TSS selection

The selection of relevant TSSs was done as previously described60. In brief, we selected GENCODE-defined TSSs62, with the additional requirement that they are active in at least one cell type or tissue according to the FANTOM5 database63. This process resulted in a curated set of 30,607 TSSs.

Genome-wide MPRA dataset

The initial PARM models for HepG2 and K562 cells were trained using publicly available genome-wide MPRA data (GEO accession GSE128325). We combined the fragments from all the libraries and retrieved those overlapping a window of −300 bp to +100 bp relative to the 30,607 TSSs.

Construction of MPRA libraries

Focused library using DNA fragmentation and capture-based methods

To generate the focused library, 100 µg DNA was isolated from a human cell line (HG02601) using an Isolate II Genomic DNA kit (Bioline, BIO-52066). The isolated DNA was then fragmented using dsDNA Fragmentase (NEBNext, M0348L) for 30 min and subsequently size-selected by gel extraction for fragments sizes ranging from around 200 to 400 bp. DNA was end-repaired using an End-IT DNA End-Repair kit (Lucigen, ER81050) and subsequently A-tailed using Klenow Fragment (3′→5′ Exo-; NEB, M0212M). For cloning purposes, two custom 31 bp dsDNA adapters (oNK46 and oNK47) containing a T-overhang for the 5′ and 3′ ends of the fragments were ligated to the fragments using TA-ligation with a Quick Ligation kit (NEB, M2200L; see Supplementary Table 1 for oligonucleotide sequences). These adapters contain overlaps with the 3′ and 5′ ends of the linear barcoded p101 vector (see ref. 22) to allow Gibson assembly of the fragments after hybridization. PCR amplification was performed using eight cycles with the primers oNK51 and oNK52 and Equinox polymerase (Twist, 104176). To capture the promoter region of the TSS, we selected 30,607 TSSs and their −300 to +100 bp window and ordered a high stringency hybridization capture library from Twist for these custom regions consisting of 127,575 probes. To prevent nonspecific binding of probes to our fragments, we designed custom blockers complementary to the custom Gibson adapters (oNK57 and oNK58). Fragments were captured using the custom hybridization panel according to the manufacturer’s protocols. In brief, 1 µg fragments were hybridized to the custom hybridization panel for 16 h in the presence of specific (custom designed) and nonspecific (COT-1 DNA) blocker solution. Subsequently, hybridized fragments were enriched using streptavidin binding and amplified using the primers oNK51 and oNK52 using PCR for nine cycles. Captured fragments were purified and cloned into the linear barcoded p101 vector with Gibson assembly using HiFi DNA assembly master mix (NEB, E2621L) for 60 min at 50 °C. The Gibson assembly mix was then purified and subsequently transformed into MegaX DH10B ultracompetent bacteria (Thermo, C640003) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Transformed bacteria were grown in LB overnight and the plasmid library was isolated using a Gigaprep Isolation kit (Thermo, K210009XP).

Oligonucleotide-based libraries

All three synthetic libraries (synthetic promoters, ISM and motif insertions) were generated using synthetic oligonucleotides that were ordered from Twist. The oligonucleotide library was ordered from Twist and amplified using KAPA HiFi Hotstart Readymix (Roche, KK2601) for 14 cycles using oNK69 and oNK71. The library was bead-purified, end-repaired using an End-IT DNA End-Repair kit (Lucigen, ER81050), subsequently bead-purified and digested with EcoRI-HF (NEB, R3101S) and NheI-HF (NEB, R3131S) for 1 h at 37 °C. Fragments were ligated in NheI-HF/EcoRI-HF double-digested vector (an adaptation of the p101 vector64) using T4 DNA ligase (Roche, 10799009001). The ligation mix was purified and transformed as described above.

Cell culture and transfection

Cell lines K562 (ATCC-CCL 243), U2OS (ATCC HTB-96), HCT116 (ATCC CCL-247), LNCaP (ATCC CRL-1740), HepG2 (ATCC HB-8065), HEK293 (ATCC CRL-1573), MCF7 (ATCC HTB-22) and AGS (ATCC CRL-1739) were all obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The HAP1 cell line was obtained from T. Brummelkamp, who generated this cell line65. Given the verified sources, the cell lines were not re-authenticated. All cells in culture were regularly tested for mycoplasma. K562 cells were cultured in RPMI1640, HepG2, MCF7 and HEK293 in DMEM, HCT116 and U2OS in McCoy5a, LNCaP and AGS in RPMI1640, and HAP1 in IMDM with 1% glutamine and 25 mM HEPES. All media were supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo). All cells were transfected as previously described22, except that HCT116, LNCaP and MCF7 were transfected using nucleofector programs D-032, T-009 and P-020, respectively, and HEK293 and U2OS were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 or 3000. HAP1 was transfected using Xfect reagent (Takara, PT5003-2). For each biological replicate of the focused library, 10 million cells were used, except for the experiment that used K562 cells, in which 50 million cells were used. For each biological replicate of any oligonucleotide-based library, 5 million cells were used.

Organoid culture

The CRC organoid was derived from surgical resection and was established as previously described66,67. Sampling was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Netherlands Cancer Institute–Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital (NL48824.031.14) and written consent was obtained from the patient. The use of human material or data for the current project was approved by the NKI-AVL Institutional Review Board and registered under number IRBdm23-361. In brief, tumour tissue was mechanically dissociated and digested with 1.5 mg ml–1 collagenase II (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μg ml–1 hyaluronidase type IV (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 μM Y-27632 (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were plated in Cultrex RGF BME type 2 (3533-005-02, R&D Systems) and placed in a 37 °C incubator for 20 min before adding CRC complete organoid medium. The medium was used as previously described66, and is composed of Ad-DF+++ (Advanced DMEM/F12, Gibco) supplemented with 2 mM Ultraglutamine I (Lonza), 10 mM HEPES (Gibco), 100 U ml−1 each of penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco), 10% noggin-conditioned medium, 20% R-spondin1-conditioned medium, 1× B27 supplement without vitamin A (Gibco), 1.25 mM N-acetylcysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 mM nicotinamide (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 ng ml−1 human recombinant EGF (Peprotech), 500 nM A83-01 (Tocris), 3 μM SB202190 (Cayman Chemicals) and 10 nM prostaglandin E2 (Cayman Chemicals). Organoids were passaged every week, by enzymatical dissociation with TrypLE Express (Gibco), washed and subsequent embedded in BME. For large-scale organoid expansion, a previously described protocol68 was used. Organoids were authenticated by SNP array, and were tested on a monthly basis for mycoplasma using Mycoplasma PCR43 and a MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection kit (LT07-318).

Organoid electroporation

The electroporation protocol was adapted from a previous study69. In brief, organoids were cultured in regular culture medium and freshly split 2 days before electroporation. On the day of electroporation, organoids were enzymatically dissociated into single cells in TrypLE Express (Gibco) and supplemented with 10 μM Y-27632 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min. The cells were collected using room temperature PBS (Gibco) and spun down at 500g for 5 min. A total of 5 million cells was used per reaction and resuspended in 100 μl room temperature Opti-MEM (ThermoFisher), supplemented with 22 μg of the focused library. For each biological replicate, a total of 50 million cells was used. Electroporation was performed using a NEPA21 system with the following settings: poring pulse values of voltage = 175 V, pulse length = 5.0 ms, pulse interval = 50.0 ms, number of pulses = 2, decay rate = 10% and polarity = +; and transfer pulse values of voltage = 20 V, pulse length = 50 ms, pulse interval = 50 ms, number of pulses = 5, decay rate = 40% and polarity = +/–. Electroporation was carried out in 2.0-mm-gap cuvettes (Cell Projects). After electroporation, 400 μl Opti-MEM supplemented with 10 μM Y-27632 was added on top, followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature. Thereafter, cells were collected using a plastic disposable pipette, spun down at 500g for 5 min and resuspended in regular culture medium (supplemented with 10 μM Y-27632) with 5% BME.

Conditions and treatments

For the heat-shock condition, cells were transfected with the library and placed in an incubator at 37 °C for 24 h. Three hours before collection, cells were transferred to an incubator set at 43 °C and collected 3 h later for RNA isolation. For the chemical perturbations, both nutlin-3a (MedChemExpess, HY-10029) and PMA (ThermoFisher, J63916.MCR) were dissolved in DMSO and used at 8 µM and 1 µM, respectively. The compounds were added directly after transfection and collected 24 h later for RNA isolation.

Library sequencing

Library characterization (barcode-to-fragment association) of the focused library was done by iPCR as previously described22. Library input (pDNA) was also generated as previously described22, except that NcoI-HF was used to digest the plasmid library.

RNA sample processing

RNA was isolated using TRIzol (ThermoFisher, 15596018) and divided into 10 µl reactions containing 2.5 µg RNA per reaction. Per biological replicate, 12 reactions were done in parallel. To each reaction, we added 10 units DNase I for 60 min (Roche, 04716728001), which was subsequently inactivated by the addition of 1 µl 25 mM EDTA and incubated at 70 °C for 10 min. cDNA was generated by adding 1 µl of gene-specific primer targeting the GFP ORF (oNK17) and 1 µl of dNTP (10 mM each) and incubated for 8 min at 65 °C. This reaction was continued by adding 4 µl RT buffer, 20 units RNase inhibitor (Thermo, EO0381), 20 units Maxima reverse transcriptase (Thermo, EP0743) and 2.5 µl water for 60 min at 50 °C, and subsequently heat-inactivated at 85 °C for 5 min. Each reaction was PCR-amplified with MyTaq Red mix (Bioline, BIO-25043) using (index variants of) MMA219 and oNK28. PCR reactions were purified using bead-purification (GC Biotech, CPCR-0500) and subjected to single-read sequencing on Illumina NextSeq or NovaSeq 6000 platforms.

Read processing

Sequencing reads were processed as previously described22. This process resulted in a table with read counts per individual fragment for both cDNA (fragment activity) and either iPCR or pDNA (input, normalization). After converting raw values to reads per million (RPM), we normalized the read counts as follows:

$$\mathrmRatio_\mathrmfragment,\mathrmreplicate=\left(\frac\rmcDNA\; RPM_\mathrmfragment,\mathrmreplicate\rmiPCR\; RPM\right)+Q01(\mathrmratio_\mathrmreplicate)$$

Where \(Q01(\mathrmratio_\mathrmreplicate)\) is the 0.1 quantile of the non-zero observed ratios for that replicate. Then, we defined the fragment activity as follows:

$$\mathrmFragment\,\mathrmactivity=\frac\sum _\mathrmreplicate=1^N\log _2(\mathrmratio_\mathrmfragment)N$$

Where N is the total number of biological replicates.

Model input

PARM takes as input the genomic sequence of a single fragment from the library and predicts the associated promoter activity. This sequence is represented as a matrix of shape (600, 4) representing a one-hot-encoded DNA sequence as follows: A = [1, 0, 0, 0], C = [0, 1, 0, 0], G = [0, 0, 1, 0], T = [0, 0, 0, 1] and N = [0, 0, 0, 0], of length 600 bp. As MPRA fragment lengths vary from 88 bp to 600 bp, we padded sequences shorter than 600 bp with N until reaching the maximum length. The number of N bases padded on the right and left sides of the fragment sequence was randomized for each fragment following a uniform distribution to avoid potential biases towards positions in the middle of the matrix. Moreover, to account for the creation of motifs on the edges of the fragments, we added adaptor sequences from the backbone plasmid. On both edges of each fragment, we included seven nucleotide sequences corresponding to the plasmid backbone. Specifically, for the genome-wide library, these sequences were CAGTGAT and ACGACTG, and for the focused library, they were CAGTGAT and CACGACG.

DL model architecture

The PARM architecture, adapted from the first layers of Enformer10, consists of a CNN with self-attention pooling layers (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Models were constructed individually for each cell type, with hyperparameters optimized according to the Pearson’s correlation between predictions and test set measurements. The first layer comprises a 1D convolution layer of kernel size 7 and filter size 125, followed by a batch normalization, GeLU activation layer and a 1D convolution of kernel size 1 and filter size 125. A skip connection was added between the first 1D convolutional layer and the output of the first layer to feed the subsequent attention layer of filter size 125. After this first block, the following sequential layers were repeated 5 times: batch normalization, GeLU activation layer, 1D convolution layer with skip connection and kernel size 7, padding 3 and filter size 125, batch normalization, GeLU activation, 1D convolution kernel size 1 and filter size 125. The output was concatenated with the skip connection and fed to an attention pooling layer. Finally, there was a global max pooling layer over the position dimension, followed by a dense layer that reduced the input size of 125 to 1, passed through a GeLU activation layer. The model was implemented in PyTorch (v.2.1.1).

Model training and evaluation

We divided the 30,607 promoters into 6 equally sized folds, ensuring that overlapping promoters were assigned to the same fold. We ensured that there was no overlap between sequence fragments across different data folds. To achieve this, any TSS with a nearby TSS within a distance of 2 kb + 600 bp (reflecting the maximum length of the fragments) was assigned to the same data fold. One fold was reserved for final model assessment, whereas the remaining five folds were rotated in a cross-validation fashion. This process involved using four folds for training and one fold for determining the best hyperparameters.

We used a Poisson negative log-likelihood loss function to account for the non-uniform distribution of the promoter activity score or a heteroscedastic loss, following a similar approach used for Basenji270 and Enformer10. The neural network was trained for a total of 10 epochs with a batch size of 128. To optimize the training process, we used the AdamW optimizer71, with a gradual warm-up learning rate starting from 2 × 10−8 that increased linearly for the first 5,000 training batches until reaching 10−4. Subsequently, the learning rate was decreased using a cosine function until the last epoch. Other hyperparameters involved were as follows: weight decay = 0.2, β1 = 10−5 and β2 = 10−5. The model was trained on one NVIDIA Quadro RTX 6000 GPU.

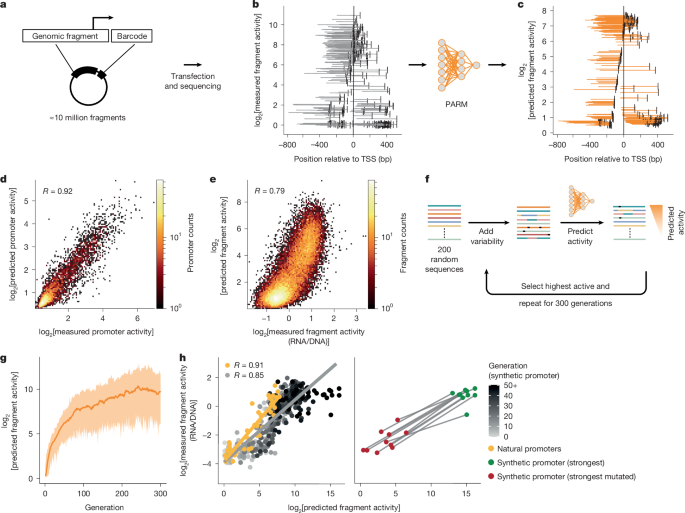

Generating active synthetic promoters

To generate synthetic human promoters with PARM, we used a previously reported genetic algorithm21 but with slight differences. Using the DEAP-ER framework (v.2.0.0, https://github.com/aabmets/deap-er), we set the population size to 200, in which each individual was a randomly generated sequence of 232 bp. We set the mutation probability to 0.8 and the two-point crossover probability to 0.5, and let it run for 300 generations. We used the standard tournament selection operator (sel_tournament) with three individuals participating in each round (contestants = 3), and the evaluation operator was the prediction by PARM for the K562 model. After running ten independent instances of the genetic algorithm, we selected some synthetic and natural sequences (as described below) and cloned them into our reporter library (as described above).

Synthetic promoter library

To validate the predictions of the genetic algorithm, we constructed a synthetic promoter library. For the fragments we selected the following sequences. (1) For each genetic algorithm run, from 13 different generations (every fourth generation starting from generation 0 and up to generation 48), the least, median and maximum predicted active fragment for a total of 390 (10 × 13 ×3) fragments. (2) The most active predicted fragment from each genetic algorithm run (independent of generation) for a total of ten fragments, which we termed as the synthetic promoter (strongest). (3) For each of the most active fragment, we mutated that fragment in silico until only 20% of its predicted activity was left. There were also a total of ten fragments that we termed synthetic promoters (strongest mutated). (4) Control sequences from natural promoters that were selected to have activities ranging from low to high, including the 15 most highly active as measured by MPRA in K562 cells. This library was cloned as described above. Fragment activity was calculated by taking the mean log2[RNA/DNA] ratio of four barcodes. Data are available in Supplementary Data 1.

ISM validation library

The activity of each fragment was calculated by taking the mean of the three barcodes to which each individual fragment was linked. To select a set of promoters and cell lines that were reliably measured, we chose a stringent cutoff value based on autocorrelations. To achieve this, for each position we computed the effect of all mutations as a mean of all mutations. Then, we computed the Pearson’s correlation of each position with the following one, excluding the first and last positions. Promoter–cell line combinations for which the autocorrelation was equal to or higher than 0.5 were kept for subsequent analyses. This resulted in a set of 30 cell line–promoter combinations for which we have reliable data. Data are available in Supplementary Data 2.

Motif insertion library

The activity of each fragment was calculated by taking the mean of the five barcodes to which each individual fragment was linked. Also, a pseudocount of 0.01 was added. Moreover, we required that each fragment is linked to at least 4 barcodes and have a pDNA (input) count of >100. These requirements led to a final 19 promoters with YY1 insertions, 19 for NFYA, 19 for NRF1 and 19 for SP1. Data are available in Supplementary Data 3.

ZNF48 protein expression

A codon-optimized gene block encoding the full-length ZNF48 protein was cloned in a modified pFastBac vector using Ligation Independent Cloning as previously described72 for protein production in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cells. The protein was fused to an amino-terminal 10×His-2×StrepII-tag. Bacmid DNA was prepared, and baculovirus stocks P0 and P1 baculovirus were produced in Sf9 insect cells using the Invitrogen Bac-to-Bac method. Proteins were expressed in Sf9 insect cells cultured in ESF921 medium (Expression Systems). Sf9 suspension cells (1 × 106 cells per ml) were cultured in a shaker incubator at 28 °C at 80 rpm and were infected with the P1 baculovirus stock. Cells were collected 3 days after infection by centrifugation (500g), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20 °C until further processing. The cell pellet was thawed and resuspended in 25 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 1 µM ZnCl2 plus 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% glycerol. Cells were lysed by sonication on ice and debris was removed by centrifugation at 53,340g for 40 min at 4 °C.

Recombinant ZNF48 pull-down from SF9 lysate

Synthetic oligonucleotides containing the 30 bp wild-type TMEM sequence or its mutated counterpart were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies, with 5′ biotinylation on the forward strand. Oligonucleotides were annealed in oligonucleotide annealing buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 2 mM EDTA) by heating to 95 °C for 10 min and gradually cooling to room temperature. For each pull-down, 20 µl streptavidin sepharose bead slurry (GE Healthcare, GE17-5113-01) was equilibrated by washing twice with ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% NP-40, followed by one wash with DNA binding buffer (DBB: 1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA and 0.05% NP-40). The equilibrated beads were then incubated with 500 pmol of the annealed oligonucleotide mixture for 30 min at 4 °C with gentle rotation. Following incubation, the beads were washed twice with DBB and once with protein incubation buffer (PIB: 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.25% NP-40 and 1 mM DTT, supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail). For each pull-down, 1 or 2 mg of SF9 cell lysate expressing recombinant ZNF48 was incubated with the oligonucleotide-bound beads for 90 min at 4 °C with rotation. The beads were subsequently washed five times with PIB and once with ice-cold PBS. Bound proteins were eluted by resuspending the beads in 1× loading sample buffer (Invitrogen, Bolt) containing DTT and heating at 95 °C for 10 min. Debris was removed by centrifugation, and samples were resolved by SDS–PAGE on 4–15% TGX gradient gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred onto a 0.22 µm nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen, iBlot 3.0 transfer stacks) using an iBlot 3.0 system (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked for 30 min at room temperature with 5% non-fat milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T). Membranes were probed overnight at 4 °C with a rabbit polyclonal anti-ZNF48 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, HPA023806). After three washes with PBS-T, membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated swine anti-rabbit IgG IgG-HRP (Dako, P0399) diluted 1:1,000 in 5% milk in PBS-T. Following three additional washes with PBS-T, membranes were imaged using a Fusion Fx imaging system (Vilber).

Cell lysate preparation for mass spectrometry analysis

Crude nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described73. In brief, cells were collected and spun down (400g, 5 min, 4 °C) and the obtained cell pellet was washed twice with ice-cold PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in 5 volumes of buffer A (10 mM HEPES KOH pH 7.9, 15 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM KCl) and incubated for 10 min on ice. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (400g, 5 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in 2 volumes of freshly made buffer A+ (buffer A supplemented with 0.15% NP-40 and EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor). Cells were lysed by dounce homogenization (40 strokes, 30 s rest on ice every 10 strokes), and crude nuclei were collected by centrifugation (3,200g, 15 min, 4 °C). Crude nuclei were washed with ice-cold PBS (10 times the volume of the pellet) and clean crude nuclei were collected by centrifugation (3,200g, 5 min, 4 °C). Crude nuclei were resuspended in buffer C (420 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, supplemented with 0.1% NP-40, CPI, and 0.5 mM DTT) and incubated for 90 min while rotating at 4 °C. Afterwards, the nuclear lysate was centrifuged (20,000g, 30 min, 4 °C) and the soluble nuclear fraction was collected. Obtained nuclear extracts were aliquoted, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

DNA pull-downs

DNA oligonucleotides were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies with 5′-biotinylation of the forward strand. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Oligonucleotides were annealed as previously described74. DNA pull-downs were performed in duplicate as previously described33. In brief, for each reaction, 20 μl streptavidin−sepharose bead slurry (GE Healthcare) was equilibrated by washing once with 1 ml PBS containing 1% NP-40 and twice with 1 ml of DBB. Next, 500 pmol previously annealed DNA oligonucleotides was incubated with the beads in a final volume of 600 μl DBB (30 min of rotating at 4 °C). Beads were then washed twice with DBB and once with PIB. Per pull-down, 500 μg of nuclear extract was incubated with the beads in a total volume of 600 μl PIB (90 min rotating at 4 °C). After incubation, beads were washed 3 times with 1 ml PIB and twice with 1 ml of PBS. Excess PBS was removed using a syringe and beads were immediately resuspended in 50 μl elution buffer (2 M urea, 100 mM Tris pH 8.5 and 10 mM DTT) and incubated for 20 min while shaking at room temperature. Samples were then incubated with iodoacetamide (50 mM final concentration) for 10 min in the dark while shaking. Next, proteins were digested using 0.25 μg trypsin and incubated while shaking for 2 h at room temperature. Afterwards, samples were spun down and the supernatant was collected. Beads were washed once more with 50 μl elution buffer, and the supernatant was collected and added to the previously collected supernatant, 0.1 μg of trypsin was added to the mix and incubated overnight. The next day, samples were purified using StageTips. Dimethyl labelling on StageTips was done as previously described75.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Peptides were analysed by LC–MS/MS on an Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer connected to an Evosep One LC system (Evosep Biotechnology). Before LC separation using Evosep One, peptides were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid and 20% of the sample was loaded on Evotip Pure (Evosep) tips. Peptides were eluted directly on the column and separated using the pre-programmed ‘extended method’ (88 min gradient) on an EV1137 (Evosep) column fused with an EV1086 (Evosep) emitter. Nanospray was achieved using an Easy-Spray NG Ion Source (Thermo) with the spray voltage set to 1.7–2 kV. The Exploris 480 was operated in DDA cycle time mode with 1 s. The duty cycle and full MS scans were collected in the Orbitrap analyzer with 60,000 resolution at m/z 200 over a 375–1,500 m/z range. The default charge state was set to 2+, the AGC target was set to ‘standard’ for both MS1 and ddMS2, and for both scan types, the maximum injection time mode was set to auto. Monoisotopic peak determination was set to peptide, and dynamic exclusion was set to 20 s. For ddMS2, a normalized HCD collision energy of 30% was applied to precursors with a 2+ to 6+ charge state meeting a 5 × 104 intensity threshold filter criterion. Precursors were isolated in the Quadrupole analyzer with a 1.2 m/z isolation window, and MS2 spectra were acquired at 15,000 resolution in the Orbitrap.

Mass spectrometry data analysis

All raw mass spectrometry spectra were processed using Maxquant software (v.2.4.9.0, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry) and searched against the UniProt curated human proteome database released in 2022. Identified proteins were filtered for common contaminants. Dimethyl-labelled samples were analysed using a modified workflow that is based on the built-in dimethylation 3plex method. For quantification, light-dimethyl-labelled peptides (+28.031 Da) and heavy-dimethyl-labelled peptides (+32.056 Da) were used. Low abundance resampling was enabled. Only proteins that were quantified in all four channels were used for downstream analysis. Outlier statistics were used to identify significant proteins. Proteins were considered significant with one interquartile range for both forward and reverse experiments.

ISM assay

As previously described7,10,23,26, ISM involves predicting the promoter activity of a reference sequence and sequences with all possible single mutations at the position of interest. The importance score is calculated as the score of the reference sequence minus the average score of all possible mutations at a single position.

ICGC data

International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) data were obtained from IGCG data portal release 28 (ref. 76), querying whole-genome sequencing as the sequencing strategy and retrieving all donors with data in chromosome 5, from 1,295,152 to 1,295,462 bp in the hg19 reference genome.

Enformer predictions

For the Enformer comparisons, we predicted the variant effect as previously described77. We computed the CAGE outputs for the relevant cell types and log-transformed the predictions. We averaged both strands, the three neighbouring bins around the SNP positions and all available CAGE tracks for the relevant cell lines. As some cell lines in our validation library were missing in Enformer, we used GSS, MKN45, AZ521 and MKN1 to test the AGS cell line, HS-Os-1 for U2OS, CACO-2 and COLO-320 for HCT116, DU145 for LNCaP.

Borzoi predictions

For the Borzoi predictions, we predicted the variant effect as previously described30. We followed the same procedure as described above in Enformer using CAGE. For the missing cell lines, we used GSS, MKN45, AZ521 and MKN1 to test the AGS cell line, HS-Os-1 for U2OS, DU145 for LNCaP, CACO-2 and COLO-320 for HCT116.

Prediction of the direction of effect of cis-acting eQTLs

To evaluate the accuracy of the predicted expression effect of the PARM, Enformer and Borzoi models, we compared the predicted direction of effect with the sign of the measured beta of fine-mapped GTEx v8 cis-acting eQTLs29. From this set, we selected all fine-mapped likely-causal cis-acting eQTLs from whole blood by taking all variants in a credible set with a posterior causal probability (PIP) of ≥0.9 as determined by SuSIE78, in the same strategy as previously defined30. We only considered fine-mapped single nucleotide variants (SNVs), as insertion/deletion effects are more difficult to model and substantially differ from the predicted effect sizes of SNVs. The concordance in direction of effect is defined as follows:

$$\mathrmConcordance\in \mathrmdirection=\frac\sum _i=1^N_\mathrmeQTLs1(\mathrmvariant\,\mathrmeffect_i\cdot \beta _i > 0)N_\mathrmeQTLs$$

Where the NeQTLs indicates the total number of eQTLs (1,836) with a non-zero effect and β indicates the observed eQTL effect as estimated in GTEx. As a baseline comparison, we computed the concordance in direction for random predictions by randomly sampling from a uniform distribution using the random.uniform implementation from NumPy set from −1 to +1 (ref. 79).

Motif scanning and RS identification

Using the Hocomoco (v.11) human database32, we scanned the importance scores of the 30,607 promoters generated by one of the (cell-type-specific) PARM models. Each of these 30,607 vectors, which contain promoter importance scores, were scanned with each information content (IC) motif from the Hocomoco database with a stride of 1. At each position, we computed the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the IC of the motif and the importance score at each position, here referred to as rposition. Moreover, we calculated the mean of the effect scores multiplied by the IC, here referred to as ISposition.

We only retained hits with a rposition equal to or higher than |0.75|. To avoid hits in regions where the importance score was low but still had a R higher than 0.75 (which occurred especially for short and high-content motifs), we applied a second cutoff on the ISposition that accounts for a varying lengths of the motifs and IC, as follows:

$$\mathrmIC\,\mathrmscore_\mathrmpos,n=\frac\mathrmIC_\mathrmpos,n\max (\mathrmIC)\times \mathrmImportance\,\mathrmscore_x \% $$

Where IC scorepos,n indicates the IC of a motif in a specific position (pos) and nucleotide n, and max(IC) is the maximum value of the IC across all positions and nucleotides over that motif. The Importance scorex% represents the xth percentile value of all variant effect scores in all promoters (described above). Thus, IC scorepos,n would represent the minimal motif to consider a hit, at which the most important position would have a value of Importance scorex%. Then, the cutoff value of ISposition is defined as:

$$\rmIS_\rmposition\ge \rmmean(\rmIC\,\rmscore_\rmpos,n\times \rmIC_\rmpos,n)$$

The importance scorex% is calculated separately for each model owing to differences in the range of importance scores between models, as well as separately between activators and repressors. For activators, the 95th percentile is used, whereas for repressors we consider the bottom 5th percentile.

Thus, we consider a RS if a motif in a database survives both cutoffs in rposition and ISposition in the ISM profile.

For the identification of RSs in the measured data, we calculated rposition in the same way, but the ISposition cutoff is imported from the corresponding model, converted to a Z-score and then applied to the measured data. Then, those surviving both cutoffs we consider as measured RSs.

RS distribution comparisons

To establish difference between the RS distribution and generic motif distribution of specific TFs across promoters, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used, which is an omnibus test to establish any difference between two empirical distributions (location, scale or shape). To specifically test for a shift in mode between RS distributions (as for the comparison between activating versus repressive RSs), we leveraged a permutation test. In brief, assignment to an active or repressive class was shuffled, after which a null distribution of the difference between the modes of the repressive RS distribution and the activating RS distribution was established. This null distribution was used to calculate an empirical P value. Modes were determined after smoothing the distribution with a 20 bp sliding window.

Identifying unknown motifs

To identify RS that did not match any known motif, we scanned for patches of at least five nucleotides where all their importance scores were equal to or higher than the Importance score95% for activators or equal to or lower than the Importance score5% for repressors. If there were several consecutive RS separated by a maximum of two nucleotides, they were treated as a single RS. Then, the nucleotide importance of the full RS region was correlated with all motifs in the Hocomoco (v.11) human32 or the Jaspar2024 CORE vertebrates non-redundant database80. If neither database contained a hit with R ≥ 0.75, it was annotated as an ‘unknown motif’.

Clustering motifs to obtain motif families

To cluster motifs separately for the Hocomoco (v.11) human database and for the unknown motifs, we followed previously described methods81. Pairwise similarity scores of position frequency matrices were computed using TOMTOM (v5.4.1) with a minimum overlap of 6 bp and Pearson’s correlation as the distance metric for scoring alignments. Subsequently, we converted these scores to E values by a log transformation, after adding a pseudocount of 1 × 10–8. Hierarchical clustering was then conducted using complete linkage and Pearson’s correlation as the distance metric. The tree was cut at a height of 0.8, and all motifs within the cutoff were considered from the same motif family.

Matching a RS with its TF expression

For further analysis, we exclusively included RSs associated with expressed TFs. Expression status was determined using data from the Human Protein Atlas (v.23.0; accessible at https://www.proteinatlas.org/download/rna_celline.tsv.zip)82. RSs linked to TFs for which ln(TPM+1) ≥ 1 were selected for subsequent analyses.

Consensus motif

We selected the motif with the lowest E value as the representative motif to construct the consensus motif in a cluster in the unknown motifs. For each motif in the cluster, its position frequency matrix was added to the representative motif, considering the optimal offset and orientation reported by TOMTOM. Each position was then normalized by the number of motifs added in that position. If a position in the consensus motif was contributed by less than 30% of the motifs in the cluster, that position was removed.

Sequence scanning

We performed a naive scan of all promoter sequences spanning a region from 250 bp upstream to 50 bp downstream of the TSS using FIMO (v5.4.1)36 with default arguments and the Hocomoco (v.11) human database32.

RS insertion analysis

We performed in silico insertion of YY1, SP1, NRF1 and NFYA motifs in all promoters. For each of these TFs, we inserted three variants: the consensus sequence and two mutated versions as negative controls. We shortened the consensus sequence as defined by Hocomoco (v.11)32 to work in similar motif length ranges. For NRF1, the following sequences were used: consensus, ACTGCGCATGCGCA; mutated 1, ACTGCGTATTCGCA; and mutated 2, ACTTCGAATTGGCA. For NFYA, the following sequences were used: consensus, TCAGCCAATCAGAA; mutated 1, TCAGTCTATCAGAA; and mutated 2, TCATCAGATCAGAA. For SP1, the following sequences were used: consensus, GGGGGCGGGGCCGG; mutated 1, GGGGCCCGGGCCGG; and mutated 2, GGAGGTGGTGCCGG. For YY1, the following sequences were used: consensus, CAAGATGGCGGC; mutated 1, CAAGTTGCCGGC; and mutated 2: CACGAAGACGGC.

The motifs were inserted in 15 positions ranging from 160 bp upstream of the TSS to 63 bp downstream in a fixed step of 14 nucleotides.

Endogenous promoter activity

To obtain an estimate of endogenous promoter activity in K562 cells, we aggregated the following datasets:

-

GRO-cap from ref. 83: GEO series accession number GSM1480321;

-

NetCage from ref. 85: GEO series accession number GSM3318243; and

-

Stripe-Seq from ref. 86: GEO Series accession number GSM4231304.

We obtained the raw files (fastq files) and used the FASTX Toolkit (v.0.0.14) with default parameters to trim 20 nucleotides from the end of each read. Subsequently, we used Bowtie2 (v.2.5.1) with default settings to align the reads against human rDNA (U13369.1). Reads that did not align to the rDNA were then mapped to the hg19 reference genome. We generated bigwig files using bamCoverage (v.3.5.2), setting a minimum mapping quality of 30, an offset of 1 and a bin size of 1. These bigwig files were then overlaid with our set of 30,607 TSSs. Finally, we conducted principal component analysis and used the first component as a combined measure of endogenous promoter activity, which explains 94.19% of the variance.

Measured differential promoter activity analysis

To access the differential promoter analysis on the measured data for the different conditions, we first applied a LOESS correction on the promoter activity values, then for we performed a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to evaluate the condition effects on promoter activity. Raw P values were adjusted to FDR. For the promoters with adjusted P values lower than 0.05, we consider as upregulated the promoters with log2[fold change] > 0.5 and downregulated those with log2[fold change] < −0.5.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.