Survey results suggest that peer reviewers are increasingly turning to AI.Credit: Panther Media Global/Alamy

More than 50% of researchers have used artificial intelligence while peer reviewing manuscripts, according to a survey of some 1,600 academics across 111 countries by the publishing company Frontiers.

Nearly one-quarter of respondents said that they had increased their use of AI for peer review over the past year. The findings, posted on 11 December by the publisher, which is based in Lausanne, Switzerland, confirm what many researchers have long suspected, given the ubiquity of tools powered by large-language models such as ChatGPT.

“It’s good to confront the reality that people are using AI in peer-review tasks,” says Elena Vicario, Frontiers’ director of research integrity. But the poll suggests that researchers are using AI in peer review “in contrast with a lot of external recommendations of not uploading manuscripts to third-party tools”, she adds.

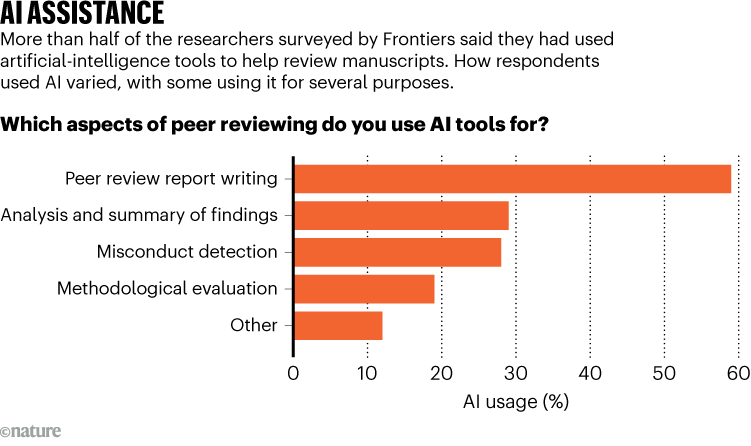

Source: Unlocking AI’s untapped potential, Frontiers

Some publishers, including Frontiers, allow limited use of AI in peer review, but require reviewers to disclose it. Like most other publishers, Frontiers also forbids reviewers from uploading unpublished manuscripts to chatbot websites because of concerns about confidentiality and compromising authors’ intellectual property.

The survey report calls on publishers to respond to the growing use of AI across scientific publishing and implement policies that are better suited to the ‘new reality’. Frontiers itself has launched an in-house AI platform for peer reviewers across all of its journals. “AI should be used in peer review responsibly, with very clear guides, with human accountability and with the right training,” says Vicario.

“We agree that publishers can and should proactively and robustly communicate best practices, particularly disclosure requirements that reinforce transparency to support responsible AI use,” says a spokesperson for the publisher Wiley, which is based in Hoboken, New Jersey. In a similar survey published earlier this year, Wiley found that “researchers have relatively low interest and confidence in AI use cases for peer review,” they add. “We are not seeing anything in our portfolio that contradicts this.”

Checking, searching and summarizing

Frontiers’ survey found that, among the respondents who use AI in peer review, 59% use it to help write their peer-review reports. Twenty-nine per cent said they use it to summarize the manuscript, identify gaps or check references. And 28% use AI to flag potential signs of misconduct, such as plagiarism and image duplication (see ‘AI assistance’).

Mohammad Hosseini, who studies research ethics and integrity at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois, says the survey is “a good attempt to gauge the acceptability of the use of AI in peer review and the prevalence of its use in different contexts”.

AI is transforming peer review — and many scientists are worried

Some researchers are running their own tests to determine how well AI models support peer review. Last month, engineering scientist Mim Rahimi at the University of Houston in Texas designed an experiment to test whether the large language model (LLM) GPT-5 could review a Nature Communications paper1 he co-authored.

He used four different set-ups, from entering basic prompts asking the LLM to review the paper without additional context to providing it with research articles from the literature to help it to evaluate his paper’s novelty and rigour. Rahimi then compared the AI-generated output with the actual peer-review reports that he had received from the journal, and discussed his findings in a YouTube video.

His experiment showed that GPT-5 could mimic the structure of a peer-review report and use polished language, but that it failed to produce constructive feedback and made factual errors. Even advanced prompts did not improve the AI’s performance — in fact, the most complex set-up generated the weakest peer review. Another study found that AI-generated reviews of 20 manuscripts tended to match human ones but fell short on providing detailed critique.

Rahimi says the exercise taught him that AI tools “could provide some information, but if somebody was just relying on that information, it would be very harmful”.