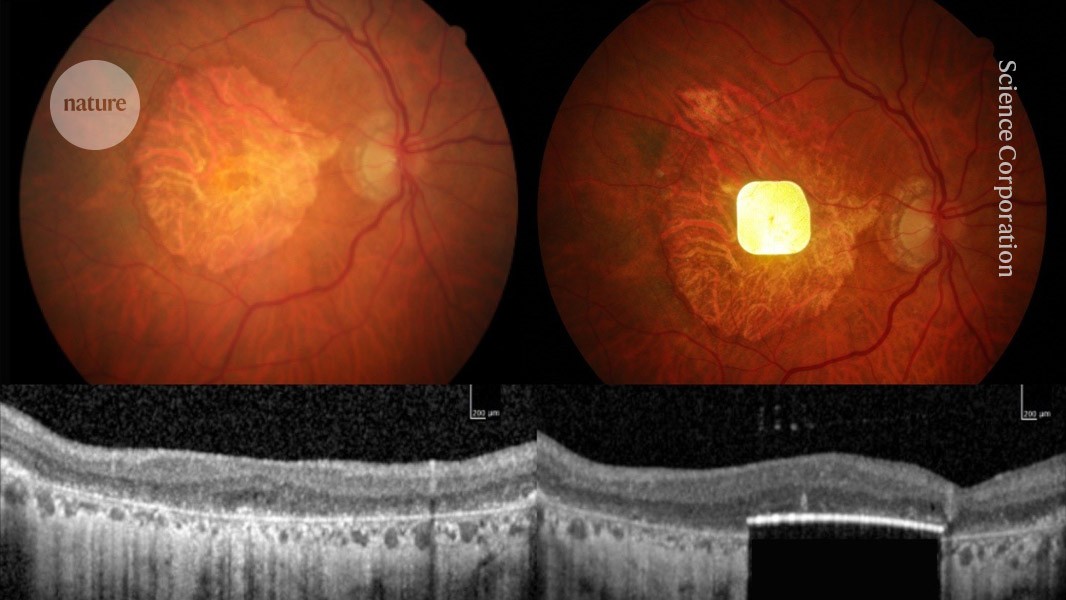

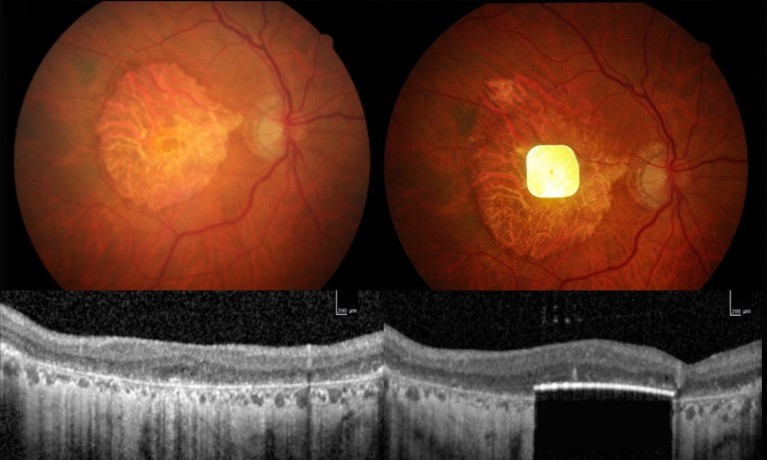

An electrical device implanted under the retina helps to restore some visual acuity to people with age-related macular degeneration.Credit: Science Corporation

Scientists have used an eye implant to improve the vision of dozens of people left functionally blind by age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The implant, which measures 2 millimetres by 2 millimetres, and is just 30 micrometres thick, is surgically inserted beneath the retina to replace the light-sensitive cells that have been lost to the disease.

The clinical trial, which is described today in The New England Journal of Medicine1, involved 38 people with advanced AMD whose retinas had degenerated severely. One year after device implantation, 80% of participants had gained a clinically meaningful improvement in their vision.

“Where this dead retina was a complete blind spot, vision was restored,” says trial leader Frank Holz, an ophthalmologist at the University of Bonn in Germany. “Patients could read letters, they could read words, and they could function in their daily life.”

Reversing blindness with stem cells

Despite some minor events related to implantation surgery, the trial’s safety-monitoring board viewed the device’s benefits as outweighing its risks. In June, the device’s owners — the San Francisco-based neurotechnology company Science Corporation — applied for certification that would allow the device to be sold on the European market.

“I think this is an exciting and significant study, which has been well-designed and analysed. It gives hope for providing vision in patients for whom this was more ‘science-fiction’ than reality,” says Francesca Cordeiro, an ophthalmologist at Imperial College London.

Restored vision

AMD is the commonest form of incurable blindness in older people. There are two main types, wet and dry AMD. The current work studied people with dry AMD, the advanced form of which affects around 5 million people globally. In dry AMD, the central retina’s light-sensitive cells die over a period of years, leaving affected individuals with intact peripheral vision but without their high-acuity central vision. “They can’t recognize faces, they can’t read, they can’t drive a car, they can’t watch television,” says Holz.

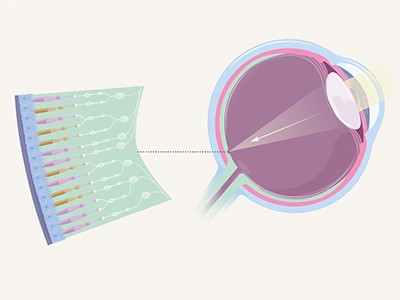

The light-sensitive cells that die (rods and cones) convert light into electrochemical signals that are conveyed to other types of retinal neurons, which then send messages to the brain’s visual-processing regions. Because retinal neurons survive AMD, scientists reasoned that a light-sensitive implant that electrically stimulates the retina according to the pattern of photons striking it could reinstate a sense of vision.

A visual guide to repairing the retina

The implant, termed PRIMA — for photovoltaic retina implant microarray — was originally developed by the Paris-based company Pixium Vision, and was acquired by Science Corporation last year. It is wireless, unlike previous retinal devices. And, being photovoltaic, the photons that activate it also provide the energy source for generating its electrical output.

It is used in combination with glasses that contain a camera that captures images and converts them into patterns of infrared light that they transmit to the retinal implant.

The system, which allows users to zoom in and out on target objects, and adjust contrast and brightness, does, Holz says, take months of intensive training to use optimally.

In the current study, 38 individuals were treated at 17 clinical sites across 5 European countries, and 32 of the participants were tested a year after implantation. Twenty-six of them had a clinically meaningful improvement in their vision — which, on average, amounted to being able to see two lines further down a standard eye test chart of letters. Overall, most participants’ vision came close to the resolution achievable with PRIMA.

By the study’s end, most recipients were using PRIMA at home to read letters, words and numbers. Of the 32, 22 said that their user satisfaction was medium to high.