Tissue sample collection, preservation and processing

Back skin samples from age-matched adults and one litter of neonatal naked mole rats (Heterocephalus glaber) were maintained at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio for unrelated studies performed under protocols approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; 20210034AR). Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were maintained at the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC) at Oregon Health and Science University for unrelated studies performed under protocols approved by Oregon Health and Science University IACUC (IP03716, IP03276, IP00367). The ONPRC is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (Animal Welfare Assurance D16-00195) and registered with the USDA (92-R-001). Rhesus macaque back skin samples were shared through the ONPRC tissue distribution programme. Common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) were maintained at the Southwest National Primate Research Center at Texas Biomedical Research Institute for unrelated studies performed under an approved animal use protocol (assurance number D16-00048). Back skin was recovered from the above species at necropsy after euthanization for unrelated studies. Skin samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight and stored in 70% EtOH until tissue processing for paraffin embedding or fixed in 4% PFA, shipped to Washington State University in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on ice, and embedded in OCT (Fisher) before cryopreservation at −80 °C. Biological replicates were compiled from samples collected across different litters unless otherwise specified. Histological analyses of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), long-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus capensis) and short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) trunk skin were performed using trunk skin samples obtained by the Plikus laboratory at the University of California, Irvine, from the NOAA (Southwest Fisheries Science Center, La Jolla, California) under the destructive loan permit. The analysed specimens included: D. capensis (numbers KXD0225, KXD0226, 1741-2023 Dc2301B), D. delphis (numbers BLH0012, KXD0357, 585-2022 Dd2202B) and T. truncatus (numbers KXD0410, KZP0069, 812-2022 Tt2202B). North American grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis), a mix of males and females ranging in age from to 8 to 21 years in the summer of 2023, were housed at the Washington State University Bear Research, Education, and Conservation Center. North American grizzly bears were anaesthetized, and biopsies were collected from the dorsal skin of the rump (lower back) for unrelated studies related to subcutaneous fat performed under Washington State University IACUC-approved protocols (6546). Skin samples used in this study were the whole 6-mm diameters of discarded skin from the biopsies, which were used to sample subcutaneous fat. Representative histology in Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2b is from a 21-year-old male (haematoxylin and eosin; H&E) and female (Herovici), which were both born in the wild. Mice (Mus musculus) used in this study were of a mixed WT C57BL/6 background housed at Washington State University in a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum in a climate-controlled facility set to approximately 68–73 °F and 40% humidity. K14-Cre;Lef1fl/fl (Lef1-eKO) mice were generated by crossing Tg(KRT14-cre)1Amc/J (Jackson Laboratory, 004782)61 with B6.Cg-Lef1tm1Hhx/J (Jackson Laboratory, 030908)62. Housing and sample collection was conducted in accordance with Washington State University IACUC-approved protocols (6723, 6724). Paraffin-embedded 3mo K14-Noggin and C57BL/6 mouse digits analysed in this study were archived from a previous study4 and shared with the Driskell laboratory upon request. K14-CreERT;Bmpr1afl/fl and K14-CreERT mice53,63,64 used in this study were housed at the University of Warsaw. The animal studies were approved by the First Local Ethics Committee: no. 971/2020 as of 28 January 2020, no. 1669/2025 as of 18 March 2025. The studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. K14-CreERT;Bmpr1afl/fl and K14-CreERT mice were all treated with tamoxifen (12.5 mg ml−1 in 10% EtOH) topically to the paws from P1 to P5 and then aged to P56. K14-CreERT;Bmpr1afl/fl were labelled TAMX (tamoxifen-induced knockout group), and K14-CreERT mice were labelled Ctrl (control, tamoxifen-induced without gene knockout) in Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 5i. Collected digits were fixed for 24 h in 4% PFA at 4 °C, then in 0.5 M EDTA (pH 7) for 6 days at room temperature (to soften the bone and nail), before being moved to 30% sucrose at 4 °C and frozen in OCT. Gestational human tissue samples ranging from GW7 to GW20 were obtained by the Birth Defects Research Laboratory at University of Washington under University of Washington institutional review board (IRB)-approved protocols with maternal written consent (University of Washington STUDY00000380; received under Washington State University 19680). Fetal tissues were obtained surgically, and although there is a possibility of samples being damaged by this process, we did not observe damage in the samples analysed in this study. Adult human tissue samples were obtained by Advanced Dermatology in Spokane, Washington, as surgical discard tissue after informed consent and in accordance with IRB-approved protocols (Washington State University 19796). All human tissue samples were deidentified before receipt at Washington State University and analysed in accordance with Washington State University IRB-approved protocols, as specified above. As they were surgical discards, samples came from a variety of anatomical sites, including the trunk skin of the torso and the skin of the face or head. Human tissue samples were processed for paraffin embedding as described above except for the adult samples, which were fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Fisher) instead of PFA. Pigs (Sus scrofa) were housed at Washington State University under approved Washington State University IACUC and USDA protocols in a climate-controlled facility ranging from 70 °F to 80 °F and 30% to 50% humidity. Housing included a 12-h light/dark cycle with regular feeding and ad libitum water. Some fetal pigs were obtained from Biology Products; their age was estimated on the basis of length, and they were exempt from Washington State University IACUC approval. Embryonic day 90 fetal pigs were collected postmortem from a pregnant pig with known date of conception under WSU IACUC-approved protocols (6492). Skin samples from all fetal pigs were collected from the upper back along the dorsal midline. Postnatal pig samples were collected postmortem from pigs either housed at Washington State University, obtained from local farmers, or postmortem from local butchers in accordance with Washington State University IACUC-approved protocols (6492). Skin samples from all postnatal pigs were collected from the upper back along the dorsal midline from multiple litters owing to limited litter sizes and difficulty in obtaining animals. Fetal pigs obtained from Biology Products were generally unpigmented and of unknown background and multiple litters. One litter of known embryonic day 90 pigs (used for histology, immunostaining and scRNA-seq) was collected from an unpigmented pregnant sow raised on a local farm of mixed Yorkshire and Red Duroc background. Postnatal pigs obtained from local farmers or butchers were of mixed backgrounds involving predominantly Yorkshire, Red Duroc and Hampshire breeds, with occasional regional interbreeding with Idaho Pasture pigs and Kunekunes, which have pigmented skin. Notably, Hampshire breeds are known to exhibit banded pigmentation in their skin. As such, most skin we studied was unpigmented, but some piglets or adults had pigmented skin or spots (as visible in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5c). Every effort was made to collect skin samples from both males and females across all time points. Adult male skin (6 mo/7 mo) collected from local farmers and butchers was from animals presumably castrated before weaning to avoid boar taint in the meat. Owing to the opportunistic nature of these collections, it is unknown whether postbutchering biological replicates were derived from the same or different litters. Ages were approximated. Postnatal Yucatan miniature hairless pig and Hanford miniature pig skin samples collected from the upper back along the dorsal midline were received from Sinclair Biosciences, and Mangalitsa pigs were raised on farms, with samples collected from the upper back along the dorsal midline following butchering, and were exempt from Washington State University IACUC approval. EDA-KO pig42 samples were collected from the backs of one litter of pigs at P5 or age-matched at 5 mo by the Welsh and Ostedgaard laboratories at the University of Iowa under University of Iowa IACUC-approved protocols (3071121) and shared upon request. All experiments followed relevant guidelines and regulations of the appropriate ethics committees, as detailed where relevant. A visual summary of tissue sample collection sites can be found in Extended Data Fig. 2a. For all animal tissue sample collections, an individual organism was considered to be one biological replicate. Multiple samples may have been collected from one biological replicate, but these were used only as technical replicates. Unless otherwise specified, tissue samples were fixed in 4% PFA overnight and processed for paraffin embedding as described above, or fixed in 4% PFA, washed in PBS and then embedded in OCT (Fisher) before cryopreservation at −80 °C. Epidermal whole mounts were collected using a process similar to that described in previous studies65.

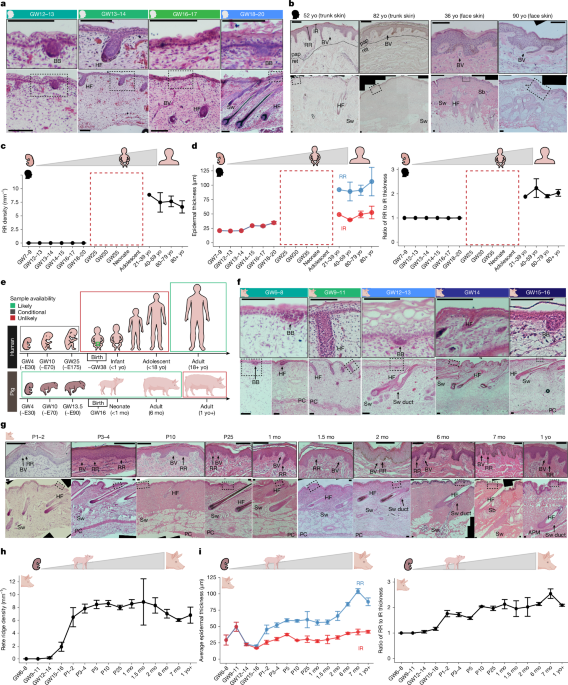

Histological analysis

Paraffin-embedded tissue samples were sectioned at 5 μm (Lef1-eKO back skin) or 10 μm (all others) and stained either with H&E according to standard protocols or using Herovici’s polychrome in a process adapted from previously published protocols66. Coverslips for H&E-stained tissue were mounted using Permount Mounting Medium (Fisher), and those for Herovici-stained tissue were mounted using DPX (Sigma). Slides were bright-field imaged using a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi3 colour camera. Dolphin cryo samples were sectioned at 10 μm, fixed for 30 min at room temperature, washed 3 times with PBS, and rinsed in tap water for several minutes before staining with H&E or Herovici’s polychrome, as above. Dolphin H&E and Herovici slide coverslips were mounted in DPX and imaged using a Keyence BZ-X810 wide-field microscope. K14-CreERT experiment digit samples were sectioned at 13–15 μm using a Leica cryostat and H&E stained using standard protocols.

Hair density assessment

The surface of skin samples was imaged using an AmScope dissecting microscope with an AmScope colour camera before further processing for paraffin embedding or cryopreservation. Multiple distinct images were captured per biological replicate and treated as technical replicates when skin samples were of sufficient size or quantity. Owing to the surgical discard nature of adult human samples collected in this study, many samples were not large enough to allow accurate assessment of hair density or were collected before the beginning of the hair density assessment, hence the smaller sample size in Fig. 2d (n = 8) compared with Fig. 2c. Hair density was also quantified from samples across more anatomical sites, including trunk skin (n = 4), face skin (n = 2), scalp skin (n = 1), and from the base of the nose, which we considered separate from face skin (n = 1).

Porcine wound healing

One litter of neonatal pigs was housed with their mother at Washington State University, were anaesthetized, and received 2.5 × 2.5-cm-square full-thickness wounds under aseptic conditions in accordance with WSU IACUC-approved protocols (6492). Following surgery, piglets were returned to their mother, and the wound site was periodically imaged to assess the size of the wound across the surgery cohort of seven littermates of mixed sexes. Twenty-eight days postwounding (28 dpw), two littermates were euthanized, and the wound site was collected for histological analysis, followed by two more at 43dpw, and the final three at 58dpw. Collected wounds were fixed in 4% PFA for several hours, washed in PBS, then embedded and frozen in OCT at −80 °C.

Porcine BrdU labelling

One litter of neonatal pigs was housed with their mother at Washington State University and injected intraperitoneally twice daily for 3 days from P5 to P7 with 50 mg kg−1 of BrdU (AdipoGen Life Sciences, CDX-B0301-G005) dissolved in sterile saline, in strict compliance with WSU IACUC-approved protocols (6492). One piglet was injected with sterile saline only and was considered a negative control. Three BrdU-injected piglets were euthanized, and tissue was collected from the upper back along the dorsal midline for histological analyses at each of three time points: P8 (1 day postinjection, 1 dpi), P12 (5 dpi) and P16 (9 dpi), along with one negative control individual at P16.

Immunofluorescence analysis of cryo-preserved tissues

For immunostaining of cryo-preserved tissues, frozen tissue samples were sectioned at 60 μm in a Leica cryostat, and staining was performed as described previously67. Tissues were stained using the following primary antibodies: Human-ITGA6 rat (1:200, BD Biosciences, catalogue no. 555735, clone GoH3, lot no. 8136528, 3055226, 1214287, 1033227), human LEF1 rabbit (1:200, Cell Signaling, catalogue no. 2230S, clone C12A5, lot no. 8, 9), human-aSMA rabbit (1:1,000, Abcam, catalogue no. ab5694, clone proprietary, lot no. 1038192-2), human-PDGFRA goat (1:250, R&D Systems, catalogue no. AF307NA, clone P16234, lot no. VG0721111) in pig and marmoset samples, mouse-PDGFRA goat (1:250, R&D Systems, catalogue no., clone P26618, lot no. HMQ0222061) in mouse samples, human-KRT10 rabbit (1:250, Dennis Roop), human-KRT15 chicken (1:250, BioLegend, catalogue no. 833904, clone Poly18339, lot no. B353424, B404683), mouse-SOX9 rabbit (1:1,000, EMDMillipore, catalogue no. AB5535, clone P48436 C-term, lot no. 3677685), human-MKI67 rabbit (1:400, Cell Signaling, catalogue no. 9129S, clone D3B5, lot no. 3, 9), BrdU rat (1:200, Abcam, catalogue no. ab6326, clone BU1/75 (ICR1), lot no. 1009715-43, 1009715-48), human-KRT15 rabbit (1:200, Sigma, catalogue no. HPA024554, clone APREST75794, lot no. A119308), human-SMAD1 goat (1:200, R&D, catalogue no. AF2039, clone Q15797, lot no. KOE062503A), human-pSMAD1/5 rabbit (1:200, Cell Signaling, catalogue no. 9516, clone 41D10, lot no. 10), human-KRT14 rabbit (1:250, Dennis Roop), human-KRT14 mouse (1:1,000, R&D, catalogue no. mab3164, clone LL001, lot no. WEY0823012), human-PDGFC goat (1:200, R&D, catalogue no. af1650, clone Q9NRA1, lot no. JDI022406A), mouse-PECAM1 rat (1:200, Thermo Fisher, catalogue no. 12-0311-82, clone 390, lot no. 1989060, 3095164), mouse-PDGFC rat (1:200, R&D, catalogue no. mab1447, clone Q8Cl19, lot no. HYQ022406A). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488) anti-rat (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A21208, clone AB_2535794, lot no. 2482958, 2668657, 2180272), AF488 anti-chicken (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A11039, clone AB_2534096, lot no. 1899514, 2941307), AF488 anti-rabbit (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A21206, clone AB_2535792, lot no. 1874771), Alexa Fluor Plus 555 anti-rabbit (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A32794, clone AB_2762834, lot no. VK307588, VD297829), AF555 anti-rabbit (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A31572, clone AB_2535849, lot no. 2831376, 2482963), AF555 anti-goat (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A21432, clone AB_2535853, lot no. 1878842, 2400919), AF Plus 555 anti-rat (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A48270, clone AB_2896336, lot no. WF333067, ZG398235), AF647 anti-rabbit (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A31573, clone AB_2536183, lot no. 2544598), AF647 anti-goat (1:1,000, Fisher, catalogue no. A21447, clone AB_2535864, lot no. 1841382, 2297623). DAPI 300 μM stock (1:1,000, BioLegend, catalogue no. 422801, lot no. B222486, B324682) was used alongside secondary antibodies. Slides were imaged using a Leica SP5 or SP8 confocal microscope. Some neonatal pig wound immunostains were also imaged using a Leica DMI8 fluorescence microscope to capture the entire wound section. Dolphin cryo samples were sectioned at 10 μm, fixed in 4% PFA for 30 min, washed in PBS, and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide and 0.8% potassium hydroxide for 5 min until bleaching occurred. Blocking was performed using 2.5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, including antibodies against α-SMA (1:1,000) and keratin 14 (Abcam, ab9220, 1:1,000). After three washes with PBS with Tween-20 (10 min each), sections were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Following three further washes with PBS with Tween-20, coverslips were mounted using VECTASHIELD (H-1200-10) antifade mounting medium. Dolphin immunostains were imaged using an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope. Immunofluorescence images were processed in Adobe Photoshop (v.2021, 2023, 2025).

Immunofluorescence analysis of paraffin-embedded tissues

Paraffin-embedded tissue samples were sectioned at 10 μm, deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated using a decreasing ethanol gradient, and antigen retrieval was performed by immersing slides in boiling 10 mM sodium citrate buffer for 15–20 min. Antibody staining was performed in a process similar to that described above, and images were acquired on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope as described above.

Image analysis and quantification

Numbers of biological replicates for representative histology images and for plots presenting quantifications are included in the figure legends. Images were quantified using Fiji ImageJ (v.1.53c) without blinding. For histological quantifications, human and pig 10-μm H&E or Herovici sections were used to determine epidermal thickness, rete ridge density and apical ridge length measurements. Epidermal thickness was measured from the surface of the epidermis to the base of the rete ridge for rete ridge thickness measurements, and from the surface of the epidermis to the base of the inter-ridge epidermis for inter-ridge thickness measurements. In tissues without rete ridges, rete ridge thickness measurements were not possible, so inter-ridge thickness measurements only were performed and used to construct curves (rete ridge thickness = inter-ridge thickness). This was done to enable calculation of the rete ridge thickness to inter-ridge thickness ratio in R, with rete-ridge-less skin possessing a ratio of 1 and the ratio increasing following the emergence of rete ridges and subsequent increase in rete ridge thickness relative to inter-ridge thickness. Rete ridge density was determined by counting the number of rete ridges and dividing it by the basal length of the interfollicular epidermis over the same region. Multiple measurements for each type of quantification were made per slide, multiple slides were used as technical replicates, and the biological replicate values were reported from an average of the multiple technical replicates for that sample. For developmental quantification of human histology in Fig. 1, fetal trunk skin samples and adult trunk and face skin samples were used. For comparison of trunk skin between species in Fig. 2c, only adult human trunk skin samples were used. For quantification of hair density, the total number of hair follicles in a defined area of the sample was divided by the area assessed. Yucatan hairless pigs had a hair density too low to quantify; there were too few hair follicles present in collected samples to enable accurate assessment of hair density. For Lef1-eKO mouse quantifications, WT phenotype and Lef1-eKO littermates were compared with respect to hair density, and histology quantifications were compared across genotypes; see the legend of Supplementary Fig. 1 for complete details. For quantitative comparison between P5 pig EDA-KO and WT rete ridge density, one litter of P5 EDA-KO pig skin samples from University of Iowa were compared to one litter of P5 WT pig skin samples collected at Washington State University. Rete ridges were quantified in the fingerpads of randomly selected biological replicates from three different litters of P21 WT versus Lef1-eKO littermates, one experiment involving 3 mo WT versus K14-Noggin mice, and one experiment with P56 tamoxifen-treated K14-CreERT;Bmpr1afl/fl versus tamoxifen-treated K14-CreERT (control) mice to assess differences in rete ridge density. Rete ridges are generally concentrated in the distal tip of the fingerpad, beneath the nail, where there are fewer sweat glands. For quantification of scar size, the hairless, pigmentless scar area in the centre of the wounded area was calculated by tracing surface images of the scar using Fiji. For quantification of neonatal pig wounds, immunofluorescence images were quantified in Fiji as described above, using multiple technical replicates (different stained 60 μm sections) per biological replicate. For proliferation and BrdU analyses, MKI67 and BrdU were quantified in Fiji from immunofluorescence images by counting the number of MKI67+ cells in the basal and suprabasal layers per rete ridge or inter-ridge domain. Similarly, BrdU+ cells were counted for each cell layer in the epidermis per rete ridge or inter-ridge domain. It is possible, owing to the dynamic architectural remodelling that occurs during rete ridge formation, that cells within the rete ridge versus inter-ridge boundaries do not represent fixed populations. However, we did not observe signs of lateral migration of BrdU-labelled cells between domains, consistent with previous studies43. Biological replicates were pooled from multiple litters across our collective developmental and BrdU studies owing to difficulty in obtaining pig tissue samples.

Histology and hair density quantification visualization

All quantitative data were graphed using the ggplot package (v.3.4.0) in R (v.4.2.2) with the geom_box() and geom_line() functions for box plots and line plots, respectively. Error bars in line plots represent the standard error of the mean. Hair density and epidermal measurement associations were visualized using geom_line() with addition of a fit line based on a y ~ log2(x) function using the generalized additive model smoothing method in the stat_smooth() function. Individual data points were included on all box plots using the geom_point() function.

Generation of single-cell suspension from pig skin for scRNA-seq

Skin from E90, P3, P10 and 6 mo pigs was collected under approved protocols and processed to generate a single-cell suspension from the epidermis and dermis as described previously68. In a modification to the aforementioned protocol, we added elastase (Worthington Biosciences), hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich) and collagenase IV (Worthington Biosciences) to the dermal digestion solution. All porcine epidermal and dermal single-cell suspensions were mixed 1:1 and processed for 10x Genomics scRNA-seq 3′ V3 Kit to generate scRNA-seq libraries.

Pig scRNA-seq processing and reanalysis of previously published datasets

Pig scRNA-seq libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq PE150 by Novogene. Fastq files were aligned to the Sscrofa.11.1 genome assembly69 (NCBI RefSeq GCF_000003025.6) using 10x Genomics Cell Ranger (v.6.0.0). Cell Ranger outputs were used in downstream analyses. Previously published scRNA-seq datasets were obtained from the GEO or EGA repositories for the respective publications12,26,35,36 (see our GitHub (https://github.com/DriskellLab/Thompson-et-al.-2025) for more details).

scRNA-seq analysis

We analysed our pig scRNA-seq datasets and reanalysed previously published human and mouse scRNA-seq datasets12,26,35,36 using the Seurat package70 in R. We used standard quality control metrics to filter out low-quality cells, normalized and scaled data using SCTransform, and performed dimensional reduction using UMAP with the SLM algorithm to identify clusters. We annotated clusters on the basis of canonical markers for the cell lineages present in skin alongside differential gene expression analysis, as we and others have described previously12,26,27,28,35,36,71,72,73. In brief, basal keratinocytes expressed high levels of KRT15, ITGA6, ITGB1 and KRT14, whereas differentiating keratinocytes expressed low levels of these basal markers and high levels of KRT10, KRT1 and CALML5 (Supplementary Fig. 2c,f,h,j). Dermal fibroblasts broadly expressed PDGFRA and COL1A1/COL3A1, and papillary fibroblasts were resolved at each time point by their expression of the papillary fibroblast markers APCDD1, AXIN2 and CRABP1 and lack of expression of the dermal papillae fate markers LEF1 and ALX4 (refs. 3,27,28,36; Supplementary Fig. 2c,h). Pericytes were identifiable by expression of RGS5 and ACTA2, blood vessels by expression of PECAM1 and CDH5, and lymphatic vessels by expression of LYVE1, VEGFR3 (also known as FLT4) and CCL21 (refs. 28,74; Supplementary Fig. 2c,h). Several subpopulations of sweat gland cells, including ductal and secretory components, were identifiable; these were characterized either by KRT14 and VIM coexpression or SOX9 expression for ductal cells13, or expression of KRT18, CHIA, PHEROC and ACTA2 for secretory coil cells3,14 (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs. 2c,h and 3a,b). In addition to its expression in sweat glands, SOX9 was expressed in outer root sheath keratinocytes, consistent with findings of previous studies52 (Supplementary Figs. 2c,h and 3a,b). LHX2 was also used as a hair follicle keratinocyte marker75 (Extended Data Fig. 5g). We also identified melanocytes and nerve cells by SOX10 and immune cells by PTPRC (Supplementary Fig. 2c,h). The DotPlot() function from Seurat was used to visualize expression of representative marker genes used to define cell types in the UMAP. MKI67 (ENSSSCG00000026302 in porcine datasets owing to genome annotation and renamed MKI67 in figures) was also used to identify dividing cell states.

For integration of porcine epidermal scRNA-seq data for E90, P3, P10 and 6 mo basal cells, basal keratinocyte clusters, defined by high expression of KRT14/15 and not SOX9, KRT10 or other sweat gland markers, were subsetted from each of the individual datasets and merged in Seurat using merge(). Merged datasets were renormalized using SCTransform. For integration of postnatal porcine interfollicular epidermis clusters and P3, P10 and 6 mo keratinocyte clusters, only keratinocyte clusters that did not express sweat gland or hair follicle markers were included. For integration of porcine dermis, E90, P3, P10 and 6 mo papillary fibroblast, pericyte and vascular clusters were subsetted from the individual datasets and merged in Seurat as described above. The P3–P10–6 mo interfollicular epidermis and E90–P3–P10–6 mo dermal integrations also included Harmony batch correction using RunHarmony76. For full details, see our GitHub (https://github.com/DriskellLab/Thompson-et-al.-2025).

The postnatal integrated interfollicular epidermis keratinocytes were also converted from a Seurat object to a CDA object using the SeuratWrappers package to perform pseudotime analysis in Monocle3 (ref. 77). Pseudotime trajectories from non-dividing basal to differentiating states across this dataset were defined with a root in non-dividing basal keratinocyte clusters, which is included on the UMAP-projected pseudotime plots in the figures for reproducibility. To generate line plots of gene expression across pseudotime trajectories, pseudotime gene expression by cell matrices was extracted and converted to a dataframe for visualization of pseudotime gene expression trajectories in ggplot using the geom_line() function accompanied by a trendline generated with the stat_smooth() function using the generalized additive model method and a y ~ x formula.

To generate cluster-level gene expression heatmaps, the ComplexHeatmap package78 in R was used. For FeaturePlots for which the gene was not detected in any cell in the dataset, a blank FeaturePlot with the caption ‘Gene not detected in this dataset’ was created using Adobe Illustrator.

Stereo-seq analysis

First, 4%-PFA-fixed frozen cryo skin samples from P3, P10 and 6 mo pigs were sectioned at 10 μm for use with a Complete Genomics Stereo-seq T FF v.1.2 kit and sequenced using a DNBSEQ-T7. The pig reference genome for SAW (8.1.1) was prepared using the Sscrofa11.1.112 release from Ensembl and the makeRef function. Next, we used SAW count to generate gene expression matrix files. We manually aligned the gene expression matrix on to the tissue mask using Stereo Map 4 and slightly cropped the tissue mask area of each dataset to enable downstream analysis on our local hardware. Then, we ran SAW realign on the cropped tissue mask image and previous SAW count outputs to obtain the processed stereo-seq tissue mask image and gene expression files used in downstream analysis. SAW realign Visualization output.gef files were loaded into Stereopy (1.5.0) in Python (3.8.20) using read_gef() and bin_size = 20. Data underwent quality control filtration and were normalized using sctransform. Clustering was performed using the Leiden algorithm with resolutions of 1.2 (P3), 1.0 (P10) and 1.0 (6mo). Leiden clusters were assigned cell types on the basis of their spatial expression of canonical markers (‘scRNA-seq analysis’) using spatial_scatter_by_gene(), find_marker_genes(), and the spatial localization of the cluster on the tissue mask image with the cluster_scatter() function. All source code is publicly available at GitHub (https://github.com/DriskellLab/Thompson-et-al.-2025).

Cell–cell communication analyses

CellChat44,79 analysis was used to infer pathway and ligand–receptor interactions among core basal and dividing keratinocyte, papillary fibroblast, pericyte and blood vessel clusters from the E90, P3, P10 and 6 mo porcine skin scRNA-seq datasets in parallel, following the standard CellChat pipeline with the human ligand–receptor database to infer cell–cell communication between these cell groups. For pathways or ligand–receptor pairs not identified as a significant interaction by CellChat, based on the default software threshold of P < 0.05 set by the thresh = 0.05 argument in functions like netVisual_aggregate() and extractEnrichedLR(), an empty CirclePlot with the caption ‘Interaction Not Predicted’ was created using Adobe Illustrator. Other epidermal- or dermal-resident cell types may also contribute to rete ridge formation and maturation, including nerve cell endings and immune cells25,35,49,56,59,80; these were beyond the scope of the current study. For the porcine Stereo-seq datasets, Spatial CellChat was used to infer biologically realistic interactions involved in cell–cell communication at cellular resolution on the basis of spatial locations at P3, P10 and 6 mo. Spatial CellChat constrains interactions to biologically realistic distances using the maximal range of molecular diffusion or contact. For secreted signalling, the maximal possible molecular interaction range is the ideal transport distance for small diffusible molecules in a free medium (250 μm by default); for contact-dependent signalling, interactions are restricted to those of molecules in direct contact with each other. The outgoing communication score is defined as the sum of communication probabilities for all outgoing signals, reflecting the role of the cell as a signal sender. Conversely, the incoming communication score is the sum of incoming communication probabilities, representing the role of the cell as a signal receiver. Spatial plots visualizing overall outgoing and incoming secreted signalling strength were constructed for all Leiden clusters from the stereo-seq datasets. Spatial plots visualizing pathway and ligand–receptor-level signalling strength were constructed for a subset of the Stereo-seq data comprising Leiden clusters that were classified as epidermal keratinocyte, papillary fibroblast and vascular clusters: clusters 16, 11 and 6 from P3; clusters 18, 16, 9, 3 and 17 from P10; and clusters 2, 7, 4, 5, 14 and 6 from 6 mo. To provide a visual estimate of the epidermal–dermal junction in Spatial CellChat plots, the bottom boundary was traced beneath the keratinocyte Leiden-clustered spots in Adobe Illustrator using the pen tool and then aligned and superimposed at 50% opacity over the Spatial CellChat plots in Adobe Illustrator (v.2023, 2025). Spatial CellChat plots visualizing pathway and ligand–receptor signalling strength in Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Figs. 9–12 were uniformly contrast adjusted by −100% in Adobe Photoshop (v.2023, 2025) to improve readability between the light blue and purple values from the outgoing and merged colour palettes compared with the grey base spot colour.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in R (v.4.2.2). Sample sizes are listed in the relevant figures and figure legends. No sample size calculations were performed. A minimum of three or more biological replicates, and a mix of males and females, were obtained when possible. However, at some time points, our human or pig sample sets only consisted of one or two biological replicates owing to model limitations (such as initial pig litter size); these are noted in the figure legends. In mouse experiments, multiple litters and a mix of male and female individuals was used when possible; specifics are included in the figure legends or Methods. In pig experiments, multiple litters were used when possible. Sample sizes in this study were comparable with those used in other studies in the field. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate significance; individual P values are given in figure legends. Each experiment was performed once, and no data points were excluded from statistical analysis. In cases in which we could not analyse all littermates from the same litter (for instance, owing to breeding strategy; Fig. 5d), biological replicates were selected randomly for analysis. Hair density and epidermal measurement correlations were computed using the summary() and lm() functions with the log2 formula. The adjusted coefficient of determination (adjusted R2) and P values are reported in the figures. Zoo histology quantifications, pig wound quantifications between time points, and WT/Het/Lef1-eKO histology quantifications were analysed using one-way analysis of variance with the aov() function plus post hoc Tukey’s HSD using the TukeyHSD() function. WT/EDA-KO pig comparisons, rete ridge versus inter-ridge domain MKI67 and BrdU comparisons, and fingerpad rete ridge or sweat gland density comparisons were performed using Welch’s two-sample t-test with the t.test() function.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.