mEosEM fusion proteins

New plasmids were submitted to Addgene, and their construction is described in the history of the linked SnapGene files. Plasmid pET28a–Imp β1–mEosEM encoding Imp β1–mEosEM with a C-terminal 6×His tag was created by attaching mEosEM to the C terminus of human Imp β1. The gene encoding Imp β1 was from pQE9-β1 (ref. 49) and the gene encoding mEosEM was from pRSET-mEosEM25. Plasmid pTrcHisA–NLS–BFP–mEosEM encoding NLS–BFP–mEosEM with a C-terminal 6×His tag was created by replacing the C-terminal blue fluorescent protein (BFP) domain in the import cargo NLS–2×BFP7 with mEosEM25. Coding sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

Protein overproduction and purification

Protein overproduction and purification protocols are provided in the following sections or the indicated references. When used, antibiotics were 50 µg ml−1 for ampicillin (Amp) and 30 µg ml−1 for kanamycin (Kan). All purified proteins were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use.

LaG-9(S151C), Imp α, Imp β, NLS–2×BFP, RanGDP and NTF2

These proteins were overproduced in Escherichia coli and purified as previously described7. Plasmids pET21b–LaG9(S151C) and pNLS–2×BFP are available from Addgene (ID#172490 and ID#176151, respectively).

GST–CAS

The plasmid pGEX4T3–CAS50 encodes GST fused to the N terminus of CAS (GST–CAS). JM109 cells51 transformed with pGEX4T3–CAS were inoculated into 5 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) medium52 + Amp, and then were incubated overnight at 30 °C. The following day, the starter culture was transferred to 0.5 l LB + 1% glucose + Amp and incubated at 30 °C. At an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 2, 2 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added, and the culture was incubated for another 2 h at 30 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (at 5,000g for 10 min at 4 °C). The cell pellet was resuspended in 1.5 ml of 10× PBS (1.37 M NaCl, 27 mM KCl, 100 mM Na2HPO4 and 18 mM KH2PO4) and 13.5 ml of H2O, and then 5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme were added. Cells were lysed by French Press (three times at 16,000 psi). The lysate was centrifuged (at 10,000g for 15 min at 4 °C) and the supernatant was mixed with 0.6 ml of glutathione Sepharose beads (#GE17-0756-01, Millipore Sigma) that had been equilibrated with ice cold PBS. After rotary incubation (for 3 h at 4 °C), the suspension was transferred to a gravity column, and the resin was washed with 10 ml of PBS + 0.1 mM PMSF, 10 ml of PBS + 600 mM NaCl, and then 10 ml of PBS + 0.1 mM PMSF. The protein was eluted (1-ml fractions) with ice-cold 100 mM Tris-Cl, 120 mM NaCl and 20 mM reduced glutathione, pH 8.

RanGAP and RanBP1

Plasmids pQE60–RanGAP and pQE60–RanBP1 (gifts from D. Görlich)49 were used to overproduce Schizosaccharomyces pombe RanGAP and mouse RanBP1, respectively, in JM109. The proteins had a C-terminal 6×His-tag and were purified identically. Cells were inoculated into 5 ml LB + Amp, and then were incubated overnight at 37 °C. The following day, the starter culture was transferred to 1 l LB + Amp and incubated at 37 °C. At an OD600 of approximately 0.8, 1 mM IPTG was added, and the culture was incubated overnight at 25 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (at 5,000g for 20 min at 4 °C). The cell pellet was resuspended in 20 ml of 5 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM imidazole, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol (βME), pH 7.0, + protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 100 µg ml−1 trypsin inhibitor, 20 µg ml−1 leupeptin and 100 µg ml−1 pepstatin A), and then lysed by French Press (three times at 16,000 psi). The lysate was centrifuged (15,000g for 20 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was mixed with 0.5 ml Ni-NTA resin (rotated for 30 min at 4 °C). The suspension was transferred to a gravity column, and the resin was washed with 20 ml of 5 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.0, + protease inhibitor and then 20 ml of 5 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8. The protein was eluted (1-ml fractions) with 5 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 250 mM imidazole, pH 8. The protein in the highest concentration fraction was purified by Enrich SEC 650 (7801650, Bio-Rad) size-exclusion chromatography using 20 mM HEPES, 110 mM potassium acetate (KOAc), 5 mM sodium acetate (NaOAc), 2 mM magnesium acetate (MgOAc2) and 2 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.4.

Imp β1–mEosEM

BL21(DE3) cells53 transformed with plasmid pET28a–Imp β1–mEosEM were inoculated into 5 ml LB supplemented with 2% glucose + Kan, and then were incubated overnight at 37 °C. The following day, the starter culture was transferred to 1 l of LB medium with 2% glucose and Kan and incubated at 37 °C. At an OD of approximately 0.8, 0.7 mM IPTG was added, and the culture was incubated for another 3 h at 37 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (at 5,000g for 10 min at 4 °C). The cell pellet was resuspended in 6 ml of 5 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgSO4, 10 mM imidazole, 4 mM βME, pH 8.0, + protease inhibitors and then lysed by French Press (three times at 16,000 psi). The lysate was centrifuged (at 15,000g for 20 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was mixed with 0.5 ml Ni-NTA resin (rotated for 30 min at 4 °C). The suspension was transferred to a gravity column, and the resin was washed with 20 ml of 5 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgSO4, 10 mM imidazole, 4 mM βME, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.0, + protease inhibitors and then 20 ml of 5 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole, pH 8. The protein was eluted (500-µl fractions) using 5 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0. The highest concentration fractions were combined, and the protein was purified by Enrich SEC 300 size-exclusion chromatography using 20 mM HEPES, 110 mM KOAc, 5 mM NaOAc, 2 mM MgOAc2 and 2 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.4.

NLS–BFP–mEosEM

JM109 cells51 transformed with plasmid pTrcHisA–NLS–BFP–mEosEM–6×His were inoculated into 5 ml LB + Amp, and then were incubated overnight at 37 °C. The following day, the starter culture was transferred to 1 l LB + Amp and incubated at 37 °C. At an OD of approximately 0.8, 0.7 mM IPTG was added, and the culture was incubated for 14 h at 25 °C. The remainder of the protein purification protocol was identical to that for Imp β1–mEosEM.

Protein labelling

The spontaneously blinking dye HMSiR maleimide (SaraFluor 650B-maleimide; A209-01, Goryo Chemical) was attached to the C-terminal cysteine on the anti-GFP nanobody LaG-9(S151C) by incubating with a 15-fold molar excess at room temperature for 15 min to yield NbGFP–HMSiR. Imp α was under labelled with JF549 maleimide (Janelia Fluor 549 maleimide; 6500, Tocris) by incubating with a 10-fold molar excess at room temperature for 15 min in 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 (maximum reaction volume of 1 ml) to yield Imp α–JF549. On the basis of the concentration-dependent labelling efficiency, this molar excess produced approximately 25% labelling saturation (approximately 1 cysteine labelled, on average, out of the 4 available reactive cysteines). The reactions were quenched with 10 mM βME. Excess dye was removed by adding the dye–protein mixture to 0.1 ml Ni-NTA resin (30-min incubation), washing the resin-bound protein with 50 ml of 20 mM HEPES, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.3, and 20 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.3, and then eluting the labelled proteins with 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole, pH 7.3.

Protein concentrations and labelling purity

Protein concentrations were determined by densitometry using SDS–PAGE gels stained with Coomassie Blue R-250 with bovine serum albumin as a standard and a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The purity of dye-labelled proteins was more than 95%, as determined by in‐gel fluorescence imaging using the same ChemiDoc imaging system.

Cell culture

For MINFLUX imaging, U2OS-CRISPR–NUP96–mEGFP clone #195 (300174, CLS GmbH) cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (11880028, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 1× MEM non-essential amino acids solution (11140050, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× GlutaMAX solution (35050061, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× ZellShield (13-0050, Minerva Biolabs) and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (F7524, Sigma) in 5% (v/v) CO2 enriched air at 37 °C. Cells were typically grown to approximately 80% confluency and split using TrypLE Express (12604013, Thermo Fisher Scientific) without phenol red.

For 3D astigmatism and Luminosa confocal imaging, U2OS-CRISPR–NUP96–mEGFP clone #195 and U2OS (300364, CLS GmbH) cells were grown in McCoy’s 5A (modified) media (16600082, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin (15140148, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360070, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× MEM non-essential amino acids solution (11140050, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (A3160401, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 5% (v/v) CO2 enriched air at 37 °C. Cells were typically grown to approximately 95% confluency and were split using Accutase (A1110501, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were grown from fresh stocks and used within 1 month; they were not tested for mycoplasma contamination or authenticated.

3D MINFLUX imaging

Microscope system

A MINFLUX 3D microscope (Abberior Instruments) was used for all MINFLUX localization and tracking experiments. A 100× oil immersion objective lens (UPL SAPO100XO/1.4, Olympus) and 488-nm, 561-nm and 642-nm CW excitation lasers were used for mEGFP confocal imaging, cargo tracking and NPC scaffold localization, respectively. Four avalanche photodiodes (SPCM-AQRH-13, Excelitas Technologies) with detection ranges of 500–550 nm, 580–630 nm, 650–685 nm and 685–760 nm were used with a pinhole size corresponding to 0.78 airy units. All hardware was controlled by Abberior Imspector software (v16.3.13924-m2112). Drift during tracking was minimized using the built-in stabilization system with typical drifts less than 1 nm in xyz. Scattering from 200 nm gold nanoparticles (A11−200-CIT-DIH-1-10, Nanopartz) pre-deposited on the coverslip surface and at a similar z height to the bottom of the nucleus were used as a positional reference for the sample stabilization and two-colour alignment registration.

Sample preparation

Six channel μ-Slide VI 0.5 glass bottom slides (80607, Ibidi) were pre-treated with 200 nm gold nanoparticles (used as a positional references) and poly-l-lysine (which reduced cell-detachment after permeabilization). Undiluted 200 nm gold nanoparticles (A11-200-CIT-DIH-1-10, Nanopartz) were added to each channel, and 15 min later were washed away with 1× PBS. Then, 50 µl of 0.01% poly-l-lysine (P4832, Sigma) was added to each lane. After 5 min, the lanes were washed with cell culture media (3 × 100 µl). Freshly split U2OS NUP96–mEGFP cells (to less than 60% confluence) were grown overnight on the pre-treated coverslips. The next day, the cells were washed with 50 µl of import buffer (20 mM HEPES, 110 mM KOAc, 5 mM NaOAc, 2 mM MgOAc2 and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.3) and then permeabilized by the addition of 2 × 50 µl of 40 µg ml−1 digitonin in import buffer for 3 min. Permeabilized cells were washed once with 50 µl import buffer–polyvinylpyrrolidone (IB–PVP; import buffer containing 1.2% (w/v) PVP (360,000 g mol−1; P5288, Sigma)). This permeabilization method was slightly modified from Yang et al.26 to accommodate the different cell line and growth conditions. NbGFP–HMSiR in IB–PVP (40 µl, 150 nM) was incubated with the permeabilized cells for 6 min. The cells were washed twice (2 × 40 µl IB–PVP). ‘Transport mix’ (40 µl), consisting of 1.5 µM RanGDP, 1.5 µM NTF2, 1.0 µM RanGAP, 1.0 µM RanBP1, 1 mM GTP, 0.5 µM Imp β1, 0.5 µM NLS–2×BFP, 2 µM GST–CAS and 1 nM Imp α–JF549 in IB–PVP was added to the permeabilized nanobody-tagged cells, and MINFLUX imaging begun approximately 1 min after addition.

Imaging and tracking

A diagonal scanning approach with a grid spacing of 300 nm was used to find both fluorophores, and then an iterative strategy within z = 0 ± 400 nm was used to localize HMSiR on the NPC scaffold or to track Imp α–JF549 in 3D. Non-default measurement parameters for the individual MINFLUX scan iterations are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 3. The pooled results reported here were acquired using slightly different measurement parameters to optimize signal acquisition over background contributions. The data obtained via these distinct imaging conditions are identified as datasets 1 and 2 (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 3). Approximately 15–20 min was used for NbGFP–HMSiR localizations, and approximately 15–20 min was used for tracking cargo transport. Confocal images of the mEGFP fluorescence (excitation = 488 nm) from NUP96–mEGFP in the region of interest were obtained at the beginning and end of MINFLUX imaging.

Channel alignment

Coordinates were transformed from the JF549 emission channel to the HMSiR emission channel, which was the reference. The xyz coordinates from the same 8–10 gold nanoparticles (200 nm) on each cell were measured every few seconds during the two independently recorded MINFLUX datasets (HMSiR imaging and cargo tracking). During post-processing, the gold nanoparticle coordinates from the two datasets were used to derive an xy alignment matrix incorporating rotational and translational corrections, as described earlier7, which was used to transform the JF549 coordinates to the HMSiR coordinate system with a precision of approximately 2 nm. A correction factor of 0.67 as determined in Extended Data Fig. 4 was applied to all z values. The mean z position for the gold nanoparticles associated with each cell differed by 5–14 nm between the two channels, and the z coordinate was corrected by simple subtraction of this mean z deviation.

Data filtering parameters

Multiple parameters providing information about the photons collected in the MINFLUX scan patterns were used for data filtering. These are reported as frequencies (in kHz) or ratios. The frequencies are discrete variables, as they were obtained by dividing the number of photons collected (that is, a quantized variable) during a collection period:

Effective frequency at centre

The effective frequency at centre (EFC) is the emission frequency measured at the centre of the MINFLUX scan pattern.

Effective frequency at offset

The effective frequency at offset (EFO) is the averaged emission frequency measured over all points in the xy plane of the MINFLUX scan pattern except for the centre.

Centre frequency ratio

The centre frequency ratio (CFR) is the ratio of the EFC and EFO, that is, CFR = EFC/EFO. The CFR is a measure of the quality of a localization. As the fewest photons are collected when the centre of the excitation donut coincides with the fluorophore position, a high CFR can indicate that the centre of the scan pattern is not well localized to the position of the fluorophore or that a second fluorophore is close by. Thus, lower CFR values indicate good localizations.

Detector channel ratio

The detector channel ratio (DCR) is the fractional component of photons collected in one of two channels. It is used to distinguish fluorophores with different emission spectra present within the same sample, and it can be effective for eliminating some background signals. For example, if detector channel 1 collects an emission frequency in the 650- to 685-nm range (EF1), and detector channel 2 collects an emission frequency in the 580- to 630-nm range (EF2), the detector channel ratio = EF1/(EF1 + EF2).

Identifying NPC scaffolds from HMSiR localizations

3D HMSiR localizations were obtained using an eight iteration MINFLUX sequence (Supplementary Table 1). Iterations 1–6 were used first to locate the molecule and then for progressively increased localization precision. The final output coordinates came from iteration 7 (xy) and iteration 8 (z). The CFR upper limit was set to 0.8 (see Extended Data Fig. 6a) and was checked within iteration 7. This CFR check occurred at the level of data acquisition to help eliminate acquisitions where two nearby HMSiR molecules were simultaneously in the ‘on’ state. Successive localizations occurred by cycling between iterations 7 and 8 until the CFR check failed, or the fluorophore switched off for longer than 3 ms. To distinguish HMSiR localizations from background noise, an EFO lower limit of 25 kHz or 50 kHz (for datasets 1 and 2, respectively) was used during acquisition. An upper EFO threshold of 60 kHz or 100 kHz (for datasets 1 and 2, respectively) was used post-acquisition to eliminate signals from multiple dye molecules that were not eliminated by the CFR check during acquisition (see Extended Data Fig. 6b). HMSiR localizations were exported using ‘MINFLUX-BASE Imspector 16.3.15620’ and Paraview 5.8.1 software.

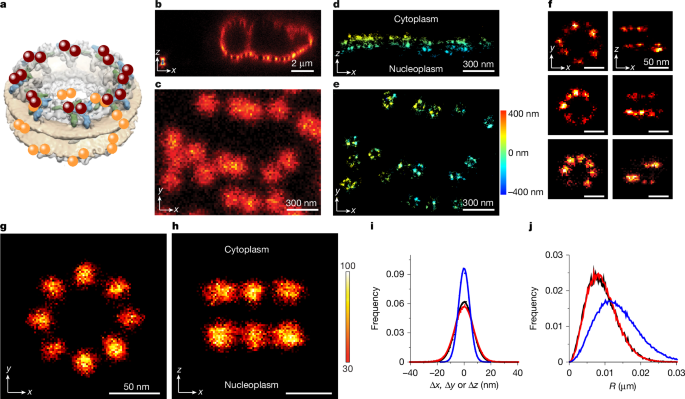

Individual NPCs were identified, and averaged NPC scaffolds were generated essentially as done previously using localizations from astigmatism imaging7. This approach is briefly outlined here and in Extended Data Fig. 3. The localizations in each of the individual NPC localization clusters were fit to a double-circle model, which reflected the double-ring structure of NUP96 within the NPC (Fig. 1a). Owing to the relatively flat nuclear envelope, we assumed that the two circles were both parallel to the xy plane with their centres defining an axis parallel to the z axis. Although the nuclear envelope was not perfectly flat (for example, Fig. 1d), the angular tilt of the NPCs used was less than 10°, consistent with our previous analysis7. The angles of the individual localizations relative to the centroid obtained from the double-circle fit for each NPC were binned (0–45°), assuming an eightfold periodicity, and fit to a sinusoidal function with a 45° period and a variable phase. The individual localization clusters were rotated in the xy plane about their xyz centroids using the determined phase angle, and then these clusters were aligned on the basis of their xyz centroids to yield averaged NPC scaffolds (for example, Fig. 1g,h and Extended Data Fig. 3e). All the fitting routines were performed using MATLAB scripts available on GitHub (https://github.com/npctat2021/MINFLUX_NPC_Tracking.git).

Measuring the z-scaling factor

The z-axis data in 3D MINFLUX imaging required a correction to account for spherical aberrations caused by the difference in refractive index of the sample (approximately 1.33) and that of the immersion medium (1.51) used with the objective. The z-scaling factor of 0.7 recommended by the manufacturer of the MINFLUX microscope was calculated on the basis of simulations54. This z-scaling factor has been applied previously to 3D MINFLUX data2,16,17 and has been directly measured as 0.69 (ref. 55). The z-scaling factor used here was estimated from independent measurements of NPC scaffold structures as determined by HMSiR astigmatism imaging (see the ‘3D astigmatism imaging’ section). The advantage of this approach is that both MINFLUX and astigmatism measurements were made under identical conditions (the same buffer and added reagents, cell type, nanobodies, HMSiR labelling conditions and range of z heights above the surface) and the astigmatism measurements were independently calibrated for each day’s experiments by imaging beads while z stepping a nanostage7. As the z spacing between the two rings of the NPCs at the bottom of cell nuclei can be assumed to be identical for both imaging strategies, the astigmatism ring spacing of 51.5 ± 1.1 nm was used to correct the raw MINFLUX data, where the ring spacing was determined as 76.8 ± 0.8 nm (see Supplementary Table 2 and Extended Data Fig. 4). The z-scaling factor was therefore calculated as 51.5 nm/76.8 nm = 0.67. This value was used for all MINFLUX z-axis scalings. A direct comparison of the MINFLUX and astigmatism NPC images and the corresponding data is shown in Extended Data Fig. 4, and a summary of the associated parameters is given in Supplementary Table 2.

Identifying Imp α trajectories from JF549 localizations

After collecting the NPC scaffold data, the scanning and localization protocol for JF549 was implemented and continued for approximately 15–20 min. For tracking Imp α–JF549, the five iteration MINFLUX sequence was designed to be as fast as possible with an octahedral scan pattern in the last iteration, which yielded an xyz localization within a single step (Supplementary Table 3). The fifth iteration was repeated if insufficient photons were collected (20 or 25 minimum; see Supplementary Table 3) or to yield the next localization within the trajectory until the particle was lost. Unlike for HMSiR localizations in which the CFR check during imaging was set to a low value to select for high-quality localizations at the time of acquisition, for tracking, the CFR ratio was set to a large cut-off (more than 2.0) to avoid rejecting tracks that were temporarily interrupted. Instead, the CFR was checked during data analysis of the localization data. All detected tracks within the acquisition volume (z = 0 ± 400 nm) were identified with Abberior Imspector 16.3.15620 and Paraview 5.8.1 software and exported to MATLAB format. Imp α–JF549 trajectories were converted into red channel (HMSiR) coordinates via the alignment procedure discussed earlier. The data were curated by eliminating those tracks that did not have any localizations within a 400-nm cube centred on an NPC. Each trajectory was then rotated by the same angle as the NPC that it was linked to. The alignment routine was performed using MATLAB scripts available on GitHub (https://github.com/npctat2021/MINFLUX_NPC_Tracking.git). For trajectories that entered an NPC scaffold (|z| ≤ 25 nm), the tracks were verified as authentic using the criteria summarized in Extended Data Fig. 6c–f. Although there was some background fluorescence and leakage from HMSiR fluorescence within the permeabilized cells, tracks that resulted from this background were effectively eliminated with a DCR filter (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d). On the basis of the earlier results56, we used a CFR of less than 0.8 (Extended Data Fig. 6e). The EFO was used to eliminate background signals, but it also indicated that approximately 10–15% of transport trajectories had two JF549 dyes on Imp α instead of one (Extended Data Fig. 6f). This was an expected consequence of the under-labelling strategy. The reference angle in Fig. 3h,l was the localization nearest the pore midplane (z = 0), except for three cases of poor localization precision.

3D astigmatism imaging

Microscope system

The 3D astigmatism microscope system was described earlier7 and was used here without modification except that a ×2 magnifying lens was removed57 and either a Prime 95B or Kinetix22 CMOS camera (both from Teledyne Photometrics) was used for imaging, which yielded square pixels of 120 nm and 138 nm at camera plane, respectively. A TIRF-lock system provided a z stability for the coverslip of less than 3 nm for the duration of the experiment. The astigmatism was set to 60-nm root mean square (rms) deviation using a deformable mirror to generate the z-dependent spot ellipticity needed for 3D information. Orange (mEosEM) and red (HMSiR) fluorescence emission were collected with a quad-bandpass filter set (ZT405/488/561/640/rpcv2-UF2, Chroma). Data collection on this Zeiss 200M microscope was acquired using Micro-Manager 2.0 (ref. 58). The Mirao 52-e deformable mirror system (Imagine Optic) used for wavefront correction and to create astigmatism utilized CasAO 1.0 and MiCAO 1.3. The Nano-LPS200 piezo nano-positioning stage controlling a TIRF-lock stabilization system (Mad City Labs) was controlled by LabVIEW 2015. Image J (Fiji 1.52P), Origin 8.5, Kaleidagraph 5.01 and Microsoft Excel 16.76 (23081101) were used for data analysis, data presentation and simulations.

Sample preparation

Freshly split U2OS NUP96–mEGFP cells were grown overnight at less than 60% confluence on #1.5 coverslips (24 × 60 mm; 16004-312, VWR), which were pretreated with 0.01% poly-l-lysine (P4832, Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature and air-dried overnight. The next day, flow chambers (approximately 10 µl) were constructed by inverting a small coverslip (10.5 × 35 mm; 72191-35, Electron Microscopy Sciences) with beads of high-vacuum grease parallel to its short edges over the cells59. Cells within the flow chambers were permeabilized by incubating with digitonin (40 µg ml−1) in import buffer for 3 min. Permeabilized cells were washed once with 10 µl IB–PVP. Then, 10 µl of 150 nM NbGFP–HMSiR in IB–PVP was flowed onto the permeabilized cells and incubated for 3 min. The cells were washed (2 × 10 µl IB–PVP) and then Imp β1–mEosEM (0.5 µM) or a mixture of Imp β1 (0.5 µM), Imp α (0.5 µM) and NLS–BFP–mEosEM (0.5 µM) was added. After 10 min, the permeabilized cells were washed twice (2 × 10 µl IB–PVP) to remove unbound proteins. For Extended Data Fig. 9j–l, cells with bound Imp β1–mEosEM were incubated with ‘Ran mix’ (2 × 10 µl; 1.5 µM RanGDP, 1.5 µM NTF2, 1 mM GTP, 1 µM RanBP1 and 1 µM RanGAP in IB–PVP) for 10 min, and then washed (2 × 10 µl IB–PVP). For Extended Data Fig. 9n–p, cells with bound Imp NLS–BFP–mEosEM (cargo complexes) were incubated with ‘transport mix–high-α’ (2 × 10 µl; 1.5 µM RanGDP, 1.5 µM NTF2, 1.0 µM RanGAP, 1.0 µM RanBP1, 1 mM GTP, 0.5 µM Imp β1, 0.5 µM Imp α, 0.5 µM NLS–2×BFP and 2 µM GST–CAS in IB–PVP) for 10 min, and then washed (2 × 10 µl IB–PVP). Note that ‘transport mix–high-α’ is the same composition of proteins used in the simultaneous import–export MINFLUX experiments (‘transport mix’), except with a higher concentration of Imp α (non-fluorescent).

3D localizations

HMSiR localizations were acquired first (excitation = 641 nm; 50 ms per frame, twenty 500-frame videos with a 5-s gap between videos), and then the photoactivatable mEosEM was imaged (excitation = 561 nm; 70 ms per frame, thirty 1,000-frame videos with a 5-s gap between videos) in the presence of constant UV illumination (activation laser, 408 nm). Data analysis to identify and align NPC scaffolds and to then align mEosEM localizations with these scaffolds was performed as described earlier7. With minimum photon counts of 3,000 and 1,000 for HMSiR and mEosEM, respectively, the average precisions were 4.2–5.4 nm and 6–8.3 in xy, and 8.7–9.9 nm and 14.6–15.2 nm in z, determined as previously described7,57. Note that the precisions varied slightly for the two cameras used57.

Channel alignment

The two channels were aligned by imaging five 0.1-µm TetraSpeck microspheres (T7279, Thermo Fisher Scientific) embedded in 2% agarose, as previously described7, with a precision of 1–2 nm (xy) and 3–7 nm (z).

Confocal imaging and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

Confocal imaging and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) measurements were performed with a Luminosa single-photon counting confocal microscope (Picoquant). For confocal imaging of NPCs in U2OS cells decorated with mEosEM fusion proteins, samples were prepared as for astigmatism imaging, except that the final wash step before adding NbGFP–HMSiR and the mEosEM protein was 3 × 10 µl IB–PVP. Imaging of mEosEM was performed using 478-nm excitation in continuous-wave mode. FCS experiments of purified proteins were performed in buffers as indicated in Extended Data Fig. 10 using the FCS measurement function of the Luminosa system software (Luminosa 1.0.0.4067).

Error estimation and dye movement analysis

Jump histograms

Jump probability histograms summarize the measured distances between two successive localizations, either for static particles (for example, on the NPC scaffold) or for moving particles (for example, cargo movement around and through the NPC). The following jump probability distributions (equations (1)–(4)) were summarized earlier7 and are provided here for completeness. These distributions assume anisotropic translational movement described by a diffusion coefficient, D. All distributions are normalized (that is, the sum of all probabilities = 1):

One dimension:

$$p(x\,;D,t)\rmdx=\frac2b\sqrt4\pi Dt\exp \left(-\fracx^24Dt\right)\rmdx$$

(1)

where t is the time between successive localizations, b is the bin size of the jump distances, and x is the measurement axis for the displacements. This is a Gaussian (normal) distribution, except that we have assumed that all the jump distances are positive for easier comparison with the 2D and 3D cases, which necessitates the factor of 2.

Two dimensions:

$$p(r\,;D,t)\rmdr=\fracbr2Dt\exp \left(-\fracr^24Dt\right)\rmdr$$

(2)

where r2 = x2 + y2.

Three dimensions:

$$p(R\,;D,t)\rmdR=\fracbR^2\sqrt4\pi (Dt)^\frac32\exp \left(-\fracR^24Dt\right)\rmdR$$

(3)

where R2 = x2 + y2 + z2. If there are distinct molecular populations with different diffusion coefficients, a weighted sum can be generated. For example, for two species in 3D:

$$p(R\,;D_1,D_2,A,t)\rmdR=[Ap(R\,;D_1,t)+(1-A)p(R\,;D_2,t)]\rmdR$$

or,

$$p(R\,;D_1,D_2,A,t)\rmdR=\fracbR^2\sqrt4\pi \left[\fracA(D_1t)^\frac32\exp \left(-\fracR4D_1t\right)+\frac1-A(D_2t)^\frac32\exp \left(-\fracR4D_2t\right)\right]\rmdR$$

(4)

where A is a weighting factor for the two distributions. In this case, there are three fitting parameters, D1, D2 and A for a fixed time step t.

Time-independent histograms

The jump probability histograms described by equations (1)–(4) are valid for equal time steps (t = constant). For larger t, the distributions become broader, a consequence of larger average jump distances. MINFLUX localizations are typically rejected unless a minimum number of photons are collected; this is typically rectified by repeating the localization process until the minimum photon limit is met, leading to unequal timesteps (see Extended Data Fig. 1). To correct for unequal timesteps, the probability distributions for isotropic diffusion can be converted to time-independent expressions with a change of variables. For completeness, this is demonstrated here for all three cases, although only the approach of the 3D case was used to analyse data (for example, Fig. 3p and Extended Data Fig. 5).

One dimensions:

Assume, \(u=\fracx^2t\)

Then: \(\rmdu=\frac2xt\rmdx\) and \(\sqrtu=\fracx\sqrtt\)

From equation (1),

$$\beginarraylp(x\,;D,t)\rmdx\,=\,\frac2b\sqrt4\pi Dt\exp \left(-\fracx^24Dt\right)\rmdx=\,\frac2b\sqrt4\pi Dt\fract2x\exp \left(-\fracx^24Dt\right)\frac2xt\rmdx\\ \,\,\,\,=\,\fracb\sqrt4\pi D\frac\sqrttx\exp \left(-\fracx^24Dt\right)\frac2xt\rmdx\endarray$$

or,

$$p(u\,;D)\rmdu=\fracb\sqrt4\pi Du\exp \left(-\fracu4D\right)\rmdu$$

(5)

Two dimensions:

Assume, \(u=\fracr^2t\)

Then: \(\rmdu=\frac2rt\rmdr\)

From equation (2),

$$p(r\,;D,t)\rmdr=\fracbr2Dt\exp \left(-\fracr^24Dt\right)\rmdr=\,\fracb4D\exp \left(-\fracr^24Dt\right)\frac2rt\rmdr$$

or,

$$p(u\,;D)\rmdu=\fracb4D\exp \left(-\fracu4D\right)\rmdu$$

(6)

Three dimensions:

Assume, \(u=\fracR^2t\)

Then: \(\rmdu=\frac2Rt\rmdR\) and \(\sqrtu=\fracR\sqrtt\)

From equation (3),

$$p(R\,;D,t)\rmdR=\fracbR^2\sqrt4\pi (Dt)^\frac32\exp \left(-\fracR^24Dt\right)\rmdR=\fracb2\sqrt4\pi (D)^\frac32\left(\fracR\sqrtt\right)\exp \left(-\fracR^24Dt\right)\frac2Rt\rmdR$$

or,

$$p(u\,;D)\rmdu=\fracb\sqrtu4\sqrt\pi (D)^\frac32\exp \left(-\fracu4D\right)\rmdu$$

(7)

If there are distinct molecular populations with different diffusion coefficients, a weighted sum can be generated. For two species in 3D:

$$p(u\,;D_1,D_2,A)\rmdu=[Ap(u\,;D_1)+(1-A)p(u\,;D_2)]\rmdu$$

or,

$$p(u\,;D_1,D_2,A)\rmdu=\,\fracb\sqrtu4\sqrt\pi \left[\fracA(D_1)^\frac32\exp \left(-\fracu4D_1\right)+\frac1-A(D_2)^\frac32\exp \left(-\fracu4D_2\right)\right]\rmdu$$

(8)

where A is a weighting factor for the two distributions. In this case, there are three fitting parameters, D1, D2, and A.

Simulations

Simulations were performed using the Jump Step Histogram Simulator60 to demonstrate the time independence of equation (7). Three-dimensional translational steps were randomly selected from a normal distribution centred around the starting position with a step variance (Var) of Var(R) = 6Dt [with Var(x) = 2Dxt, Var(y) = 2Dyt, and Var(z) = 2Dzt]. The simulations yielded diffusional trajectories unconstrained by boundary conditions (such as the NPC scaffold) with a defined number of localizations per trajectory. In the case of NbGFP–HMSiR localizations, diffusional trajectories correspond to sample drift. For the Imp α–JF549 localizations, the diffusional trajectories approximate the jump steps of the protein interacting with the NPC. The simulation program allows for the inclusion of both sample drift and particle movement simultaneously, modelled identically. When the jump (R) histograms shown in Extended Data Fig. 5a were replotted as R2/t histograms, the time dependence vanished (Extended Data Fig. 5b), as predicted by equation (7). The Jump Step Histogram Simulator program60 includes additional features to approximate potentially relevant motions of the dye. To approximate a ‘jiggle’, that is, dye movement around a central location, the position of the dye was selected from a normal distribution around a centroid with σ = jiggle. Jiggle was used to approximate the movement of the HMSiR dye around its attachment point to the NPC scaffold, that is, the linkage error, or the localized, constrained movement of Imp α–JF549 within the NPC permeability barrier network. Particle movement was modelled on the basis of its centroid. Hence, rotational error (similar to the linkage error) results from the distance between the dye on the surface of the protein and the particle centroid, for example, rotation of the import and export complexes within the NPC permeability barrier. This rotational error (sphere rotation) was modelled by randomly selecting a position on the surface of a sphere with a defined radius. Both jiggle and rotational error were assumed to equilibrate rapidly such that randomization occurred between timesteps, but nonetheless that distinct positions were populated during measurements.

The probability distributions in equations (1)–(8) do not account for the precision of the measurements. This precision was included in the simulation program (Jump Step Histogram Simulator60) by assuming a normally distributed measurement precision (σ) for all localizations. For MINFLUX, σz is typically less than σx ≈ σy (refs. 2,17), so these were independently adjustable in the simulations; nonetheless, on the basis of Fig. 1i, σx/σy = 0.93 and σx/σz = 1.55 were assumed for all simulations. The effects of localization precision on the jump and R2/t histograms are shown in Extended Data Fig. 5c,d. Of note, in the presence of localization precision, the R2/t histograms were no longer independent of t (Extended Data Fig. 5d). This finding led to a wider conclusion that illustrates an important feature of R2/t histograms, namely, that R2/t histograms have different sensitivities to parameters influencing jump step histograms. The magnitude of jump steps squared (R2) for sample drift or particle movements depends on t and, hence, dividing by t makes the values time independent (Extended Data Fig. 4b). However, localization precision, jiggle (linkage error) and rotational error do not depend on time (as modelled here): they yield similar effects on the measurements of R irrespective of the length of the time step. Consequently, they yield effects on R2/t histograms that, as a group, are distinct from the effects of D. This dichotomy is dramatically illustrated in Fig. 3o,p. Although jump histograms could be fit with multiple combinations of parameters, R2/t histograms were substantially more difficult to fit. Consequently, reproducing both histograms with the same parameters significantly increased confidence in the goodness of fit. Critically, the time steps and precision must be accounted for when using simulations to approximate the experimental data.

Simulations that include localization precision, diffusional drift and variable time steps were used to approximate the data in Fig. 1j. As the MINFLUX measurements yielded variable timesteps, the simulations included timesteps distributed according to the observed experimental frequencies (Extended Data Fig. 1). As these data in Fig. 1j reflect the distances between successive localizations of HMSiR fluorophores affixed to or tethered to static objects (NPCs), inclusion of a non-zero diffusion coefficient to improve the fit was not expected but turned out to be the most straightforward way to fit the data. We expect that this ‘diffusional drift’ is not sample drift that would generate large displacements over the total imaging time, as this would make the assembly of the NPC scaffold from the data impossible. Rather, the diffusional drift is confined and models the movement of the dye centroid on the NPC scaffold, for example, to favourable positions enabled by linkage error, or conformational shifts or jiggles of the NPC scaffold. This diffusional drift was instrumental to reproduce the experimental centroid deviations from simulated data (Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 5i).

The data in Fig. 3o,p were fit using simulations that included localization precision, a diffusion coefficient and variable time steps. The localization precisions were independently adjustable for the three distinct molecular species, to account for the fact that the precision of static and moving particles are expected to be different. The effect of localization precision is clearly identified in an R2/t histogram (Extended Data Fig. 5d), and this was the primary initial clue that suggested to us that the precision estimates obtained from centroid deviations were too high. The Imp α–JF549 tracking data revealed that R and t were largely independent (Extended Data Fig. 5l), indicating that the jump histogram (Fig. 3o) largely reflected localization error rather than diffusive motion. This interpretation was borne out by the more complex model used to fit the data and reproduce the R2/t histogram (Fig. 3p).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.