The Great Math War: How Three Brilliant Minds Fought for the Foundations of Mathematics Jason Socrates Bardi Basic (2025)

In the weeks leading up to September 1891, mathematician Georg Cantor prepared an ambush. For years he had sparred — philosophically, mathematically and emotionally — with his formidable rival Leopold Kronecker, one of Germany’s most influential mathematicians. Kronecker thought that mathematics should deal only with whole numbers and proofs built from them and therefore rejected Cantor’s study of infinity. “God made the integers,” Kronecker once said. “All else is the work of man.”

Stirring biopic of the first woman to win top maths prize

But Cantor had a proof that he hoped would confound his competitor. Armed with an innovative method, now known as Cantor’s diagonal argument, he could demonstrate that some infinities are larger than others and he planned to confront Kronecker with it in public at the inaugural meeting of the German Mathematical Society in Halle. But the showdown never came. Weeks before the meeting, Kronecker’s wife was fatally injured in a climbing accident, preventing him from going to Halle, and Kronecker himself died that December.

This tragedy — at once poignant, anticlimactic and painfully human — is one of many vivid digressions in journalist Jason Socrates Bardi’s The Great Math War. Bardi provides a lively narrative of the intellectual struggle that transformed the field in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. He uses drama to demonstrate how the long arc of modern maths — from the invention of rigorous analysis to the birth of set theory, logic and topology — was neither neat nor inevitable. The intellectual revolution reshaped ideas about the scope of maths, what counts as a valid proof and whether mathematical truth is discovered or invented. And it was driven as much by temperaments, loyalties, neuroses and sheer chance as by fresh theories.

The Fields Medal should return to its roots

The stakes of this ‘maths war’ were immense. Was maths grounded in intuition — the mental constructions that people can build step by step — or in formal symbols and rules that are independent of human insight? Were numbers objective features of reality or useful inventions of the human mind? And could the infinite be incorporated safely into maths, or would it lead to contradiction and collapse? Bardi deftly follows these questions as they ripple across Europe, shaping rival schools, polarizing university departments and fuelling philosophical, professional and, often, personal battles.

Human side of maths history

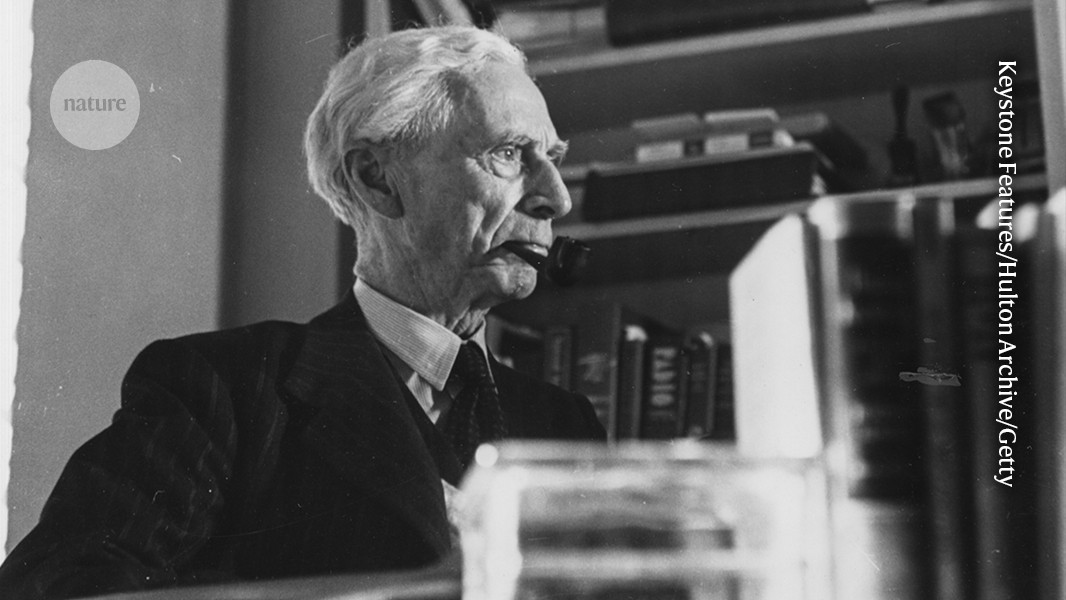

The book’s central argument — that maths is a human endeavour, shaped by human frailty as much as by formal proof — is made convincingly throughout. Bardi captures the period’s ferment with energy and empathy, paying close attention to the psychological states of its protagonists: Cantor’s oscillations between visionary triumph and crippling despair; L. E. J. Brouwer’s fervent mission to tear down maths and make it all anew; and Bertrand Russell’s tortured attempts to reconcile logic, certainty and his own emotional life, confided in anguished letters to his aristocrat lover, Lady Ottoline Morrell.

Aristocrat Ottoline Morrell corresponded extensively with philosopher Bertrand Russell.Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

The feud between Brouwer and David Hilbert in the 1920s was notorious. Hilbert championed formalism: the idea that maths should be reduced to axioms and rules, with meaning set aside in favour of consistency. Brouwer, by contrast, insisted that only proofs that the mind could follow were legitimate. In 1928, Hilbert, who was a chief editor of the leading journal Mathematische Annalen, tried to remove Brouwer from its editorial board. Brouwer refused to resign and was ousted — through dissolution of the entire board. Hilbert then rebuilt it with appointees of his choosing. Albert Einstein, a fellow Annalen chief editor, dismissed the whole affair as an overblown ‘frog and mouse war’.

For many readers who have encountered maths only as a technical tool, the heightened passions behind such debates might be hard to fathom. Yet, when Cantor was being denounced by his contemporaries, including Kronecker, as a charlatan and accused of corrupting the youth with his controversial ideas about infinity, the future of maths truly seemed at stake.

A Black mathematical history

Bardi is at his best when excavating the overlooked corners of history: the petty jealousies of editorial boards, the philosophical fights waged through open letters, the strain on marriages and the toll on mental health. He writes with breathless enthusiasm, occasionally slipping into staccato bursts — “Bereft. Pent-up” — that evoke his characters’ emotional turmoil. He brings comic energy to his narrative, for instance, by introducing ancient Greek mathematician Euclid as the “reigning heavyweight champion of math authors” until 1900.

Bardi excels in recounting Russell’s life and ideas. An imperialist turned peace activist and advocate of free love, Russell discovered a troubling paradox in maths, similar in its logical form to several others, including the ‘liar paradox’: if the sentence ‘this statement is a lie’, for instance, is true, then it means the statement is a lie — and therefore not true — leading to a logical inconsistency.