Our analysis framework comprised nine main stages, summarized in Extended Data Fig. 1.

Preparation of consistent geotemporal climatologies, 2000–2050

Historical climate data

Climate data were obtained from the Climate Hazards Centre36 and Climate Research Unit gridded Time Series37, downscaled by Worldclim38. Data were gap-filled53, aligned to a standard 5 × 5 km reference grid and aggregated to monthly time-steps. Details of all historical climate data used in this study are provided in Supplementary Information Table 1.

CMIP6 projections

Projections of future climate under SSP 2-4.5 were obtained from the NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Projections (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6)35. These data consist of downscaled and bias-corrected daily CMIP6 multi-model ensemble outputs for historical (2000–2014) and future projection (2015–2050) eras. Data were aggregated to monthly resolution before applying the delta method54 to provide a final calibration to historical climate data described above. To account for between-model uncertainty, 14 models were processed and used for projection of ecologically driven climate impacts (Supplementary Table 2), whereas a thinned subset of three models (ACCESS-CM2, EC-Earth3-Veg-LR and MPI-ESM1-2-LR) was used for the additional analysis of disruptive climate impacts.

Modelling of historical and projected climate suitability indices

The assembled climate data were used in two mathematical models to develop two geotemporal suitability indices: (1) a temperature suitability index (TSI) tracking relative vectorial capacity and (2) a larval habitat suitability index (HSI) measuring relative availability and potential productivity of mosquito larval breeding sites.

Temperature provides both an upper and lower constraint on malaria transmission, reflecting the ectothermic nature of mosquito and parasite lifecycles. Mathematical models linking temperature to relative vectorial capacity are well established and described elsewhere55. Here we updated a degree-day-based framework56,57 to include recently published data on the A. gambiae complex14. The resulting temperature suitability curve is nonlinear, peaking at 26.4 °C.

To describe the relationship between local rainfall, temperature and humidity and the resulting availability of habitat for oviposition and larval development we discretized a Clausius–Clapeyron-based model of habitat availability used in an established mechanistic model of malaria58 as follows: let Rt denote rainfall volume at time t, so that transient larval habitat is given by the recursion:

$$\rmHabitat(t)=R_t+\frac1\delta _t\rmHabitat(t-1),$$

where δt is the time-dependent temperature and humidity-dependent evaporation rate, which is a function of temperature Tt, humidity Ht and a physical constant C:

$$\delta _t=C\exp \left\-\frac1T_t+273.15\right\\sqrt\frac1T_t+273.15(1-H_t).$$

Then the expected duration of habitat at time t is:

$$\mathrmdur_t=\frac1\log _2\frac1\delta _t,$$

and we may approximate Habitat(t) as HSI(m) for a month m of length |m|:

$$\beginarrayl\rmHSI(m)=\sum _d\in m\fracR_dm\,\min (\rmdur_m,|m|-d)\\ \,\,\,+\sum _d\in m-1\fracR_d\,\max (0,\rmdur_m-|m|+d)\mathbbI(\rmdur_m-1 > |m-1|-d)\endarray$$

where \(\mathbbI\) denotes an indicator variable equal to 1 when the condition is true and 0 otherwise. We augmented this transient larval habitat suitability with a ‘permanent larval habitat’ layer derived from Tasselled Cap Wetness53,59 observations adjusted for local rainfall.

To visually examine the empirical signal of these two climatic suitability indices, we binned PfPR observations into deciles by TSI and HSI (Extended Data Fig. 7). Subsetting observations to those in rural settings, and then further to areas of low insecticidal bednet (ITN) coverage, the variation in PfPR associated with changing TSI and HIS becomes more pronounced.

Preparation of historical geotemporal housing, intervention and contextual data

Malaria control

The scale up of malaria control is responsible for most of the decline in burden in sub-Saharan Africa since 2000 (ref. 28). Geotemporal estimates of historic ITN, indoor residual spray (IRS), SMC and antimalarial treatment coverage were obtained from the Malaria Atlas Project. To account for the nonlinearity in the ITN–PfPR2–10 relationship, ITN coverage was transformed using a pre-defined parametric interaction with estimated pre-intervention-era parasite rate28. The resulting functional form of the ITN–PfPR2–10 relationship was consistent with biological understanding as encoded in mechanistic malaria models60,61. This study did not seek to model possible future trends in intervention coverage. Instead we defined a baseline intervention coverage reflecting present-day levels, and this was used for all future scenarios (with or without disruption due to extreme weather events). To account for the campaign-based nature of ITN distribution we took a 4-year average across 2019–2022 as baseline. For treatment coverage, delivered horizontally, 2022 was taken as baseline for future projections.

Relative abundance of vector species

Malaria ecology varies by mosquito species, with the relationship between the environment and transmission expected to vary between settings with different dominant vectors, even after controlling for interventions and socioeconomic factors. To account for this, we fit species-specific terms in the model, with predictions based on relative abundance of the three dominant vectors in sub-Saharan Africa: A. gambiae (s.s. and coluzzi), Anopheles funestus and Anopheles arabiensis. Estimates of relative abundance of each species were obtained from ref. 39, providing for each 5 × 5 km grid cell a three-way weighting of malaria vector species. We omit explicit modelling of the invasive Anopheles stephensi vector but acknowledge this mosquito represents a substantial emerging threat.

Socioeconomics

Improved housing has been shown to reduce risk of malaria infection62 and is a key mechanism by which socioeconomic development impacts malaria independently of direct malaria investment. We updated existing estimates of the prevalence of improved housing42 using data on characteristics of 1,083,386 households across Africa63 and predictors that include gridded data on population density49, gross domestic product64, land cover65 and travel time66. To account for the lifespan of buildings, a monotonicity constraint (increasing) was applied. We did not seek to model future trends in improved housing, and 2022 was used as the present-day baseline for projections.

Preparation of historical malaria response data

A total of 49,994 geo-located observations of PfPR were collated from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program and other nationally representative surveys63 and systematic literature review41, representing 2.54 million people tested between 1995 and 2021 across 41 African countries. These data were standardized for age (to 2–10 years) and diagnostic type (to light microscopy), consistent with established approaches to modelling these data67.

Characterizing historical climate, housing, intervention and other contextual effects on malaria

We used stacked generalization68 to regress the predictor variables onto PfPR observations. This method, which ensembles out-of-sample predictions from several ‘level 0’ models as predictors in a final geostatistical generalizer, has been shown to outperform standard model-based geostatistics when applied to PfPR data68.

Three ‘level 0’ models were used in this analysis:

-

(1)

Linear model: for observed PfPR y,

$$\beginarrayc\mathrmelogit\,y_s,t \sim \mathrmNormal(\rm\mu _s,t,\sigma _\epsilon ^2)\\ \rm\mu _s,t=U_c[s]+\tilde\beta \prime X_s,t^\mathrmclimate+\tilde\gamma \prime X_s,t^\mathrmcontextual\endarray$$

where Uc[s] was a country-specific intercept, \(X_s,t^\rmclimate\) was a matrix with columns (i) standardized as inh-transformed HSI, cumulative across 2- and 3-month lags; (ii) standardized TSI at 1-month lag, (iii) their multiplicative interaction; (iv) and (v) A. arabiensis relative abundance weighted versions of (i) and (ii); and finally (vi), (vii) A. funestus relative abundance weighted versions of (i) and (ii) (A. gambiae (s.s. and coluzzi) was taken as our reference species for terms (i) and (ii)). \(X_s,t^\rmcontextual\) was a five-column matrix consisting of prevalence of improved housing, the ITN interaction term, IRS coverage, access to effective treatment with an antimalarial and SMC coverage. \(\sigma _\epsilon ^2\) denotes variance of the Gaussian noise term. \(\rmelogit\) denotes the empirical logit.

-

(2)

Generalized additive model: model formula as for meta-model (1), with A. funestus as reference species, and the linear terms for A. gambiae relative abundance weighted HSI, housing, IRS and SMC replaced with penalized cubic splines.

-

(3)

Generalized boosted regression: model formula as for meta-model (1), with interaction term removed and replaced with species-specific terms. Monotonicity constraints were placed on the model terms to prevent spurious results. A total of 1,000 trees were fit, with an interaction depth of four.

These three models were fit to the PfPR2–10 dataset described above, avoiding overfitting by using fivefold cross-validation to generate out-of-sample predictions to be used as fixed effects when training the level 1 generalizer model. For tractability, we modified the stacked generalization approach by, for each level 0 model, generating these hold-out predictions with interventions set to zero. That is, each of the level 0 models provided an (out-of-sample) predictor representing estimated risk in the absence of interventions.

Each intervention class was then included in the geostatistical primary model as a fixed effect. For location s and time t the generalizer model can be expressed, for PfPR ys,t, as:

$$\beginarrayc\mathrmelogit\,y_s,t \sim \mathrmNormal(\eta _s,t,\sigma _\epsilon ^2)\\ \eta _s,t=\mathop\sum \limits_i=1^3\beta _i^\prime X_i,s,t+\mathop\sum \limits_j=1^4\gamma _j^\prime I_j,s,t+Z_s,t\\ Z_s,t \sim \mathcalG\mathcalP\,(0,\Sigma _\mathrmspace\otimes \Sigma _\mathrmtime)\\ \Sigma _\mathrmspace \sim \mathrmMat{\rm \acute\rme }\mathrmrn(5/2),\mathrmPC\,\mathrmprior\,:P\left(\mathrmrange < \frac7\rm\pi 180\right)=0.1,\\ P(\sigma _\mathrmspace > \,\log (1.1))=0.01\\ \Sigma _\mathrmtime \sim \mathrmAR(1)(\rho ),\mathrmPC\,\mathrmprior\,:P(\rho > 0.7)=0.99,\\ P(\sigma _\mathrmtime > 0.05)=0.01\\ \beta _i^\prime \sim N(0,1)\\ \gamma _1^\prime \sim N(4,0.1)\\ \gamma _2^\prime \sim N(0.5,0.1)\\ \gamma _j^\prime \sim N(0.5,1),j=3,4\endarray$$

where Xs,t are the out-of-sample zero-intervention predictions forming the level 0 stack, Is,t is the vector of malaria control coverage (interacted with pre-intervention-era PfPR, in the case of ITNs) at pixel s at time t, Z is spatio-temporal random field with separable Matérn-5/2 spatial and AR(1) temporal kernel. The meta-learner slopes β′ were non-negative—a sufficient condition for stacked generalization68. Following previous approaches to modelling PfPR, we used a Gaussian likelihood and empirical logit transform to ensure well-specified posterior distributions69. The geostatistical model was fit in R 4.2.0 using INLA v.22.12.16 (refs. 70,71). Fitted parameters for both the level 0 models and geostatistical generalizer model are given in the Supplementary Information.

This modelling approach estimates the empirical associations between each predictor and PfPR2–10. Counterfactual predictions may then be constructed by modifying covariates of interest, holding other variables constant, and using the fitted parameters to generate predictions of PfPR2–10, which can then be differenced from a baseline prediction in which all variables were held constant. By repeating the procedure for each predictor and combination of predictors, we estimate the change in response attributed to change in covariates, conditioned on the model structure and observed data.

Validation

In-sample observed versus fitted correlation was 0.86 and mean absolute error was 8.5% at cluster and 1.1% at DHS survey aggregate. Verification of out-of-sample predictive ability using fivefold cross-validation yielded out-of-sample correlation of 0.83, mean absolute error of 9.5% (2.5% DHS survey out-of-sample aggregate). Further validation details are provided in Supplementary Information section 5.2.

Generation of future scenarios of extreme weather events

Scenario-based projections of flood events

Random Forest models were developed to predict flood occurrence, extent and duration. The training set consisted of historic flood events extracted at 230-m spatial resolution from Floodbase43, aggregated to Pfafstetter level 4 basin and over-sampled to reduce bias arising from data imbalance. A binary classifier was trained on historic level 4 basin flood occurrence using predictors that included rainfall and Atlantic and Indian Oceans sea-surface temperatures (see Supplementary Information Table 7 for a full description of 27 predictors).

Flood extent (in square kilometres) and duration were modelled probabilistically with similar predictors (see Supplementary Tables 8 and 9 for full description).

The performance of the three flood models was assessed using a 30% test set. The frequency model correctly classified 82% of occurrences and 85% of non-occurrences (area under the curve 0.84), whereas the duration and extent models had R2 values of 0.83 and 0.81, respectively.

We calculated GCM-specific future projections of flood occurrence, duration and extent by level 4 basin for 2024–2049. For each GCM, the simulated period 2024–2026 was resampled to generate future counterfactual scenarios representing present-day climate flood frequency and extents. To downscale the predicted level 4 basin-level extents, high-resolution occurrence data of historic floods43 were combined with a hydrological model72 to obtain, for each grid cell, flood propensity scores. For each flood event, grid-cells were then flooded from highest to lowest flood propensity until the predicted extent was reached. Projections were ceteris paribus, with land use variables held constant.

Scenario-based projections of cyclones

Historical Indian Ocean cyclone data (track morphology, start and end date, wind speeds) were obtained from IBTrACS44. Storms in the IBTrACS database coming within 50 km of the coast of Africa were included, yielding a training set of 192 tropical depressions, storms and cyclones since 1980. Future scenarios of cyclone genesis and trajectories were generated using the Imperial College Storm Model (IRIS) dataset45—a 10,000-year synthetic dataset of statistical characteristics of cyclones, adjusted with climate data from the downscaled and bias-corrected CMIP6 models. Following the IRIS method, we modelled cyclone generation events (commencing from the point of lifetime maximum intensity (LMI)), with probability of occurrence at each location in the southern Indian Ocean modelled as Poisson distributed with spatial variation learned using coordinates of historic LMI locations. From these LMIs, synthetic tracks were generated by perturbing historical tracks using forecast cone uncertainty.

The maximum sustained wind speeds at LMI were calculated using climate data and thermodynamic constraints, including potential intensity. After LMI, the model simulated intensity decay separately for ocean and land. Track steering and wind speed calculations used decay rates based on observed data and projected climate variables. Cyclone size was calculated dynamically, starting from LMI using a radial wind profile evolving along the track, capturing intensity-dependent size changes. Minimum pressure during the decay phase was modelled using a unified pressure-wind relationship, influenced by storm size and latitude. These components together generated synthetic cyclone datasets that replicated key physical and statistical characteristics of observed cyclones.

Only category 1 or greater cyclones making landfall in Africa were included in our final scenarios. Cyclones were assumed to begin at LMI, and tracks were terminated when modelled wind speed fell below tropical storm threshold (63 km h−1). A counterfactual future scenario of cyclones reflecting present-day climate conditions was generated by resampling past cyclones, with Poisson rates of each category given by their frequency since 1980. Impact footprints were calculated based on R18—the radius of damaging winds.

Parameterizing impact of extreme weather events on housing and interventions

Extreme weather events were modelled as disrupting access to three key suppressants of malaria transmission: (1) improved housing, (2) indoor vector control tools and (3) access to antimalarial treatment. The magnitude and duration of disruption was parameterized for each event class and severity on the basis of a mixed-methods approach: a literature review extracted 22 studies from the peer-reviewed and grey literature documenting the impact of extreme weather events (Extended Data Table 2). This process was augmented with 34 expert interviews. Parameters derived from this exercise were used to define recovery curves to be applied within footprints of extreme events, shown schematically in Extended Data Fig. 2, with parameters described in Extended Data Table 3. Acute and persisting impacts were differentiated, with the latter parameterized sigmoidally by time to 50% and 99% recovery. Uncertainty in the magnitude of disruption was then represented using a 50–150% scaling around the consensus central values.

Projecting impact of extreme weather events on housing and interventions

Disruptions to healthcare accessibility

Present-day access to effective treatment (EFT) for clinical malaria at location s was estimated using a composite of three surfaces generated by the Malaria Atlas Project41: probability of care-seeking cs, use of antimalarial drugs \(p_s^\rmdrug\), and drug- and location-specific therapeutic efficacy \(E_s^\rmdrug\):

$$\rmEFT_s=c_s\sum _\rmdrugp_s^\rmdrugE_s^\rmdrug,$$

where ‘drug’ is one of artemisinin combination therapy (the first-line treatment for falciparum malaria in Africa), amodiaquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, chloroquine or quinine.

Using a database of health facility geolocations73, a transport network model for Africa74 and a least-cost-path journey time algorithm66, we determined present-day (disruption free) travel time to health facilities for each grid cell. A bi-exponential relationship between these travel times \(\mathcalT_s\) and 104,516 geo-located observations of propensity to seek care for fever was fitted, resulting in the function:

$$\rmt\_\rmdecay(\mathcalT_s)=0.1451\,\exp (-0.0798\mathcalT_s)+0.5396\,\exp (-0.0008\,\mathcalT_s).$$

Health facilities located within the footprint of extreme weather extents were considered non-functional during acute impacts, with the proportion of facilities in each 5 × 5 km grid cell remaining non-functional in the post-acute period sampled from a binomial distribution, with probability of closure given by intersecting the appropriate recovery curve with a time-since-last-event surface. Given these dynamic functional facility geolocations, we recalculated travel time to health facilities for each scenario, by month, to 2050. In addition to facility closures, damage to road infrastructure was parameterized as travel time penalties derived from the recovery curves and time-since-event surfaces overlaid on the OpenStreetMap road network74. Off-road travel time was recalculated by perturbing a friction surface73 in the same way. The result was scenario-specific travel time to healthcare \(\mathcalT_s^\rmscenario\). We then calculated care-seeking penalties relative to undisrupted conditions, so that at location s and time t:

$$\rmEFT_s,t^\rmscenario=\frac\rmt\_\rmdecay(\mathcalT_s,\,t^\rmscenario)\rmt\_\rmdecay(\mathcalT_s^\rmno\,\rmdisruption)c_s\sum _\rmdrugp_s^\rmdrugE_s^\rmdrug.$$

Antimalarial efficacy, proportional usage of different antimalarials and secular variation in care-seeking behaviour were held constant, as was the undisrupted transport network.

Disruptions to ITN coverage and access to improved housing

ITN campaigns were simulated every three years on 1 January, commencing in 2025. As we aimed to model unmitigated impacts of extreme weather events, disrupted ITN coverage did not return to normal until the next simulated campaign. ITN access was assumed to be lost if access to housing was acutely disrupted. Access to improved housing was directly perturbed using the derived recovery curve.

Projecting ecological and disruptive effects of climate change

A set of scenarios was defined to derive the ecological, disruptive and combined impacts of climate change by the 2040s; these are described in Extended Data Table 1.

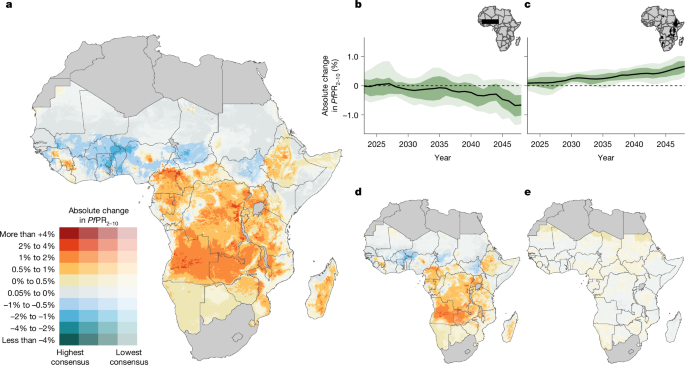

To model ecologically driven impacts of climate change we generated estimates of monthly PfPR2–10 from 2019 to 2049 for each of the 14 ensemble members. A climate-change-free scenario (E0) was defined as the ensemble mean of median PfPR2–10, 2019–2022, and corresponding scenario of future changes in ecological suitability (E1) as ensemble mean of median PfPR2–10, 2040–2049. The ecological impact of climate change was thus estimated by the difference E1 − E0 (Fig. 1a).

We derived counterfactual and SSP 2-4.5 extreme weather event scenarios for a tractable subset of three GCMs: ACCESS-CM2, EC-Earth3-Veg-LR and MPI-ESM1-2-LR. For each ensemble member, two time-series of spatial PfPR2–10 projections were calculated. Scenario D0 was defined as the (three-GCM) ensemble mean of median PfPR2–10, 2040–2049, generated with present-day TSI and HSI as in E0 and with extreme events simulated as occurring at present-day frequency. Still holding TSI and HSI at present-day levels, SSP 2-4.5 projections of changing extreme weather event frequency were imposed to derive scenario D1, so that the difference D1 − D0 isolated the impact of disruptive events due to climate change (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Table 1).

Ecological and disruptive impacts were combined by defining C0 equal to D0 (that is, present-day climate suitability and extreme event frequency). SSP 2-4.5 projections of changing climate suitability indices (as in E1) and changing extreme weather frequency (as in D1) were combined to generate C1, the (three-GCM) ensemble mean of median PfPR2–10, 2040–2049. The combined ecological and disruptive impacts were then calculated as C1 − C0 (Fig. 2b).

Projected PfPR2–10 for each scenario was converted to clinical case incidence using an established natural history model48. Gridded population projections consistent with SSP 2-4.5 were used to generate estimates of absolute cases49. Projected time-series of clinical cases and mortality were scaled to align with 2022 official World Health Organization estimates, as reported in World Malaria Report 2023 (ref. 50).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.