You have full access to this article via your institution.

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Children inherit two copies of most genes from their parents, but one copy of certain genes can be silenced. Credit: Oscar Wong/Getty

The effect of a gene can vary greatly — and sometimes be the complete opposite — depending on which parent it’s inherited from. A team of researchers have devised a statistical model that has revealed at least 30 of these parent-of-origin effects in 14 genes, all without needing genomic data from a person’s parents. Nineteen gene variants had a ‘bipolar effect’, meaning it had opposite effects depending on which parent it came from. One such variant increased the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 14% when inherited from the father but decreased it by 9% when inherited from the mother.

The UK Royal Society is converting eight of its ten journals to a ‘subscribe to open’ publishing model from next year. Under the model, article processing charges (APCs) — fees that authors pay to make their papers published open access — will be waived for these journals, and all content published that year will be free to access — as long as enough libraries commit to paying an annual subscription fee. Without sufficient subscriptions for 2026, the Royal Society will continue to offer APCs-based open-access options, and try again in 2027.

A powerful new large language model (LLM) released by OpenAI is the first to live up to the company’s name — it’s the firm’s first ‘reasoning’ artificial intelligence that researchers can download and customize. Known as gpt-oss, the LLM is available in two sizes, both of which can be run locally and offline — the smaller of them on a single laptop — rather than requiring cloud computing or an online interface. This means they can be used to analyse, or be trained further on, sensitive data that can’t be transferred outside a given network.

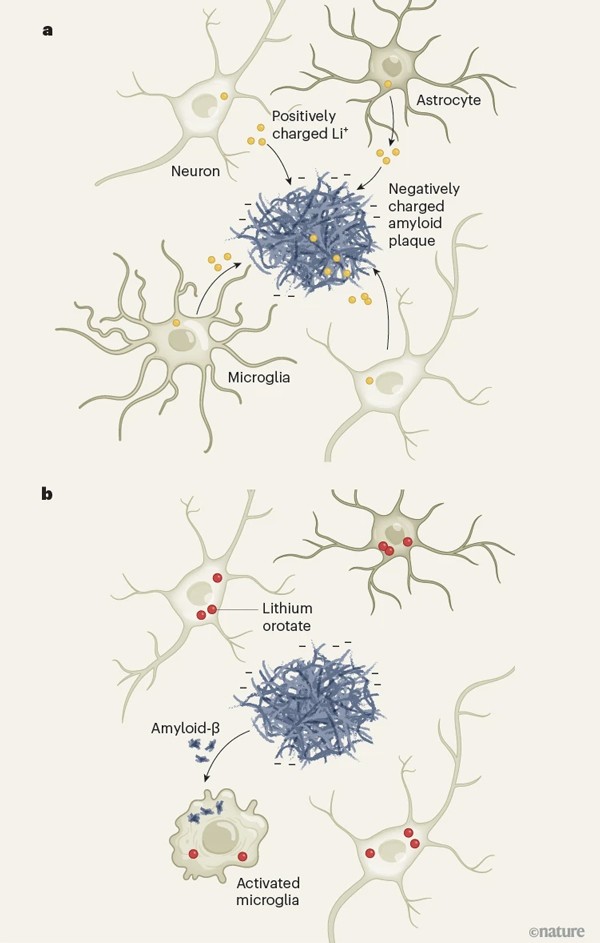

Replenishing the brain’s natural stores of lithium can protect against, and even reverse, Alzheimer’s disease in mice. Researchers found that in human brain tissue and mice, a decline in lithium concentration in the brain is linked to memory loss and the neurological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s — protein build-ups called amyloid plaques and tau tangles. The team found that these neurological changes were reversed in mice given a supplement containing a compound called lithium orotate. The molecule also restored the brain to a younger, healthier state and rolled back memory loss.

Amyloid plaques carry a negative charge, which draws positively charged lithium ions out of brain cells (a). The lithium-depleted cells then can’t function properly, leading to cognitive decline. Lithium orotate doesn’t easily form ions. As such, it can escape the pull of amyloid plaques and replenish the lost lithium in brain cells (b). (Nature News & Views | 8 min read)

Features & opinion

To determine which artificial intelligence tool is best at a particular task, you can use a benchmark — a test that can be used to compare the performance of different models. For that system to work, benchmarks need to be robust. That, machine learning researchers say, is where things fall down. Increasingly, artificial intelligence models are being designed to compare favourably against benchmark tests. That process yields tools that pass the tests, but do little else, flooding researchers with tools that aren’t fit for purpose.

In February, a preprint made waves in the world of mathematics by disproving the four-decade-old Mizohata-Takeuchi conjecture. Its author? 17-year-old Hannah Cairo. Cairo began to attend summer programs and classes at the University of California, Berkeley at just 14. It was there, working with mathematician Ruixiang Zhang, that she cracked the conjecture. Having already made her mark on mathematics, Cairo is headed for graduate school — without attending college, or even finishing high school. But she hasn’t let her success go to her head. “It looks like mathematically I’m, like, whatever,” she says.

Today I’m practicing my signature dance move. Not because I need to impress anyone; just for fun. And I’m not the only one who likes to dance for my own enjoyment. Researchers have found that captive cockatoos are also partial to a boogie, showing off at least 30 distinct moves.

The birds don’t even need music to break it down — they’re perfectly happy to bop along in silence or even while listening to a finance podcast.

Let me know if you’ve got a signature move, or have any feedback on this newsletter, at [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma