Materials

SiO2 colloidal particles with various sizes (140 nm to 5 μm, 5 wt%), green-fluorescent SiO2 (1 μm, excitation/emission: 497/530 nm, 2.5 wt%) and red-fluorescent polystyrene nanospheres (500 nm and 2.5 μm, excitation/emission: 530/607 nm, 2.5 wt%) were purchased from microParticles GmbH. Mineral Oil Rotational Viscosity Standard (494.0 mPa s), oleic acid (technical grade, 90%), silicone oil AR20 (viscosity: approximately 20 mPa s), CTAB (98%), SDS (98.5%), PEG (Mn: 400), PF108 (Mn: 14,600), TiO2 NWs (powder, 100 nm × 10 μm), WO3 NWs (powder, 50 nm × 10 μm), Al2O3 NWs (powder, 2–6 nm × 200–400 nm), CdTe quantum dots (powder, COOH functionalized, fluorescent emission: 710 nm), iron oxide (Fe3O4) powder (50–100 nm, 97%), Fe3O4 (20 nm, 5 mg ml−1, dispersed in H2O), TiO2 nanoparticles (150 nm, 900 nm, 5 wt%, dispersed in H2O), Au urchin nanoparticles (50 nm, in 0.1 mM PBS), Pt nanoparticles (powder, 50 nm, 99.9%), silver (Ag) powder (<100 nm, PVP as dispersant, 99.5%), orange fluorescent PLGA nanospheres (excitation/emission: 530/582 nm, 100 nm), diamond nanopowder (<10 nm, 97%), trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl) silane (97%), sodium chloride (NaCl, 99%), H2O2 (30% w/w in H2O) and propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate (PGMEA, 99.5%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Isopropyl alcohol (IPA, 99.9%) was purchased from Carl Roth GmbH. IPS photoresist was purchased from Nanoscribe GmbH. Immersion oil 518 F (viscosity of about 500 mPa s) was purchased from Fisher Scientific.

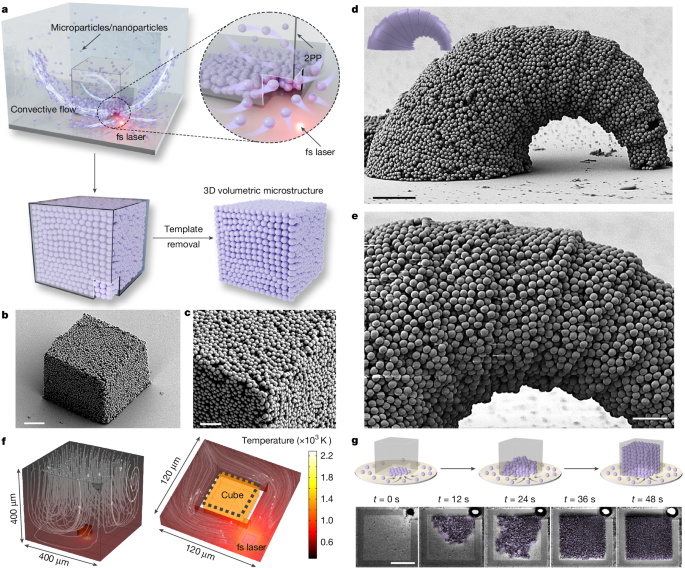

Fabrication of 3D hollow microtemplates

The 3D hollow polymeric templates were designed using SOLIDWORKS 2021 and fabricated by direct laser writing using a commercial Photonic Professional GT system (Nanoscribe GmbH). The templates were printed with commercial IPS photoresist in oil-immersion mode with a 63× objective and printed on a fused glass substrate that had been treated overnight with trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl) silane vapour. The laser power and printing speed were 50 mW and 50,000 μm s−1, respectively. After printing, the structures were developed in IPA solution for 5 min to remove non-polymerized photoresist. The templates were then directly used for the particle assembly in particle-laden dispersions. For aqueous dispersion, the high thermal conductivity of water can limit photothermal efficiency. To enhance this, a 5-nm Cr layer followed by a 5-nm Au layer was sputtered onto the substrate, improving photothermal performance.

Process of the optofluidic 3D microfabrication/nanofabrication

SiO2 particles of different diameters (150 nm and 1 μm) were used in the assembly experiments. To redisperse SiO2 particles into various solvent systems, 100 μl of as-received aqueous SiO2 solution was first centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 3 min. The supernatant was discarded and the collected SiO2 precipitate was dried by heating at 60 °C for 2 h. The dried SiO2 powder was then redispersed in 1 ml of various solvents (for example, immersion oil, oleic acid) and sonicated for 1 h to ensure thorough dispersion. These hydrophilic SiO2 particles can remain dispersed in various oils in the experimental timescale owing to the high viscosity of the medium, which helps prevent clogging the template openings by large agglomerations during assembly (Supplementary Fig. 15). The resulting SiO2 suspension was used for the assembly experiments. It should be noted that other colloidal materials were also redispersed in appropriate solvents using a similar procedure to perform the assembly experiments. Furthermore, co-assembly of different materials can be obtained by preparing a mixed suspension through physical blending of various particles, as demonstrated in Fig. 4i, in which SiO2 microspheres with 600 nm and 1 μm diameter were co-assembled into a single structure. The detailed parameters of colloidal materials used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

For experiments conducted in aqueous solutions with varying NaCl concentrations, 150-nm SiO2 particles were selected because of their reduced gravitational settling, ensuring system stability before laser-induced assembly. SiO2 dispersions were prepared with different NaCl concentrations at a particle concentration of 1 wt%. To study assembly dynamics and ensure clear observation, large SiO2 particles (1 μm) were used in various solvent systems, including aqueous solutions containing surfactants and oil-based solvents. A 100-μl aliquot of each prepared solution was placed inside a square PDMS spacer (1 cm side length, about 200 μm height). The spacer was sealed with a cover glass to prevent evaporation. A fs laser beam (780 nm, 80 MHz) with a scanning area of 2 × 2 µm2 was continuously applied at the corner of the printed hollow template to guide particle assembly. After the assembly process, the substrate was sequentially washed with IPA and deionized water, followed by mild sonication to remove any residual colloidal particles surrounding the microstructure.

To create 3D structures or devices made from different particles, we used a sequential, multistep assembly procedure. Suspensions of different particles were introduced successively, with a washing step between each stage to remove excess particles and prevent cross-interference. For instance, when creating alphabet letters ‘P’ and ‘I’, a suspension of 600-nm SiO2 was first used to assemble ‘I’. The excess suspension was then rinsed away with IPA and water to ensure clean conditions for the next step, after which a suspension of 1-µm SiO2 particles was introduced to assemble ‘P’. By repeating these processes, several particle systems can be used to construct distinct structures at predefined locations on a single substrate or to achieve seamless integration within a single microstructure, thereby enabling the creation of multifunctional microdevices.

Finally, it should be noted that excessively strong inter-particle attraction can lead to the formation of large clusters that clog the openings, preventing complete filling of the 3D structures (Supplementary Video 15). This issue can be mitigated by optimizing the size and distribution of template openings, as shown in Supplementary Discussion 1 and Supplementary Figs. 16–18.

Template removal

To completely remove the outer-layer polymer template and maintain the structural integrity, the colloidal-assembled microstructures were subjected to mild O2 plasma treatment for 6 h with a plasma cleaner machine (Tergeo-EM, PIE Scientific) at 75 W power and an O2 flow rate of 20 sccm. To further enhance interfacial bonding, the microstructures were annealed in air at 600 °C for 2 h with a heating rate of 2 °C min−1. For faster template removal, a high-power Plasma Asher (MPR-6) can also be used.

Fabrication of microfluidic chips for particle separation

The microfluidic channel was fabricated using the Nanoscribe system with IPG-780 photoresist. To enhance fabrication efficiency, template models with an asymmetric hole configuration were designed, similar to the one shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. This design enabled direct printing of the microchannel without requiring polymer template removal after particle assembly. Specifically, 100 μl of IPG-780 was dispensed onto the substrate and pre-baked at 100 °C for 1 h. A microchannel (2 mm length, 40 μm width, 15 μm height) was then printed using the Nanoscribe system with a 63× objective. The laser power and printing speed were set to 30 mW and 80,000 μm s−1, respectively. After printing, the substrate was developed in PGMEA for 20 min, followed by IPA for 1 min to remove unpolymerized photoresist. For the microfluidic separation experiments, colloidal particle solutions containing 30 v/v% IPA were prepared to improve wettability within the microchannel.

Microrobot motion experiments

The fabricated microrobots were first treated with O2 plasma for 5 min to change their wettability before use. Afterwards, these microrobots were scratched off the glass and dispersed in deionized water. The microrobot suspension was then added to a piece of glass slide and observed under an optical microscope (ZEISS Axio Imager 2). The magnetically actuated tumbling was conducted under a uniform rotating field with an amplitude of 10 mT and frequency of 1–120 Hz. The light-driven motion is powered by a UV light-emitting diode with a wavelength of 365 nm (Thorlabs).

Microscopy characterization

The real-time particle assembly process was recorded using a built-in AxioVision Live-View camera in the Nanoscribe system. The recorded videos were analysed using the Manual Tracking plugin in Fiji software to determine the flow speed. The microfluidic separation experiments were recorded using an optical microscope (ZEISS Axio Imager 2). The SEM and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) images were obtained using a Gemini field-emission SEM 500 at an acceleration voltage of 5 or 20 kV. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were acquired using a Philips CM200 TEM with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The fluorescent images were captured by a SP8 Leica confocal microscope and the raw data were processed and colourized using the built-in software LAX. The excitation wavelength was set to 552 nm with 10% intensity and the emission wavelength was collected at 630–700 nm.

Zeta potential measurement

The zeta potential of SiO2 (140 nm and 1 μm) colloidal particles dispersed in various solvents was measured in a Zetasizer Ultra system (Malvern). The viscosity and relative permittivity of solutions were set at 8.9 × 10−4 Pa s and 78.5, respectively. The final zeta potential of SiO2 particles was obtained by averaging the results of five independent measurements.

Finite-element simulations

A 3D model was built with the COMSOL Multiphysics package (version 6.0) to simulate the fluid flow around a 2PP-printed hollow microcube. The size of the hollow cube was 40 × 40 × 40 µm3 with a hole of 10 × 10 × 10 µm3 at one of its corners (Supplementary Fig. 19). The computational domain was a cubic box of 400 × 400 × 400 µm3, with the upper surface set as a free boundary at a temperature of T0 = 293.5 K. The four side boundaries were modelled with symmetric boundary conditions, whereas the remaining boundaries were set as no-slip conditions. A laser with a scanning area of 2 × 2 µm2 was applied to reach T1 = 2,293 K. The box was filled with water and the density variation induced by heat transfer drove the flow through buoyancy. The temperature distribution and fluid flow field surrounding the cube were computed using the laminar flow and conjugate heat transfer modules within the box.

Theoretical analysis

To explain the competition between inter-particle interactions and particle–fluid interactions during the assembly process, a model system in which SiO2 particles assemble in aqueous solutions with various NaCl concentrations was used. On the basis of our experimental observations (Fig. 2b), the particle suspension initially resided in a metastable dispersion state, in which the attractive van der Waals interaction outweighed the electrostatic repulsion. In this system, the work done by the particle–fluid interaction during an infinitesimal displacement ds is represented by

$$\Delta {W}_{{\rm{f}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{u}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{d}}}=6{\rm{\pi }}\mu Rv\times ds$$

(1)

in which μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, R is the particle radius and v is the flow velocity.

The difference in interaction potential between particles is represented by

$$\Delta {U}_{{\rm{DLVO}}}={F}_{{\rm{DLVO}}}\times {ds}.$$

(2)

DLVO force (FDLVO) consists of two parts: van der Waals force (attractive force for the formation of colloidal clusters) and EDL repulsion force among particles.

The van der Waals force between particle and particle (FvdW–pp) can be described by

$${F}_{{\rm{vdW}}-{\rm{pp}}}(h)=\frac{A}{6}\left(-\frac{4{R}^{2}(2R+h)}{{[(4R+h)h]}^{2}}-\frac{4{R}^{2}}{{(h+2R)}^{2}}+\frac{8{R}^{2}}{h(4R+h)(h+2R)}\right)$$

(3)

in which A is the Hamaker constant and h is the closest distance to the two-particle surface.

The EDL energy50 between particle and particle can be described by

$${W}_{{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{L}}-{\rm{p}}{\rm{p}}}(h)={\rm{\pi }}{\varepsilon }_{0}{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{l}}}R{\zeta }^{2}\left[{\rm{l}}{\rm{n}}(1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-2\kappa h})+{\rm{l}}{\rm{n}}\left(\frac{1+{{\rm{e}}}^{-\kappa h}}{1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-\kappa h}}\right)\right]$$

(4)

in which ζ is the zeta potential on the solid–fluid interface, ε0 and εl are the dielectric permittivities of vacuum and water, respectively, \({\kappa }^{-1}=\sqrt{\frac{{\varepsilon }_{0}{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{l}}}{K}_{{\rm{B}}}T}{2{N}_{{\rm{A}}}{{\rm{e}}}^{2}I}}\) is the Debye length, \(I=0.5\sum {z}_{{\rm{i}}}^{2}{\rho }_{{\rm{i}}}\), ρi is the ion concentration and zi is the number of charges carried by the ion.

The EDL repulsion force (FEDL–pp) is then described by

$${F}_{{\rm{EDL}}-{\rm{pp}}}(h)=-\frac{{\rm{\partial }}{W}_{{\rm{EDL}}-{\rm{pp}}}(h)}{{\rm{\partial }}h}$$

(5)

$${F}_{{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{L}}-{\rm{p}}{\rm{p}}}(h)=-2{\rm{\pi }}{\varepsilon }_{0}{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{l}}}R\kappa {\zeta }^{2}\left[\frac{{{\rm{e}}}^{-2\kappa h}}{1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-2\kappa h}}-\frac{{{\rm{e}}}^{-\kappa h}}{1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-2\kappa h}}\right]$$

(6)

in which h → 0

$$\mathop{{\rm{l}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{m}}}\limits_{h\to 0}\,{F}_{{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{L}}-{\rm{p}}{\rm{p}}}(h)={\rm{\pi }}{\varepsilon }_{0}{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{l}}}R\kappa 2{\zeta }^{2}\frac{3\kappa h}{2\kappa h}=3{\rm{\pi }}{\varepsilon }_{0}{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{l}}}R\kappa {\zeta }^{2}$$

(7)

Then the ΔUtotal can be described by

$$\Delta {U}_{{\rm{t}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}}=({F}_{{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{L}}-{\rm{p}}{\rm{p}}}+{F}_{{\rm{v}}{\rm{d}}{\rm{W}}-{\rm{p}}{\rm{p}}}+6{\rm{\pi }}\mu Rv)\times ds$$

(8)

When increasing the ionic strength of the system, the FEDL–pp is gradually screened. Therefore, colloidal particle clustering becomes more favourable.

The tendency of the system to form clusters can then be evaluated by examining changes in Utotal. When ΔUtotal < 0, the attractive interaction dominates in the fluid flow, leading to the cluster formation of colloidal particles; otherwise, the repulsive interaction dominates and particles would remain dispersed. The detailed information of all physical parameters used in this study, including their corresponding symbols and values, are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. The phase diagram in Fig. 2e showing the dispersing and clustering domains of colloidal particles can be obtained with equation (8) through MATLAB.