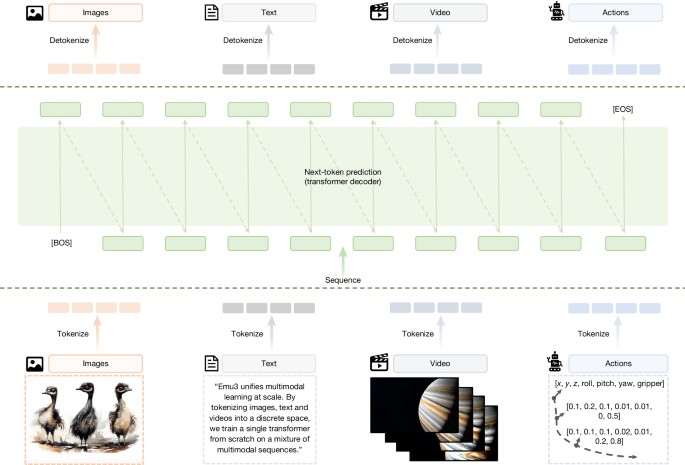

Tokenizer design

A unified tokenizer discretizes texts, images and videos into compact token sequences using shared codebooks. This enables text and vision information to reside in a common discrete space, facilitating autoregressive modelling. For text tokens and control tokens, we leveraged a byte pair encoding (BPE)-based text tokenizer for tokenization, whereas a vector quantization (VQ)-based visual tokenizer was used to discretize images and videos into compact token sequences.

Text tokenizer

For text tokenization, we adopted Qwen’s tokenizer49, which uses byte-level byte-pair encoding with a vocabulary encompassing 151,643 regular text tokens. To reserve sufficient capacity for template control, we also incorporated 211 special tokens into the tokenizer’s vocabulary.

Vision tokenizer

We trained the vision tokenizer using SBER-MoVQGAN14, which can encode a 4 × 512 × 512 video clip or a 512 × 512 image into 4,096 discrete tokens from a codebook of size 32,768. Our tokenizer achieved 4× compression in the temporal dimension and 8 × 8 compression in the spatial dimension and is applicable to any temporal and spatial resolution. Building on the MoVQGAN architecture50, we incorporated two temporal residual layers with three-dimensional convolution kernels into both the encoder and decoder modules to perform temporal downsampling and enhance video tokenization capabilities. The tokenizer was trained end-to-end on the LAION high-resolution image dataset and the InternVid51 video dataset using combined objective functions of Euclidean norm (L2) loss, learned perceptual image patch similarity (LPIPS) perceptual loss52, generative adversarial network (GAN) loss and commitment loss. Further details on video compression metrics, the impact of codebook size, and comparisons between the unified and standalone image tokenizers are provided in section 1 of the Supplementary Information.

Architecture design

Emu3 uses a decoder-only Transformer with modality-shared embeddings. We used RMSNorm53 for normalization and GQA54 for attention mechanisms, as well as the SwiGLU55 activation function and rotary positional embeddings56. Biases in the qkv and linear projection layers were removed. In addition, a dropout rate of 0.1 was implemented to improve training stability. Overall, the model contains 8.49 billion parameters, including 32 layers with a hidden size of 4,096, intermediate size of 14,336 and 32 attention heads (8 key-value heads). The shared multimodal vocabulary comprises 184,622 tokens, enabling consistent representation across language and vision domains.

Architectural comparisons with diffusion models

To fairly compare the next-token prediction paradigm with diffusion models for visual generation tasks, we used Flan-T5-XL57 as the text encoder and trained both a 1.5B diffusion transformer58,59 and a 1.5B decoder-only transformer60 on the OpenImages61 dataset. The diffusion model leverages the variational autoencoder from SDXL20, whereas the decoder-only transformer uses the video tokenizer in Emu3 to encode images into latent tokens. Both models were trained with identical configurations, including a linear warm-up of 2,235 steps, a constant learning rate of 1 × 10−4 and a global batch size of 1,024. As shown in Fig. 3c, the next-token prediction model consistently converged faster than its diffusion counterpart for equal training samples, challenging the prevailing belief that diffusion architectures are inherently superior for visual generation.

Architectural comparisons with encoder + LLM compositional paradigm

To fairly evaluate different vision–language architectures, we compared three model variants (trained without any pretrained LLM initialization) on the I2T validation set (an image-understanding task), as shown in Fig. 3b. All models were trained on the EVE-33M multimodal corpus35, using a global batch size of 1,024, a base learning rate of 1 × 10−4 with cosine decay scheduling and 12,000 training steps, and evaluated on a held-out validation set of 1,024 samples with comparable parameters. The models compared were: (1) a decoder-only model that consumes discrete image tokens as input (Emu3 variant, 1.22B parameters); (2) a late-fusion architecture comprising a vision encoder and decoder (LLaVA-style variant, 1.22B = 1.05B decoder + 0.17B vision encoder); and (3) a late-fusion architecture initialized with a CLIP-based vision encoder (LLaVA-style variant, 1.35B = 1.05B + 0.30B). The late-fusion LLaVA-style model initialized with a pretrained CLIP vision encoder showed substantially lower validation loss. Notably, when that pretraining advantage was removed, the apparent superiority of the encoder-based compositional architecture was largely diminished. The decoder-only next-token prediction model showed comparable performance, challenging the prevailing belief that encoder + LLM architectures are inherently superior for multimodal understanding. When evaluated under equal scratch training conditions, without prior initialization from LLMs and CLIP, it matched compositional encoder + LLM paradigms in terms of learning efficiency. Further architectural analyses are provided in section 2.1 of the Supplementary Information.

Data collection

Emu3 was pretrained from scratch on a mix of language, image and video data. Details of data construction, including sources, filtering and preprocessing, are provided in Extended Data Table 7. Further information on dataset composition, collection pipelines and filtering details is provided in section 3.1 of the Supplementary Information.

Pretraining details

Data format

Images and videos were resized to areas near 512 × 512 while preserving the aspect ratio during pretraining. We inserted special tokens [SOV], [SOT] and [EOV] to delimit multimodal segments:

$$[\text{BOS}]\{\text{caption text}\}[\text{SOV}]\{\text{meta text}\}[\text{SOT}]\{\text{vision tokens}\}[\text{EOV}][\text{EOS}],$$

where [BOS] and [EOS] mark the start and end of the whole sample, [SOV] marks the start of the vision input, [SOT] marks the start of vision tokens, and [EOV] indicates the end of the vision input. In addition, [EOL] and [EOF] were inserted into the vision tokens to denote line breaks and frame breaks, respectively. The ‘meta text’ contains information about the resolution for images; for videos, it includes resolution, frame rate and duration, all presented in plain text format. We also moved the ‘caption text’ field in a portion of the dataset to follow the [EOV] token, thereby constructing data aimed at vision understanding tasks.

Training recipe

Pretraining followed a three-stage curriculum designed to balance training efficiency and optimization stability. Stage 1 used a learning rate of 1 × 10−4 with cosine decay, no dropout and a sequence length of 5,120. This configuration enabled rapid early convergence; however, the absence of dropout eventually led to optimization instability and model collapse in late training. Stage 2 therefore introduced a dropout rate of 0.1, which stabilized optimization while retaining the warm-start benefits established in stage 1. Stage 3 extended the context length to 65,536 tokens to accommodate video–text data. The sampling ratio gradually shifted from image–text pairs towards video–text pairs. This curriculum substantially improved overall efficiency: the first two stages focused on image data for stable and cost-effective initialization, whereas the third stage expanded the context window and incorporated video data for full multimodal training. Tensor and pipeline parallelism remained constant across stages, with context parallelism scaling from 1 to 4 only in stage 3 to support the extended sequence length. Further implementation details including multimodal dropout for stability, token-level loss weighting, LLM-based initialization and mixture-of-experts configuration are provided in section 3.2.3 of the Supplementary Information.

Post-training details

T2I generation

QFT. After pretraining, Emu3 underwent post-training to enhance visual generation quality. We applied QFT to high-quality image data while continuing next-token prediction with supervision restricted to vision tokens. Training data were filtered by the average of three preference scores: HPSv2.1 (ref. 62), MPS63 and the LAION-Aesthetics score64, and the image resolution was increased from 512 to 720 pixels. We set the batch size to 240 with a context length of 9,216, with the learning rate cosine decaying from 1 × 10−5 to 1 × 10−6 over 15,000 training steps. Subsequently, a linear annealing strategy was used to gradually decay the learning rate to zero over the final 5,000 steps of QFT training.

DPO. We further aligned generation quality with human preference using DPO13. For each prompt, the model generated 8–10 candidate images that were evaluated by three annotators on visual appeal and alignment. The highest and lowest scoring samples formed preference triplets \(({p}_{i},{x}_{i}^{{\rm{chosen}}},{x}_{i}^{{\rm{rejected}}})\) for optimization. Tokenized data from this process were reused directly during training to avoid retokenization inconsistencies. Emu3-DPO jointly minimizes the DPO loss and the next-token prediction loss, with a weighting factor of 0.2 applied to the supervised fine-tuning loss for stable optimization. During DPO training, we use a dataset of 5,120 prompts and train for one epoch with a global batch size of 128. The learning rate follows a cosine decay schedule with a brief 5-step warm-up and then decays to a constant value of 7 × 10−7. A KL penalty of 0.5 is applied to the reference policy to balance alignment strength and generation diversity.

We present the performance of Emu3 through automated metric evaluation on popular T2I benchmarks: MSCOCO-30K23, GenEval24, T2I-CompBench25, and DPG-Bench26. Evaluation details are provided in the Supplementary Information, section 4.1.2.

T2V generation

Emu3 was extended to T2V generation by applying QFT to high-quality video data (each sample was 5 s long, 24 fps), with strict resolution and motion filters to ensure visual fidelity. We set the batch size to 720 with a context length of 131,072, with the learning rate set to 5 × 10−5 over 5,000 training steps. We evaluated video generation using VBench27, which assesses 16 dimensions including temporal consistency, appearance quality, semantic fidelity and subject–background coherence. Evaluation details are provided in section 4.2.2 of the Supplementary Information.

Vision–language understanding

Emu3 was further adapted to vision–language understanding through a two-stage post-training procedure. In the first stage, the model was trained on 10 million image–text pairs using a batch size of 512, mixing image-understanding data with pure language data while masking losses on vision tokens for text-only prediction. All images were resized to approximately 512 × 512 while preserving the aspect ratio. In the second stage, we performed instruction tuning on 3.5 million question–answer pairs sampled from ref. 65, also using a batch size of 512; images with shorter or longer resolution were clipped to the 512–1,024 pixel range. For both stages, we used a cosine learning rate schedule with a peak learning rate of 1 × 10−5. Evaluation details are provided in section 4.3 of the Supplementary Information.

Interleaved image–text generation

We further extended Emu3 to interleaved image–text generation, in which structured textual steps are accompanied by corresponding illustrative images within a single output sequence. The model was fine-tuned end-to-end to autoregressively generate such multimodal sequences, leveraging the flexibility of the unified framework. Training was performed for 10,000 steps with a global batch size of 128 and a maximum sequence length of 33,792 tokens. Each sequence included up to 8 images, each resized to a maximum area of 5122 pixels while preserving the aspect ratio. We used the Adam optimizer with a cosine learning rate schedule and a base learning rate of 7 × 10−6 and applied a dropout rate of 0.1 with equal weighting between image and text losses. Further details on data formatting and visualization results are provided in section 4.4 of the Supplementary Information.

Vision–language–action models

We further extended Emu3 to vision–language–action tasks by fine-tuning it on the CALVIN66 benchmark, a simulated environment designed for long-horizon, language-conditioned robotic manipulation.

The model was initialized from Emu3 pretrained weights, whereas the action encoder used the FAST tokenizer31 with a 1,024-size vocabulary, replacing the last 1,024 token IDs of the language tokenizer. RGB observations from third-person (200 × 200) and wrist (80 × 80) views were discretized using the Emu3 vision tokenizer with a spatial compression factor of 8. Training used a time window of 20 and an action chunk size of 10, forming input sequences of two consecutive vision–action–vision–action frames. Loss weights were set to 0.5 for visual tokens and 1.0 for action tokens. The model was trained for 8,000 steps with a batch size of 192 and a cosine learning rate schedule starting at 8 × 10−5. During inference, it predicted actions online by means of a sliding two-frame window. Visualizations are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3. Although the CALVIN benchmark is simulation-based, Emu3’s vision–language–action formulation was designed with real-world deployment challenges in mind. The next-token prediction paradigm naturally conditions on arbitrary-length histories, allowing the model to integrate feedback over time and recover from partial or imperfect sensor inputs, thereby accommodating noisy sensors or delayed feedback. In practice, real-world robotic validation requires substantial data collection (for instance, time-consuming tele-operation or on-hardware rollouts) and system-level engineering efforts to ensure safety, latency guarantees and reliable actuation, which made large-scale evaluation on physical robots difficult within the scope of this work. Although large-scale physical-robot validation will be part of our future work, the simulation results show that Emu3 can model complex, interleaved perception–action sequences without task-specific components, indicating strong potential for transfer to real robotic systems.