You have full access to this article via your institution.

People wade through Mumbai’s flooded streets during monsoon rains in August.Credit: Indranil Aditya/NurPhoto/Getty

The monsoon season lasts from June to September in southern Asia. During this period, nearly 60% of Bangladesh’s population is at risk from floods. Last year, some five million people were affected by flash floods caused by heavy rains. Increasingly heavy rains are submerging parts of India and Pakistan, too. This year alone, 45% of India has experienced extreme rainfall, leading to some 1,500 deaths. And, in Pakistan, two million people have had to evacuate their homes and more than 800 have died.

Read the paper: Mortality impacts of rainfall and sea-level rise in a developing megacity

More extreme weather events are among the expected impacts of climate change, but a study in Nature now shows that the reported number of excess deaths — how many more deaths occurred than would otherwise be expected — because of rainfall and flooding is probably a considerable undercount1. This work is part of an expanding body of knowledge suggesting that many more people are vulnerable to extreme weather events than are being recorded in official data.

Such studies need to re-energize discussions taking place this week at the COP30 climate conference in Belém, Brazil — including those about the size and make-up of a fund being set up to compensate people for the losses and damages caused by climate change. Some initial reports from Brazil suggest that expectations for COP30 are low even by the standards of COP meetings. And that isn’t good news for anyone.

In many countries, calculations of deaths from heavy rains are based on whether relevant words such as flooding or drowning are mentioned on a death certificate. However, fatalities caused indirectly by rainfall or flooding — as when someone loses their life because of electrocution, a waterborne infectious disease or falling debris — will not mention water as the cause of death. Researchers say that this is a key reason why the actual numbers are likely to be higher than those recorded officially.

Extreme rainfall poses the biggest risk to Mumbai’s most vulnerable people

In their study, economists Tom Bearpark at Princeton University in New Jersey, Ashwin Rode at the University of Chicago in Illinois and Archana Patankar at Green Globe Consulting in Mumbai, India, aimed to improve the accuracy of rainfall-related mortality assessments. Their modelling study focuses on Mumbai. As well as being India’s financial hub, the city also houses at least one million people who live in informal settlements. These consist of unsafe, often overcrowded, homes that lack basic necessities such as running water, access to a toilet and electricity.

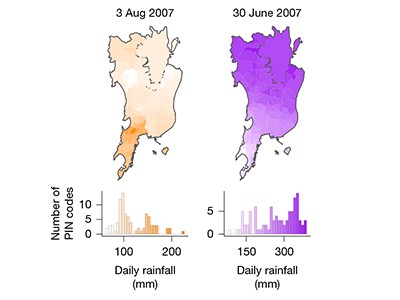

The researchers found that, between 2006 and 2015, some 2,500 lives were lost yearly during the monsoon. They also show that many who died from rainfall-related causes were young children and women, and most lived in informal settlements. Their figure for mortality from rainfall in Mumbai is an order of magnitude greater than that recorded officially for the state of Maharashtra, which includes Mumbai, for 2006–14.

Bearpark, Rode and Patankar are not alone in their conclusion that deaths caused by extreme weather events are being undercounted in official statistics. In 2024, scientists Rachel Young and Solomon Hsiang at the University of California, Berkeley, estimated2 that, between 1930 and 2015, 7,000–11,000 excess deaths annually in the United States were caused by 501 tropical cyclones (or hurricanes). This contrasts with an average of 24 deaths reported in government statistics as directly attributable to such events. Unrecorded causes included limited or no access to health care, and conditions such as sudden infant death syndrome and cardiovascular diseases. Very young children (under one year old), individuals aged 65 years or older and Black people were the most vulnerable. Other studies using similar approaches have found that deaths from extreme heat are also being undercounted.

The ‘implementation COP’: why the Belém summit must ratchet up climate action

Recording the number and causes of deaths accurately matters. It matters to families so they know why loved ones have died. Knowing that many more people are at risk of death from extreme weather events also matters to all those in positions of responsibility in their countries, because it means that they can do something about the underlying issues before it is too late.

We know, for example, that around 25% of the world’s urban population lives in informal settlements, a number that has been increasing since 2020. Efforts must be redoubled to improve conditions given that people living in such housing are the most vulnerable to extreme weather.

At the same time, a fund for compensating poorer countries for the climate impacts caused mainly by the emissions of richer ones will need to be resourced sufficiently. The new loss-and-damage fund will issue its first call for proposals at COP30. Last year, an independent expert group on climate finance estimated that poorer countries would need at least US$250 billion a year by 2030 to pay for losses and damages from extreme-weather effects3. Taking excess mortality as a proxy, those costs are probably an underestimate, too. These are all reasons for COP delegates to bite the bullet and agree to a credible, accelerated plan to reduce the root cause of extreme weather: planet-warming emissions.