Omar Yaghi, who was awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry on Wednesday, emigrated from Jordan to the United States as a teenager.Credit: Brittany Hosea-Small/UC Berkeley

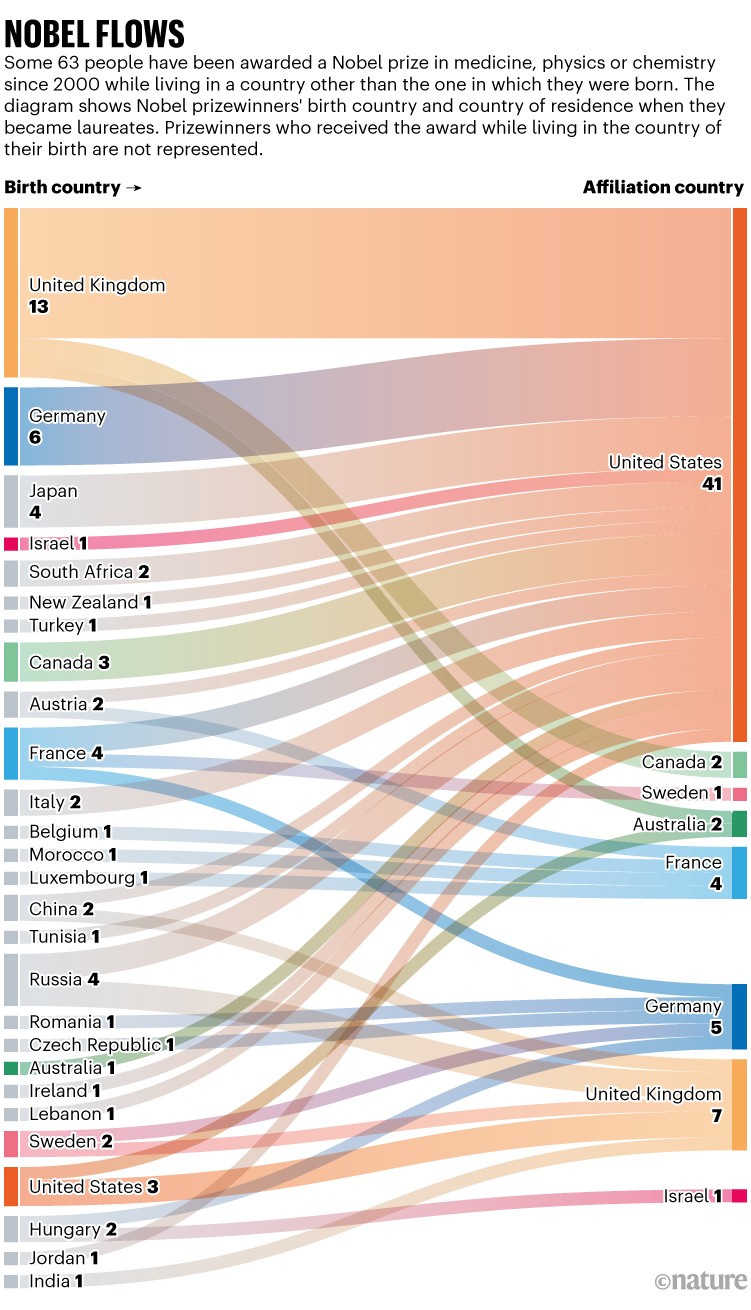

Of the 202 Nobel laureates who have been awarded prizes in physics, chemistry and medicine this century, less than 70% hail from the country in which they were awarded their prize. The remaining 63 laureates left their country of birth before winning a Nobel prize, sometimes crossing international borders more than once, a Nature analysis shows (see ‘Nobel flows’).

Among the Nobel prizewinners who emigrated to other countries are two of three chemistry winners announced on Wednesday. Richard Robson was born in the United Kingdom but now lives in Australia. And Omar Yaghi, who is now a US resident, became the first Jordanian-born Nobel laureate in science. Two of the three physics winners for 2025 are also immigrants: Michel Devoret was born in France and John Clarke in the United Kingdom, but both are US residents.

Source: nobelprize.org

Immigrants have long played an important part on the Nobel stage, including illustrious scientists such as Albert Einstein, who moved from his birthplace in Germany to Switzerland (and later to the United States), and Marie Curie, who left her native Poland to work in France. That’s because the most fruitful scientific opportunities — the best training, equipment and research communities — are scattered across the globe. “Talent can be born anywhere, but opportunities are not,” says Ina Ganguli, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “I think that’s the reason we see so many foreign Nobel laureates.”

The new analysis comes as the international flow of scientists and students faces growing obstacles. In the United States, for example, rampant grant cuts and stricter immigration policies implemented this year by the administration of President Donald Trump threaten a looming ‘brain drain’. Such restrictions “will slow the rate of highly novel research, period”, says Caroline Wagner, a specialist in science and technology policy at the Ohio State University in Columbus. Meanwhile, Australia has capped the number of international students that its institutions can enrol each year, and Japan proposed cutting financial support to graduate students from other countries.

Common destination

Among those who have already crossed borders is Andre Geim, a physicist at the University of Manchester, UK, and a 2010 physics laureate. Born in Russia to German parents, Geim says he “bounced around like a pinball” throughout his research career, holding positions in Russia, Denmark, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. “If you stay put your whole life, you miss half the game,” he says.

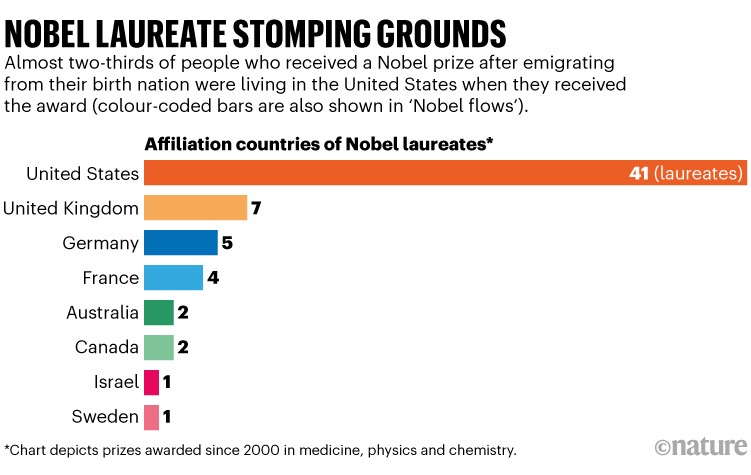

Of the 63 laureates who won the prize after moving out of their birth countries, 41 lived in the United States when their Nobel was awarded. After the Second World War, the United States became a global hub for science, Ganguli says. International researchers flocked there for its generous grants and top universities (see ‘Nobel laureate stomping grounds’). “What we have in the US is unique. It’s a destination for top students and scientists,” says Ganguli. The next most popular landing place was the United Kingdom, which was home to seven of the Nobel prizewinners who had emigrated by the time they got the fateful phone call from Stockholm.

Source: nobelprize.org

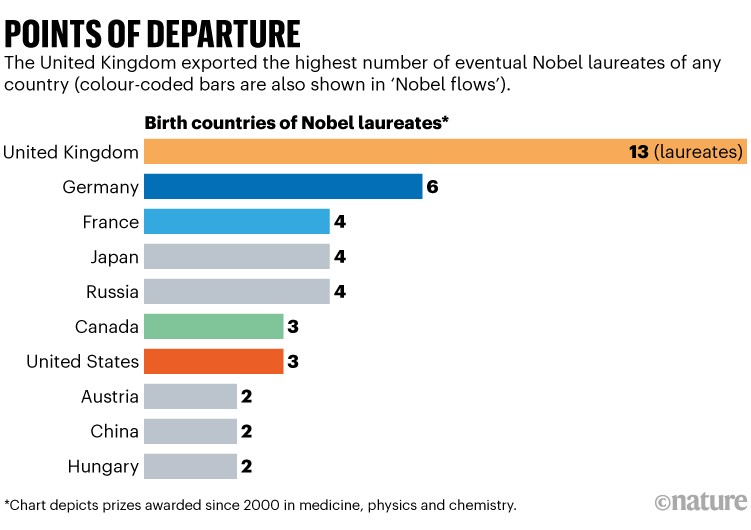

But, the United Kingdom also saw future prizewinners leave. Thirteen Nobel prizewinners who were born there won the prize while living elsewhere (see ‘Points of depature’), perhaps lured by higher salaries and more prestigious positions, Wagner says. Substantial numbers of future Nobel laureates also left Germany, with six expatriate prizewinners, as well as Japan, France and Russia, each with four expatriate laureates.

Source: nobelprize.org

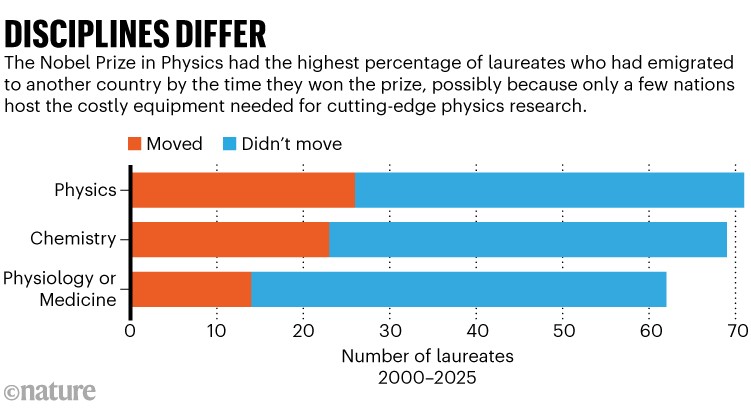

Among the science categories of the Nobel prizes, physics has the highest proportion of foreign-born laureates so far this century: 37% (see ‘Disciplines differ’). Trailing just behind is chemistry at 33%, and finally, medicine at 23%. Physics probably takes the lead because of its equipment-heavy nature, according to Wagner. The pricey colliders, reactors, lasers, detectors and telescopes that are needed for top-notch physics research reside mainly in a few leading nations. “Thus, the top research talent will likely go to places with top equipment. Medicine is not an equipment-heavy field, so it is easier to stay home,” Wagner says.

Source: nobelprize.org

Moving on

The future of immigration’s interplay with the Nobels is murky. Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom have all enacted restrictions that have reduced the number of university students from abroad. The Trump administration has slashed billions of dollars in scientific research grants so far this year. And a new US policy charges US$100,000 per application for an H-1B visa, which some foreign-born researchers rely on to work in the United States.

Already, international researchers are making moves to leave the United States, with other nations ready to woo them. France, South Korea and Canada have set up programmes to attract US researchers with awards and scholarships, for example. The European Research Council, which funds research in the European Union, is offering as much as €2 million ($2.3 million) to scientists who move their laboratories to the EU, with the goal of helping those moving from the United States.