The Pacific Ocean’s seabed is rich in critical metals such as cobalt and nickel. Yet deep-sea mining of these materials, which are used in many technologies, threatens the region. If mining goes ahead, irreversible environmental harm, risks to ocean health and climate stability, as well as uncertain economic gains and geopolitical tensions, would destabilize this peaceful ‘ocean continent’ — known as the Blue Pacific.

As leaders of two Pacific island nations, Palau and Mā’ohi Nui–French Polynesia, we bear a profound responsibility to help protect this ocean. Our countries have combined national waters, known as exclusive economic zones (EEZs), spanning more than 5.3 million square kilometres, or 4% of the world’s total EEZ area. Beyond being a resource and crucial part of the planet, the ocean is deeply interwoven with the spiritual identity and cultural heritage of our communities. It is the cradle of life, deserving of respect and protection. This sacred connection, and more, compels us as collective stewards to oppose the intensifying global interest in ocean mining.

Why we should protect the high seas from all extraction, forever

International consortia and state-backed enterprises are exploring deposits of polymetallic nodules, cobalt-rich crusts and sea-floor sulfides. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Kingston, Jamaica, has already issued more than 30 exploration contracts to 22 bodies, with almost two-thirds (61%) of these contracts linked to high-income countries. For Pacific nations hosting some of Earth’s richest metal deposits, valued in the trillions of dollars, the issue is urgent. Although several Pacific states are considering deep-sea mining in their EEZs, hoping for economic benefits, many Pacific communities remain strongly opposed.

Here, we argue that ocean health and climate protection must outweigh risky short-term extraction. Pacific deep-sea mining must not advance without clear evidence of no irreversible harm1. Economic volatility, limited local benefits, devastating ecological impacts and climate risks represent unacceptable threats. Instead, we urge Pacific nations and the international scientific community to support sustainable ocean economies, innovation, cultural integrity and responsible global stewardship for future generations.

Questionable economic benefits

Proponents often portray deep-sea mining as an engine for economic development in the Pacific, promising revenues, jobs and infrastructure. But that won’t necessarily be the case. Economic considerations alone provide sufficient grounds for extreme caution.

The metals mined in deep seas — particularly cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese — are often subject to drastic and unpredictable price swings. And increased metal supply from deep-sea mining could depress global prices of these minerals, as happened in the 1970s2. Future demand also remains uncertain owing to rapid advancements in recycling and alternative materials.

I’ve witnessed the wonders of the deep sea. Mining could destroy them

Deep-sea mining’s capital-intensive nature requires small, specialized crews, limiting local employment opportunities because of the scarcity of relevant expertise in Pacific island nations. Training programmes, such as those proposed by the Cook Islands, might prove less effective at job creation than would investments in other sectors, such as coastal tourism or fisheries, which rely more heavily on local skills and employ more people per dollar invested.

Deep-sea mining might yield minimal fiscal returns for Pacific nations. In international waters (the high seas), mining royalties must be shared among all ISA member states, drastically reducing any single country’s benefit. In national jurisdictions, anticipated taxes and royalties are likely to be modest, and are often weakened by inadequate fiscal regimes and investor-friendly agreements — some of which even waive corporate income taxes entirely for operators3.

Hurdles include adequate governance and sufficient institutional capacity, as highlighted in the 2024 Columbia University Capstone Report that assessed deep-sea mining around Mā’ohi Nui4. And governments would face costs as well as risks. Oversight and environmental monitoring require substantial public expenditure on regulatory capacity, scientific assessments and enforcement5. In the case of an environmental disaster or the mining company going bankrupt, the country might have to shoulder liabilities or clean-up costs.

For example, in 2019, Papua New Guinea’s government lost its entire investment of US$120 million to secure a 15% stake in a deep-sea mining project, Solwara 1, when the Canadian company behind it, Nautilus Minerals, went bankrupt. The resulting debt amounted to around 10% of the country’s 2019 budget deficit.

Nature collection: The ocean in humanity’s future

Economic risks would persist even if deep-sea mining took off. For instance, a sudden increase in resource production might prompt an appreciation in the value of the local currency and domestic inflation, which would undermine other export industries. A mining boom would draw labour, capital, attention and investments away from other industries that are crucial to many Pacific economies, such as tourism, fisheries and agriculture.

Similarly to oil-production operations that are dependent on volatile prices, deep-sea mining could quickly become economically unfeasible amid falling prices or rising environmental costs. Expanded mining operations could trigger intensified international competition, leading to a damaging race to the bottom. Declining global commodity prices would destabilize economies that are overly reliant on mining revenues. Governments might feel forced to deregulate environmental and labour standards to remain economically viable.

Irreversible environmental harms

The deep sea, a vast wilderness of unique biodiversity, performs crucial planetary functions that are not fully understood. The case of the island of Nauru highlights the dangers of resource depletion and mismanagement: decades of intensive phosphate mining in its interior brought temporary wealth, but ultimately led to environmental degradation, economic hardship and public-health crises that affect Nauruans to this day.

The impacts of deep-sea mining extend far beyond the seabed, spreading through the water column and currents, potentially affecting fisheries, marine mammals and neighbouring jurisdictions. Whether extracting polymetallic nodules from sea-floor sediments or mining hydrothermal vents, operations risk extensive and irreversible habitat destruction.

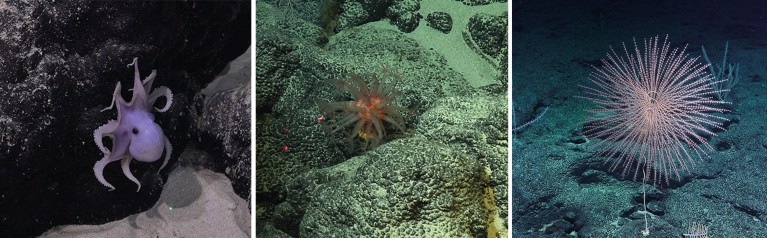

A rare species of Pacific octopus (left); a mushroom coral amid cobalt-rich deposits (centre) and an Iridogorgia spiral coral.Credit: Left and right, ROV SuBastian/Schmidt Ocean Institute; centre, Christopher Kelley/NOAA

Hydrothermal vent fields in regions such as the Manus Basin (off Papua New Guinea) and the Lau Basin (near Tonga) host unique, endemic species, including specialized shrimp, snails and tubeworms. Although commercial mining has not yet begun in these regions, alteration of these isolated habitats will inevitably lead to biodiversity loss. This could disrupt marine food webs and ecosystem functions that are crucial to fisheries and Pacific communities. Studies show that even experimental disturbances result in incomplete ecological recovery after decades6.

Sediment plumes from mining operations are a big concern, because they can drift across hundreds of kilometres for decades, smothering organisms and degrading water quality7. These plumes can cross national jurisdictions and diminish catch rates or contaminate seafood, potentially affecting fishing grounds that are crucial for coastal communities and threatening food security. Pelagic ecosystems, which are essential for migratory species such as tuna and whales, plankton and those in the broader marine food web, would also be at risk8.

Noise and artificial light from mining machinery can disorient marine life and disrupt crucial processes, such as bioluminescence and vertical migrations, that are essential for nutrient cycling. These disturbances threaten commercially valuable fish populations, particularly tuna, through impaired respiration, bioaccumulation of metals and disruptions to reproduction and to feeding (including hunting difficulties caused by plumes)9.

Geopolitical risks

The widespread impacts of deep-sea mining will create legal and geopolitical challenges. Neither the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea nor the ISA has a robust international mechanism by which to assign liability effectively and provide compensation for damage arising from mining activities10.

To save the high seas, plan for climate change

If pollution from high-seas mining affects fisheries or reefs in another nation’s territory, there is no clear recourse. A case in point is the 2009 Montara oil spill. Originating from a rig in Australian waters, the spill reached Indonesian waters, leading to claims of damage to fisheries and coastal livelihoods there. This underscores the urgent need for pre-emptive legal clarity before deep-sea mining operations commence.

Large-scale mining also introduces security and monitoring challenges across vast maritime areas. Addressing these pressures demands unwavering regional unity and a cautious approach that prioritizes long-term Pacific well-being. Pacific nations have strengthened their collaboration through the Blue Pacific approach, which has reimagined our maritime territories as an interconnected ‘ocean continent’ to foster collective identity and unified action.

Practically, this translates into stronger joint advocacy in global forums on climate action, fisheries management and marine conservation. It also enables shared strategies for resource management and maritime security, aiding cooperation while respecting diverse national approaches in this common regional vision.

Climate regulation disruption

An alarming, poorly understood risk is the potential of deep-sea mining to disrupt the ocean’s role in climate regulation as the largest carbon sink. Disturbing the sea bed can release carbon or methane that have been stored in sediments for millennia11, potentially exacerbating climate change and ocean acidification.

At experimental mining sites, more than two decades after simulated disturbance, sea-floor fauna remained depleted12, microbial communities were impaired and both groups showed a reduced capacity for carbon processing.

A coastal village in Papua New Guinea. The country lost US$120 million on a failed deep-sea mining project.Credit: Joerg Boethling/Alamy

For low-lying Pacific islands, these risks are existential. Communities are already confronting the severe realities of climate change. In Palau, for instance, rising sea levels are not an abstract threat but a present danger, forcing coastal communities to watch as their homes are inundated, crucial freshwater sources are contaminated by saltwater intrusion and ancestral burial grounds become vulnerable. Intensified storms such as Typhoon Haiyan, which brought widespread devastation to Palau, increasingly threaten homes, infrastructure such as hospitals and schools, and the safety of our people.

Furthermore, extensive coral bleaching events, driven by warming seas, decimate the reefs that are fundamental to Palauan livelihoods, leading to declining fish catches that underpin our food security and local economies. Bleaching also weakens the natural coastal defences that protect our islands. Any activity, such as deep-sea mining, that further destabilizes the climate system is therefore unacceptable11,12.