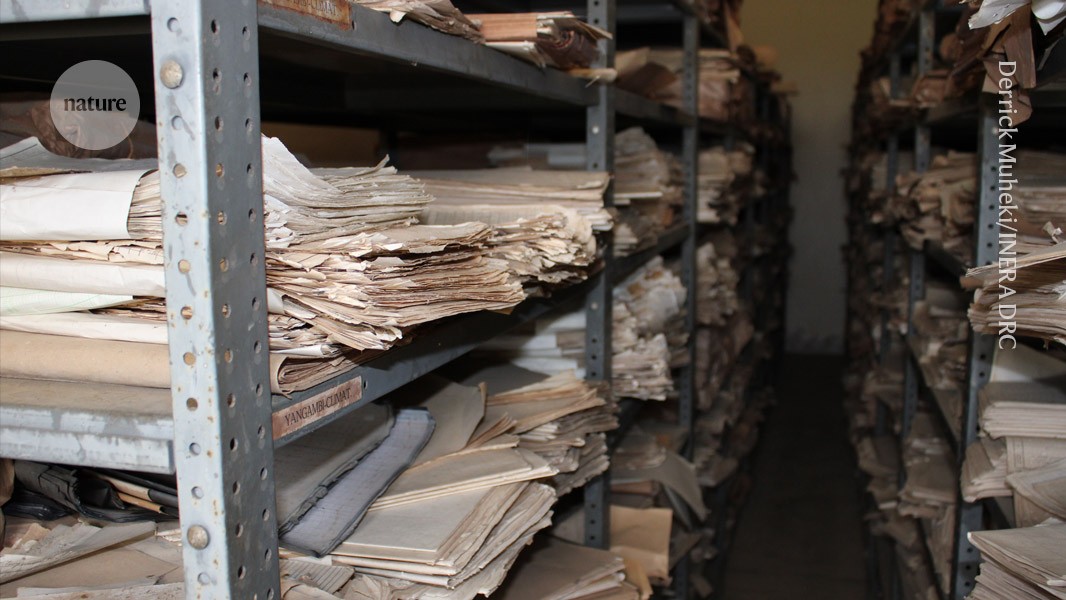

Thousands of paper documents in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s meteorological archives are now being digitized.Credit: Derrick Muheki/INERA DRC

How can countries find out how climate change will affect them at a regional scale? Can artificial intelligence (AI) help to forecast hurricanes and other extreme weather events? And has the world already blown past the most ambitious target of the Paris climate agreement — to limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels?

The need to address these and other questions is spurring researchers to tap into vast, unused repositories of handwritten weather records that span more than two centuries. These troves of valuable — but in some cases unreadable — data are now becoming easier to access with new, more sophisticated machine-learning tools.

“All meteorological services around the world have some basement where they store data from the 1800s that has not been digitized,” says Marlies van der Schee, a climate scientist at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute in De Bilt. “For many institutes, they don’t even know what is in their archives.”

Searching for data

In the quest to gather missing climate data, climate scientist Derrick Muheki has travelled farther than most. To access the meteorological archives of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) — which contain records from when the DRC became independent in 1960 collected from 37 weather stations across the country — Muheki had to fly from Kinshasa to Kisangani in the country’s north, travel along the Congo River by boat and then take an unpaved road on a motorcycle to reach the Yangambi branch of the DRC’s National Institute for Agronomic Research (INERA). There, he spent two months earlier this year scanning thousands of pages of weather logs.

Muheki had to bring enough batteries to power his digital camera for the duration of the trip, as the remote branch of INERA is not hooked up to the DRC’s national grid. He learnt some of the Bantu language Lingala so that he could communicate with other INERA staff members. He says it helped that many of the words were similar to the language he grew up speaking in his native Uganda.

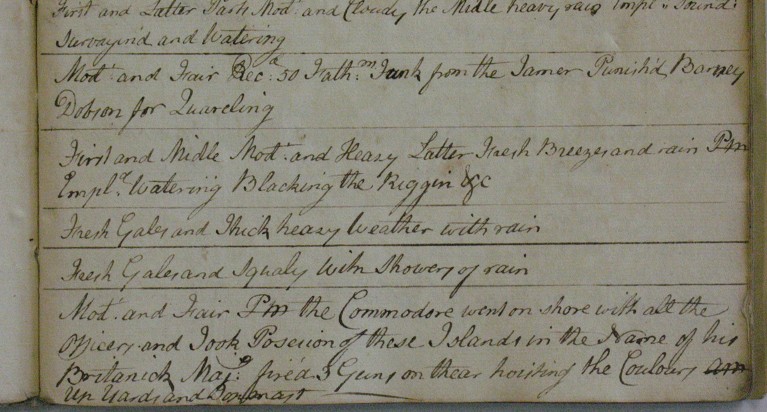

Weather reports from old ships’ logs — such as this eighteenth century document from British vessel HMS Dolphin — contain data that can be fed into climate models. Credit: The History Collection via Alamy

After returning to his research group at the Vrije Universiteit in Brussels, Muheki began to extract data from the more than 9,000 scanned images using a machine-learning tool he designed for reading the weather logs, called MeteoSaver1.

In initial tests, MeteoSaver could only transcribe the data with 75% accuracy, but further refinements and training of its neural network — on the basis of an open-source package for handwritten-text recognition called Tesseract — have pushed that to 90%, he says.

The resulting data will provide crucial information about how conditions have changed over time in the world’s second largest rainforest. Climate scientist Wim Thiery, Muheki’s adviser at the Vrije Universiteit, says that because of a lack of information about past temperatures, the forested heart of the African continent had a major data gap in the 2021 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which assessed the severity and speed of global warming in various parts of the world. He hopes that efforts such as Muheki’s will help to rectify this.

Forgotten figures

Muheki’s logistical hurdles were unusual, but the DRC is not the only country that is yet to fully digitize its weather records.

“There are paper records still languishing in archives all over the world,” says Ed Hawkins, a climate scientist at the University of Reading, UK. These include millions of unused rainfall observations in the UK’s National Meteorological Archive.

Is it too late to keep global warming below 1.5 °C? The challenge in 7 charts

Hawkins has managed several projects that relied on citizen scientists to manually transcribe climate records. Ten years ago or so, machine-learning tools just weren’t up to the task, he says. The hardest part for AI tools is not reading handwritten text, but recognizing the tabular structure in the documents. “When I and colleagues started trying [AI] tools out, they just would not work on tabulated numbers,” says Hawkins. “It wasn’t in their training.” Much of Muheki’s work consisted of developing custom algorithms for doing just that. Now, the tools are finally becoming good enough to match human performance, says Hawkins, who is a co-author on the research paper that describes MeteoSaver.

Similar efforts by other teams are showing that machine learning could drastically speed up the rate of recovery of historic records. “It’s really a revolution in our ability to rescue data,” says Thiery.