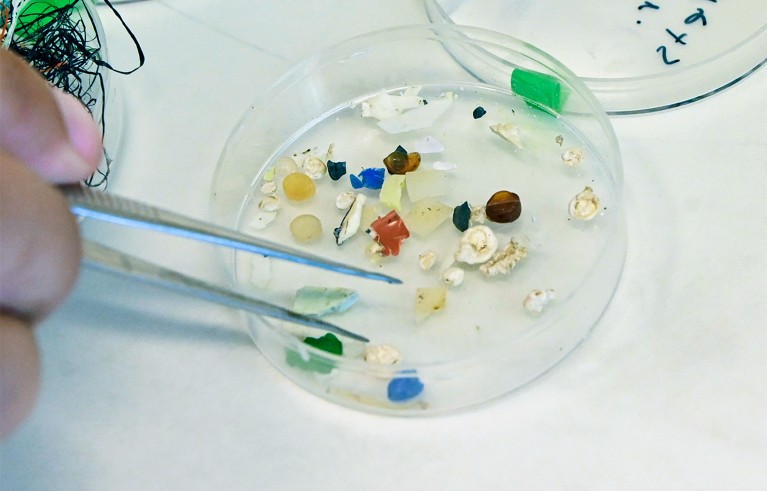

Microplastics are ubiquitous, but studies disagree on how much of the pollutants are in the atmosphere.Credit: Milos Bicanski/Getty

The amount of microplastic particles in the atmosphere might be lower than some studies have suggested, possibly even by several orders of magnitude. The finding, published on 21 January in Nature1, comes after a high-profile study, which was published in February, that suggested that the concentration of microplastics in the human brain might have been overestimated2.

“This doesn’t mean we don’t have a lot of microplastics in the atmosphere,” says Ioanna Evangelou, an environmental scientist at the University of Vienna. But it does point to a need to broaden and standardize the measurements of microplastics globally, she adds.

Many human activities — from improper disposal of waste to the degradation of car tyres — release small plastic particles, which have infiltrated the atmosphere, oceans and other ecosystems. These include nanoplastics — particles measuring less than 1 micrometre across — and microplastics, which range from 1 micrometre to around 5 millimetres. They’ve entered our bodies and brains, and scientists are still working to understand their effects on people’s health.

“We should not believe that this is not an issue,” says Evangelou. She hopes that the main message of the results will not be used to dismiss the problem of atmospheric microplastics. Research on the biological effects of microplastics is still in its infancy, which means that it is not clear whether the levels humans are exposed to — whatever those levels are — are safe.

Microplastic emissions

Studies that have estimated the concentration of microplastics in the atmosphere show high levels of variability, with results ranging across several orders of magnitude. And studies that have taken measurements from a region in the western United States have been used to infer global emissions.

Evangelou and her team aimed to get a better handle on microplastic concentrations by compiling two sets of existing studies — those that estimated global microplastic emissions, and those that measured the particles found in environmental samples. They then used the second set to assess the validity of the first.

The researchers fed the estimated emissions data into a computer simulation of how the atmosphere transports pollutants. The simulation gave predictions of the concentrations of microparticles that would be found across the globe. But the predicted amounts did not match those found in samples at 283 different locations worldwide.

The difference was stark — in some cases, the microplastic measurements from environmental samples were orders of magnitude smaller than the models predicted. The team also estimated that 27 times more microplastic particles are emitted from activities on land than from the ocean.

Are microplastics bad for your health? More rigorous science is needed

In particular, the study estimates that the amount of microplastics released from the ocean into the atmosphere is less than estimated in some previous studies, including one co-authored by Natalie Mahowald4, an atmospheric scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Mahowald says her team’s estimates had “huge uncertainty bars”, and they are still compatible with the new findings1.

“As stated in the paper, there are many continuing uncertainties in microplastics, and more data are needed, especially in new locations, and more information about the size distributions,” adds Mahowald.

Stephanie Wright, an environmental toxicologist at Imperial College London, says that one limitation of the study is that it included models of emissions from the degradation of tyres among the inputs — and that the microplastic particles released from tyres would not normally show up in environmental samples. Evangelou agrees, but she adds that her team included tyre particles as a proxy for general human activities that can release microplastics.