Pyramidal neurons, a type of nerve cell, from the brain’s cerebral cortex.Credit: Juan Gaertner/Science Photo Library/Getty

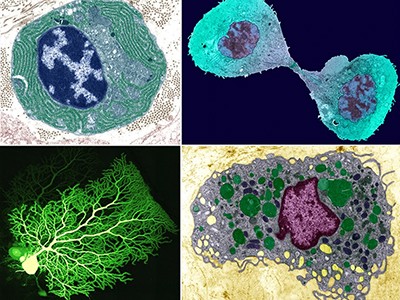

There’s nothing like a challenge. In 2016, biologists Aviv Regev and Sarah Teichmann launched an initiative with around 100 other scientists. They set themselves the monumentally ambitious goal of cataloguing every cell type in the human body, from development to old age1. That amounts to mapping the body’s estimated 37.2 trillion cells. The task was made even more complex by the fact that cells don’t sit still, waiting to be recorded. They continually change as a result of factors including ancestry, geography, gender and age — indeed, life itself.

The Human Cell Atlas: towards a first draft atlas

This week, that initiative, the Human Cell Atlas (HCA), is releasing a collection of studies that represent a significant step towards assembling a first draft atlas. Thanks to some 9,000 donors around the world, the HCA teams now have data on around 62 million human cells, categorized according to 18 biological networks — including maps of cells in the nervous system, lungs, heart, gut and immune system.

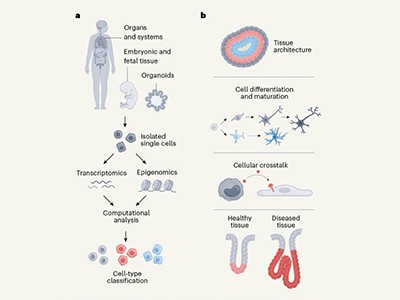

Why is this work needed? Cells are the basic building blocks of living things. The atlas offers to boost researchers’ understanding of how the body works — in health, but also, importantly, in disease. Knowledge of where particular cells are located, combined with in-depth information about the genes they express and the epigenetic markers they carry, is revealing new insights into biology and disease.

Findings from researchers working on the lung cell atlas, for example, highlight the differences between the lungs of a sample of people in Malawi who died from COVID-19 and those who died from other lung diseases2. Scientists have also been studying the development of organs during gestation, for example, through analyses of prenatal human skin3 and developing joints and craniums4.

Cellular atlases are unlocking the mysteries of the human body

The HCA would not have been possible without earlier projects, notably the Human Genome Project and, more recently, the NIH BRAIN Initiative, as well as ENCODE, a project to build a ‘parts list’ of functional elements in the human genome. The HCA teams have also worked hard to reflect human diversity in their data. The consortium includes scientists from Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East5. Researchers from these regions were invited not only to join, but also to help lead and coordinate HCA projects, and to do so according to priorities relevant to local populations. The initiative now involves more than 3,000 scientists across some 1,700 institutions, recording and studying data from people in around 100 countries.

The findings are, the researchers say, the beginning of a journey towards a first draft. There’s a long way to travel between mapping 62 million cells and mapping one billion, let alone trillions. For the HCA to succeed, its funders must remain committed for the long term. These include public funders, such as the European Commission and the US National Institutes of Health, and philanthropic organizations, such as the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Wellcome.

Various metaphors have been used to describe the atlas: some have called it the ‘Google Maps of the human body’, others ‘the periodic table of cells’. It is also a Wikipedia for cells — a bottom-up and open resource, established and run by the scientific community, and the researchers leading its development intend it to remain open access in the long term. And that means continued funding will be essential.

What is a cell type, really? The quest to categorize life’s myriad forms

Most research projects — including those involving large-scale consortiums — have a limited lifespan. Ten years is considered generous. A handful of projects might last a few years longer. Permanent funding tends to be reserved for projects of national or international importance, including essential infrastructure — the tools and technologies without which vital discoveries and inventions would not be possible. That is what the HCA needs to be compared to.

“While genetic studies have mapped more than 100,000 disease-associated variants in the human genome, we do not know in which cells the majority of these variants are active,” HCA researchers write6. Without this knowledge, they add, “we cannot fully understand biology, study more powerful models of disease, deploy better diagnostics, and develop more effective therapies”.

The HCA teams have made a strong start, but the project is an ultra-marathon, not a sprint. If its goals are to be realized, scientists and funders around the world must double down on their commitment.