Far from being a remote, isolated continent, Antarctica is integral to Earth’s climate and life-support systems. Its vast ice sheet stores more than 90% of the planet’s surface fresh water and influences sea levels, circulation of the atmosphere and how much sunlight the planet reflects. Around Antarctica, the Southern Ocean acts as the lungs of the deep sea, accounting for roughly 40% of the global ocean’s uptake of carbon dioxide emissions generated by human activities, shaping how seawater mixes and distributes nutrients to support marine life around the globe1.

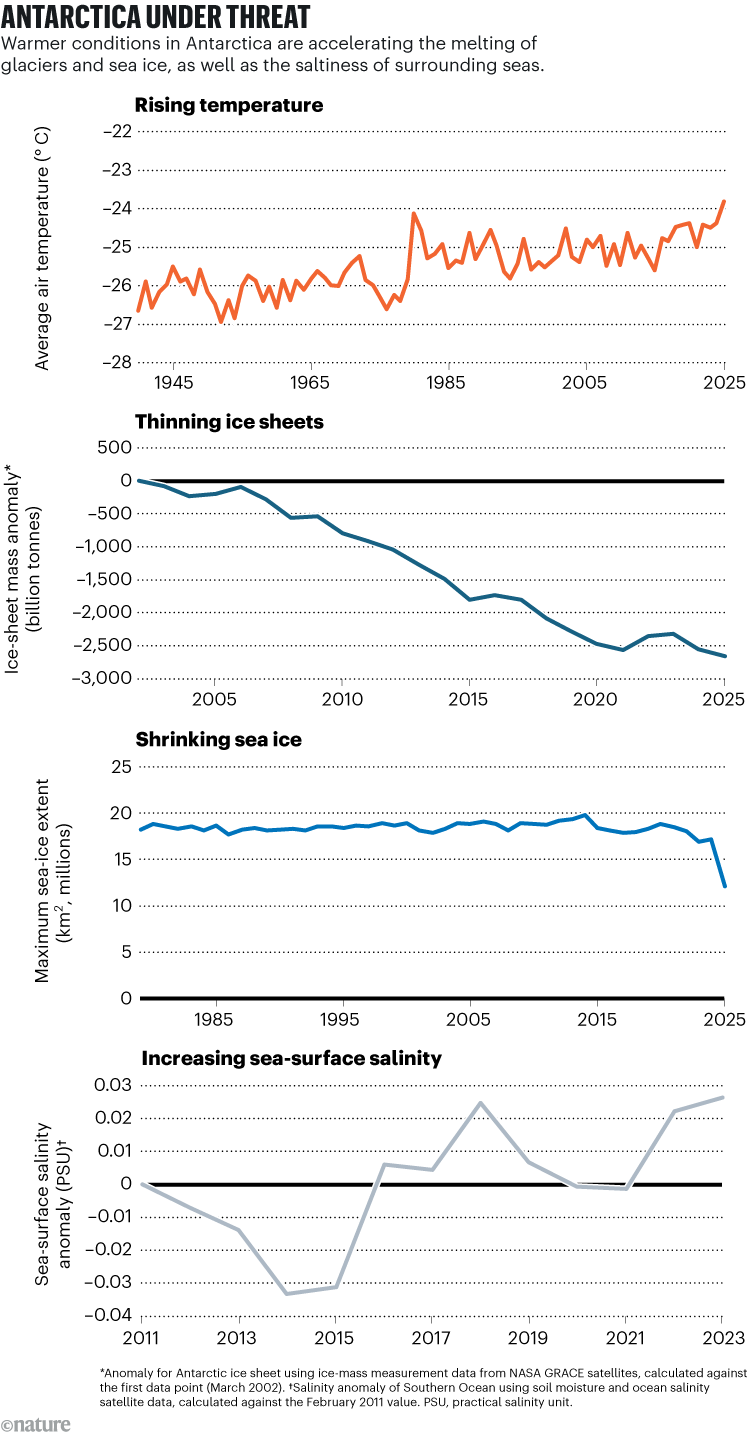

Yet, many of these stabilizing features are showing signs of degradation. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is retreating, with widespread thinning of glaciers and ice shelves. Changes there are accelerating, as damage in one area exacerbates melting and stresses in others. And now, parts of the more stable East Antarctic Ice Sheet seem to be thinning, too2. Pooling melt water on its surface would eat away at the ice further3, possibly triggering the break-up of more ice shelves4. Meanwhile, Antarctic waters seem to have entered a new regime, with record-low sea ice, greater salinity and less stratification of upper ocean layers5,6 (see ‘Antarctica under threat’).

Sources: Temp.: https://go.nature.com/3JFQNKP; Ice sheet: https://go.nature.com/4JPPG5G; Sea ice: https://go.nature.com/45GDTPW; Salinity: Ref. 5.

Runaway melting in the Antarctic will be grave for the world. Loss of ice could contribute more than 60 centimetres to sea-level rise by the end of this century and will disrupt the Southern Ocean’s freshwater balance, circulation and mixing7 — signs of which are already evident in some areas8. Less general ocean mixing means that less oxygen and fewer nutrients are transferred to the deep ocean, making it harder for marine organisms there to survive and reproduce, as well as lowering the ability of the seas to take up carbon.

Before this crucial reservoir of ice is lost, transforming the planet forever, it is essential that policymakers and others recognize Antarctica’s extraordinary economic value and seek to protect it. Environmental services, fisheries and tourism in Antarctica contribute more than US$180 billion to the global economy each year9. Yet, governments and businesses continue to undervalue these services, prioritizing political aims and short-term financial objectives (such as maximizing profit or gross domestic product) over sustaining the stability of the planet, which supports people’s lives and underpins all economies.

Strategies are needed to broaden society’s goals beyond financial gains and to account for long-term risks and benefits. Here, we set out what’s at stake and propose economic goals and governance changes to guide policy responses towards long-term planetary stability.

Continent under threat

As the ice melts and oceans change, ecological stresses are intensifying across the Antarctic. Populations of krill — key prey for penguins, whales and seals — are declining as oceans acidify10, affecting the whole region’s food web. Shrinking sea ice exacerbates these threats11. For example, if seals and penguins find it harder to obtain krill, especially at crucial times such as breeding periods, populations will be more vulnerable to more frequent and extreme disturbances, such as heatwaves or algal blooms.

On the Antarctic Peninsula and sub-Antarctic islands, warming is driving changes in vegetation and species distributions. For example, fast-spreading grasses are crowding out native vegetation, disrupting nesting habitats for seabirds and altering nutrient cycles. Thawing permafrost releases greenhouse gases and might awaken dormant microorganisms, with unpredictable consequences12.

Why we should protect the high seas from all extraction, forever

Human activities compound these pressures. Invasive species, including grasses, insects and microbes, transported by visitors and cargo, are beginning to colonize ice-free areas13. Pollution, too, is on the rise: persistent organic pollutants, hydrocarbons and microplastics have been detected across the region, including in seabirds and marine sediments14. These substances accumulate in food webs and impair reproductive and immune systems in native fauna.

All of these changes are linked and interact in ways that are often non-linear and self-reinforcing. For example, ice-sheet retreat adds fresh water to the seas, which weakens ocean circulation and accelerates warming and acidification, destabilizing marine ecosystems. Humans can increasingly reach regions that were once isolated, spreading pollution and invasive species and disturbing habitats. These cascading dynamics raise the possibility of ‘runaway’ change, in which the breach of one threshold makes others more likely, eventually overwhelming the capacity for intervention.

Lack of oversight

Meanwhile, monitoring systems in the Antarctic remain inadequate. Environmental assessments often focus on linear trends and single variables, underestimating how multiple pressures converge and reinforce each other. This limits scientists’ abilities to detect early warning signs and precludes coordinated preventive actions.

Fragile governance is also increasingly a problem. The Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) has maintained peace and scientific cooperation in the region for more than six decades. It includes the 1959 treaty and subsequent agreements on wildlife, marine conservation and environmental protection. However, its consensus-based structure and slow pace of reform are struggling under the pressures of the twenty-first century.

Rising numbers of human visitors risk disrupting nesting sites for seabirds.Credit: Ida Kubiszewski

Diplomatic stalemates about issues such as new marine protected areas and the approval of further consultative parties to the treaty are straining the system. Expanding national scientific programmes and rising commercial activities, including fishing and tourism, test the system’s resilience.

Should the ATS lose legitimacy or fail to enforce protections, it could open the door to unregulated exploitation and even geopolitical conflict. Weakening of Antarctic governance could further erode environmental stewardship and fracture international collaboration on climate and biodiversity15.

Solutions for a stable future

Preventing irreversible change in the Antarctic and Southern Ocean requires urgent, system-wide transformation — across governance, science, economics and public engagement — as well as the rapid reduction of global emissions to curb climate change.

Antarctic governance must evolve to be fit for the Anthropocene — the age of significant and lasting human impacts on the planet. The ATS requires stronger enforcement mechanisms, faster institutional responsiveness and more-efficient ratification processes. Reforms could include capping tourist numbers and re-evaluating the ‘use’ principle, which allows any tourism activity that national authorities approve, except those that are explicitly prohibited.

Does US science have a future in Antarctica? Trump cuts threaten to cancel fieldwork and more