Think about your breakfast this morning. Can you imagine the pattern on your coffee mug? The sheen of the jam on your half-eaten toast?

Most of us can call up such pictures in our minds. We can visualize the past and summon images of the future. But for an estimated 4% of people, this mental imagery is weak or absent. When researchers ask them to imagine something familiar, they might have a concept of what it is, and words and associations might come to mind, but they describe their mind’s eye as dark or even blank.

The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery

Systems neuroscientist Mac Shine at the University of Sydney, Australia, first realized that his mental experience differed in this way in 2013. He and his colleagues were trying to understand how certain types of hallucination come about1, and were discussing the vividness of mental imagery.

“When I close my eyes, there’s absolutely nothing there,” Shine recalls telling his colleagues. They immediately asked him what he was talking about. “Whoa. What’s going on?” Shine thought. Neither he nor his colleagues had realized how much variation there is in the experiences people have when they close their eyes.

This moment of revelation is common to many people who don’t form mental images. They report that they might never have thought about this aspect of their inner life if not for a chance conversation, a high-school psychology class or an article they stumbled across (see ‘How do you imagine?’).

Although scientists have known for more than a century that mental imagery varies between people, the topic received a surge of attention when, a decade ago, an influential paper coined the term aphantasia to describe the experience of people with no mental imagery2.

Since then, aphantasia has shot into the canon of unusual phenomena that are invaluable for studying how the mind works. Like synaesthesia (in which people’s senses are connected in exceptional ways, so they hear colours, for example) and prosopagnosia (also known as face blindness), aphantasia has opened many new research avenues.

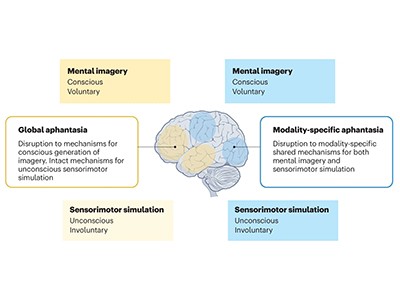

Much of the early work sought to describe the trait and assess how it affected behaviour. But over the past five years, studies have begun to explore what’s different about the brains of people with this form of inner life3. The findings have led to a flurry of discussions about how mental imagery forms, what it is good for and what it might reveal about the puzzle of consciousness: researchers tend to define mental imagery as a conscious experience, and some are now excited to study aphantasia as a way to probe imagery’s potentially unconscious forms.

Cognitive neuroscientist Giulia Cabbai at University College London is among the researchers interested in these questions. She was shocked to learn about aphantasia in 2015. Her own intensely vivid mental imagery is at the other extreme of the distribution — she has hyperphantasia. The fact that there are people with a complete lack of mental imagery brings fresh ways to study this internal experience, she says. “How does it affect our emotion, our perception, our attention, our memory? We can understand this with aphantasia.”

Genuine variation

Neurologist Adam Zeman at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Exeter, UK, began studying aphantasia in 2003. He met a man who, after a minimally invasive heart procedure, complained that although his visual perception remained normal, his mind’s eye had vanished. Scans of his brain showed the expected activity when he looked at images of famous faces, but notable differences from control individuals when he tried to imagine the faces. After Zeman’s team published a case study4 in 2010, Zeman heard from more than 20 people who said that they, too, lacked mental imagery, but they had lacked it their entire lives. Zeman’s team surveyed those people, reporting the findings and introducing the term aphantasia (tacking an ‘a’ to the front of ‘phantasia’, Aristotle’s term for the mind’s eye) in 2015 in Cortex2.

Zeman says that he was inundated with messages after an article about the paper appeared in The New York Times. Since that article, some 20,000 people have contacted him with their own stories of mental imagery.

“I didn’t expect it to explode quite as it has,” says Zeman. “If you are studying what you regard as a rare neuropsychological phenomenon and you get half a dozen people in touch, that’s big time.”

The 2015 paper and subsequent research has revealed how much aphantasia can vary. For instance, people with aphantasia often, but not always, lack the ability to imagine in sensory modalities besides vision — having no ‘mind’s ear’, for example. Some people with aphantasia report dreaming in pictures, but others don’t.

Researchers have also found that aphantasia seems to have a genetic component, with the likelihood of having aphantasia increasing tenfold if you have a sibling who has a weak or absent mind’s eye. And aphantasia might be more common in people in scientific and technical professions than in people with careers in the arts5.

Zeman and others say that aphantasia doesn’t seem to make much difference to behaviour, and although it might influence creativity, it by no means precludes it. Instead of calling it a disorder or condition, Zeman describes it as an “intriguing variation” — one extreme on a distribution of mental-imagery capabilities.

Getting a measure

Much of the work characterizing mental imagery relies on asking participants to describe their experience. But such methods are subjective, and they can’t separate true variations in experience from variations in how people describe or interpret that experience. So some researchers have been attempting to come up with other techniques.

Neuroscientist Joel Pearson at the University of New South Wales in Sydney and his colleagues developed an approach that takes advantage of a perceptual phenomenon called binocular rivalry. When a different visual is presented to each eye simultaneously, for example, a pattern of green lines to the left eye and red lines to the right, a person’s perception toggles between the two instead of blending them. Nearly two decades ago, Pearson decided to see what happened if he imagined one of the visuals in his mind’s eye — in this case, only the green lines or only the red — before the test began. It turned out that whichever pattern he imagined was what he saw during the test.

The researchers developed this finding into a technique to measure the strength of mental imagery6. In a person with typical mental imagery, imagining the red pattern results in the person being more likely to see that red pattern during binocular rivalry. But a person with no visual imagery will not show this same bias. Pearson has been studying mental imagery ever since developing this method7.

There are other techniques, too. A person’s emotional reaction to scary stories, measured by how much they sweat, can be a good proxy for how vividly they imagine what’s happening in the story. And when researchers ask someone to imagine a bright light, the extent to which their pupils constrict correlates with the vividness of their mental imagery.

The consciousness wars: can scientists ever agree on how the mind works?

A decade of work has left researchers convinced that aphantasia is a real phenomenon, but many are puzzled by how little it seems to affect behaviour. Behavioural tasks that are thought to depend on mental imagery don’t seem to be a problem for people with aphantasia. They perform relatively well on standard memory assessments and they seem to be able to rotate objects in their mind, to determine whether an object in one picture matches another presented from a different angle.

“I play sports. I can draw diagrams of the brain — whatever you want. But for me, when I try to imagine a purple dinosaur juggling on top of a bouncy ball, nothing shows up,” says Shine. He says the big mystery is how the brain can function typically in all these ways but at the same time lack this one specific ability.

Into the brain

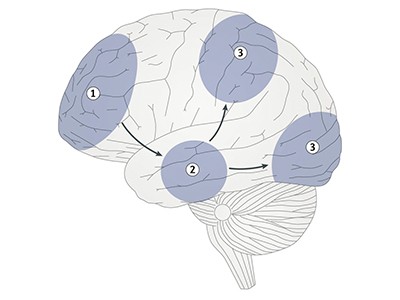

When scientists started looking for the brain signatures of aphantasia, they expected to see differences in the visual cortex. This is the area that receives and processes visual information during perception, and it’s known to be active when a person pictures something in their mind. Most researchers have thought of mental imagery as vision in reverse, with higher-level brain areas sending signals to lower visual areas to generate a conscious image.

But studies have suggested that when people with aphantasia attempt to imagine something, they activate the visual cortex in ways similar to that seen in control individuals. Perhaps, some researchers say, that brain area is forming visual representations in people with aphantasia, but the conscious mind can’t access what is there.

During her PhD, Cabbai decided to study the relationship between activity in the visual cortex and a person’s experience of imagery. She wanted to find out whether what she and others call ‘sensory representations’ in the visual cortex must always come with the experience of imagery. But she also wondered whether aphantasia was a problem with voluntarily conjuring up images on demand, so she and her colleagues took an approach that didn’t require participants to do that.

The team scanned the brains of people with and without aphantasia while they listened to sounds that should spontaneously trigger a sensory representation of whatever made the sound. Barking, for example, should trigger representations of a dog in the primary visual cortex. Then, the researchers fed the brain activity into a machine-learning algorithm to see whether it could predict the sound content.

Hearing a dog bark did generate activity that represented a dog in both typical imagers and people with aphantasia. But, despite the existence of that activity, people with aphantasia reported seeing nothing in their mind’s eye8. The finding suggests that these sensory representations — thought to underlie mental imagery — can remain unconscious and so are not sufficient to trigger imagery on their own.

Insights into embodied cognition and mental imagery from aphantasia

The team also probed voluntary imagery, asking participants to visualize what was making the sound. In this case, the algorithm couldn’t decode what was being represented in the visual cortex in people with aphantasia. Cabbai calls the findings “puzzling”, and says that aphantasia might be a twofold problem involving not experiencing imagery consciously and not being able to voluntarily generate it.