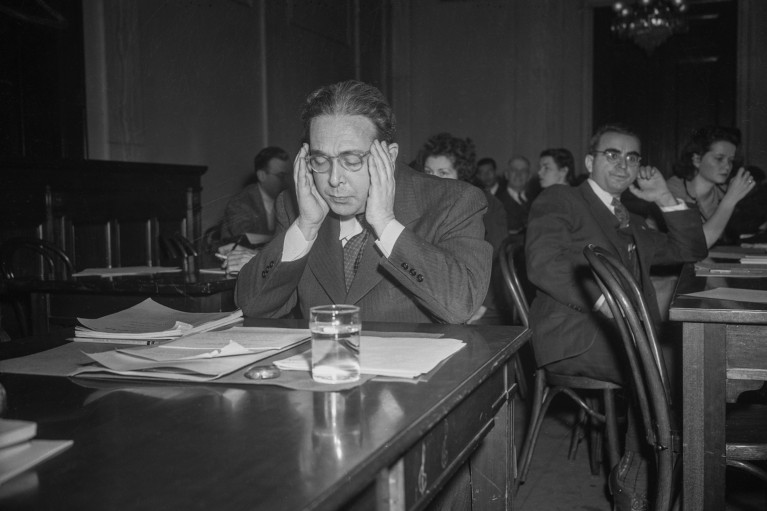

The Hungarian-born physicist Leo Szilard was the inspiration behind the idea of the Szilard point, a term used in cost–benefit analyses of grant proposals. Credit: Bettmann/Getty

Competition is a constant fixture of academic life. We compete for positions, promotions, publications and presentations. And we also compete for money, a necessary requirement if we are to continue taking part in the academic endeavour.

I spent the early years of my PhD at an Austrian non-academic research institute, where competing for grants was the only way that my colleagues and I could secure funding for our research. Everything else we did, from publishing papers to presenting at conferences, felt designed, ultimately, to help secure the next grant. The system seemed back to front: surely it should be about the science first?

Five important financial moves for PhD students

In science, there are many more people with ideas than there are public resources to support those ideas, which raises an unavoidable question about how to allocate scarce resources. Determining the best way to do so is extremely difficult. In an egalitarian approach, everyone would receive an equal share, even if that was only a fraction of what their projects would need. An alternative would be to use strict merit criteria, or to allow institutions to decide how they want to distribute resources. Yet the approach that has become most widespread is competition, which is presented as efficient, fair and reliable.

Million-dollar questions

My main research focuses on using computational tools to analyse intelligent systems, but I have found myself increasingly questioning how the ways in which we fund science shape its outcomes1. Which funding schemes encourage researchers to pursue high-risk research? How do different funding schemes affect scientists themselves, and what ethical issues arise from them?

I suspect that because competition had been a constant companion on my path to becoming a professor at the Vienna University of Technology (perhaps even paving the way), I developed a particular interest in analysing its implications. These questions are core topics in metascience, which takes a bird’s-eye view of how research is done and aims to improve its quality, integrity and efficiency. Like many of my colleagues, I work on these topics alongside my main research.

Link Introducing the j-metric: a true measure of what matters in academia

A concept known as the Szilard point helps to contextualize the issues arising from excessive competition for grants. Named after the Hungarian-born physicist Leo Szilard, who wrote a short story satirizing the bureaucratic nature of scientific funding, this metric describes the threshold at which the total cost of competing for a grant equals (or surpasses) the value of the available funding. These costs are incurred by scientists in writing proposals, by their peers in reviewing them and by the administrative systems that run the process. The question is, which costs more: the research being funded, or the application process itself?

GenAI for Africa, a funding call from the European Union’s Horizon Europe programme, probably crosses that threshold. The initiative aims to use generative artificial intelligence to address the societal challenges that many African countries are facing. With a total budget of €5 million (US$5.8 million), the call, which closed in October, invited proposals across four vast domains — agriculture, health care, urban planning and education. Out of 215 submissions, only two projects are expected to be funded, giving a success rate of under 1%.

To approximate the overall costs associated with the application process, I used two scenarios. See ‘GenAI for Africa: estimated grant-application costs’.

Scenario A

In 2023, group of researchers at the University of Lübeck in Germany developed a simulation tool for estimating the costs of grant funding. To arrive at cost estimates for GenAI for Africa applications, I fed this simulation with data from the Interim Evaluation of the Horizon Europe Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2021–2024). The key inputs are:

Time investment. According to the report, “the median consortium coordinator spends … 36 to 45 person-days per proposal. The effort for contributing consortium partners is typically lower, spending 16 to 25 person-days.”

Consortium size. The average consortium size for Horizon projects is likely to be between 12 and 16 partners, according to statistics published by the European Commission.

Hourly payment rate of applicants. Hourly rates vary considerably depending on country, sector (industry versus academia), seniority and applicable overheads. To reflect this diversity, I drew on several reference sources from across Europe. To account for differences, I assumed the average cost of an hour’s work to be between €20 and €60.

The variation in input values enabled me to produce two cost estimates for GenAI for Africa grant applications: a lower estimate (Scenario A1) and a higher estimate (Scenario A2).

The tool automatically accounts for decision-making and administrative costs.