Within germinal centres (GCs), B cells cycle between two zones: the dark zone (DZ) and the light zone (LZ)3,4,5. In the LZ, B cells compete for limited T follicular helper (TFH) cell help, which selects B cells based on antibody affinity for DZ re-entry. The magnitude of TFH cell help determines the level of c-Myc, which regulates both the speed and number of B cell divisions made in the DZ6,7, wherein B cells also undergo somatic hypermutation (SHM) to diversify their antibody genes3,8,9. Since nuclear membrane breakdown during mitosis is essential for DNA mutagenesis, SHM and cell division are closely linked10,11,12. Current understanding suggests that SHM continues at a constant rate per division, so that the highest-affinity B cells, which divide more often, also accumulate more mutations than their lower affinity counterparts13. However, because SHM is random, with most mutations decreasing affinity rather than enhancing it3,8,9,14, B cells dividing the most might disadvantage their progeny by acquiring more mutations. We propose and experimentally test a model in which the survival of high-affinity B cell lineages is enhanced by modulating the rate of SHM per division, allowing B cells with the highest-affinity antibodies to undergo mutation-free proliferative bursts15,16.

Despite the relatively low probability that any one mutation enhances affinity, GC responses can produce 100-fold increases in serum antibody affinity within a short period of time17. This phenomenon led us to investigate how cycles of mutation and selection might be optimized in the GC15. Herein, we sought to determine whether affinity maturation is inherently wasteful with diminishing returns for higher-affinity cells, or whether it includes mechanisms to protect these cells from accumulating affinity-reducing mutations.

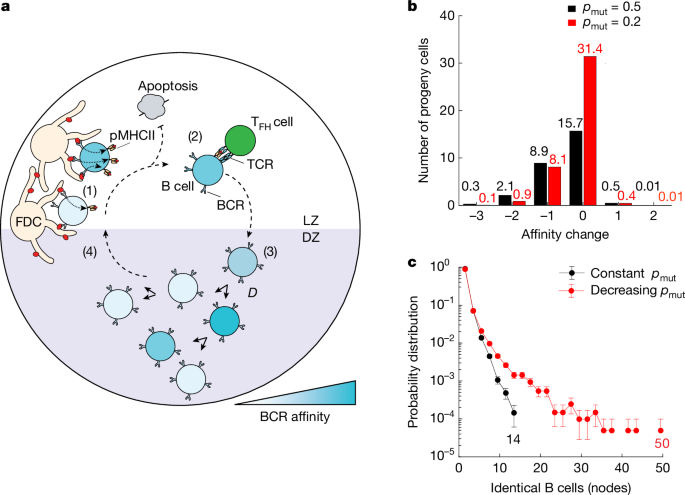

Our agent-based model makes the assumptions that competition among LZ B cells is mediated by affinity-dependent acquisition of antigens from follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) (Fig. 1a, (1)), and subsequent selection by TFH cells contingent on antigen presentation (Fig. 1a, (2)). Selected LZ B cells then migrate to the DZ and undergo a programmed number of divisions (D), which is proportional to the magnitude of TFH cell help received (Fig. 1a, (3)). Each division is accompanied by SHM with a probability of mutation (pmut ≈ 0.5)18, where mutations can be silent (psil = 0.5), lethal (plet = 0.3) (such as those that cause loss of B cell receptor (BCR) expression), affinity deleterious (pdel = 0.19) or affinity enhancing (penh = 0.01) on the basis of previously determined experimental and computational probabilities19,20,21. Following division, DZ B cells migrate back to the LZ for further rounds of affinity-based selection and then the cycle starts over (Fig. 1a, (4))6,22,23. A detailed description of the model and the parameters used in simulations can be found in Methods and in Supplementary Table 1.

a, Diagrammatic representation of key processes involved in GC reactions captured by the agent-based model (Supplementary Table 1; Methods). TCR, T cell receptor; pMHCII, peptide major histocompatibility complex II. b, Comparison of the effect of different mutation rates on B cell progeny affinities. Graph shows the number of progeny cells versus the net change in affinity produced after six consecutive divisions in the DZ, assuming a constant (pmut = 0.5 (black)) or a lower (pmut = 0.2 (red)) mutation rate. The net change in affinity is determined by calculating the difference between the number of beneficial mutations and the number of deleterious mutations. Among the 64 possible progeny cells, 25% of B cells exhibit equal or improved affinity in the constant mutation rate scenario, compared with 50% in the decreasing mutation rate scenario. c, Probability distribution of B cell node sizes in the GC for two scenarios: constant pmut = 0.5 (black) and decreasing pmut (red).

Due to the relative paucity of beneficial mutations, generation of high-affinity B cells is a rate-limiting step in affinity maturation. Clonal dominance arises in GCs by strong expansion of high-affinity somatic variants from within a clonal family, generating diversified progeny and/or small collections of identical cells that collectively augment affinity maturation16. Despite being observed in various settings16,24,25,26,27, how identical somatic variants are generated or their overall contribution to affinity maturation has not been elucidated. To understand the behaviour of high-affinity B cells and their progeny, we simulated a clonal burst in the case where the mutation probability per division pmut is a fixed value (constant pmut = 0.5) regardless of the prescribed division (D) in the DZ (Fig. 1b). Specifically, we looked at the change in affinity among the progeny of GC B cells undergoing a maximum of six consecutive cell divisions in the DZ (Fig. 1b). In this constant −pmut simulation, progeny of a DZ B cell dividing six times experienced generational degradation of affinity by the accumulation of deleterious mutations19. This, and the added probability of acquiring lethal mutations, predicted that, out of a possible 64 progeny, six divisions produced on average only 27 cells, and that more than 40% of these exhibited lower affinities than their parent. We concluded that clonal expansion at a constant rate of SHM would generate many unfit progeny and would not obviously augment affinity maturation.

To address the problem of ‘backsliding’ or affinity degradation, we explored a scenario where the probability of mutation per division, pmut, is dependent on the magnitude of TFH cell help received in the LZ. Specifically, we considered the case where the mutation probability (pmut) for B cells signalled to divide (D) consecutive times in the DZ, pmut(D), decreases linearly from pmut(D = 1) = 0.6 to pmut(D = 6) = 0.2, which would correspond to a threefold decrease in mutations per division for the progeny of high-affinity B cells. Decreasing pmut for DZ B cells dividing six times resulted in an increased average of 41 progeny cells, with now only 22% of these having lower affinity than their parent (Fig. 1b). Therefore, an affinity-dependent pmut can theoretically facilitate the preferential establishment of high-affinity B cells in the GC, without extensive generational ‘backsliding’ in affinity.

To examine whether affinity-dependent rates of mutation facilitate establishment of expanded high-affinity B cell somatic variants, we employed our agent-based model to study the size of identical B cell clones within the GC. Throughout the simulations, we tracked the mutation history of each B cell, allowing us to identify genetically identical B cells, or nodes (Fig. 1c). We found that, with a constant pmut (Fig. 1c, black), groups of identical B cells did not exceed 15 identical members. In contrast, decreasing pmut with respect to TFH cell help (Fig. 1c, red) produced remarkably larger populations of identical B cells, displaying a long-tailed distribution. Thus, a model in which T cell help modulates mutation rates favours the emergence of large groups of genetically identical high-affinity B cells (nodes).

To experimentally test whether mutation rates are variable, and dependent on both affinity and division rates, we tracked GC B cell division in mice that express mCherry labelled Histone-2b (H2b-mCherry) under the control of a doxycycline (DOX)-sensitive promoter23,28. Lymphocytes from these mice (H2b-mCherry mice) constitutively express the mCherry indicator. Administration of DOX turns off the reporter gene and, upon dividing, cells dilute the indicator in proportion to the number of divisions made, whereas quiescent cells retain the indicator22,23,28 (Extended Data Fig. 1a–c).

To track GC B cell division in vivo, we immunized H2b-mCherry mice with 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl conjugated to ovalbumin (NP-OVA), administered DOX on day 12.5 and assayed mCherry indicator dilution (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). At 36 h after DOX administration on day 14, 17% of GC B cells were mCherryhigh and 21% mCherrylow, respectively, representing GC B cells that had divided on average one or fewer times or at least six times (Extended Data Figs. 1c and 2b).

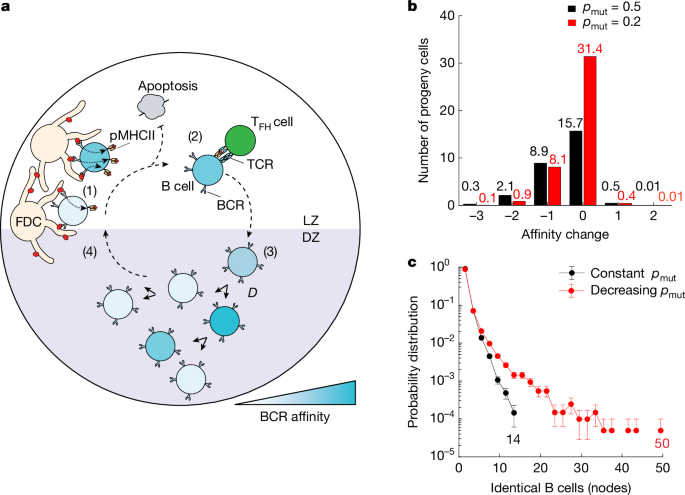

To characterize the relationship between SHM and cell division, we purified mCherryhigh and mCherrylow GC B cells from the popliteal lymph nodes of NP-OVA-immunized DOX-treated mice and performed single-cell mRNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) using the 10X Chromium platform. To profile clonality, we used paired immunoglobulin heavy (IgH)- and light (IgL)-chain sequences that resolved families of related cells (clones) derived from common ancestors. Consistent with their higher levels of cell division, mCherrylow populations were significantly more clonal than the corresponding mCherryhigh populations (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2c). As surrogates for affinity, we compared the frequency of anti-NP affinity-enhancing mutations (W33L, K59R and Y99G in cells using IgHV1-72 (ref. 29)) and measured NP-fluorophore binding by flow cytometry. On average, GC B cells that had undergone more divisions (mCherrylow) were significantly enriched for cells with affinity-enhancing mutations and measurable NP-fluorophore binding compared with those that divided less (mCherryhigh) (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). Therefore, cells that divided the greatest number of times showed significantly higher affinity for antigen compared with cells that divided less.

a, Pie charts depicting clonal distribution of antibody sequences obtained from mCherryhigh or mCherrylow NP-OVA elicited GC B cells from four of n = 7 mice analysed (M1–4). Numbers inside charts indicate the total sequences analysed per compartment. Coloured slice sizes are proportional to the number of clonally related sequences; white slices represent singles (sequences isolated only once). b, Representative genotype-collapsed phylogenetic trees containing nodes with more than 15 identical members. UCA (inferred) sequences appear at the root of the tree, connected (dashed line) to observed sequences (nodes) by branching. Sub-branching (solid line) reflects mutational distance between observed sequences (nodes). Scale bars represent mutational distance in nucleotides (per tree). Circle centres display the number of identical sequences in a node. Pink outlined nodes indicate sequences carrying any one of the affinity-enhancing mutations (W33L, K59R, Y99G). mCherryhigh and mCherrylow nodes are filled red-orange and white, respectively. c, Bar graph showing the percentage of nodes containing 1 (blue), 2–15 (purple) or more than 15 (green) identical sequences among expanded clones for each of the 7 mice analysed. d, Bar graph showing percentage of total sequences that contributed to nodes containing 1 (blue), 2–15 (purple) or more than 15 (green) when analysis is extended to all cells (clones and singles). e, Graph displays size distributions of nodes with two or more identical sequences (derived from cells expressing IgHV1-72, paired with a lambda (λ) light chain) for cells with any (pink) or without (black) affinity-enhancing mutations (W33L, K59R, Y99G). *, Welch’s t-test (two-sided) shows significance (P < 0.05).

Despite being derived from the same unmutated common ancestor (UCA), expanded clones are heterogeneous, composed of a collection of diversified somatic variants (nodes) that have accumulated additional point mutations due to SHM. Genotype-collapsed phylogenetic trees were produced to visualize the contribution of individual somatic variants to each of the expanded clones (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 2f)21,30. UCAs are shown at the roots of the trees and are connected to variants through branching, as indicated by dotted lines. Sub-branching (solid lines) illustrates mutational distance between variants. Division, as measured by mCherry dilution and affinity-enhancing mutations (pink outline), were also mapped onto the tree to annotate cell division status and relative affinity (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 2f).

Our modelling predicts that a constant mutation rate of around 1 × 10−3 per base pair per cell division1, equivalent to approximately 50% chance of mutation per division pmut = 0.5, should produce branched trees containing limited small collections of identical sequences (nodes) of 15 or fewer cells (Fig. 1c, black). Alternatively, the decreasing pmut model, with otherwise identical simulation parameters, predicted trees with nodes that extended up to 50 cells (Fig. 1c, red). Analysis of the experimental data revealed trees with nodes comprised of 2–15 members as well as trees with much larger nodes that contained 15–125 identical members (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 2f). These grossly expanded nodes (more than 15) could not be accounted for by the constant pmut model but were more consistent with the decreasing pmut model.

Among the expanded clones, the fraction of nodes containing either 1, 2–15 or more than 15 genetically identical sequences were 50%, 47% and 3%, respectively (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 2). Thus, only a small fraction of all nodes have more than 15 identical sequences. However, when all sequences were considered independently, on average 18% of all GC B cells were found in nodes that carry more than 15 identical sequences (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 3). Therefore, mutation-free clonal bursts produce a large assortment of identical progeny that contribute to the GC reaction.

To examine how affinity might impact node formation and size, we compared nodes from IgHV1-72 (heavy chain that is associated with optimal NP-binding activity31) GC B cells that had or had not yet acquired one of the affinity-enhancing mutations (W33L, K59R, Y99G). Larger nodes were enriched among GC B cells carrying affinity-enhancing mutations (Fig. 2e). In conclusion, the experimental data are in keeping with the theoretical model suggesting that the GC reaction is optimized by mutation-free proliferative bursts of cells expressing high-affinity antibodies.

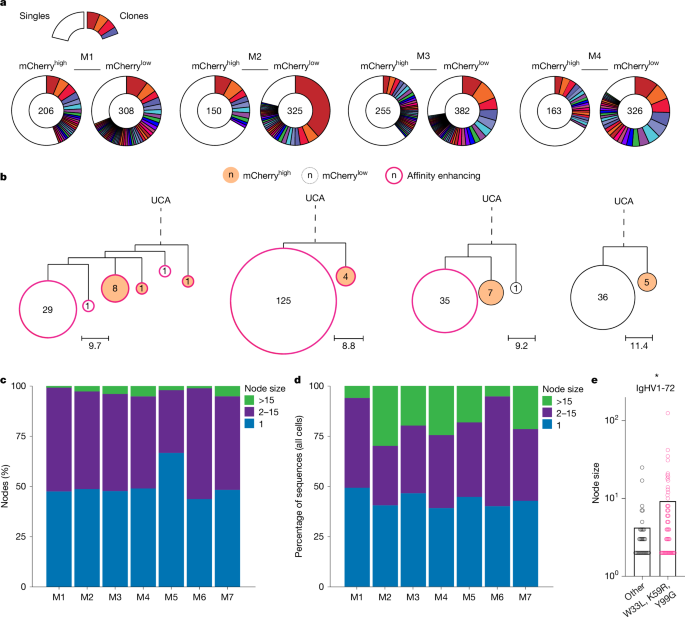

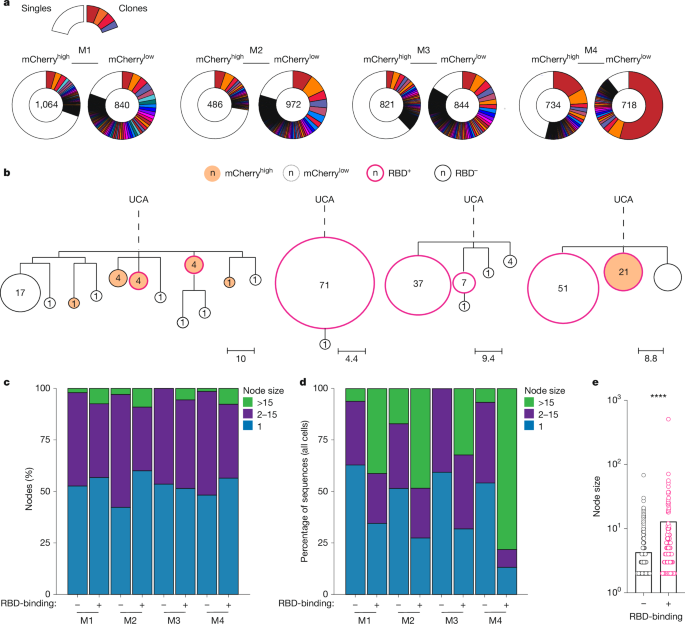

Immune responses to simple haptens like NP might differ from more complex protein antigens. To determine the contribution of mutation-free clonal bursts to immunization with a vaccine antigen, we performed single-cell analysis of GC B cells obtained from draining lymph nodes of H2b-mCherry mice immunized with the receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 in adjuvant (Extended Data Fig. 3a). GC B cells obtained 14 days after vaccination, and 36 h after DOX exposure were barcoded according to RBD-binding and mCherry expression, allowing paired analysis of sequence identity, division status and RBD-binding as a surrogate for affinity (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Genotype-collapsed phylogenetic trees were produced using paired IgH- and IgL-chain sequences from expanded clones (Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 3c). RBD-binders (RBD+, pink outline), and RBD-non-binders (RBD−, black outline) were annotated along with cells’ mCherry expression (filled) (Fig. 3b). Similar to NP-OVA immunization, we observed large nodes containing identical sequences, indicating that extensive mutation-free clonal bursts occurred during SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (Fig. 3a–c). When only expanded clones were considered, the fraction of nodes with 1, 2–15 and more than 15 identical sequences represented 51%, 46% and 3% of all the nodes, respectively (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Table 4). Since large nodes contribute disproportionately, when all cells were considered independently, on average 24% of all GC B cells were derived from nodes that carry more than 15 identical sequences (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 5). Notably, the fraction of nodes containing more than 15 identical sequences was always greater among RBD+ as compared to RBD− cells (Fig. 3d,e (P < 0.0001) and Supplementary Table 5).

a, Pie charts depicting clonal distribution of antibody sequences obtained from mCherryhigh or mCherrylow RBD-elicited GC B cells from n = 4 of the mice analysed. Numbers inside charts indicate the total sequences analysed per compartment. Coloured slice sizes are proportional to the number of clonally related sequences; white slices represent singles (sequences isolated only once). b, Representative genotype-collapsed phylogenetic trees as in Fig. 2b. Sequences obtained from RBD+ and RBD− sorted cells are outlined in pink and black, respectively. mCherryhigh and mCherrylow nodes are filled red-orange and white, respectively. c, Bar graph showing the percentage of nodes containing 1 (blue), 2–15 (purple) or more than 15 (green) identical sequences in the RBD+ and RBD− compartments among expanded clones for each of the four mice analysed. d, Bar graph showing percentage of total sequences that contributed to nodes containing 1 (blue), 2–15 (purple) or more than 15 (green) identical sequences among RBD+ and RBD− fractions when all cells were considered (clones and singles). e, Graph showing size distribution of nodes containing two or more identical sequences among RBD+ (pink) and RBD− (black) cells. ****P < 0.0001, by both unpaired Student’s t-test, (two-sided) and Welch’s t-test (two-sided, log-transformed).

To verify this enrichment and confirm that RBD-binding reliably reports on relative affinity, we produced fragment antigen-binding region (Fabs) templated from cells belonging to RBD+ and RBD− nodes from expanded clones and measured affinity constants (Kd) by bio-layer interferometry (Extended Data Fig. 4a–d). With only two exceptions, RBD+ nodes all produced high-affinity antibodies and RBD− nodes showed little or no measurable affinity. When all Kd values were considered, antibodies from RBD+ nodes were significantly higher in affinity (lower Kds) than those from RBD− nodes (Extended Data Fig. 4d; P < 0.0001). Thus, protein and hapten immunization are similar with respect to production of expanded nodes of high-affinity cells with identical sequences.

To determine whether these effects were adjuvant specific, we profiled GC B cells responding to SARS-CoV-2-mRNA vaccination (Extended Data Fig. 5a). GC B cells were obtained 14 days after mRNA vaccination, and 36 h after DOX exposure and isolated according to mCherry status. Single-cell sequencing was performed to resolve paired IgH- and IgL-chain sequences. Genotype-collapsed phylogenetic trees obtained from the expanded clones confirmed the contribution of large nodes to affinity maturation (Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). Thus, expanded cells with identical sequences arise in GCs elicited by different immunogens and adjuvants.

Profiling mCherryhigh and mCherrylow B cells is useful to compare cells that had divided one or fewer times versus at least six times following DOX exposure. However, as many GC cells were mCherryintermediate, many GC B cells were excluded from this analysis. To assess the contribution of mutation-free clonal bursts to total GC responses, we performed single-cell analysis of all GC B cells responding to RBD vaccination (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). Consistent with the data obtained by mCherry fractionation, we observed large nodes containing identical sequences that contributed significantly to affinity maturation during SARS-CoV-2-RBD vaccination (Extended Data Fig. 6d–g). As expected, the grossly expanded nodes of B cells with more than 15 identical sequences also contributed disproportionately to the overall number of B cells and were highly enriched within high-affinity (RBD+) clones (Extended Data Fig. 6e–g). Thus, mutation-free clonal expansion contributes to affinity maturation in GC reactions across a range of immunological challenges.

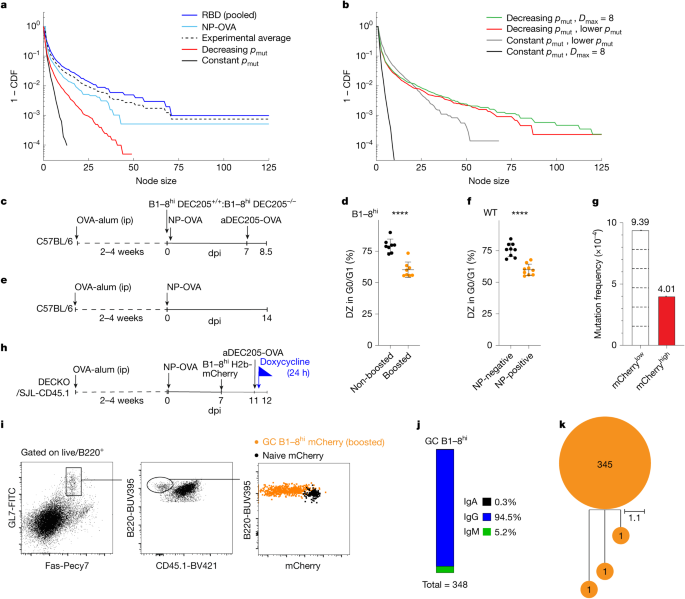

To determine how the experimental data compared with the theoretical predictions we plotted the experimental cumulative distribution function (CDF) of node sizes alongside the simulations (Fig. 4a). Notably, the experimental results were closer to the node size distribution predicted by the decreasing pmut model than the constant pmut model. However, despite the qualitative similarities, the experimental cohorts displayed even longer tails not seen in the decreasing pmut model. We reasoned that this discrepancy might be due to overly conservative assumptions about the maximum number of cell divisions per DZ cycle (six), which was inconsistent with the size of some of the experimentally observed nodes, or the choice of mutation probability for highly dividing B cells. Modestly changing the maximum number of cell divisions from six to eight produced a model that displayed a longer-tailed node size distribution and largely resolved the differences with respect to the experimental results (Fig. 4b, green). This change is more consistent with the experimental data that contained nodes with more than 64 cells in which more than six divisions have probably occurred. Alternatively, preserving the maximum number of divisions at six (D = 6), but decreasing the mutation rate (pmut) linearly from 0.6 to 0.1 in the decreasing −pmut model also yielded a node size distribution consistent with experiments (Fig. 4b, red). In contrast, significantly lowering pmut or, alternatively, extending the number of cell divisions in the constant pmut model from six to eight did not yield a distribution of node sizes consistent with the experimental data (Fig. 4b, black and grey).

a, Graph plotting CDF of node sizes from model simulations and experimental data. For the decreasing pmut model (red), a linearly decreasing per division mutation probability as a function of number of divisions D from pmut(D = 1) = 0.6 to pmut(D = 6) = 0.2 was used, yielding \({\bar{p}}_{{\rm{mut}}}=0.48\), where \({\bar{p}}_{{\rm{mut}}}\) is the average per division mutation probability experienced. Averages over ten simulation runs are plotted. b, Graph comparing simulated node size CDF for alternate choices in the maximum number of divisions and mutation probability. Decreasing pmut models where the maximum number of divisions is eight, Dmax = 8, with linearly decreasing mutation probability from pmut(D = 1) = 0.6 to pmut(D = 8) = 0.12 yielding \({\bar{p}}_{{\rm{mut}}}=0.44\) (green), and decreasing pmut model with Dmax = 6 but with linearly decreasing mutation probability from pmut(D = 1) = 0.6 to pmut(D = 6) = 0.1 yielding \({\bar{p}}_{{\rm{mut}}}=0.45\) (red) are shown. Constant pmut models with lower pmut = 0.2 (grey) and pmut = 0.5 but with Dmax = 8 (black) are shown. Average over five simulation runs plotted. c, Schematic representation of the experiment used in d. ip, intraperitoneal injection. d, Graph showing percentages of non-boosted B1–8hi DEC205−/− (black) or boosted DZ B1–8hi DEC205+/+ (orange) B cells in G0/G1 among n = 8 mice assayed. ****Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing non-boosted and boosted shows significance (P > 0.0001). e, Schematic representation of the experiment shown in f. f, Graph showing percentage of NP non-binding (negative-black) or NP-binding (positive-orange) DZ B cells in G0/G1 among n = 9 mice assayed. ****Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing NP-negative and NP-positive fractions shows significance (P > 0.0001). g, Re-analysis of SHM within JH4 intron of mCherrylow or mCherryhigh GC B cells23. Dashed lines indicate divisions. Experiments were performed at least twice, error bars plot mean and s.d. h, Schematic for i–k. i, Representative flow cytometric plots profiling mCherry dilution from B1–8hi H2b-mCherry GC (orange) or naive B cells (black) 24 h after boost; 348 GC B1–8hi H2b-mCherry DEC-205+/+ VH regions sequences were retrieved across the six mice assayed. j, Bar chart interrogating isotype switching. k, Single tree visualizing SHM in VH regions of the 348 sequences. Unmutated sequences appear at the root, and diversified progeny appear as sub-branching. dpi, days post immunization.

Finally, we considered whether stochasticity in the constant pmut model could account for the large nodes observed in experimental data. To this end, we simulated the case with stochastic pmut (Extended Data Fig. 7a), and the case where the number of divisions corresponding to a constant level of T cell help was stochastic (Extended Data Fig. 7b). We found that neither scenario could account for the long-tail behaviour of node sizes observed in experiments. Thus, both the theory and experimental data are consistent with the idea that the per division rate of SHM is regulated and decreases with increasing T cell help.

SHM is mediated by the enzyme activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)2,14,32,33,34,35. AID has relatively poor catalytic activity and even small changes to AID expression result in changes in the rate of SHM36. To determine whether variable mutation rates in GC B cells were mediated by altered AID expression in expanded nodes, we profiled its expression in NP-OVA and RBD-elicited GC B cells contributing to nodes of sizes 1, 2–15 or more than 15 (Extended Data Fig. 8a–c). Despite the absence of SHM in grossly expanded nodes, there were no significant decrease in Aicda transcript levels in the larger node classes. Thus, differential Aicda expression levels are not likely to be responsible for the absence of mutation in large nodes.

AID introduces C>U mutations at preferential nucleotide sequence hotspots (WRC, W = A/T, R = A/G, underline indicates residue targeted for mutation)37,38. To determine whether absence of SHM in expanded nodes was due to previous loss of these motifs, we profiled AID hotspots between cells contributing to nodes of sizes 1, 2–15 or more than 15. Hotspot motifs were equally intact in cells belonging to all three classes of nodes (average 92%, 93% and 94%, respectively; Extended Data Fig. 8d–f). Thus, target motif decay does not account for differences in SHM between nodes. Finally, we compared the level of cell death among mCherry compartments and found no significant differences (Extended Data Fig. 8g,h).

SHM is cell cycle dependent and limited to the G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle, when AID is in spatial contact with genomic DNA10,11,12,22,23. High-affinity B cells receiving strong T cell help transit through the S phase of the cell cycle faster than their low-affinity counterparts, but the consequences on the G0/G1 phase of the cycle and on SHM have not been examined22. To determine how regulation of the cell cycle might contribute to variable, per division mutation rates, we initially used anti-DEC205 chimeric antibodies to deliver strong selection signals to GC B cells23,39. Congenic DEC205+/+ B1–8hi B cells were adoptively transferred into OVA primed mice that were subsequently immunized with NP-OVA and later boosted with anti-DEC205-OVA chimeric antibodies or left non-boosted (Fig. 4c)39,40. Cell cycle analysis by DNA content revealed that B1–8hi B cells that received strong selection signals (boosted, orange) and experienced a greater number of divisions were significantly less likely to be in G0/G1 than controls (non-boosted, black) (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 9a).

To determine whether shorter time spent in G0/G1 was a feature of high- versus low-affinity B cells participating in polyclonal immune responses, we immunized OVA primed mice with NP-OVA and measured the cell cycle distribution of DZ cells that bound to NP-fluorescent bait by flow cytometry as a surrogate for affinity (Fig. 4e,f and Extended Data Fig. 9b; P < 0.001). The proportion of DZ NP-fluorophore binding cells in G0/G1 was significantly lower than non-binder DZ counterparts (Fig. 4f, P < 0.001). These results imply that high-affinity B cells cycle through the G0/G1 phase significantly faster than low-affinity B cells, shortening the time for AID mutator activity and thereby decreasing mutation probability per division, thus leading to the long-tailed behaviour of node sizes predicted by the decreasing pmut model and as observed in our experiments. Notably, altering the speed of the cell cycle without changing the per division mutation probability in our simulations does not result in changes to the node size distribution (Extended Data Fig. 10).

To confirm that GC B cells that divide more also mutate less per cell division we re-examined mutation rates in the IgH JH4 intron in DZ B cells from H2b-mCherry mice immunized with NP-OVA (Fig. 4g)23. The IgH JH4 intron was selected because mutations in this region are not subject to selection. We observed that mCherrylow cells that had divided at least six times were only approximately 2- to 2.5-fold more mutated (not the expected sixfold) than their mCherryhigh counterparts that had divided once or less, representing a roughly two- to threefold lower mutation rate per division in cells that undergo several rounds of division in the DZ (Fig. 4g)23.

To determine how the altered cell cycle might impact SHM, we delivered strong selection signals to GC B cells using anti-DEC205-OVA (ref. 22). Congenic DEC205+/+ H2b-mCherry B1–8hi B cells that express high-affinity receptors for NP were adoptively transferred into polyclonal host mice that had been immunized with NP-OVA 7 days previously (Fig. 4h). Approximately 3.5–4 days after the transfer, enough time for B1–8hi B cells to become activated and enter the GC but not enough for the accumulation of SHM41, we administered DOX and anti-DEC205-OVA to track cell division and deliver a strong selection signal, respectively (Fig. 4i)23,39. Although asynchronous, most DEC205+/+ B1–8hi B cells underwent at least two divisions within the 24-h observation period, as compared with naive H2b-mCherry counterparts, as captured by respective mCherry dilution or retention (Fig. 4i). Despite division and class switch recombination, which would have occurred after activation and before GC entry42, B1–8hi IgVH sequence analysis revealed only eight base pairs were mutated in a total 125,628 bases sequenced, generating only three mutated cells out of total of 348 cells (Fig. 4j,k and Extended Data Fig. 9c). Thus, the observed rate is significantly less than the accepted rate of one mutation per 103 bp per division.

Together these data are consistent with the idea that strong selection signals decrease the relative time DZ cells spend in G0/G1, thereby reducing their exposure to AID and lowering their per division mutation rates.