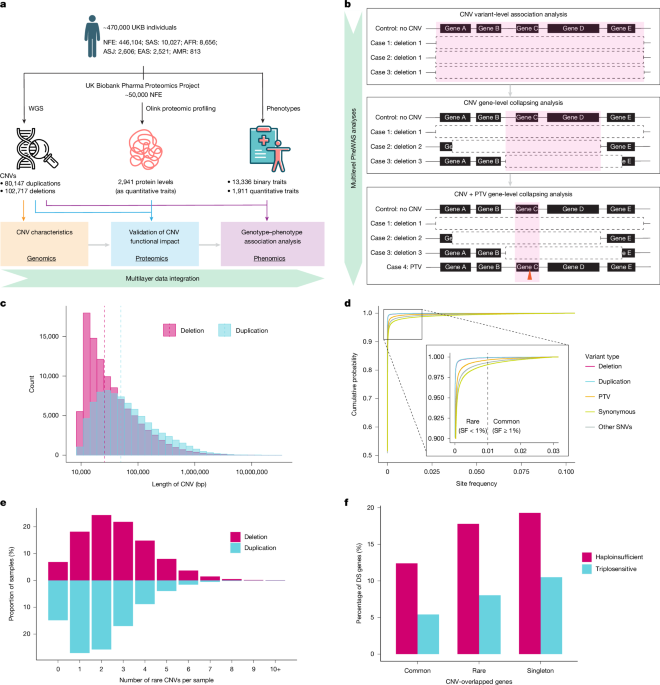

UKB resource

The protocols for the UKB are overseen by the UKB Ethics Advisory Committee; for more information, see https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/ethics and https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Ethics-and-governance-framework.pdf. Informed consent was obtained for all participants. The Northwest Research Ethics Committee reviewed and approved UKB’s scientific protocol and operational procedures (REC reference no. 06/MRE08/65). Data for the present study were obtained and research was conducted under UKB application license nos. 24898 and 68574.

WGS, sample selection and CNV discovery

Whole-genome-sequencing (WGS) data for 490,560 UKB participants were generated by deCODE Genetics and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute as part of a public–private partnership involving AstraZeneca, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Wellcome Trust Sanger, UK Research and Innovation, and the UKB. The WGS sequencing and quality control methods have been previously described24. Briefly, genomic DNA underwent paired-end sequencing on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instruments with a read length of 2 × 151 and an average coverage of 32.5×. The DRAGEN 3.7.8 variant-calling pipeline workflow has also been described in detail in ref. 24, including running mode, parameters used in DRAGEN and computational requirements.

A set of filters were applied, including removing samples (1) with consent withdrawals; (2) less than 2% match with whole-exome sequencing and array data; (3) sequences identified as sample duplicates with multiple birth events; (4) more than 4% contaminated sequences (verifybamid_freemix ≤ 0.04) using VerifyBAMID; (5) low CCDS coverage (fewer than 94.5% of CCDS r22 bases covered with at least ten-fold coverage); and (6) coverage uniformity outliers with coverage uniformity > 0.433 (more than six times the interquartile range). We used peddy53 and 1000 Genomes Project data to classify ancestries (peddy_prob ≥ 0.9) using the gnomAD classifier52 to subdivide European-ancestry samples into those of non-Finnish (NFE) and Ashkenazi Jewish (ASJ) ancestries. We performed further quality control on NFE ancestry samples using peddy-derived principal components removing samples that fell outside four standard deviations from the mean over the first four principal components. A workflow of sample filtering is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

DRAGEN version 3.7.8 was used for whole-genome CNV calling with self-normalization. Input was provided as a BAM file aligned to the hg38 reference genome with alt-aware support. Quality control included coverage analysis across multiple genomic regions and cross-contamination checks. The CNV calling pipeline consists of five key modules. First, the TargetCounts module bins read counts and other alignment signals. Next, the BiasCorrection module adjusts for systematic biases. The Normalization module then determines normal ploidy levels and normalizes the sample. After normalization, the Segmentation module detects breakpoints in the signal. Finally, the Calling/Genotyping module scores, qualifies and filters putative events to identify CNVs. The final call file contains segments of duplication, deletion and copy-neutral events. In the present study, we only examined regions with copy number loss or gain. Full details of DRAGEN variant calling have been previously described24.

Olink proteogenomics study cohort

The Olink proteomics study cohort has been described in detail in previous publications21,22,23. In the present study, we analysed 49,736 samples with available paired-genome sequence data. In total, 2,941 plasma proteins were included in the analyses.

Phenotypes

We studied two main phenotypic categories: binary and quantitative traits taken from the April 2023 data release that was accessed on 28 June 2024 as part of UKB applications 68601 and 65851. To parse the UKB phenotypic data, we used our previously described PEACOK package, available at https://github.com/astrazeneca-cgr-publications/PEACOK. A detailed description can be found in a previous publication3. In total, we studied 13,336 binary and 1,911 quantitative phenotypes. As previously described, for all binary phenotypes, we matched controls by sex when the percentage of female cases was significantly different (Fisher’s exact two-sided P < 0.05) from the percentage of available female controls. This included sex-specific traits for which, by design, all controls would be the same sex as cases3. All phenotypes and corresponding chapter mappings for all phenotypes are provided in Supplementary Table 1; generation of the composite phenotypes (prefixed ‘unions’) has been described by Wang et al.3. Seven quantitative traits related to leukocyte telomere length are marked with tl in the field_id column and described31 in the plain_english_name column in Supplementary Table 1.

Sample and CNV quality control

On the basis of on DRAGEN raw CNV calls with size > 10 kb, we performed a series of post hoc sample and variant quality control steps to reduce false positives and false negatives. Size > 10 kb is one of the DRAGEN recommended filters for PASS CNVs.

Sample quality control before CNV post hoc quality control

Samples with haematological malignancies are more likely to exhibit mosaic copy number alterations, which may be incidentally detected by germline CNV callers. In addition, the DRAGEN CNV caller is not designed for detection of whole-chromosomal aneuploidies. Therefore, we excluded samples with known haematological malignancies or chromosomal abnormalities or autosomal aneuploidies from our analyses.

The DRAGEN ploidy caller can detect aneuploidy and chromosomal mosaicism in mammalian germline samples from WGS data. We identified samples with autosomal aneuploidy by examining deletion or duplication calls across chromosomes. Specifically, we flagged a sample for autosomal aneuploidy if it had a PASS status for a deletion call with a normalized depth of coverage < 0.8, or a duplication call with normalized depth of coverage > 1.4. The final sample cohort included six genetic ancestry groups: 446,104 (94.77%) NFE; 2,606 (0.55%) ASJ; 8,656 (1.84%) AFR; 2,521 (0.54%) EAS; 10,027 (2.13%) South Asian (SAS); and 813 (0.17%) admixed American (AMR).

CNV post hoc quality control

Excluding CNVs from problematic regions. Short-read sequencing of the human genome is known to contain regions of low mapping quality, which present challenges for accurate calling of CNVs. To reduce the number of false-positive calls, we adopted a stringent approach. Specifically, we excluded CNVs showing more than 50% overlap with regions marked by N-masks, segmental duplications, simple repeats and the major histocompatibility complex12. Use of these exclusion criteria enhances the reliability of CNV identification by reducing potential artefacts associated with known challenging genomic regions. In addition, considering the challenges of calling CNVs on sex chromosomes54, such as variable ploidy and high repeat content, we also excluded sex chromosome CNVs from our analyses.

Recalibrating CNV quality score. Owing to variations in sequencing coverage among different genomes, the same CNV may receive distinct quality scores (QUAL) in different samples. Consequently, applying a QUAL cutoff to exclude low-quality CNVs may result in filtering out true CNVs from samples with low coverage while retaining them in samples with high coverage, potentially leading to false negatives. To address this issue, we implemented a recalibration of QUAL for each CNV, using the median QUAL value of the same CNVs across all samples. This approach emulates the concept of population-wide genotyping but uses raw CNV calls instead of BAM/CRAM files.

Optimizing CNV QUAL cutoff. Instead of using the default QUAL cutoff (QUAL ≥ 10) from the DRAGEN CNV caller to filter out false-positive CNV calls, we determined the optimal QUAL threshold through a receiver operating characteristic analysis. This aim of this analysis was to minimize the de novo CNV rate while maximizing the number of CNVs identified. Specifically, we evaluated QUAL thresholds ranging from 0 to 150 using data from 935 parent–child trios. For each threshold, we calculated two key metrics: the de novo CNV rate, defined as the proportion of CNVs detected in the proband but absent from both parents; and the total number of unique CNVs identified across the 935 trios (Supplementary Fig. 15). To reduce the risk of in-sample overfitting, we applied ten-fold cross-validation across individuals. Finally, we used QUAL = 35 as the threshold for both deletions and duplications.

Merging highly overlapping CNVs across samples. To account for variability in CNV breakpoint detection across samples when using read-depth-based algorithms, we adopted a strategy55 to merge CNVs that were highly overlapping in genomic coordinates. Specifically, we first compiled a list of all unique CNV events across samples. We then calculated the pairwise genomic overlap between CNVs, and any pair with more than 70% reciprocal overlap was grouped into the same CNV cluster. Within each cluster, the largest CNV was designated as the index CNV site. All samples with CNVs in the same cluster were then assigned to this index CNV site. For downstream analyses, we used the index CNV to represent each merged cluster, reducing redundancy and improving consistency in CNV representation across individuals. The index CNVs were denoted as ALT:CHROM-START-END.

Sequencing site effect. In total, 470,727 whole-genome sequences were obtained from four distinct sequencing sites. Our expectation was that the site frequency of CNVs should be directly proportional to the number of samples sequenced by each batch. An elevated site frequency of a CNV, relative to expectations, may indicate the presence of a batch effect, necessitating its removal from the call set. To assess this, we computed the cosine similarity between the sample numbers from the four sites and the observed CNV numbers from each site. We established that a CNV was linked to a batch effect if the cosine similarity was less than 0.9. Four batch-associated CNVs were identified and excluded from the downstream analysis (Supplementary Table 25).

Somatic CNVs. Although we systematically excluded samples with haematological malignancies, some other samples exhibited clonal haematopoiesis, wherein somatic CNVs in a substantial clone might be mistaken for germline variants. To address this, we leveraged the correlation between somatic CNVs and age to identify potential somatic mutations. Using an adjusted P value cutoff of 0.05, we found no evidence of recurrent CNVs in our call set being of somatic origin. Our analysis suggests that somatic CNVs occurring randomly in a limited number of samples lack the statistical power to demonstrate associations with specific diseases.

Outlier samples

After CNV variant quality control, we assessed whether any samples were outliers in terms of CNV load per genome. We counted total CNVs, deletions, duplications and heterozygous CNVs and calculated the common/rare CNV ratio. Samples were labelled as outliers if their count for any class was more than six times the interquartile range above the third quartile across all samples for that CNV group. In total, 1,038 samples were removed from the downstream analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Relatedness pruning

We used the ukb_gen_samples_to_remove() function from the R package ukbtools (v.0.11.3)56 to choose a subset of individuals within which no pair had a kinship coefficient exceeding 0.0884, equivalent of up to third-degree relatives. For each related pair, this function removes whichever member has the highest number of relatives above the provided threshold, resulting in a maximal set.

CNV call set quality assessment

Mendelian violation rate from 935 trios

As the expected true de novo CNVs per generation should be less than 1 (ref. 57), the vast majority of CNVs inconsistent with Mendelian segregation in 935 parent–child trios must be either false-positive or false-negative CNVs in the child and/or parents. For each trio, we first annotated each CNVs into the following groups55 by overlapping child CNVs with both parent CNVs.

-

(1)

Inherited: CNVs had ≥ 50% overlap in length with a CNV of matching type (deletion or duplication) in at least one parent.

-

(2)

Apparent de novo: CNVs for which the child showed a heterozygous genotype and both parents were homozygous reference.

-

(3)

Spontaneous homozygote: CNVs for which the child was homozygous alternate and at least one parent was homozygous reference.

-

(4)

Untransmitted homozygote: CNVs for which the child was homozygous reference and at least one parent was homozygous alternate.

-

(5)

Untransmitted heterozygous: CNVs for which the child was homozygous reference and at least one parent was heterozygous alternate.

In these five groups, inherited and untransmitted heterozygous CNVs were not counted as Mendelian violations. For each trio, we computed the Mendelian violation rate as the fraction of all CNVs that were apparent de novo, spontaneous homozygote and untransmitted homozygote.

Comparison with NCBI-curated common CNVs

To evaluate how the UKB CNVs captured the known common CNV loci, we compared the variants with those documented in NCBI dbVar (nstd186). We required the variants with at least 50% overlap in length to be considered as found in both datasets. The results of the comparison showed that 91.5% of deletions and 99.0% of duplications in NCBI dbVar could be identified in UKB (Extended Data Fig. 2b). We further investigated the site frequency for these commonly identified CNVs. The correlation coefficients of the site frequency in the two datasets ranged from 0.79 to 0.87 across different ancestral groups, indicating good concordance for the common CNVs (Extended Data Fig. 2a).

Assessing Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

We selected 155 common CNVs found in 20,000 UKB participants to assess linkage disequilibrium concordance with nearby common variants genotyped using WGS24. We used PLINK58 to compute Hardy–Weinberg statistics for each CNV.

Linkage disequilibrium between SNV and CNVs

Using the 155 common CNVs mentioned above, we selected WGS SNV genotypes (minor allele frequency > 0.5%, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium P < 10−10, missingness < 1%) in a ±1-Mb window of each CNV for each of the 20,000 selected participants. We removed two CNV deletions (L:1-143539336–143751040 and L:2-90189440–90224075) for which there were fewer than 2,000 variants in the window selected and 28 with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium P < 10−10. For the remaining 125 CNVs, we used PLINK (–ld-snp <CNV> –r2 inter-chr –ld-window-r2 0) to compute the linkage disequilibrium between SNVs in the selected CNV window and the focal CNV. Results can be downloaded at our CGR platform (http://download.public.cgr.astrazeneca.com).

Assessment of sample size effects

To quantify the influence of sample size on detection of CNV frequency spectra, we subsampled the cohort across increasing sizes and compared observed frequencies for rare versus common variants. Rare CNVs showed an approximately linear, near-perfect correlation between observed frequency and cohort size, indicating strong sensitivity to sample size. By contrast, common variant frequencies stabilized and were largely unaffected once the cohort size exceeded 500 individuals.

CNV annotation

All CNVs that passed post hoc filtering were annotated against 19,347 protein-coding genes, 18,867 lncRNA genes and 1,880 miRNA genes from Ensembl 92. All genes, exons, untranslated regions (UTRs) from Ensembl 92 annotation were included in the analyses. If a gene had multiple transcripts, we included all transcripts in the analyses. UTRs were defined as the union of UTRs in all transcripts. Promoters were defined as the 1-kb window before the transcription start site. The predicted functional consequences of CNVs were defined as follows.

Protein-coding genes

-

(1)

LoF: a deletion overlaps with at least one exon of a gene or 50% of a gene.

-

(2)

Whole copy gain: a duplication spans a whole gene.

-

(3)

Exon duplication: a duplication spans at least one exon of a gene. Two breakpoints are in introns. Effect unknown.

-

(4)

Intragenic duplication: a duplication is in the gene and overlaps with exons. One breakpoint is in exon. Effect unknown.

-

(5)

Partial gene duplication: a duplication has partial overlap with a gene. One breakpoint is in the gene and the other outside the gene. Effect unknown.

-

(6)

Partial exon deletion: a deletion has partial overlap with a gene. One breakpoint is in the gene and the other outside the gene. Effect unknown.

-

(7)

Intraintronic deletion: a deletion is completely within an intron. Unlikely to have an effect.

-

(8)

Intraintronic duplication: a duplication is completely within an intron. Unlikely to have an effect.

-

(9)

UTR disruptive: a duplication or a deletion overlaps with a gene’s UTR regions but is not in any of the groups above.

-

(10)

Promoter disruptive: a duplication or a deletion overlaps with a gene’s promoter regions but was not in any of the groups above.

lncRNAs

-

(1)

LoF: a deletion overlaps with at least one exon of a gene or 50% of a gene.

-

(2)

Whole copy gain: a duplication spans a whole gene.

-

(3)

Exon duplication: a duplication overlaps with at least one exon of a gene. Two breakpoints are in introns. Effect unknown.

-

(4)

Intragenic duplication: a duplication is in the gene and overlaps with exons. One breakpoint is in exon. Effect unknown.

-

(5)

Partial gene duplication: a duplication has partial overlap with a gene. One breakpoint is in the gene and the other outside the gene. Effect unknown.

-

(6)

Partial exon deletion: a deletion has partial overlap with a gene. One breakpoint is in the gene and the other outside the gene. Effect unknown.

-

(7)

Intraintronic deletion: a deletion is completely within an intron. Unlikely to have an effect.

-

(8)

Intraintronic duplication: a duplication is completely within an intron. Unlikely to have an effect.

miRNAs

-

(1)

LoF: a deletion overlaps with at least one exon of a gene or 50% of a gene.

-

(2)

Whole copy gain: a duplication spans a whole gene.

-

(3)

Partial gene duplication: a duplication has partial overlap with a gene. One breakpoint is in the gene and the other outside a gene. Effect unknown.

-

(4)

Partial exon deletion: a deletion has partial overlap with a gene. One breakpoint is in the gene and the other outside a gene. Effect unknown.

Association analyses

CNV variant-level analyses

We tested 102,717 deletions and 80,147 duplications from 470,727 unrelated UKB genomes using Fisher’s exact two-sided test for binary traits and a linear regression (correcting for age, sex and age × sex) for quantitative traits, using our previously described framework3. We restricted the analysis to UKB samples of European ancestry using stringent genetic and self-reported criteria to ensure a highly homogeneous study population. Three distinct genetic models were used: deletion dominant, for which copy number = 1 or copy number = 0; deletion recessive, for which copy number = 0; and duplication dominant, for which copy number ≥ 3.

Some CNVs are multiallelic. We observed that 427 CNVs were multiallelic (Supplementary Fig. 16) in this study. We used a multiallelic model regressing protein level on CNV copy numbers (Supplementary Table 26). We then compared the results obtained with this model with those of simplified binary models (dominant and recessive) and found that binary models consistently showed greater power in detecting associations. For example, for the cis_1K pQTLs, binary models identified all associations found by the multiallelic model, and 12 further ones (Supplementary Fig. 17a). P values were largely comparable between the two approaches (Supplementary Fig. 17b). We found that binary models, by collapsing copy number states into two groups, simplified the analysis and increased power. Therefore, we reported binary models throughout the study.

For variant-level analysis, we used a significance cutoff of P < 10−8. Through performing an n-of-1 permutation on all variant-level PheWAS analysis, we obtained 2 false positives among 14,742 observed significant associations for binary traits (FDR = 0.01%) and 0 false positives among 5,933 observed significant associations for quantitative traits (FDR ≈ 0). We report associations with at least three CNV carriers and nine cases for binary traits, and with at least three CNV carriers for quantitative traits.

CNV gene-level collapsing analyses

Different CNVs can contribute to the same disease when they overlap with the same disease-associated genes. Among nearly 200,000 detected CNVs, approximately 75% deletions and 84% duplications overlapped with at least one protein-coding gene, miRNA gene or lncRNA gene (Supplementary Table 11). Notably, many genes were affected by several distinct CNVs: approximately 69% of protein-coding genes, 64% of lncRNA genes and 50% of miRNA genes were affected by more than two distinct CNV deletions. Similarly, about 92% of protein-coding genes, 89% of lncRNA genes and 87% of miRNA genes were affected by more than two distinct CNV duplications (Supplementary Table 12).

As several CNVs can overlap with a specific gene, aggregating these CNVs increases the site frequency of the gene-level event to boost statistical power. To illustrate this, we compared the site frequencies of individual CNVs with the site frequencies of genes after aggregation (for instance, duplication versus gene copy number gain; deletion versus gene copy number loss). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, the site frequency after aggregation of CNVs overlapping with a specific gene was higher than that obtained when studying each individual CNV. Similar to aggregating PTVs found across an index protein-coding gene, aggregating CNVs overlapping with an index protein-coding gene increased the number of carriers for that given gene and thus could enhance statistical power to detect gene–disease associations.

We created 15 CNV gene collapsing models using functional annotation of CNVs and site frequency as listed in Supplementary Table 27. Our gene-level collapsing models also considered CNVs in UTR and promoter regions. Deletions or duplications that intersect UTR or promoter regions of genes or duplications that partially overlap with genes may have unknown functional consequences. Most of these CNVs (96%) were correlated with decreases in levels of the affected protein (Fig. 3a), suggesting they had a LoF effect, and demonstrating the potential of this dataset to provide insight into the function of these regulatory regions.

Gene models that collapse rare CNVs tended to capture stronger associations with larger effect sizes, whereas models that also included more common CNVs generally showed smaller effect size associations (Supplementary Fig. 18).

In each model, for each gene, the proportion of cases was compared with the proportion of controls among individuals carrying CNV in that gene. For CNV gene-level analysis, we used a significance cutoff of P < 10−8. Through performing an n-of-1 permutation on all gene-level PheWAS analysis, we obtained 1 false positive among 17,056 observed significant associations for binary traits (FDR = 0.006%) and 5 false positives among 18,711 observed significant associations for quantitative traits (FDR = 0.027%).

PTV-augmented CNV gene-level analyses

Different types of variant could exert the same functional effect on genes, for instance, gene copy loss due to deletion and gene LoF due to PTVs. Notably, more than 14,000 genes were affected by at least one rare CNV deletion (site frequency < 0.001) and at least one rare PTV (allele frequency < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 19). On average, each individual carried 2.2 rare CNV deletions and 8.7 rare PTVs (Supplementary Fig. 19b). The average total number of LoF carriers per gene increased by 9% (P = 9.36 × 10−20) when both variant types were considered, compared with studying PTVs alone (Supplementary Fig. 19c). We sought to test whether more genotype–phenotype associations could be detected by integrating our small-variant standard PTV model3 with the CNV LoF_dom model. On the basis of functional annotation of CNVs and site frequency, we created 12 collapsing models as listed in Supplementary Table 27. For this assessment, only protein-coding genes with at least one qualifying PTV and at least one qualifying LoF CNV deletion in the cohort were included. For CNV + PTV gene-level analysis, we used a significance cutoff of P < 10−8. By performing an n-of-1 permutation on all gene-level PheWAS analysis, we obtained 18 false positives among 16,176 observed significant associations for binary traits (FDR = 0.1%) and 0 false positives among 17,266 observed significant associations for quantitative traits (FDR ≈ 0).

Pan-ancestry meta-analysis

For binary traits, we applied the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test to combine the results of PheWAS analysis across several ancestral groups. For quantitative traits, we used METAL59 to run meta-analysis of associations in genomic control.

We performed variant-level meta-analysis for three models: deletion dominant, deletion recessive and duplication dominant, involving six populations (NFE, ASJ, AFR, EAS, AMR and SAS). We performed gene-level meta-analysis for each of five categories (all the CNVs (CNV-all), CNVs with site frequency < 0.01 (CNV-sf001), CNVs with site frequency < 0.001 (CNV-sf0001), CNVs with site frequency < 0.01 with protein-truncating SNVs (CNV001-SNV), and CNVs with site frequency < 0.001 with protein-truncating SNVs (CNV0001-SNV)), involving five populations (NFE, ASJ, AFR, EAS and SAS). AMR was excluded from the analysis owing to a lack of carriers.

Population stratification assessment

To evaluate potential residual confounding by population structure beyond what had already been addressed by preanalysis ancestry harmonization, we reran the analyses for all 137 binary traits with statistically significant CNV associations, alongside a random sample of 100 binary traits that did not show statistically significant associations. For each of these 237 traits, we repeated CNV variant-level association testing using REGENIE (v.3.5), including age, sex and the first four ancestry principal components as covariates. Of the 237 phenotypes considered, five phenotypes had fewer than ten cases and were excluded from REGENIE analyses owing to limitations of regression models with respect to robust handling of sparse observations. The REGENIE results were highly concordant with those obtained using Fisher’s exact test (R2: 0.927–0.998; Supplementary Fig. 20). We also fitted a linear regression for height including four ancestry principal components. Inclusion of the four principal components yielded association statistics near-perfectly comparable with those of analyses without principal components (R2 = 0.999; Supplementary Fig. 21), indicating that our height associations were robust to population structure adjustment and that further principal-component-based ancestry control did not materially alter the conclusions.

Linkage disequilibrium analyses for suggestive CNVs (P < 10−6)

We performed linkage disequilibrium analyses for all CNVs with suggestive associations (P < 10−6) identified in the CNV variant-level PheWAS. To compare these CNV associations with known genetic signals, we obtained all genome-wide significant and suggestive SNP associations from the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog (accessed on 13 September 2024). We restricted this set to associations derived from individuals of European genetic ancestry and located within a ±1-Mb window of each suggestive CNV locus. To ensure consistency in genomic coordinates, we lifted over UKB genotyped variants from GRCh37 to GRCh38 using CrossMap. We then used PLINK v.1.9 (ref. 58) to compute pairwise linkage disequilibrium between each imputed SNP and the corresponding CNV. This approach enabled us to assess whether the CNV associations were potentially independent of or shared with nearby known GWAS SNPs.

Comparing trans-pQTL CNVs and SNVs

We used all significant associations (P < 1.7 × 10−11) from the combined cohort in the publication by Sun et al.22 to assess whether CNV-based trans-pQTLs were supported by any SNV-based pQTLs affecting the same protein and located within the corresponding CNV region. CNV trans-pQTLs were stratified into three significance groups (P < 10−8, 10−8 < P < 10−6 and P > 10−8) for common and rare variants separately. For each CNV–protein pair, we annotated the CNV pQTL as ‘with SNV pQTL support’ if a significant (P < 1.7 × 10−11) SNV-based pQTL for the same protein was present within the CNV interval. We then compared (1) the proportion of CNV trans-pQTLs with supporting SNV pQTLs across the three significance groups and (2) the effect sizes of CNV-based and SNV-based pQTLs. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6a, CNVs with stronger trans-pQTL signals (P < 10−8) were significantly more likely to overlap with SNV pQTLs for the same protein than less significant CNVs, in both common and rare variant groups. Likewise, the 10−8 < P < 10−6 group had more supporting SNV pQTLs than the P > 10−6 group (Supplementary Fig. 6b).

Effects of blood cell composition

We reanalysed the associations for the eight trans-pQTLs using Olink data (at the variant level) after adjusting for an extensive range of blood cell covariates, including counts of white and red blood cells, platelets, lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils and reticulocytes, as well as haemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular volume and mean sphered cell volume. Before analysis, individuals with extreme blood cell measurements were excluded, as described previously22. After these exclusions and quality control steps, we repeated the genetic association analyses of the variant–protein pairs, adjusting for blood cell covariates and applying the analytical framework used in the main analysis. We found that blood cell composition had a limited impact on most of the trans-pQTL effects and protein variances, consistent with the findings of previous studies (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Table 28).

Unified study-wide significance cutoff

We chose to apply a single, study-wide significance threshold (P < 10−8) across all analyses rather than tailoring P value cutoffs to each specific test or dataset, following a rationale established in previous work3. This approach was chosen to ensure consistency in interpretation and to maintain a conservative overall false-positive rate. The FDR range for a P value threshold of 10−8 was found to be 0–0.1%. However, we have also provided all summary statistics as a separate file to enable readers to explore signals for all P value ranges.

Reported genomic disorder regions

To identify new genomic dosage-sensitive regions associated with diseases and traits, we integrated regions of genomic disorder reported in six published resources12,16,27,28,29,30. We selected these representative studies and databases because they are widely cited and provide curated CNV–trait associations relevant to both clinical and population-based contexts. However, we acknowledge that these resources do not capture the full breadth of the published CNV literature. We downloaded ClinVar pathogenic CNV BED file from NCBI dbVar28 and selected only variants classified as ‘copy number gain’ or ‘copy number loss’ with a germline origin and with length greater than 10 kb. In addition, we obtained a list of CNVs associated with 66 expert-curated microdeletion and microduplication syndromes involved in developmental disorders from DECIPHER27. We then manually curated CNVs involved in significant associations into three groups:

-

(1)

reported (same phenotype), if a CNV had 50% or more reciprocal overlap in variant length with previously published CNVs associated with the same phenotype;

-

(2)

reported (different phenotype), if a CNV had 50% or more reciprocal overlap in variant length with previously published CNVs but was associated with a different phenotype in our dataset;

-

(3)

unreported, if a CNV did not have 50% or more reciprocal overlap in variant length with any of the examined previously published CNVs.

Assessment of genomic inflation factor λ

Genomic inflation factor λ was computed using an n-of-1 permutation approach for (1) the Olink, (2) the CNV quantitative traits and (3) the CNV binary traits (Supplementary Fig. 23). The n-of-1 permutation is a method used in PheWASs to assess the significance of associations by randomly shuffling phenotype labels (for instance, disease status or quantitative trait values) across individuals while keeping genotypes intact. This generates a phenome-wide null distribution of P values, reflecting results expected by chance. On the basis of the permutation results, we calculated the FDR for different models using differing P value thresholds, as shown in Supplementary Table 29. The range of FDR for our conservative study-wide significance P value threshold of 1 × 10−8 was found to be 0–0.1%, whereas for our chosen suggestive P value of 1 × 10−6, the FDR range was 0.4–1.8%. For Olink analysis, the median λ was 1.02 for CNV gene-level collapsing analysis, 1.02 for CNV + PTV gene-level collapsing analyses and 1.02 for variant-level analysis. For CNV quantitative traits, the median λ was 1.03 for CNV gene-level collapsing analysis, 1.04 for CNV + PTV gene-level collapsing analyses and 1.02 for variant-level analyses. For CNV binary traits, the median λ was 1.01 for CNV gene-level collapsing analysis, 1.01 for CNV + PTV gene-level collapsing analyses and 1.00 for variant-level analysis. Of the associations, 99.9% were within the 0.9–1.1 λ range for the Olink CNV gene-level collapsing analysis, 92.1% for the Olink CNV + PTV gene-level collapsing analysis and 99.7% for the Olink variant-level analysis. For CNV quantitative traits, 81.8% (CNV gene-level) and 90.9% (CNV + PTV gene-level) of the quantitative associations were within a 0.9–1.1 λ range for the collapsing analysis and 95% for the variant-level analysis. For binary traits, 40.4% (CNV gene-level) and 90.2% (CNV + PTV gene-level) of the binary associations were within a 0.9–1.1 λ range for the collapsing analysis and 72.5% for the variant-level analysis. Our tests were thus highly robust to systematic bias and other sources of inflation. The λ values for different models are provided in Supplementary Table 30.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.