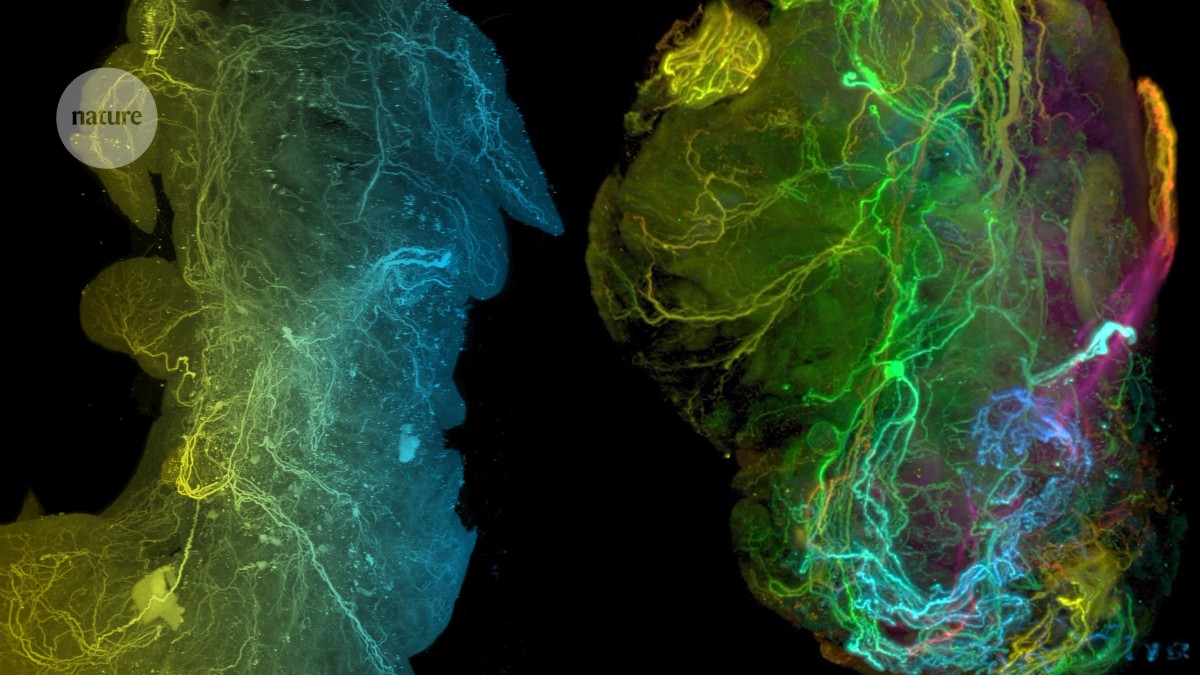

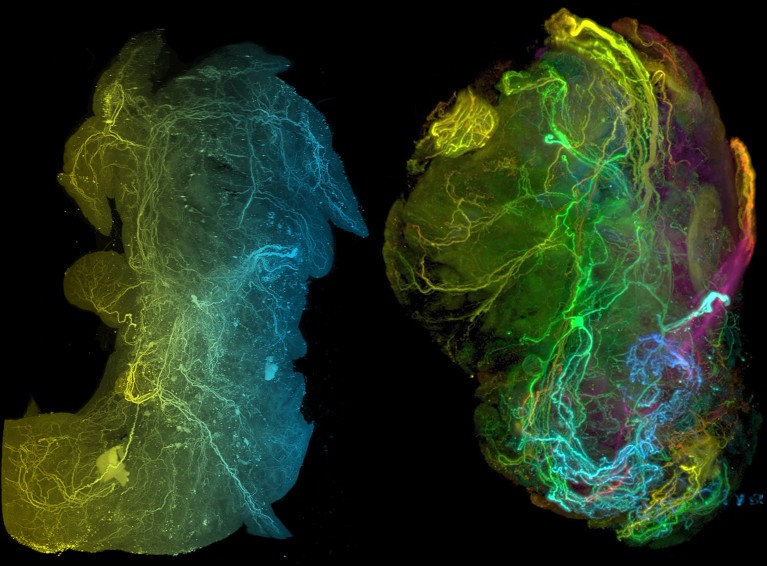

The neural network in a healthy pancreas (left) and in a pancreatic tumour (right).Credit: Ref. 4

When Jami Saloman gave capsaicin, the molecule that gives peppers their signature spice, to newborn mice in 2015, she expected that it would ease the pain of the pancreatic tumours that the mice were bred to develop.

The mice had a mutation that is present in 90% of people with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most lethal form of the cancer. Typically, these mice develop precancerous lesions by eight weeks of age and survive little more than a year. Saloman, who at the time was a postdoctoral researcher studying pain, knew that high doses of capsaicin blocked sensory nerve signals, and, therefore, might block the pain of the cancer in mice.

Nature Outlook: Pancreatic cancer

Surprisingly, it seemed to do much more than that. None of the mice given capsaicin developed pancreatic cancer, even after nearly 19 months1. “We were really shocked,” says Saloman, who is now a neurobiologist at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. And “it completely changed the trajectory of my career”, she says.

Saloman had stumbled into the field of cancer neuroscience, in which researchers were just beginning to investigate the relationship between cancer and the nervous system. Instead of studying pain, she opened a lab investigating what sensory nerves do in the spaces in which cancers grow, known as the tumour microenvironment.

A decade later, she and other researchers have gained some understanding of how cancers use the body’s nervous system to survive, grow and spread. Pancreatic cancer is particularly good at it: cancer cells spread into the nervous system in nearly everyone with the disease. In colon cancer, by comparison, around 30% of people show signs of such neural invasion. Pancreatic cancer cells also overexpress genes with neuronal functions, influence communication between nerves and the immune system, and take amino acids from neurons. Without the nervous system, it seems, pancreatic cancer would be an entirely different, and probably less deadly, disease.

Currently, only around 13% of people with pancreatic cancer survive for five years after diagnosis, says Elizabeth Jaffee, co-director of the Skip Viragh Center for Pancreas Cancer Clinical Research and Patient Care at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. But a growing understanding of the tumour microenvironment and the involvement of neurons could provide an opportunity to improve that, she says. “This is going to lead to new therapies.”

Cancer-nerve connections

The first descriptions of neural invasion in people with cancer date back more than a century. But it took the arrival of modern technologies, such as single-cell RNA sequencing, genetic mouse models and the ability to isolate neurons, to gain a fuller view of cancer’s ability to not only invade nerves but also to attract them.

Researchers now know, for instance, that even before the cancer is malignant, it begins releasing proteins called nerve growth factors. These attract parts of the peripheral nervous system that connect nerves around the body to the brain and spinal cord. Scientists have also found that pancreatic cancer cells cling to nerve cells and dot the spinal cord at very early stages of the disease — much earlier than it would typically be said to have spread beyond the pancreas, Saloman says.

Cancer cells even form connections with nerve cells that are similar to the synapses that neurons use to talk to each other, researchers have reported2. These pseudo-synapses provide a neurotransmitter, called glutamate, that helps the cancer to grow; mice given a drug that blocks a receptor for that transmitter survived longer with pancreatic cancer. “We now have a nervous-system-derived target, a really good target,” says Ekin Demir, head of pancreatic surgery at the Technical University of Munich in Germany, who contributed to the discovery of nerve growth-factor release.

That aligns with previous findings showing that PDAC keeps itself functioning by calling on neurons. For example, a 2020 study3 that analysed human PDAC cells found that some could not produce the amino acid serine, which tumours need for metabolism and survival. But when those cells are cultured in dishes with serine-producing axons from rats, they thrive. By releasing nerve growth factors and axonal guidance molecules, PDAC tumours can ensure that their environment is densely packed with serine-producing axons, says Vera Thiel, a cancer researcher at the German Cancer Research Center (DFKZ) in Heidelberg.

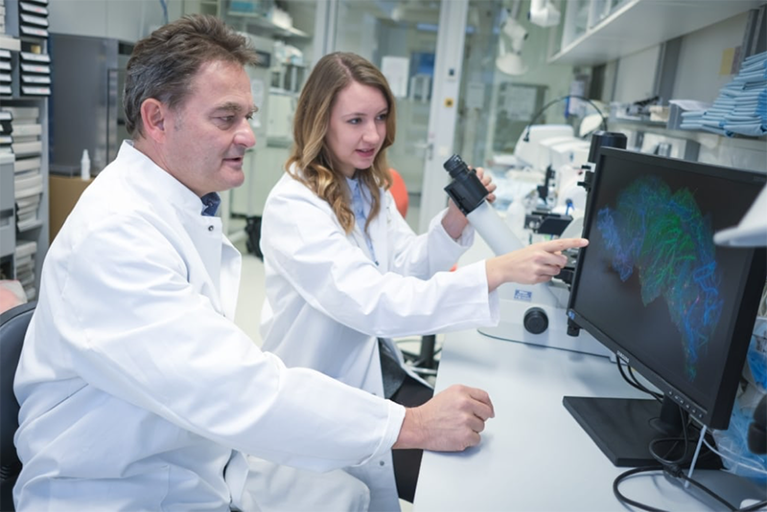

Vera Thiel (right) and her team have sequenced thousands of neurons from tumours. Credit: ©Carina C. Kircher/www.carinakircher.de

The cell bodies of those tumour-supplying nerves lie outside the pancreas, however, making it difficult for researchers to know which neurons are supporting the cancer. To find out, Thiel developed a method called Trace-n-Seq, in which a blue tracer is injected into an organ or tumour, and travels along the axons and back to the nerve cell’s nucleus. This allows researchers to sequence genes that are expressed only by those neurons that populate the tumour.

Thiel and her colleagues have now sequenced 4,000 neurons from tumours and healthy pancreatic tissue. They found that neurons connected to cancer cells have different gene-expression profiles4 from those of healthy mice — suggesting that the cancer is reprogramming the neurons.

Recruiting reinforcements

As well as attaching to nerves and tinkering with their gene activity, it turns out that pancreatic cancer also co-opts some survival skills that neurons use — a phenomenon that was stumbled upon by cancer biologist Sohail Tavazoie at Rockefeller University in New York City.

When Tavazoie started a residency in internal medicine in 2001, he thought he was leaving behind his doctorate in neuroscience for good. Watching his patients die of metastatic cancer, left him devastated, and so he devoted himself to understanding the genes that drive tumour spread. This is when neuroscience made a reappearance. While investigating colorectal cancer cells, Tavazoie spotted that metastasizing tumour cells overexpress5 a gene called CKB. He knew that this gene helped brain cells to survive a lack of oxygen, or hypoxia, which is common inside tumours.

In work published6 last year, Tavazoie selectively grew pancreatic cancer cell lines that were particularly good at colonizing the liver (metastasis to the liver is especially deadly). He found that these cells overexpress a different gene, called NPTX1, that makes neurons more resilient to hypoxia. “I cannot leave neuro. It comes back and haunts me,” Tavazoie says.

Pancreatic cancer’s connection with the nervous system extends beyond hypoxia, researchers are finding out. This type of cancer might also mimic the strategies that nerve cells use to protect themselves against the damage that the immune system sometimes inflicts while fighting infections and foreign invaders.

This could also help to explain why immunotherapy — when the immune system is activated against tumour cells — is often unsuccessful for pancreatic cancer.

After Saloman’s colleague at the University of Pittsburgh, Brian Davis, presented the capsaicin data at a conference in 2016, he was asked whether sensory neurons express checkpoint proteins. These proteins suppress immune activity and form the basis of cancer immunotherapy, but, at the time, they weren’t on Davis’s radar.

“We start looking and holy, they do! They really do,” Davis says. The finding meant that sensory neurons have a mechanism for suppressing the immune system and protecting themselves and, in turn, any connected cancer cells, he says. It’s a theory that he, Saloman, and another colleague called the ‘safe harbour hypothesis’. It’s yet another example of cancer’s ability to use nerves to co-opt other systems for its own survival, Davis says: “It takes a village to make a cancer.”

Other groups have similarly found, for example, that pancreatic cancer cells communicate with pain neurons through nerve growth factors7 to prevent immune cells from infiltrating cancer cells. People with PDAC whose cancer cells had higher levels of a neuropeptide known for its role in migraines had fewer of a type of immune cell that kills diseased cells — including, usually, cancerous ones — a higher likelihood of relapse and more pain than did people whose cells had lower levels of the protein.

To make sense of it all, researchers will need to understand how the nervous system helps healthy tissue to grow, Demir says — and how pancreatic cancer uses those mechanisms. “It is time to go deeper into that direction,” Demir says. “There, the possibilities might be endless.”

Translating to treatment

The amount of crosstalk between cancer and the nervous and immune systems is prompting researchers to think about intersecting disciplines. Cancer neuroscience, Davis says, “is a mess because you have neuroscience guys who don’t know much about cancer, you have cancer guys who don’t know anything about neuroscience, and you have immunologists who know nothing about both”.

Even so, researchers are thinking about ways to leverage what they do know for therapies. It seems unlikely that targeting nerves by themselves will do much to move the needle, Jafee says. Chemotherapy can already cause debilitating nerve damage in people with pancreatic cancer, and yet their cancer persists. But combinations of therapies, such as those that target nerves, could make a difference.

In mice, for example, the immunotherapy drug nivolumab alone does not shrink pancreatic tumours. But when Thiel and her colleagues combined the cancer treatment with a neurotoxin called 6-hydroxydopamine, which kills neurons, tumour size fell nearly sixfold6. This is probably because, without signals from nerves, the immune cells could once again enter the tumour. The researchers are now planning a clinical trial that will pair nerve-killing radiation with immunotherapy drugs.

For many oncologists, this is the ultimate promise of targeting the nervous system. “You’re still going to need those other interventions and therapies,” Saloman says. “What we can do is leverage the nervous system to improve the efficacy of those other therapies.”