers to use their biased opinions in their evaluation, and (d) make customers feel like it’s legitimate to include their biased opinions and beliefs in their evaluation?” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.90). These four items constituted our measure of ‘captures biased opinions’, assessing the extent to which participants thought each of the four rating scales allowed for biased opinions (such as racist beliefs) to be included in one’s ratings. We intentionally made customers the referent of this measure, rather than the focal participant, to reduce potential social desirability in responses when asking about one’s own biased behaviour43.

As an exploratory measure, we assessed participants’ level of exposure to the rating scales they were asked about when evaluating products and services (1 = I never use this scale, 7 = I always use this scale; Supplementary Information section 3).

Participants subsequently responded to our reading-comprehension check question and reported their gender, age, race, political conservatism, level of education, English proficiency, voluntary comments about the study and Prolific identity before exiting the survey website. Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are shown in Supplementary Table 8.

Study 4

Pre-registration

We pre-registered the design and analysis plan for this study (https://aspredicted.org/4LB_F65). Data and materials are available from our OSF folder (https://osf.io/mkbfp/).

Participants

We conducted prescreen surveys of white US-based participants on Connect, which contained a single-item measure of modern racist beliefs from study 2 along with five filler questions. We identified white participants who had relatively strong modern racist beliefs by selecting those who responded with a 5, 6 or 7 on the modern racist beliefs scale, and invited them to participate in study 4. For study 4, we predetermined to collect 570 responses on the basis of a pilot study. We ended up with a total of 580 responses, 571 of which were complete. Following our pre-registration plan, we excluded from analyses the responses of five participants who were suspected of taking the survey more than once (based on time stamps and duplicated IP addresses), 29 responses from participants who indicated they were not white, 6 response from participants who incorrectly answered an open-ended bot-screening question, and three responses from participants who incorrectly answered our third bot question (all passed the second bot question). This left us with a final sample of 528 white participants (283 men, 244 women, 1 preferred not to say; mean age = 43.12, s.d. = 12.75). Results with incomplete data and failed bot checks are consistent with those reported here.

Procedure, manipulation and measures

Study 4 used a two-condition (rating scale: five-star versus five-star with intervention) between-subjects experimental design. The design of the study was similar to that of study 2, except: first, all participants were asked to rate a company with two non-white workers and two white workers (the non-white workers condition in study 2; see Fig. 3 for example stimuli); second, study 4 did not include a measure of racist beliefs (because we measured this separately before recruiting participants); and third, study 4 included a ‘five-star with intervention’ condition and omitted the thumbs up/down scale condition. Thus, all participants viewed customer testimonials of four workers of a company (including racial-minority workers) and were asked to rate the company using the scale they were randomly assigned to. Participants then completed a demographics questionnaire, completed three bot-check questions, and exited the survey website. Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are shown in Supplementary Table 8.

Our manipulation of the five-star scale was identical to that in study 2. In the intervention condition, participants saw the same five-star scale with the extra text: “when answering this question, please focus ONLY on whether the work itself was good (5 stars) versus not (other values)”. In a separate pre-registered study (https://aspredicted.org/JMQ_X39; Supplementary Information section 11) with a separate sample of 287 participants, participants in the intervention condition rated the scale as making them feel significantly less open to including their opinions and beliefs (mean = 4.19, s.d. = 1.79) than participants in the five-star scale condition (mean = 5.40, s.d. = 1.48), t(285) = −6.23, P < 0.001, 95% CI, [−1.59, −0.82], Cohen’s d = −0.74. Furthermore, participants in the intervention condition (mean = 5.70, s.d. = 1.41) reported that the scale would encourage them to focus on good or bad performance significantly more than those in the five-star scale condition (mean = 5.16, s.d. = 1.58), t(285) = 3.07, P = 0.002, 95% CI, [0.20, 0.89], Cohen’s d = 0.36. Overall, this separate pre-registered experiment ensured that we designed a successful intervention in study 4.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.