The US National Institutes of Health, located in Bethesda, Maryland, is composed of 27 institutes and centres.Credit: Duane Lempke (CC0)

The world’s largest public funder of biomedical research seems poised for a major overhaul in the next few years.

US funders to tighten oversight of controversial ‘gain-of-function’ research

Proposals from both chambers of the US Congress, as well as comments made by the incoming administration of US president-elect Donald Trump show that there is significant appetite to reform the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and its US$47-billion research portfolio. What’s less clear is how this transformation will unfold; proposals have included everything from shrinking the number of institutes by half to replacing a subset of the agency’s staff members.

Reflecting this increased scrutiny by the government, on 12 November, the NIH launched a series of meetings at which an advisory group of agency insiders and external scientists will consider the various proposals and offer its own recommendations for reforms.

It will be a mad dash to the finish line among these parties in terms of whose vision will win out, says Jennifer Zeitzer, who leads the public-affairs office at the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology in Rockville, Maryland. “There’s absolutely movement on Capitol Hill to discuss how to optimize and reform the NIH,” she says. “We now also have the agency participating in that conversation.”

Shrinking and cutting

The NIH advisory meeting comes in the wake of Republicans winning control of both chambers of Congress and the White House for 2025. This year, two separate legislative proposals to reform the agency were put forward by Republican congressional members — one led by representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers of Washington State and one by senator Bill Cassidy of Louisiana. These proposals have in part been fuelled by discontent over the agency’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the perception that its oversight of research on potentially risky pathogens has been lax.

McMorris Rodgers’s plan would collapse the number of institutes and centres at the NIH from 27 to 15, allow its parent agency to cancel any grant determined to be a threat to national security, impose a 5-year term limit on institute directors that can be renewed only once and enact stricter oversight of research involving risky pathogens. For his part, Cassidy, who is set to become the chair of the US Senate’s committee charged with overseeing health issues in 2025, said that he would introduce more transparency into processes that the agency uses to review research grant proposals.

If these plans — which are laid out in white papers — come to pass, they would represent the first major reform of the NIH in nearly 20 years. The last time an overhaul happened, in 2006, the US Congress passed the legislation with bipartisan support, establishing a review board and requiring the agency to send updates to lawmakers every two years. The same support from both sides of the political aisle is unlikely to happen with the proposals currently under consideration, however.

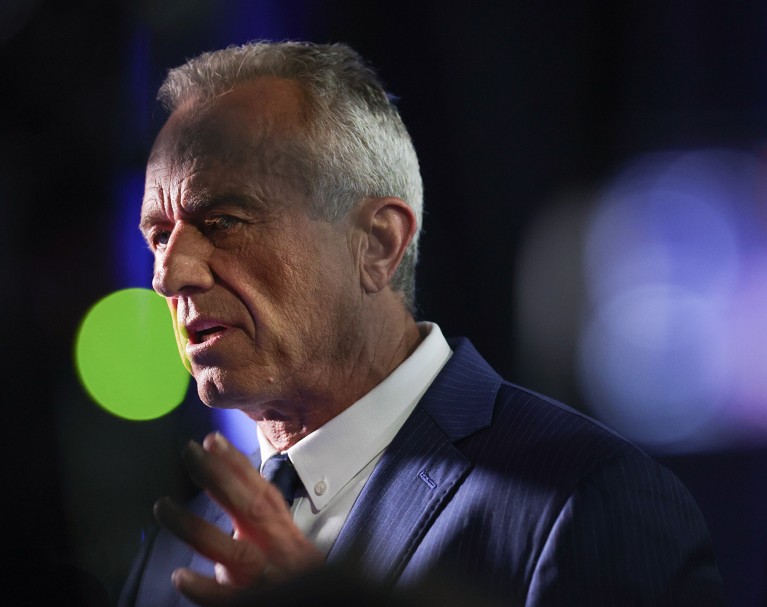

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., an environmental lawyer, was picked by US president-elect Donald Trump to lead the US Department of Health and Humans Services. He will need to be confirmed by the US Senate to assume that office.Credit: Bryan Dozier/Variety via Getty

The NIH has been a frequent target of Trump and his Republican and other allies. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who Trump has chosen to run the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) — the NIH’s parent agency — said in 2023 that he would seek an eight-year pause for infectious-diseases research at the NIH so that the biomedical funder can instead focus on chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity. He also said on 9 November that he would seek to replace 600 employees at the NIH. (Neither Trump nor his appointees can currently fire career staff members at the agency, whose jobs are protected by law, but that might change if Trump makes good on a promise to reclassify the federal workforce.)

Harold Varmus, a cancer researcher at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City and a former head of the NIH, tells Nature that he is “alarmed” by Kennedy’s comments. “We may need congressional Republicans and even Democrats who are traditional supporters of NIH to speak up for the agency and its importance for public health.”

Dash to the finish line

At this week’s meeting of the NIH’s advisory committee, called the Scientific Management Review Board (SMRB), panel members met for the first time since 2015 to review the agency’s structure and research portfolio and to provide recommendations to the NIH director and the HHS. Congress requested that the agency kick-start this process.

New NIH chief opens up about risky pathogens, postdoc salaries and the year ahead

NIH officials hope that the group will meet five more times during the next calendar year so that they could draft a report of their findings and recommendations by November 2025. This ambitious timeline suggests that “there’s a recognition that the SMRB is going to have to move quickly to catch up with Congress, or risk Congress making decisions that they don’t like”, Zeitzer says.

In fact, several committee members noted their trepidation during the 12 November meeting that Congress would act before the group delivers its report. Kate Klimczak, the NIH’s director of the office of legislative policy and analysis, tried to reassure the committee: “the authors of the different [congressional] proposals clearly wanted this board to be re-established and wanted this board to do their work,” she said. “We have to take them at their word that they’re looking forward to getting [a report] from you.”

NIH director Monica Bertagnolli, who will probably resign before Trump takes office, noted her disapproval with the proposals to collapse the number of institutes. She said that the current system offers people with diseases and patient-advocacy groups the ability to coordinate with a dedicated institute for their cause, for instance the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institute on Aging. “If we were to collapse, we would definitely lose something in terms of our engagement with the public,” she said.

It’s unclear what direction the SMRB will go with its recommendations, but there were hints at the meeting. Several panellists were taken aback by the legislative proposals. For example, the McMorris Rodgers white paper says that “decades of nonstrategic and uncoordinated growth created a system ripe for stagnant leadership, research duplication, gaps, misconduct and undue influence” at the NIH. James Hildreth, president of Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, called this language “almost offensive”. He added: “I know we’re not supposed to allow politics to creep into what we do, but how could it not?”