Space telescope orbit and attitude simulation

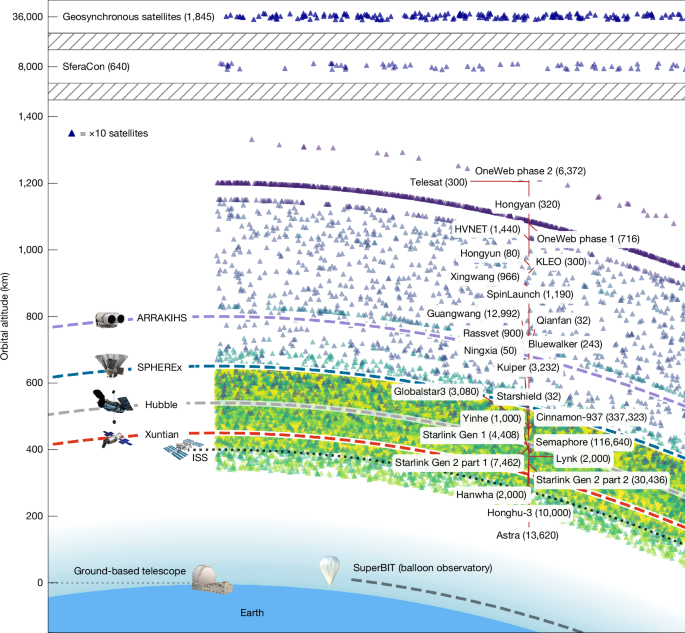

The key objective of this study is the prediction of the number of satellite trails in future and present space telescopes in different configurations, represented by the Hubble Space Telescope (540 km), the terminator-aligned sun-synchronous orbit SPHEREx space telescope (700 km), Xuntian Space Telescope (450 km) and the proposed ESA mission ARRAKIHS (approximately 800 km). The main properties of the four telescopes are summarized in Extended Data Table 2. Xuntian and ARRAKIHS are missions still in development, and their configurations might change before launch. In particular, ARRAKIHS proposed orbit ranges from 650 km to 800 km (ref. 22). Because satellite contamination becomes less frequent at higher orbits, we chose a best-case scenario with an 800-km orbit.

The satellite trail simulation process is schematized in Extended Data Fig. 1. For each observatory, we assumed a survey plan that consisted of a series of pointings (right ascension and declination) taking place at an associated epoch (epoch at exposure start (tstart) and exposure end (tend) with a certain exposure time (texp = tend − tstart)). The available regions on the sky depend on the telescope orbit (as defined by the two-line element) and epoch (that is, a telescope cannot observe a region blocked by Earth), as well as specific survey constraints (Sun avoidance, Earth limb and maximum zenith angles) for each telescope, as summarized below. For Hubble simulations, we randomly selected archival exposures (right ascension, declination, tstart and texp) obtained with the wide-field channel of the Advanced Camera for Surveys during 2023–2024, assuming the closest orbit on time from its recorded history. The typical exposure time was \({t}_{\exp }={540}_{-200}^{+530}\,{\rm{s}}\).

To simulate the survey plan, orbital position and attitude of the SPHEREx, Xuntian and ARRAKIHS space telescopes, we chose random locations in the sky that were accessible with the adopted constraints of each telescope. For SPHEREx, we assumed a maximum zenital angle of 35°, a solar avoidance angle of 91° throughout the exposure and an exposure time of 112.5 s on h = 650 km terminator-aligned Sun-synchronous orbit37. Similarly, we chose h = 800 km terminator-aligned Sun-synchronous orbit for ARRAKIHS, with a fixed exposure time of 600 s (ref. 22) and 7.6° Earth-limb angle (as in Hubble). Finally, Xuntian was assigned the same orbit as the Tiangong Space Station (LEO; h = 450 km; inclination i = 41.47°), a 55° solar avoidance angle, 7.6° Earth-limb angle during the whole exposure and a random exposure time following the same distribution as the Hubble observational record, on the basis of their similar available time-per-orbit, altitude, aperture and spatial resolution.

Satellite constellation orbit

The orbital parameters for the satellite constellations were generated using the Planet4589 public database38, which provides data on the orbital altitude, number of shells, number of orbital planes and satellites per plane for each FCC/ITU-registered satellite constellation. In addition to the simulated satellite constellations on the basis of the orbits described in Extended Data Tables 1 and 3, we included a baseline of 8,544 existing large satellites, including all artificial satellites already orbiting Earth, excluding (1) those classified as part of constellations to avoid duplication; (2) CubeSats; (3) debris; or (4) objects known to be too small to be observed, such as Westford Needles. To analyse the effect of an increasing population of artificial satellite constellations, we randomly selected a varying number of satellites, starting from a baseline population of approximately 100 up to one million satellites. The simulated satellites were randomly selected from the pool described for each simulation, ensuring that we sampled the potential variability across scenarios.

On the basis of the orbital parameters and telescope survey plans, the Cartesian geocentric position \(({\overline{x}}_{t}=(x,{y},{z},{t}))\) of the telescope (observer) during the exposure was calculated (Extended Data Fig. 7). In parallel, the coordinates of the satellite constellation were estimated \(({\overline{x}}_{{\rm{s}}})\). The apparent locations on the sky (right ascension and declination) of Earth, Sun, Moon and the artificial satellite constellation were computed within the local reference frame of the telescope. The locations and extensions of Earth and the Moon were determined using their predicted ephemeris and physical properties, whereas the apparent locations of the artificial satellites were simulated as a function of time by propagating their orbits. Thanks to the described approach, we can determine which satellites are visible (not behind Earth); illuminated by the Sun, Moon or Earth; and/or inside the FOV of each telescope. The code is on the basis of Python/Skyfield39. The final product is a database (satellite trails) of the location of each satellite that crosses the FOV, including its brightness, apparent angular velocity, illumination and phase angles (for the Sun, Moon or Earthshine), distance to the observer and location in the sky as a function of time.

Satellite trail brightness

The surface brightness of satellite trails depends on several factors, including the (1) brightness of the light source; (2) bidirectional reflectance distribution function40 of the satellite and its distance to the observer; and (3) orientation of the reflecting surfaces to the light source41. For order-of-magnitude estimations, we implemented some simplifying assumptions.

A satellite located at a distance dsat (in metres) from a space telescope with a mirror diameter Dmir crossing the FOV leaves a trail with a width θsat (in steradians)27,42:

$${\theta }_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}=\left(\frac{{D}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}+\,{D}_{{\rm{mir}}}^{2}}{{d}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}}\right)+{\sigma }^{2},$$

(1)

where σ represents the optical resolution of the telescope, and Dsat is the equivalent diameter (defined as the diameter of a circle with the same area) of the cross-sectional area of a satellite, assuming a random orientation with respect to the observer. The area of the extended solar panels in new-generation satellites can range from 1 m2 to 125 m2 (ref. 17). In this study, we assumed a uniform distribution between these two extreme values.

The reflected spectral flux density (FR,sat→obs; in W m−2 Hz−1) of a LEO satellite with cross-sectional area Asat simulated as a Lambertian diffuse sphere can be approximated as a combination of the reflected light from the Sun (F⊙→sat), the Earthshine (F⊕→sat) and the Moonshine (F☾→sat)43 as

(2)

where p is the albedo of the satellite, and γ depends on the satellite illumination phase angle (ϕ) from each source (Sun, Moon and Earth) as

$$\gamma =\frac{2}{3{\rm{\pi }}}(\sin \,\phi +({\rm{\pi }}-\phi )\cos \,\phi ).$$

(3)

In addition, satellites emit thermal black-body radiation (FT,sat→obs):

$${F}_{{\rm{T}},{\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}={\epsilon }\frac{{A}_{{\rm{sat}}}}{{d}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}}B(\lambda ,{T}_{{\rm{sat}}}),$$

(4)

where ϵ = 0.9 is the thermal emissivity44 that reflects a fraction of thermal radiation from Earth (FT,⊕→sat→obs) as well43,45:

$${F}_{{\rm{T}},\oplus \to {\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}={\gamma }_{\oplus }\frac{{\epsilon }p{A}_{{\rm{sat}}}}{{d}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}}{\left(\frac{{R}_{\oplus }}{{R}_{\oplus }+{h}_{{\rm{sat}}}}\right)}^{2}B(\lambda ,{T}_{\oplus }).$$

(5)

The total optical and infrared emission from a satellite (Fsat; in W m−2 Hz−1) received by an observer would then be:

$${F}_{{\rm{sat}}}=\,{F}_{{\rm{R}},{\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}+{F}_{{\rm{T}},{\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}+\,{F}_{{\rm{T}},\oplus \to {\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}.$$

(6)

Because the satellites move across the FOV, their flux is deposited on the detector along the trail. The surface brightness (Σsat; in W m−2 Hz−1 arcsec−2) can be modelled as46:

$${\varSigma }_{{\rm{sat}}}=\frac{{F}_{{\rm{sat}}}}{{A}_{{\rm{trail}}}}\times \frac{{t}_{{\rm{eff}}}}{{t}_{\exp }}$$

(7)

where \({A}_{{\rm{t}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{l}}}={{\rm{\pi }}\theta }_{{\rm{s}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}}^{2}/4\) is the observed angular area of the satellite image, texp is the exposure time (in seconds) and \({t}_{{\rm{eff}}}=\frac{{\theta }_{{\rm{sat}}}}{{\omega }_{{\rm{sat}}}}\) is the effective time that a satellite that moves in the focal plane with an apparent angular velocity ωsat (arcsec s−1) takes to cross its own trail width (θsat). Finally, the surface brightness magnitude of the satellite trail µsat (in mag arcsec−2) will be:

$${\mu }_{\mathrm{sat}}=-2.5{\log }_{10}({\varSigma }_{\mathrm{sat}})-\mathrm{56.1.}$$

(8)

Following a previous study45, we assumed T⊕ = 290 K for the temperature of Earth and a surface temperature Tsat = 280 ± 3 K for satellites. Ground-based measurements estimated that the optical and near-infrared albedoes can vary between 0.1 and 0.5 for LEO satellites47,48, even higher (p ≈ 1) for small pieces of debris. For the purpose of this study, we assumed a uniform distribution for p in the range [0.1–0.5].

The V-band surface brightness magnitude of Sun-illuminated Earth is µV ≈ 2 mag arcsec−2, whereas the magnitude of the full Moon is mV = −12.74. To estimate the Earthshine (F⊕→sat) and Moonshine (F☾→sat), we first scaled the solar spectral energy distribution49 in the V-band to the observer magnitude from Jet Propulsion Laboratory Horizons in the same band. We then integrated their spectral surface brightness by the visible illuminated area (in square degrees) for each satellite’s point of view. For the Moon, the illuminated area is defined by its phase at the epoch of the simulated exposure, whereas for Earthshine, only the areas inside the visible horizon can illuminate the satellite. Extended Data Fig. 6 represents two examples of the resulting contribution of each component to the total observed spectral energy distribution of the satellites.

Extended data

Properties of satellite trails

For space telescopes, exposures with lower-limb angles will present a higher probability to encounter a satellite because they integrate along a thicker layer of LEO. Depending on the altitude of the telescope and the limb avoidance angle, a LEO telescope can observe satellites at lower altitudes than itself30. Extended Data Fig. 2 represents the minimum observable orbit accessible from a LEO telescope as a function of the limb avoidance angle and altitude of the telescope. On the basis of these limits, Hubble can, in principle, detect satellite constellations at h ≈ 350 km or above, which comprises practically the total population of satellites in orbit, planned or already launched (Extended Data Table 1).

Extended Data Fig. 3 represents the distribution of the number of satellite trails detected as a function of the observation distance to Earth’s limb angle. As expected, the number of satellite trails per exposure increased with lower Earth’s limb separation angles. SPHEREx strict zenithal angle configuration prevented most satellite trails from entering its large FOV (Extended Data Table 2). For ARRAKIHS and Xuntian, Earth’s limb separation angles lower than 30–40° result in hundreds to thousands of satellite trails in the simulations with the highest number of satellites (Nsat = 5 × 105−106).

Another important factor is the exposure time. Longer exposure times can lead to an increased number of satellite trails. Extended Data Fig. 4 represents the number of satellite trails detected on each exposure as a function of the exposure time. The results show that, although shorter exposure times present less satellite trails, the dependence with the limb angle is more clear and pronounced. Extended Data Fig. 4 is limited to Hubble and Xuntian because the observing plans for SPHEREx and ARRAKIHS involve fixed exposure times (Extended Data Table 2), designed in combination with their polar Sun-synchronous orbits.

Finally, we explored the dependence of the brightness of the satellite trails as a function of the distance to the satellite and the trail width (Extended Data Fig. 5). We found that the maximum surface brightness tends to occur at distances from the observer similar to 103 km, except SPHEREx, which presented its maximum at 102 km. Satellites at long distances (dsat = 105 km) from Hubble presented high surface brightness as well (µV ≈ 15 mag arcsec−2). Several factors dominate this distribution. The equations in ‘Satellite trail brightness’ (Methods) describe that at large distances from the telescope, satellites are unresolved, and their trail width (θsat) is thus limited by the angular resolution of the telescope. At the same time, satellites at longer distances move relatively slower across FOV, increasing teff. Alternatively, at lower values of dsat, the received flux Fsat increases as \({d}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}\), similarly to the angular area of the trail (Atrail) cancelling each other. However, at close distances, the satellites take less time to cross the FOV, effectively decreasing the detected surface brightness in the simulated trails50,51.