You have full access to this article via your institution.

Malaria cases are on the rise.Credit: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty

In 2015, the international community made a historic pledge to end epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other communicable diseases by 2030. Nations committed to achieving universal health coverage, and promised to ensure that everyone, everywhere had access to safe and affordable medicines and vaccines. These pledges formed the third goal in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which focuses on healthy lives and well-being for all. Achieving the goals by the UN’s deadline of 2030 was always going to be a stretch. But to have world leaders commit to these and other targets was no small achievement.

Some progress was recorded in the first five years after that landmark moment. There were fewer deaths among newborns and children under five. New HIV infections declined, and the proportion of the world’s population with access to universal health care continued to rise, albeit more slowly than before 2015. But, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, wars and other factors, average global life expectancy is now declining for the first time in decades. Polio, once on the brink of eradication, has re-emerged. Malaria cases have been rising since 2016.

It is unacceptable that more isn’t being done — and more can be done. We at Nature — and journals across the Nature Portfolio — remain determined to play what small part we can in progressing all of the SDGs. The goals are an important focus for our publisher, Springer Nature, too.

Synthetic data can benefit medical research — but risks must be recognized

Today sees the launch of a new journal, Nature Health, with the mission of “bridging the implementation gap from health research to policy and practice”. The journal’s first Editorial1 states: “We will prioritize research with real-world impact, especially when conducted in resource-limited settings, whether in low- and middle-income countries or in deprived communities elsewhere.”

The journal’s launch — and the challenges the publication seeks to help resolve — come at a time when scientific knowledge in medicine and health care is progressing at perhaps the most rapid pace in human history. From gene editing to 3D bioprinting, high-resolution imaging to robotic surgery, clinicians have tools that could revolutionize the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of disease. But there are stark disparities in health outcomes and life expectancies between people on high and low incomes. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) especially, routine public-health services such as clean water and sanitation are out of reach for billions2. There is an “unprecedented crisis” in financing for global health, writes Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the World Health Organization, in Nature Health’s first issue3. In 2025, international funding for health in Africa alone is projected to have fallen to below US$40 billion, from $80 billion in 2021, as wealthier countries slashed their health aid budgets, according to a News feature4.

The current crisis is a chance for countries to reduce, if not eliminate, their dependence on foreign aid, Tedros adds. In the process of building health systems, all countries must harness the talents of their researchers. The inaugural cohort of Calestous Juma Science Leadership Fellows, a group of scientists based in Africa and supported by the Gates Foundation in Seattle, Washington, has proposed focused actions in six thematic areas. Top of their recommendations, detailed in a Comment article, is for the private sector to lead research and development5.

This is a welcome call to action for the business community, not only to fill in the funding gaps left by departing international aid donors, but also to provide more, longer-term support for their countries’ public sectors. It offers an opportunity for business leaders to recognize the necessity of a strong and effective public sector — to support research, innovation and regulation — and that they bear some responsibility for helping to make this happen.

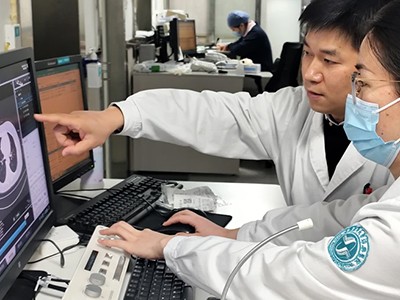

Businesses are also rapidly advancing artificial intelligence for the health-care sector. In a Perspective article also published in Nature Health’s launch issue, the authors highlight some case studies in which the application of large language models (LLMs) is improving diagnostics and supporting decision-making in LMICs6.

As we reported in a Nature Editorial last year, AI models are increasingly being trained on ‘synthetic’ data that is generated by algorithms7. The promise of these data for LMICs is that they are presumed to be able to mimic the statistical properties of real-world data, which are scarce, or difficult or costly to collect — and they do not need the same extent of ethical review.

However, as the authors of the Perspective article point out, LMICs face huge barriers to more widespread adoption of LLMs in this area, including limited digital infrastructure and an absence of relevant laws and regulations. There is an “urgent need” for evaluation studies, the researchers write, such as those using randomized controlled trials to independently verify claims being made for LLMs, as well as economic analyses that can evaluate any claims relating to their cost-effectiveness.

At Nature, at Nature Health and across the Nature Portfolio journals, we remain committed to playing our part in creating a world in which health and well-being can be experienced by all.