Sample sizes

The sample sizes were not statistically determined before the experiments. Rather, the group sizes were on the basis of published literature for the type of manipulation (chemogenetics, site-specific genetic knockout and pharmacology) and measured outcome (such as pain behaviours) published in the field and/or by the authors involved2,28,64,66. The sample sizes for all experiments are included in the figure legends.

Data exclusions

For all imaging and behavioural studies, virus-injected animals with either little or no evidence of viral transduction and/or incorrect viral targeting were excluded from any final analyses. No other mice or data points were excluded across analyses.

Replication

For many of the behavioural studies, several cohorts were used owing to the large number of animals in the final group sizes. All behaviour results were consistent and replicated across cohorts. Individual data points or lines were included, indicating consistent trends across many mice in each behavioural study.

Blinding

Mice were randomly assigned into control or experimental groups to the best of the experimenter’s abilities, with counterbalancing for age and sex as needed. In most of the included studies, the experimental and control groups differed only in the type of virus infused intracranially. The surgical protocol for all mice was identical in the amount, wait time and location of the intracranial injection. Each surgery day was randomly assigned as a control or experimental surgery date, and the corresponding mice from the predetermined groups underwent surgery on that day. GRIN lens and fibre placements and viral spread maps were included in the supplement to demonstrate the similarity of the injection protocol and outcome. Once the experimental and control groups were formed to comprise the study cohort of mice, the cohort underwent all behavioural testing concurrently, and experimenters were blinded. After the analyses were completed, the experimenters were unblinded.

Animals

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania and performed in accordance with the US National Institutes of Health guidelines. Male and female mice aged 2–5 months were housed two to five per cage and maintained on a 12-h reverse light–dark cycle in a temperature-controlled and humidity-controlled environment. All experiments were performed during the dark cycle. The mice had ad libitum food and water access throughout the experiments. For behavioural, anatomical and transcriptomic experiments, we used Fos–FOS–2A–iCreERT2 or ‘TRAP2’ mice (Fostm2.1(icre/ERT2)Luo)Luo; The Jackson Laboratory; stock no. 030323)69 bred to homozygosity, C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory; stock no. 000664), Oprm1Cre/Cre mice (B6.Cg–Oprm1tm1.1(cre/GFP)Rpa/J; The Jackson Laboratory; stock no. 035574) and Oprm1fl/fl mice (B6;129–Oprm1tm1.1Cgrf/KffJ; The Jackson Laboratory; stock no. 030074). Further anatomical experiments used TRAP2 mice crossed with Ai9 (B6.Cg–Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J; The Jackson Laboratory; stock no. 007909) reporter mice that express a tdTomato fluorophore in a Cre-dependent manner.

Mouse μ-opioid receptor promoter

MORp2 is a 1.5-kb segment selected and amplified from mouse genomic DNA using cgcacgcgtgagaacatatggttggacaaaattc and ggcaccggtggaagggagggagcatgggctgtgag as the 5′ and 3′ end primers, respectively. All MORp plasmids were constructed on an AAV backbone by inserting either the MORp ahead of the gene of interest (iC++–eYFP) using M1uI and AgeI restriction sites. Every plasmid was sequence verified. Next, all AAVs were produced at the Stanford Neuroscience Gene Vector and Virus Core. Genomic titre was determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) of the WPRE element. All viruses were tested in cultured neurons for fluorescence expression before use in vivo.

Viral vectors

All viral vectors were either purchased from Addgene or custom designed and packaged by the authors as indicated. All AAVs were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use. The following viral vectors were used (titre in viral genomes (vg) per millilitre; volume in nanolitre; total dose in viral genomes; source): AAV9–hSyn–HI–eGFP–Cre–wpre–SV40 (5.44 × 1011 vg ml−1; 400 nl; 2.18 × 108 vg; Addgene 105540-AAV9), AAV9–hSyn–GFP (1.90 × 1011 vg ml−1; 400 nl; 7.60 × 107 vg; Addgene 50465-AAV9), AAVDJ–hSyn1–DIO–mCh–2A–MOR (1.13 × 1012 vg ml−1; 500 nl; 5.65 × 108 vg; custom from Banghart Lab), AAV5–hSyn–DIO–EGFP (1.30 × 1012 vg ml−1; 500 nl; 6.50 × 108 vg; Addgene 50457-AAV5), AAV9–hSyn–jGCaMP8m–WPRE (1.90 × 1012 vg ml−1; 800 nl; 1.52 × 109 vg; Addgene 162375-AAV9), AAV1–mMORp–hM4Di–mCherry (1.17 × 1012 vg ml−1; 500 nl; 5.85 × 108 vg; custom from Deisseroth Lab), AAV1–mMORp–eYFP (1.00 × 1012 vg ml−1; 500 nl; 5.00 × 108 vg; custom from Deisseroth Lab), AAV1–mMORp–Flpo (9.21 × 1011 vg ml−1; 400 nl; 3.68 × 108 vg (co-injected with Con/Fon–hM4D(Gi)); custom from Deisseroth Lab), AAV5–nEF–Con/Fon–hM4D(Gi)–mCherry (7.40 × 1012 vg ml−1; 400 nl; 2.96 × 109 vg (co-injected with mMORp–FlpO); custom from Deisseroth Lab) and AAV1–mMORp–DIO–iC++–eYFP (1.35 × 1012 vg ml−1; 400 nl; 5.40 × 108 vg; custom from Deisseroth Lab).

Stereotaxic surgery

Adult mice (approximately 8 weeks of age) were anaesthetized with isoflurane gas in oxygen (initial dose, 5%; maintenance dose, 1.5%) and fitted into World Precision Instruments or Kopf stereotaxic frames for all surgical procedures. NanoFil Hamilton syringes (10 µl; World Precision Instruments) with 33G beveled needles were used to intracranially infuse AAVs into the ACC. The following coordinates were used on the basis of the Paxinos mouse brain atlas to target these regions of interest (ROI): ACC (bregma: anterior–posterior, +1.50 mm; medial–lateral, ±0.3 mm; dorsal–ventral, −1.5 mm). The mice were given a 3-week to 8-week recovery period to allow ample time for viral diffusion and transduction to occur. For all surgical procedures in mice, meloxicam (5 mg kg−1) was administered subcutaneously at the start of the surgery, and a single 0.25-ml injection of sterile saline was provided upon completion. All mice were monitored and given meloxicam for up to 3 days following surgical procedures.

Chronic neuropathic pain model

As described previously65, to induce a chronic pain state, we used a modified version of the SNI model of neuropathic pain. This model entails surgical section of two of the sciatic nerve branches (common peroneal and tibial branches) while sparing the third (sural branch). Following SNI, the receptive field of the lateral aspect of the hindpaw skin (innervated by the sural nerve) displays hypersensitivity to tactile and cool stimuli, eliciting pathological reflexive and affective–motivational behaviours (allodynia). To perform this peripheral nerve injury procedure, anaesthesia was induced and maintained throughout surgery with isoflurane (4% induction; 1.5% maintenance in oxygen). The left leg and/or hindleg was shaved and wiped clean with alcohol and Betadine. We made a 1-cm incision in the skin of the mid-dorsal thigh, approximately where the sciatic nerve trifurcates. The biceps femoris and semimembranosus muscles were gently separated from one another with blunt scissors, thereby creating a less than 1-cm opening between the muscle groups to expose the common peroneal, tibial and sural branches of the sciatic nerve. Next, approximately 2 mm of both the common peroneal and tibial nerves were transected and removed, without suturing and with care not to distend the sural nerve. The leg muscles were left unsutured, and the skin was closed with tissue adhesive (3M Vetbond), followed by a Betadine application. During recovery from surgery, the mice were placed under a heat lamp until awake and achieved normal balanced movement. The mice were then returned to their home cages and closely monitored for well-being over the following 3 days.

Targeting Recombination in Active Populations protocols

PainTRAP

PainTRAP induction was performed as previously described65. We habituated mice to a testing room for two to three consecutive days. During these habituation days, no nociceptive stimuli were delivered, and no baseline thresholds were measured (the mice were naive to pain experience before the Targeting Recombination in Active Populations (TRAP) procedure). We placed individual mice in red plastic cylinders (approximately 9 cm in diameter), with a red lid, positioned on a raised perforated and flat metal platform (61 cm × 26 cm). The experimenters remained in the testing room for 30 min to allow habituation. This was done to mitigate potential alterations to the animals’ stress and endogenous antinociception levels. To execute the TRAP procedure, we placed the mice in their habituated cylinder for 30 min, after which a 55 °C water droplet was applied to the central–lateral plantar pad of the left hindpaw once every 30 s for 10 min. Following the water stimulations, the mice remained in the cylinder for an extra 60 min before subcutaneous injection of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (40 mg kg−1 in vehicle). After the injection, the mice remained in the cylinder for an extra 4 h to match the temporal profile for c-FOS expression, at which time the mice were returned to their home cages.

Home-cageTRAP

Home-cageTRAP induction was performed without habituation. At least 2 h into the dark cycle, mice were gently removed from their home cages. The mice were then injected with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (40 mg kg−1 in vehicle; subcutaneous) and returned to their home cages.

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were anaesthetized using Fatal-Plus (Vortech) and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M PBS, followed by 10% normal buffered formalin (NBF) solution (Sigma; HT501128). Brains were quickly removed and post-fixed in 10% NBF for 24 h at 4 °C and then cryo-protected in a 30% sucrose solution prepared in 0.1 M PBS until sinking to the bottom of their storage tube (approximately 48 h). The brains were then frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound (Thermo Fisher Scientific), coronally sectioned on a cryostat (CM3050S; Leica Biosystems) at 30 μm or 50 μm, and the sections were stored in 0.1 M PBS. Floating sections were permeabilized in a solution of 0.1 M PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-T) for 30 min at room temperature and then blocked in a solution of 0.3% PBS-T and 5% normal donkey serum (NDS) for 2 h before being incubated with primary antibodies (chicken anti-GFP (1:1,000; Abcam; ab13970), guinea pig anti-FOS (1:1,000; Synaptic Systems; 226308), rabbit anti-FOS (1:1,000; Synaptic Systems; 226008) and rabbit anti-DsRed (1:1,000; Takara Bio; 632496)), prepared in a 0.3% PBS-T and 5% NDS solution for approximately 16 h at room temperature. Following washing three times for 10 min in PBS-T, secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-rabbit (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific; A31573), Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-chicken (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch; 703-545-155), Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific; A31572) and Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-guinea pig (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch; 706-605-148), prepared in a solution of 0.3% PBS-T and 5% NDS, were applied for approximately 2 h at room temperature, after which the sections were washed again three times for 5 min in PBS-T and then again three times for 10 min in PBS-T, and then counterstained in a solution of 0.1 M PBS containing DAPI (1:10,000; Sigma; D9542). Fully stained sections were mounted onto Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific) and allowed to dry and adhere to the slides before being mounted with Fluoromount-G Mounting Medium (Invitrogen; 00-4958-02) and coverslipped.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

Animals were anaesthetized using isoflurane gas in oxygen, and the brains were quickly removed and fresh frozen in O.C.T. using Super Friendly Freeze-It Spray (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The brains were stored at −80 °C until cut on a cryostat to produce 16-μm coronal sections of the ACC. Sections were adhered to Superfrost Plus microscope slides and immediately refrozen before being stored at −80 °C. Following the manufacturer’s protocol for fresh frozen tissue for the RNAscope v.2 manual assay (Advanced Cell Diagnostics), slides were fixed for 15 min in ice-cold 10% NBF and then dehydrated in a sequence of ethanol serial dilutions (50%, 70% and 100%). The slides were briefly air-dried, and then a hydrophobic barrier was drawn around the tissue sections using a PAP Pen (Vector Labs). The slides were then incubated with hydrogen peroxide solution for 10 min, washed in distilled water and then treated with the Protease IV solution for 30 min at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Following protease treatment, C1 and C2 complementary DNA (cDNA) probe mixtures specific for mouse tissue were prepared at a dilution of 50:1, respectively, using the following probes from Advanced Cell Diagnostics: Oprm1 (C1; 315841), Slc17a7 (C3; 416631) and Fos (C4; 316921). Sections were incubated with cDNA probes (2 h) and then underwent a series of signal amplification steps using FL v.2 Amp 1 (30 min), FL v.2 Amp 2 (30 min) and FL v.2 Amp 3 (15 min). A 2-min wash in 1x RNAscope wash buffer was performed between each step, and all incubation steps with probes and amplification reagents were performed using a HybEZ oven (ACD Bio) at 40 °C. The sections then underwent fluorophore staining through treatment with a series of TSA Plus HRP solutions and Opal 520, 570 and 620 fluorescent dyes (1:5,000; Akoya Biosciences; FP1487001KT and FP1495001KT). All HRP solutions (C1 and C2) were applied for 15 min and Opal dyes for 30 min at 40 °C, with an extra HRP blocker solution added between each iteration of this process (15 min at 40 °C) and rinsing of sections between all steps with the wash buffer. Finally, the sections were stained for DAPI using the reagent provided in the Fluorescent Multiplex Kit. Following DAPI staining, the sections were mounted and coverslipped using Fluoromount-G mounting medium and left to dry overnight in a cool, dark place. The sections from all mice were collected in pairs using one section for incubation with the cDNA probes and another for incubation with a probe for bacterial mRNA (dapB; ACD Bio; 310043) to serve as a negative control.

Imaging and quantification

All tissue was imaged on a KEYENCE BZ-X all-in-one fluorescence microscope at 48-bit resolution using the following objectives: PlanApo-λ ×4, PlanApo-λ ×20 and PlanApo-λ ×40. All image processing before quantification was performed with the KEYENCE BZ-X analyzer software (v.1.4.0.1). Quantification of neurons expressing fluorophores was performed through manual counting of TIFF images in Photoshop (Adobe, 2021) using the Count function or HALO software (Indica Labs), which is a validated tool for automatic quantification of fluorescently labelled neurons in brain tissue70,71,72. Counts were made using ×20 magnified z-stack images of designated ROI. For axon density quantification, immunohistochemistry was performed to amplify the signal and visualize ACC axons throughout the brain in 50-μm tissue free-floating slices as described above. Areas with dense axon innervation were identified using ×4 imaging. Areas implicated in emotion and nociception were selected for further ×20 imaging with z stacks. These ROI were initially visualized at ×20 to determine the region with the highest fluorescence. Exposures for FITC and CY3 were adjusted to avoid overexposed pixels for the brightest area. This exposure was kept consistent for all slices for an individual mouse. For an individual ROI, one slice per mouse was included.

We used HALO software for all quantifications. One representative 16-μm slice containing ACC (selected from 1.1–1.3 mm anterior of bregma) was quantified per mouse using HALO Image Analysis software (Indica Labs). The borders for left and right ACC, Cg1, Cg2, L1, L2/3, L5, L6a and L6b were hand-drawn as individual annotation layers using the Allen Brain Reference Atlas as a guide. Slices were visually inspected for damage, dust or other debris and bound probe, and these areas were manually excluded from their respective annotation layers. Co-localization of nuclei (DAPI) with Oprm1, Fos and Vglut mRNA puncta was automatically quantified using the fluorescence in situ hybridization module (v.3.2.3) and traditional nuclear segmentation. Setting parameters were optimized by comparing performance across six slices, randomly selected across experimental groups, and confirming proper detection by visual inspection. Identical parameters were applied across all slices in the dataset.

Drugs and delivery

For chemogenetic studies, water-soluble DCZ dihydrochloride (Hello Bio; HB9126) was delivered intraperitoneally at a dose of 0.3 mg kg−1 body weight. For Oprm1 knockout, re-expression and miniscope testing, morphine sulfate (Hikma) was delivered acutely through intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 0.5 mg kg−1 body weight.

Human-scored behavioural tests

All experiments were performed during the dark phase of the cycle (0930 hours to 1830 hours). Group-housed and singly housed mice were allowed a 1-week to 2-week acclimation period to housing conditions in the vivarium before starting any behavioural testing. Additionally, 3–5 days before the start of testing, the mice were handled daily to help reduce experimenter-induced stress. On test days, the mice were brought into procedure rooms approximately 1 h before the start of any experiment to allow for acclimatization to the environment. They were provided food and water ad libitum during this period. For multi-day testing conducted in the same procedure rooms, the animals were transferred into individual ‘home away from home’ secondary cages approximately 1 h before the start of testing and were only returned to their home cages at the end of the test day. Testing and acclimatization procedures were conducted under red light conditions (less than 10 lux), with minimal exposure to bright light to avoid disruption of the reverse light cycle schedule. Equipment used during testing was cleaned with 70% ethanol solution before starting and between each behavioural trial to eliminate odors and scents.

Sensory testing for pain affective–motivational and nociceptive reflex behavioural assays

To evaluate responses to acute stimuli, animals were placed in transparent red cylinders placed on top of a metal hexagonal-mesh floored platform. Stimuli were applied to the underside of the left plantar hindpaw. This process was repeated for a total of ten applications, with each droplet applied at a 1-min interval. The animals were continuously recorded using a web camera positioned to face the front of the cylinder in which the animal was housed, and the time spent attending to the affected paw was quantified for up to 30 s after the stimulation.

To evaluate mechanical reflexive sensitivity, we used a logarithmically increasing set of eight von Frey filaments (Stoelting), ranging in gram force from 0.07 g to 6.0 g. These filaments were applied perpendicular to the plantar hindpaw with sufficient force to cause a slight bending of the filament. A positive response was characterized as a rapid withdrawal of the paw away from the stimulus within 4 s. Using the up-and-down statistical method, 50% withdrawal mechanical threshold scores were calculated for each mouse and then averaged across the experimental groups65. To evaluate affective–motivational responses evoked by thermal stimulation65, we applied either a single unilateral 55 °C drop of water or acetone (evaporative cooling) to the left hindpaw, and the duration of attending behaviour was collected for up to 30 s after the stimulation. Response to the noxious stimulus was also tested following acute intraperitoneal administration of morphine (0.5 mg kg−1 body weight) or DCZ (0.3 mg kg−1 body weight). After injection, the animals were returned to their home away from home cages for 30 min to allow complete absorption of the drug. Hot-water hindpaw stimulation testing was conducted in the naive condition as described above.

Additionally, we used an inescapable hotplate set to 50 °C. The computer-controlled hotplate (6.5 in. × 6.5 in. floor; Bioseb) was surrounded by a 15-in.-high clear plastic chamber, and two web cameras were positioned at the front or side of the chamber to continuously record animals to use for post hoc behavioural analysis. For the tests conducted for chemogenetic or pharmacology studies, mice were administered morphine or DCZ 30 min before behavioural testing to allow for complete absorption of the drug and previous sensory testing73. The mice were gently placed in the centre of the hotplate floor and removed after 60 s.

Maximum possible analgesia effect calculation

The maximum possible analgesia (%MPA) metric quantifies how much a pain-related behaviour is reduced following drug administration, relative to both the animal’s baseline response and the maximum behavioural response for that assay. This normalization enables meaningful comparisons across animals with different baseline sensitivity levels. It is calculated as

$$100\,\times \,\frac\mathrmpost-\mathrmdrug\,\mathrmbehaviour-\mathrmbaseline\,\mathrmbehaviour\,\mathrmmaximum\,\mathrmbehaviour-\mathrmbaseline\,\mathrmbehaviour\,$$

This normalization allows for comparisons across animals with different baseline response levels. For example, in the von Frey up-and-down test, the maximum behaviour for withdrawal threshold is 6.0 g (the highest filament force that would indicate the maximal amount of analgesia post-drug), and the minimum threshold is 0.007 g. For affective–motivational responses to thermal stimuli, behavioural responses such as attending or escape are measured over a 60-s window. Here the minimum behavioural response time is 0.0 s, and the maximum behaviour is capped at 30 s (trial duration). In this case, maximum analgesia corresponds to no response to the noxious stimulus; thus, the maximum behaviour in the %MPA formula is 0.0 s. This approach ensures consistent scaling of behavioural change across experiments and conditions. This formula provides a normalized score ranging from 0% (no analgesia) to 100% (complete analgesia). The definition of ‘maximum behaviour’ depends on the behavioural test and reflects the highest measurable response in the absence of any analgesia, whereas the ‘baseline behaviour’ is typically the pre-drug measurement for that animal. This approach ensures consistent and interpretable scaling of drug-induced behavioural changes across assays and experimental conditions.

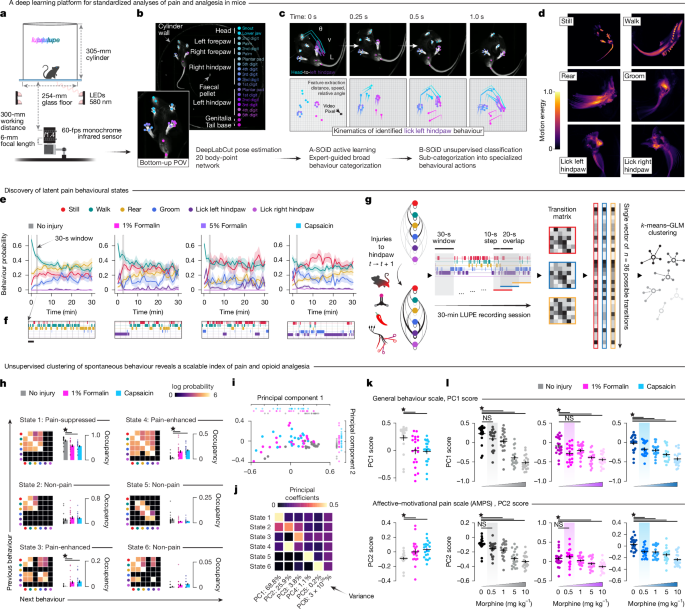

LUPE acquisition and analysis software

Video acquisition

Behavioural videos were recorded using a Basler ace UacA2040-120um camera at a fixed resolution of 768 (width) by 770 (height) pixels. Imaging parameters were standardized, with gain set to 10.0 dB and gamma at 2.0. Exposure mode was timed with an exposure duration of 1,550 ms per frame, triggered at the start of each frame. Videos were captured at a consistent frame rate of 60 frames per second at maximum quality, with a recording buffer size of 128 frames. Frames were stored every 16 ms to ensure high temporal resolution of behavioural sequences.

Pose estimation through DeepLabCut

Assigning 2D markerless pose estimation of mice within LUPE was achieved through the DLC program (v.2.3.5-8). DLC was favoured for this purpose because of its ability to track body points at high confidence when animals perform diverse behaviours and to accurately report if a body part is visible in a given frame. Its extensive toolkit, documentation and forums allow flexible user input and manipulation when creating models.

The body points considered for assigning pose in the LUPE–DLC model were based on the clarity and frequency of appearance, involvement in behaviour sequences and prospective analyses performed. As such, 20 body points were included in the LUPE pose estimation network built in DLC: snout, upper mouth, middle forepaw digit and palm of left and right forepaws, all digits and palm of left and right hindpaws, genital region and tail base.

The model was trained iteratively 17 times for up to 350,000 iterations per training when loss and learning rate plateaued. The network architecture and augmentation method chosen were ResNet-50 and imgaug, respectively. The model was trained on 95% of the dataset, with the remaining 5% reserved for testing and evaluation. In the final training iteration, the mean average Euclidean errors between the manual labels and those predicted by the model were 2.2 pixels (0.073 cm) for the training dataset error and 2.33 pixels (0.077 cm) for the test dataset error.

Frames for labelling were manually extracted, targeting specific behavioural sequences and individual frames not accurately or confidently labelled by the model. After each training, frames for data input were added as needed for accuracy and confidence to label videos trained on and new videos analysed through LUPE not trained in the model. The total number of frames labelled was 14,554, with 10,825 (74.38%) and 3,729 (25.62%) frames coming from male and female video data files, respectively. Frames were extracted from 169 unique mouse video files comprising 133 males (78.69%) and 36 females (21.31%). The behavioural assays chosen for recording and model input captured different experimental paradigms and chemically evoked manipulations. From this, the model was able to assign pose data points with high accuracy and confidence for both male and female mouse video data from a variety of behavioural data.

The male video dataset included subcutaneous saline injection response (210; 1.94%), subcutaneous morphine 10 mg kg−1 response (1,105; 10.21%), left hindpaw intraplantar capsaicin response (666; 6.15%), left hindpaw intraplantar 1% formalin (960; 8.87%), left hindpaw intraplantar 5% formalin (1,271; 11.74%), habituation to LUPE chamber (720; 6.65%), formalin left hindpaw intraplantar injection (829; 7.66%), formalin right hindpaw intraplantar injection (719; 6.64%), formalin cheek injection (472; 4.36%), SNI left hindpaw injury day 0 (170; 1.57%), SNI left hindpaw injury day 3 (508; 4.69%), SNI left hindpaw injury day 7 (380; 3.51%), SNI left hindpaw injury day 21 (255; 2.36%), SNI right hindpaw injury day 0 (652; 6.02%), SNI right hindpaw injury day 3 (508; 4.69%), SNI right hindpaw injury day 7 (510; 4.71%), SNI right hindpaw injury day 21 (254; 2.35%) and naloxone precipitated morphine withdrawal (636; 5.88%).

The female video dataset included subcutaneous morphine 10 mg kg−1 response (133; 3.57%), habituation to LUPE chamber (320; 8.59%), formalin left hindpaw intraplantar injection (148; 3.97), formalin right hindpaw intraplantar injection (150; 4.02%), SNI left hindpaw injury day 0 (1,050; 28.17%), SNI left hindpaw injury day 3 (450; 12.07%), SNI left hindpaw injury day 7 (350; 9.39%), SNI right hindpaw injury day 0 (826; 22.16%), SNI right hindpaw injury day 3 (150; 4.02%) and SNI right hindpaw injury day 7 (150; 4.02%).

Behaviour classification through A-SOiD/B-SOiD

We trained a random forest classifier to predict five different behaviours (still, walking, rearing, grooming and licking hindpaw) given the pose estimation of the previously described 20 body parts. This supervised classifier was refined using an active learning approach over 27 iterations, with a total of 51,377 frames: still (11,599), walking (12,809), rearing (7,270), grooming (12,719) and licking hindpaw (6,971). Upon reaching an average f1 score of 93.5% across the five classes, we predicted all existing pose files and segmented licking hindpaw into licking left hindpaw and licking right hindpaw because they were clearly dissociable. After splitting the laterality of licking hindpaw, we retrained the random forest classifier to expand its classification from five classes to six classes. The final average f1 score across the six classes was 94.3%.

LUPE analyses

Once the model was trained, we predicted all the behavioural data in this study using the same random forest classifier model. Owing to the nature of intermittent pose estimation noise, we decided to smooth the output behaviour, considering only continuous bouts of 200 ms or longer.

To analyse behaviour ratio over time (Fig. 1), we calculated per-minute counts for each behaviour and normalized them by the total number of frames. This quantification allowed us to track when a particular behaviour occurred during each session. To explore variability across animals, we plotted the mean ± s.e.m.

To analyse the distance travelled, one body point high in confidence for pose detection and always present in behavioural sequences was chosen as the tail base to calculate the Euclidean distance between consecutive frames of the tail base position. This was calculated by subtracting the x and y coordinates of the tail base between consecutive frames and then calculating the Euclidean norm of the resulting vector. The distance calculated in pixels was then converted to centimetres using a conversion factor of 0.0330828 cm per pixel. This conversion factor is unique to the aspect ratio of our frames and resolution of the video data. To explore the variability across animals, we plotted the mean ± s.e.m.

Heat maps of the distance travelled were generated by constructing a 2D histogram of the tail base x and y coordinates. The code functions by binning the pose data points into a specified number of bins (50 in this case) along each x-coordinate and y-coordinate range. The ‘counts’ collected represent the frequency of occurrences in the 2D histogram that fall in each bin representing a range of x and y coordinates.

Identification of behaviour states and AMPS

Behavioural state identification

LUPE behaviour scores recorded at 60 Hz from all male and female animals across all pain models used in this study (uninjured mice, 2% capsaicin, 1% and 5% formalin and SNI) were downsampled to 20 Hz by taking the mode of every three frames. Transition matrices were generated between behaviours, with values expressed as the percentage of all frames, in which behaviour bx at time t was followed by behaviour by at time t + 1.The transition matrices were taken over 30-s windows sliding by 10-s increments within animals to avoid missing transitions. The window size was chosen in line with empirical findings that showed spontaneous bouts of intense subjective pain under chronic pain conditions lasting 22.5 ± 22.1 s (mean; s.d.)74. The transition matrices were transformed into single rows such that each transition matrix became a single vector of probabilities with 36 possible transitions: P(stillt+1|stillt), P(walkt+1|stillt), P(reart+1|stillt)…P(right lickt+1|right lickt). These probability vectors were then stacked to create a matrix of 215,760 observations (3,596 observations for 60 animals) by 36 transitions. These observations were clustered using 100-fold cross-validated k-means, in which the silhouette and elbow methods robustly converged at six clusters over 100 iterations. Each of six centroids thus defined a single behavioural state that could be expressed as reconstructed transition matrices.

Behavioural state classification

To classify each time point as one of six behavioural states, the same process as described above was repeated to generate smoothed transition matrices over time for each animal. At each time point, the Euclidean distance was calculated between its given transition matrix and each model centroid. The state at that time point was chosen to minimize the distance from the true transition matrix and the model centroid. Model fit for each animal in each session is thus expressed as the mean distance from the nearest centroid to its real transition matrix over the session. As distance approaches 0, the model approaches perfect fit. Transition matrices randomly shuffled over probabilities show that, at chance, model fit converges between 2 arbitrary units (a.u.) and 3 a.u., whereas true model fit ranges between 0 a.u. and 1.5 a.u., indicating genuine discovery of behavioural structure at a timescale of seconds to minutes.

Behaviour state model validation

To ensure that states were not trivially dependent on the occurrence or absence of a single behaviour, states were classified after systematically removing each behaviour from the dataset. Model fit and the percentage of observations matching the original classifications were compared with those of the shuffled dataset.

Pain scale

To distill behavioural states into a single index of pain, PCA was performed on the state distributions of each animal in the uninjured, capsaicin and formalin experiments that received 0 mg kg−1 of morphine. Each animal was described by the fraction time spent in each state, yielding a six-dimensional dataset. The scores of each animal along the first two PCs were considered. To yield scores for animals in every other experiment and condition, state distributions were projected into this PC state by subtracting the mean of the original dataset and matrix multiplying by the coefficients defining the PC space. We predetermined that the PC that scales oppositely with pain condition and analgesia would be designated the AMPS ‘pain scale’. PC2 met this requirement.

Within-state behaviour dynamics

To assess temporal dynamics of behaviours over states, the binarized behaviour classification vectors (behaviour of interest, 1; all others, 0) over the course of a given bout of a state were resampled to be 100 steps long. These vectors were pooled across bouts and animals in a given condition and averaged to yield behavioural probability as a fraction of time completed in state. The fraction of time remaining in state with respect to a behaviour occurrence was calculated by subtracting the absolute time of the behaviour from the absolute end time of that state bout and dividing by the duration.

For simulated behaviour dynamics, 100 Markov simulations of behaviours on the basis of the state 4 centroid transition matrix were produced over the course of a state for each possible initial condition (stillness, walking, rearing, grooming and licking) and allowed to proceed for the empirically determined average number of time steps state 4 lasts (600) before undergoing the same procedure.

In vivo calcium imaging

Miniscope surgery

For miniscope studies, all mice underwent an initial intracranial injection using previously described methods, followed 2 weeks later by a GRIN lens implant surgery. During the intracranial injection surgery, 800 nl of AAV9–hSyn–jGCaMP8m at a titre of 1.9 × 1012 (Addgene virus no. 162375) was infused into the right ACC (anterior–posterior, +1.5; medial–lateral, 0.3; dorsal–ventral, −1.5 mm). Two weeks later, GRIN lens implantation surgeries were performed following the same protocol up to the craniotomy step. A 1-mm craniotomy was made by slowly widening the craniotomy with a drill. The dura was peeled back using microscissors, sharp forceps and curved forceps. The craniotomy was regularly flushed with saline, and gel foam was applied to absorb blood. An Inscopix Pro-View Integrated GRIN lens and baseplate system was attached to the miniscope and stereotax. Using the Inscopix stereotax attachment, the lens was slowly lowered into a position over the injection site. The final dorsal–ventral coordinate was determined by assessing the view through the miniscope stream. If tissue architecture could be observed in full focus with light fluctuations suggesting the presence of GCaMP-expressing cells, the lens was implanted at that coordinate (−0.6 mm to −0.3 mm dorsal–ventral). The GRIN lens/baseplate system was secured to the skull with Metabond, followed by dental cement. After surgery, the mice were singly housed and injected with meloxicam for three consecutive days during recovery.

Miniscope data collection for acute capsaicin

Miniscope neural activity and associated behaviour data were collected over 2 days (baseline/capsaicin (test day 1) and morphine/capsaicin (test day 2)), with 2 weeks between test days. On each day, the Inscopix nVista3.0 miniscope was first affixed on the mouse, and ideal focus was determined on the basis of the field of view. Imaging parameters (power, 0.7 mW mm−2; gain, 2) were held consistent across all mice and test days. The mice were injected with saline (test day 1) or 0.5 mg kg−1 of morphine (test day 2) and placed in LUPE. Five minutes later, miniscope and LUPE recordings were started and continued uninterrupted for 20 min. The recording was then stopped for 5 min to reduce photobleaching risk. Next, the mice were injected with 2-μg capsaicin (Hello Bio; HB1179) in the left hindpaw (both test days) using a Hamilton syringe affixed with a 30G needle and placed in LUPE. Both miniscope and LUPE recordings were immediately restarted after and continued for 30 min.

Miniscope data collection for chronic neuropathic pain

The behaviour and neural activity of mice were recorded eight times before, during and after the onset of SNI. The mice were tested at baseline (1 day before SNI) and then 1 h, 1 day, 3 days, 1 week, 2 weeks and 3 weeks post-SNI. One day after the 3-week testing session, the mice underwent another test day in which they were injected with 0.5 mg kg−1 of morphine 30 min before recording. Each testing day consisted of a 30-min LUPE recording. Ideal imaging parameters were determined on each day, and neural activity was aligned to LUPE behaviour tracking through a transistor–transistor logic pulse at the start of the recording session.

Miniscope data collection for pain and valence panels

Within 1 week after completion of the chronic neuropathic pain LUPE testing, mice underwent exposure to a panel of acute stimuli while neural activity was recorded. The animals were placed in transparent containers placed on top of a metal hexagonal-mesh floored platform. Stimuli were applied to the underside of the left plantar hindpaw. The animals were continuously recorded using two web cameras.

The stimuli were light touch (0.16 g von Frey filament), 30 °C water, pin prick (25G syringe needle), acetone and hot water (55 °C). Water and acetone stimuli were delivered using a needleless syringe, and a droplet of the liquid was applied. Five presentations of each stimulus were administered to the left hindpaw with 90 s between each presentation.

After the pain panel, the mice underwent 3 days of 20-min training for the valence panel, in which they learned to lick a 10% sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich S7903; diluted in water) droplet from a needleless syringe poked through the mesh of the metal rack. On the day of the panel, neural activity was recorded while they licked sucrose (approximately seven presentations), with at least 45 s between each presentation, and then the liquid in the syringe was switched to 0.06 mM quinine (Sigma-Aldrich Q1125; diluted in water). Quinine was presented until the mice licked at least five times. Finally, seven presentations of 55 °C water were applied to the left hindpaw. Both sucrose and quinine concentrations were adapted from ref. 65.

Calcium imaging preprocessing

Videos were downloaded from the Inscopix Data Acquisition Box and uploaded to the Inscopix Data Processing Software. Videos were spatially downsampled by a factor of 4 and spatial bandpass filtered between 0.005 and 0.500. The videos were then motion corrected with respect to their mean frame. Cells were identified and extracted using constrained non-negative matrix factorization for microendoscopic data (default parameters in the Inscopix implementation, except the minimum in-line pixel correlation is 0.7 and the minimum signal-to-noise ratio is 7.0) and deconvolved using second-order constrained spike deconvolution.

Spontaneous activity in neurons

Deconvolved activity in each neuron was z-scored. Peaks were identified using the findpeaks function in MATLAB with the argument ‘MinPeakProminence’ set to 1.

Neural encoding of behavioural probabilities

Categorical frame-by-frame vectors of behavioural values (still, walking, rearing, grooming, licking left hindpaw and licking right hindpaw) were downsampled from 60 Hz to 20 Hz to match sampling rates of neural recordings by taking the floor of the mode for within a sliding window of three frames. The probability of engaging in a behaviour as generated by this k-means–GLM model thus takes into account recent behaviour history and slowly evolving state of the animal. These higher-order measurements of behavioural state have been linked to neural activity previously75,76,77. To identify neurons encoding this higher-order index of behavioural state, a binomial GLM was trained to predict binarized probabilities of a given behaviour (thresholded at Pbehaviour = 0.5) from the PCs of the ACC activity explaining 80% of the variance in individual animals. Neurons with a coefficient greater than 1.5 z-score in the three most highly weighted PCs were classified as Pbehaviour-encoding neurons. Neurons that, on average, increased or decreased their activity within 500 ms following the onset of behaviour were classified as behaviour+ or behaviour− neurons, respectively.

Behaviour-evoked activity

To assess modulation of activity in these neurons by behaviour, peri-behavioural time histograms of neural activity were generated from 2 s before to 2 s after the start of each behaviour bout. To quantify, peri-behavioural time histograms were z-scored to the 1 s before behaviour onset, and areas under the curve were taken for each of the 2 s after the bout start. If a neuron was suppressed after behaviour onset, it was designated a behaviour-off neuron and vice versa for a behaviour-on neuron. Behavioural tuning curves were generated by taking the z-score of the activity of each population of encoding neurons during each scored behaviour. Selectivity of these neurons for a given behaviour was calculated by taking the d′ between their encoded behaviour and each other behaviour:

$$d^\prime =\frac\sqrt\frac\sigma 1+\sigma 22$$

Behaviour, sensory and state decoding

For behaviour and sensory decoding, a Fisher linear decoder was trained to predict each behaviour or sensory stimulus in a given session from the activity of all neurons. For state decoding, a support vector machine decoder was trained to predict whether animals were in a pain or non-pain state using the activity of lick-probability-encoding neurons. Each decoder for each animal and session underwent 100-fold cross-validation, training on a random 80% of the data each time and testing on 20%. Data were randomly subsampled to ensure an equal number of samples per class, thereby eliminating training bias. Decoders were also trained on randomly shuffled data as a control. Confusion matrices were generated, averaged over cross-validations and normalized by the true frequency of each behaviour in the test set. Significance was determined using a permutation test.

Identifying stimulus-active neurons

For pain and valence panels, the activity of each neuron from 0 s to 3 s after stimulus was compared with the activity from −3 s to −1 s before stimulus with a permutation test (false discovery rate (FDR) threshold P < 0.01).

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing

Nuclei preparation

A single punch of the right side of the basolateral amygdala measuring 2 mm in width and 1 mm in depth was used to prepare nuclei suspensions. Nuclei isolation was performed using the Minute Single Nucleus Isolation Kit designed for neuronal tissue/cells (BN-020; Invent Biotechnologies). In brief, the tissue was homogenized using a pestle in a 1.5-ml LoBind Eppendorf tube. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in 700 µl of cold lysis buffer and RNase inhibitor and incubated on ice for 5 min. The homogenate was then transferred to a filter within a collection tube and incubated at −20 °C for 8 min. Following this, the tubes were centrifuged at 13,000g for 30 s, the filter was discarded and the samples were centrifuged at 600g for 5 min. The resulting pellet underwent one wash with 200 µl of PBS + 5% bovine serum albumin and then resuspended in 60 µl of PBS + 1% bovine serum albumin. The concentration of nuclei in the final suspension was assessed by staining with Trypan Blue and counted using a haemocytometer. The suspension was diluted to an optimal concentration of 500–1,000 nuclei per microlitre.

Single-nucleus gene expression assay

Nuclei suspensions were used as input for the 10x Genomics 3′ gene expression assay (v.3.1), following manufacturerʼs protocols. A total of 20,000 nuclei were loaded into the 10x Genomics Chromium Controller, with the aim of recovering approximately 10,000–12,000 nuclei per sample. Subsequently, sequencing libraries were constructed, and unique dual-indexed libraries were pooled together at equimolar concentrations of 1.75 nM and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 using 28 cycles for read 1, 10 cycles for the i7 index, 10 cycles for the i5 index and 90 cycles for read 2.

Data analysis

Preprocessing of single-nucleus RNA sequencing data

Paired end sequencing reads were processed using 10x Genomics Cell Ranger v.5.0.1. Reads were aligned to the mm10 genome optimized for single-cell sequencing through a hybrid intronic read recovery approach78. In short, reads with valid barcodes were trimmed by template switching oligonucleotide sequence and aligned using STAR v.2.7.1 with MAPQ adjustment. Intronic reads were removed, and high-confidence mapped reads were filtered for multimapping and unique molecular identifier correction. Empty gel beads in emulsion were also removed as part of the pipeline. DESeq2 was used to compare expression at the 3-day, 3-week and 3-month time points to control animals for each cluster. Pseudobulked expression differences were assessed by performing Wald test, and a FDR of 0.05 was used to correct for multiple testing.

Clustering and comparison

Count matrices for each individual sample were converted to Seurat objects using Seurat 4.3, and nuclei were filtered with thresholds of greater than 200 minimum features and less than 5% mitochondrial reads. Initial dimensionality reduction and clustering were performed to enable removal of cell-free mRNA using SoupX79. SCTransform was used to normalize and scale expression data, and all samples were combined using the Seurat integration method. Putative doublets identified by DoubletFinder, as well as residual clusters with mixed cell-type markers or high mean unique molecular identifier, were removed. The cleaned dataset was clustered using the first 20 PCs at a resolution of 0.3. Cluster identity was determined by expression of known marker genes.

Modular activity scoring

Modular activity scores were calculated for all clusters using AddModuleScore with the list of the 25 putative IEGs (Arc, Bdnf, Cdkn1a, Dnajb5, Egr1, Egr2, Egr4, Fos, Fosb, Fosl2, Homer1, Junb, Nefm, Npas4, Nr4a1, Nr4a2, Nr4a3, Nrn1, Ntrk2, Rheb, Sgsm1, Syt4 and Vgf) against a control feature score of 5 (ref. 80).

Gene ontology analysis

Gene Ontology analysis was performed on differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified between uninjured and SNI conditions. To investigate the functional enrichment of genes upregulated in the SNI condition, we used SynGO (https://www.syngoportal.org/), a synapse-specific, evidence-based Gene Ontology annotation platform that provides curated information about synaptic genes and their roles in biological processes, molecular function and cellular localization. Gene symbols corresponding to upregulated DEGs were submitted to the SynGO web-based analysis tool. Enrichment analysis was performed against the background of all protein-coding human genes mapped to orthologous mouse genes using SynGO’s default statistical settings. We focused on enrichment within high-confidence, expert-curated Gene Ontology categories on the basis of experimental evidence. Overrepresentation testing was conducted with FDR correction, and enriched Gene Ontology terms were considered significant at FDR < 0.05. The analysis enabled functional interpretation of synaptic gene expression changes in chronic pain conditions, with particular attention to processes related to synaptic signalling, neurotransmitter transport and pre-synaptic or post-synaptic structural components.

Quantitative PCR

Cellular RNA was extracted with RNAZol (Sigma-Aldrich; R4533) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and cDNA was synthesized from 1-μg RNA (Applied Biosystems; 4374966). cDNA was diluted 1:10 and assessed for mRNA transcript levels by qPCR with SYBR Green Mix (Applied Biosystems; A25741) on a QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The oligonucleotide primer sequences for target and reference genes are as follows: mouse_GAPDH (forward: AACGACCCCTTCATTGACCT; reverse: TGGAAGATGGTGATGGGCTT), mouse_L30 (forward: ATGGTGGCCGCAAAGAAGACGAA; reverse: CCTCAAAGCTGGACAGTTGTTGGCA) and mouse_OPRM1 (forward: CTGCAAGAGTTGCATGGACAG; reverse: TCAGATGACATTCACCTGCCAA). Fold change in the target mRNA abundance was normalized by the reference gene GAPDH and calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method81.

Closed-loop, optogenetic real-time place preference and conditioned place preference

First, painTRAP2 mice injected with AAV1–MORp–DIO–iC++ and bilateral fibre-optic implants (200-µm diameter; 0.66 numerical aperture; 700-µm pitch between each fibre centre; Thorlabs), with SNI or no injury, were habituated for 30 min a day for 5 days in a holding cage. For basal place-preference measurements (pretest session), mice with attached patch cables were placed in a two-chamber acrylic box (60 × 25 × 30 cm3), with each side of the chamber measuring 30 × 25 cm2), at room temperature (approximately 23 °C) and under approximately 10 lux red light. Each chamber had different contextual pattern cues on the wall: one side had a black-and-white striped pattern and the other a dotted pattern. Mouse movements were recorded in real time using an overhead Basler top-view camera connected to EthoVision tracking software (Noldus), connected through a mini-I/O box to a 450-nm LED and pulse-wave generator (Prizmatix), for 30 min. Chamber preference times were quantified using EthoVision for the amount of time spent in each chamber. Using a biased design, on the basis of the quantified basal preference, the mice received LED stimulation in the non-preferred chamber because our hypothesis was that activation of iC++ would reduce spontaneous pain and drive increased dwell time in the LED-paired chamber. The following day, to assess optogenetic real-time place preference, the mice were placed in the centre of the apparatus for a 30-min session. During this session, EthoVision body contour tracking of the mouse centre point activated the blue LED when the centre point was detected in the originally non-preferred chamber, which in turn delivered 10-mW continuous light through the bifurcating fibre-optic implants for the entire duration that the mouse centre point was detected in the chamber; the LED would turn off when the mouse centre point was detected in the other chamber (closed-loop protocol). This procedure was repeated daily for seven consecutive sessions to optogenetic real-time place preference-induced learning rates over time. After the pretest and seven closed-loop optogenetic sessions, we performed one post-test session to assess if a conditioned place preference had developed. Here, the mice remained connected to the patch cables, but no light was delivered, and the time spent in each chamber was calculated. Increased time in the formally LED-paired chamber indicates a learned preference for iC++-mediated inhibition of ACC nociceptive MOR+ cell types.

Statistics and reproducibility

The MORp viruses used in Fig. 4 are available from the Gene Vector and Virus Core at Stanford University (https://neuroscience.stanford.edu/shared-resources/gvvc). In our laboratory, MORp–eYFP, MORp–hM4Di and MORp–FlpO have each been used successfully at least three times in independent experiments.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.