Dementia is a growing global challenge, with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) being the most common cause, characterized by ADNCs, encompassing brain deposits of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaque and neurofibrillary tau tangles. The prevalence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is well established2,3, but the prevalence of ADNCs in general populations remains uncertain. With the advent of drugs capable of reducing Aβ plaque pathology and slowing cognitive decline4,5, accurate knowledge of ADNC prevalence is essential for anticipating the number of individuals eligible for treatment and estimating future health-care demands and associated costs. A recent review has reported an overall prevalence of 22% ADNCs in all people 50 years of age and older globally2. However, studies examining the prevalence of ADNCs are typically enriched, including relatively small clinic-based samples, which tend to differ regarding important clinical and demographic features compared with general populations. Such studies may thus report inflated or deflated rates of AD pathology.

Until recently, ADNCs could only be verified in vivo using cerebrospinal fluid analysis or molecular positron emission tomography (PET), substantially hindering its evaluation in large population-based studies. Minimally invasive blood-based markers, particularly plasma phosphorylated tau at threonine 217 (pTau217), that have high accuracy for ADNCs have recently become available but have not yet been used in large community-based studies6. In this study, we capitalized on the large Norwegian population-based Trøndelag Health (HUNT) study7,8, with 11,486 blood samples of participants 58 years of age and older, to explore the following research questions: (1) what the prevalence of ADNCs in the population 58 years of age and older across age and sex groups is; (2) what the association between ADNCs and demographics, cognition, educational level, apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε2, ε3 or ε4 status and comorbidities is; and (3) what proportion of those 70 years of age or older is eligible for disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) according to current recommendations9,10.

The HUNT study has been ongoing for four decades, with a new wave taking place in the same population every 10 years, thus four waves exist so far. In this nested cross-sectional study, we included 2,537 individuals from HUNT3 (age range of 58–69.9 years, 51.2% women) and 8,949 from HUNT4 (age range of 70 years and older (hereafter the 70+ group), 53.6% women). Subsequent diagnostic history was considered when deciding who to approach for inclusion in HUNT3. Although a blood sample was provided in both surveys, the HUNT4 70+ cohort also underwent a standardized clinical assessment for a diagnosis of dementia and MCI11 (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information, ‘Assessment of cognition, physical performance, anxiety, depression, neuropsychiatric symptoms and activities of daily living’). The presence of ADNCs was established by measuring plasma pTau217 levels with a previously validated commercial kit (ALZpath p-Tau 217 Advantage PLUS, Quanterix)1. We used a two cut-off approach as recommended by the Global CEO Initiative on Alzheimer’s Disease12 to categorize individuals as ADNC negative (less than 0.40 pg ml−1), intermediate or positive (0.63 pg ml−1 or more), as previously described1. The agreement between elevated plasma pTau217 concentration and the presence of notable amounts of plaques and tangles at post-mortem examination has been previously found to be very high13. For terminological clarity, in the remainder of this article, the term ‘ADNC’ refers specifically to the presence of elevated plasma pTau217 concentration, used as a surrogate marker for ADNCs.

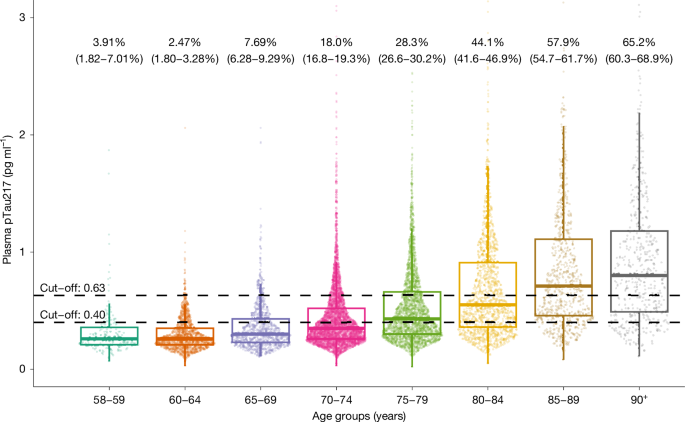

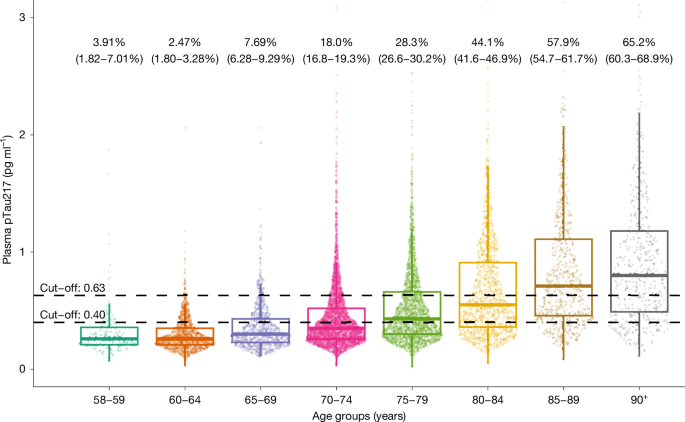

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are shown in Extended Data Table 1. The estimated proportion of people with and without ADNCs in different age groups is shown in Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2. There was a stepwise increase in the proportion of ADNCs across age groups; the proportion was 33.4% in the 70+ group. There was a significant association between ADNCs and cognitive diagnosis. Among individuals with dementia, 60% had ADNCs (that is, AD dementia), compared with 32.6% of those with MCI (that is, prodromal AD) and 23.5% in the cognitively unimpaired group (that is, preclinical AD). The proportion with ADNCs increased with age in each of the cognitive groups. ADNCs were ruled out based on plasma pTau217 concentrations being below the lower cut-off in 19.4% of the dementia group, 41% of the MCI group and 50.1% of the cognitively unimpaired group (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Table 3). Depending on age, 13.5–27.6% of participants had plasma pTau217 concentrations in the intermediate range, with only minor differences between the cognitively unimpaired, MCI and dementia groups (Extended Data Tables 2 and 3). Weighted estimated proportions of ADNCs in the respective clinical cognitive subgroups are shown in Extended Data Table 4.

Individual dots represent plasma pTau217 concentrations (n = 2,537 participants from HUNT3 and n = 8,949 participants from HUNT4 70+). Percentages (95% confidence interval) are estimates of how many in each age group have AD neuropathology, defined by plasma pTau217 concentration of 0.63 pg ml−1 or more. The lower cut-off of 0.40 pg ml−1 is also shown. The horizontal line in each box represents the median, and bottom and top edges delineate the second and third quartiles. The bottom whisker represents the first quartile, and the top whisker denotes the fourth quartile. Concentrations above 3 pg ml−1 are not shown.

Percentages (with 95% confidence intervals; colour-coded to match the box plots) are estimates of how many in each cognitive group have AD neuropathology, defined by plasma pTau217 concentration ≥ 0.63 pg ml−1. The lower cut-off of 0.40 pg ml−1 is also shown. n = 8,949 participants from HUNT4 70+. The horizontal line in each box represents the median, and top and bottom edges delineate the second and third quartiles. The bottom whisker represents the first quartile, and the top whisker denotes the fourth quartile. CU, cognitively unimpaired.

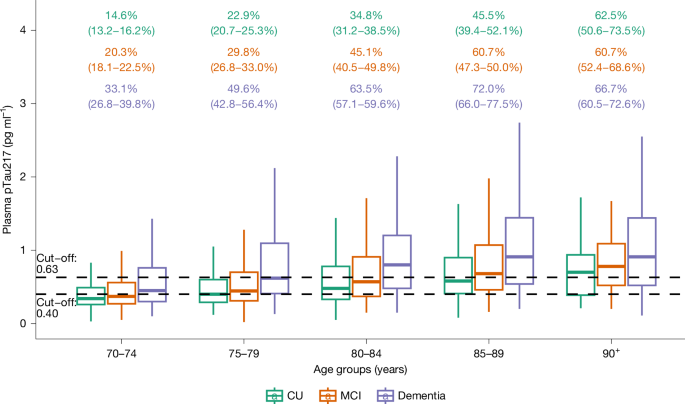

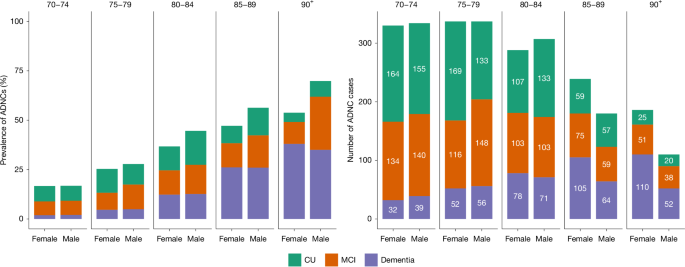

The estimated prevalence of preclinical AD, prodromal AD and AD dementia in the 70+ study population is shown in Fig. 3 and Extended Data Table 5. The estimated prevalence of AD dementia consistently increased with age, whereas the prevalence of preclinical AD increased from the 70–74 year age group to the 80–84 year age group before decreasing in the oldest old (those aged 85 years or older (the 85+ group)). The prevalence of prodromal AD remained stable after 80 years of age (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Left, the percentage of participants with ADNCs, defined as plasma pTau217 concentration ≥ 0.63 pg ml−1. Stacked bars represent the estimated proportions of ADNCs. Right, absolute numbers of study participants with ADNCs. Colours represent different levels of cognitive effects. The values are stratified, on the x axis, by sex. The numbers displayed at the top of the graphs are age groups in years.

In the 80–89 year age group, men had a slightly higher estimated prevalence of ADNCs than women, mainly due to a higher prevalence of early-stage AD (preclinical and prodromal AD), although cognitive subgroup differences were not statistically significant. There was no sex difference in the estimated prevalence of AD dementia in any of the age groups. Details can be found in Extended Data Table 5 and Extended Data Fig. 2.

Estimated ADNC prevalence was higher among individuals with one (46.4%) or two (64.6%) APOE ε4 alleles than in those with none (27.1%; Extended Data Table 6). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was inversely associated with plasma pTau217 concentration in individuals with eGFR < 51 ml min−1 per 1.73 m2 (Extended Data Fig. 3). There was no significant association between ADNCs and self-reported cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, cancer, migraine, psoriasis, kidney disease, rheumatoid arthritis and gout, when adjusting for age, sex, APOE ε4 allele count, cognition, serum creatinine levels and education level (Extended Data Table 7).

Estimated ADNC prevalence was lowest among individuals with tertiary education, highest among those with primary education and intermediate in those with secondary education, with differences becoming more pronounced with age. For those with primary education, ADNC prevalence was higher in women than in men, whereas in those with secondary and tertiary education, men had a higher estimated ADNC prevalence than women (Extended Data Fig. 4).

On the basis of the current eligibility criteria for DMTs4,5, out of a total of 8,949 participants in the 70+ group, 909 (10.2%) fulfilled the eligibility criteria for DMTs (Extended Data Fig. 5), whereas the weighted estimate for the entire 70+ population was 11.1%.

Positive and negative predictive values (PPVs and NPVs, respectively) were examined in an exploratory analysis based on previously reported sensitivity and specificity metrics for pTau217 for ADNCs. The PPV increased with age-specific prevalence, from 59.9% (70–74 years of age) to 92.6% (90 years of age or older (the 90+ group)), whereas the NPV decreased from 97.9% to 84.9%. Overall, the PPV and NPV were 77.4% and 95.4%, respectively. Under optimism correction, the PPV and NPV were attenuated to 71.9% and 92.9% overall, with ranges of 52.9–90.4% (for PPV) and 78.3–96.8% (for NPV) across age strata, consistent with higher PPV and lower NPV at higher prevalence (Extended Data Table 8).

In this large, Norwegian population-based cohort study, the proportion of individuals with ADNCs, as measured with plasma pTau217 concentration, increased with age, from under 8% in people 58–69 years of age to 65% in those over 90 years of age. Among the 70+ population, 10% had preclinical AD, 10.4% had prodromal AD and 9.8% had AD dementia. ADNCs were more prevalent in individuals with lower education and those with APOE ε4 alleles. ADNCs were inversely associated with eGFR < 51 ml min−1 per 1.73 m2. It has previously been shown that age, APOE ε4 status and renal dysfunction are associated with pTau217 concentrations, but that these factors only marginally alter the clinical performance of pTau217 as a marker for ADNCs14,15. The two plasma pTau217 cut-offs used to assess the prevalence of ADNCs (lower cut-off with 95% sensitivity and upper cut-off with 95% specificity) were applied independent of age1. Age-dependent increases in plasma pTau, independent of ADNCs, have been discussed in the literature; however, current evidence does not support this association6.

Although the prevalence of AD dementia among the youngest cognitively assessed age group in our study (70–74 years) was similar to that reported in a recent literature review (2% versus 1.7%)2, we found a higher prevalence of AD dementia in the older age groups (for example, 85–89 years: 25.2% in our study, compared with 7.1% in the review). By contrast, the prevalence of preclinical AD in the youngest age group (70–74 years) was much higher in the review (22.4% for men and 22.2% for women) than in our study (7.6% for men and 7.9% for women). It is possible that, compared with the unselected community-based cohort in our study, the more selected cohorts included in the review over-recruited cognitively healthy people at high risk for AD, and under-recruited older people with dementia. Participants under 70 years of age were not cognitively assessed; thus, their clinical status remains undetermined.

Blood-based AD biomarkers are increasingly being utilized for considering people eligible for treatment with the new anti-AD drugs, which have been recently approved in several countries, including the USA and Europe. On the basis of the current eligibility recommendations for these drugs9,10, we found that 11% of people 70 years of age or older in the study population would potentially be eligible. Such treatments carry risks that would have to be carefully weighed against any potential benefits in each individual16.

On the basis of having plasma pTau217 concentrations below the lower cut-off, ADNCs were ruled out in 41% of the MCI group and 19.4% of the dementia group. Thus, in these groups, cognitive impairment is probably due to causes other than AD. The higher prevalence of ADNCs in people with one or two than with none APOE ε4 alleles is in line with previous findings17,18. The prevalence of ADNCs was slightly higher in men than in women in the 80–89 year age group. There was no sex difference in the prevalence of plasma pTau217-verified AD dementia in any age group. Several clinical studies have reported a female predominance of dementia19, and previous HUNT data have reported a slightly higher prevalence of dementia in women than in men, but only in those over 85 years of age, whereas MCI was more common in men than in women11. The recent review also reported a higher proportion of preclinical AD in men, but a higher prevalence of AD dementia in women2. Thus, the most recent evidence does not seem to support previous reports of higher ADNC prevalence in women.

Having a lower level of education was clearly associated with higher ADNC prevalence, especially in the older age groups. This supports the theory of a protective effect of education, for example, by means of increasing cognitive reserve20. We did not assess potential confounding factors such as smoking, obesity, physical inactivity and excessive alcohol consumption21, which may attenuate the association between education level and ADNCs.

There was no association between self-reported somatic morbidities and plasma pTau217 concentrations above the upper cut-off when adjusting for confounding factors. Previous research has shown that vascular disease can both cause dementia and increase the odds that AD pathology manifests as AD dementia22,23. We have not studied the possible synergistic effect of ADNCs and comorbidities on cognition.

This study has several strengths. It is the largest population-based study of ADNCs. The clinical diagnosis of MCI and dementia was based on a prospective standardized clinical assessment. Analysis of ADNCs was based on an accurate assay performed in a laboratory with extensive experience and expertise using state-of-the art technologies. Until recently, the absence of robust and scalable pTau217 assays meant that research cut-offs for blood-based markers were specific to each cohort and did not generalize effectively during external validation. However, the assay used in this study has shown strong performance in external validation across independent cohorts1.

Plasma pTau217 reflects both phosphorylated, soluble tau in the context of Aβ pathology24 and aggregated tau pathology. Elevated concentrations of soluble pTau217 can occur decades before the onset of aggregated tau25, correlate strongly with the severity of AD pathology and with clinical progression, and are considered specific for AD1. Thus, plasma pTau217 has shown good discriminative accuracy for distinguishing between pathology-confirmed AD and other tauopathies such as frontotemporal lobar degeneration26,27, traumatic encephalopathy syndrome28, primary age-related tauopathy29 and progressive supranuclear palsy13.

Plasma pTau217 concentration has been shown to have the highest predictive values of the blood-based AD markers30. Although recent studies indicate that the ratio of plasma pTau217 to the 42-amino-acid-long form of Aβ (Aβ42) can reduce intermediate test results and may slightly increase diagnostic accuracy in well-controlled research cohorts31,32,33, these findings do not directly translate to large population-based studies such as HUNT. Plasma Aβ42 concentration is highly sensitive to pre-analytical variables, which often deviate from Alzheimer’s Association guidelines in population cohorts34, leading to falsely increased pTau217:Aβ42 ratios35.

This study used a two-cut-off method1. Depending on age, 13.5–27.6% of the study population had plasma pTau217 concentrations in the intermediate range, here defined as plasma pTau217 values between 0.40 and 0.63 pg ml−1 and would thus require further examination to clarify their ADNC status. In an ideal scenario, individuals in the intermediate group would undergo cerebrospinal fluid analysis or PET imaging to obtain a more definitive diagnosis, although these methods also can yield intermediate, ‘grey zone’ results36,37. Regional molecular PET patterns can be an important indicator of observed or expected clinical symptoms38. However, recognizing that such evaluations are often not routinely available, a feasible follow-up strategy would be to repeat plasma biomarker testing after, for example, 1 year12. The presence of an intermediate zone is an expected and intrinsic feature of continuous biomarker distributions when applied to binary clinical outcomes such as ADNCs. Rather than a limitation, this zone reflects biological and clinical heterogeneity, particularly in population-based cohorts. A substantial proportion of individuals in the intermediate range probably exhibit ADNCs.

The participation rate in HUNT4 70+ was 51.1%, and we are unaware of other similarly large population-based studies with such a high participation rate. Because of limited funding, we were unable to analyse blood samples from all participants 58–69 years of age in HUNT3, but we attempted to adjust for a potential selection bias (see Extended Data Table 9). The cross-sectional design might underestimate amyloid abnormality as opposed to lifetime risk estimates. Furthermore, although nearly 90% of HUNT4 70+ participants provided a blood sample, 10% did not. The proportion not providing a blood sample was higher in the dementia group, but we adjusted for this in our analysis, as well as for participation bias in HUNT4 (see Extended Data Table 9).

This study has some limitations. Medical diseases were self-reported and thus might not accurately reflect the degree of comorbidities. Previous findings indicate a high NPV and moderate PPV for self-reported diseases in the HUNT study compared with diagnoses recorded in regular clinical care7. The HUNT study does not collect data on ethnicity, but the population in this region in 2017 included less than 5% of individuals who are immigrants or Norwegian born to parents who immigrated from Africa, Asia, the Middle East or South America, and thus the findings are relevant for a mainly white Norwegian population. Dementia varies in different ethnic groups and thus the prevalence of ADNCs may also differ in other populations2.

The predictive value of a diagnostic test varies with the disease prevalence. Thus, as has been demonstrated, when the likelihood of ADNCs is high, for example, in older individuals, the PPV is high, whereas the NPV is lower, that is, there is a risk of false-negative results30. This analysis is not a substitute for internal validation and has key limitations: (1) the commutability of sensitivity and/or specificity from external cohorts is assumed; (2) circularity is possible because prevalence is estimated from the same biomarker; and (3) we do not model age-specific shifts in sensitivity and/or specificity or spectrum effects.

In conclusion, we present prevalence estimates of ADNCs in a large, Norwegian population-based cohort. Among individuals 70 years of age or older, 33.4% exhibited ADNCs, with 10% classified as preclinical AD, 10.4% as prodromal AD and 9.8% as AD dementia. Compared with previous studies with smaller, less representative cohorts, our findings indicate a higher prevalence of AD dementia in older individuals and a lower prevalence of preclinical AD in younger age groups.