Kei Sato was looking for his next big challenge five years ago when it smacked him — and the world — in the face. The virologist had recently started an independent group at the University of Tokyo and was trying to carve out a niche in the crowded field of HIV research. “I thought, ‘What can I do for the next 20 or 30 years?’”

He found an answer in SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, that was rapidly spreading around the world. In March 2020, as rumours swirled that Tokyo might face a lockdown that would stop research activities, Sato and five students decamped to a former adviser’s laboratory in Kyoto. There, they began studying a viral protein that SARS-CoV-2 uses to quell the body’s earliest immune responses. Sato soon established a consortium of researchers that would go on to publish at least 50 studies on the virus.

In just five years, SARS-CoV-2 became one of the most closely examined viruses on the planet. Researchers have published about 150,000 research articles about it, according to the citation database Scopus. That’s roughly three times the number of papers published on HIV in the same period. Scientists have also generated more than 17 million SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences so far, more than for any other organism. This has given an unparalleled view into the ways in which the virus changed as infections spread. “There was an opportunity to see a pandemic in real time in much higher resolution than has ever been achievable before,” says Tom Peacock, a virologist at the Pirbright Institute, near Woking, UK.

Now, with the emergency phase of the pandemic in the rear-view mirror, virologists are taking stock of what can be learnt about a virus in such a short amount of time, including its evolution and its interactions with human hosts. Here are four lessons from the pandemic that some say could empower the global response to future pandemics — but only if scientific and public-health institutions are in place to use them.

Viral sequences tell stories

On 11 January 2020, Edward Holmes, a virologist at the University of Sydney, Australia, shared what most scientists consider to be the first SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence to a virology discussion board; he had received the data from virologist Zhang Yongzhen in China.

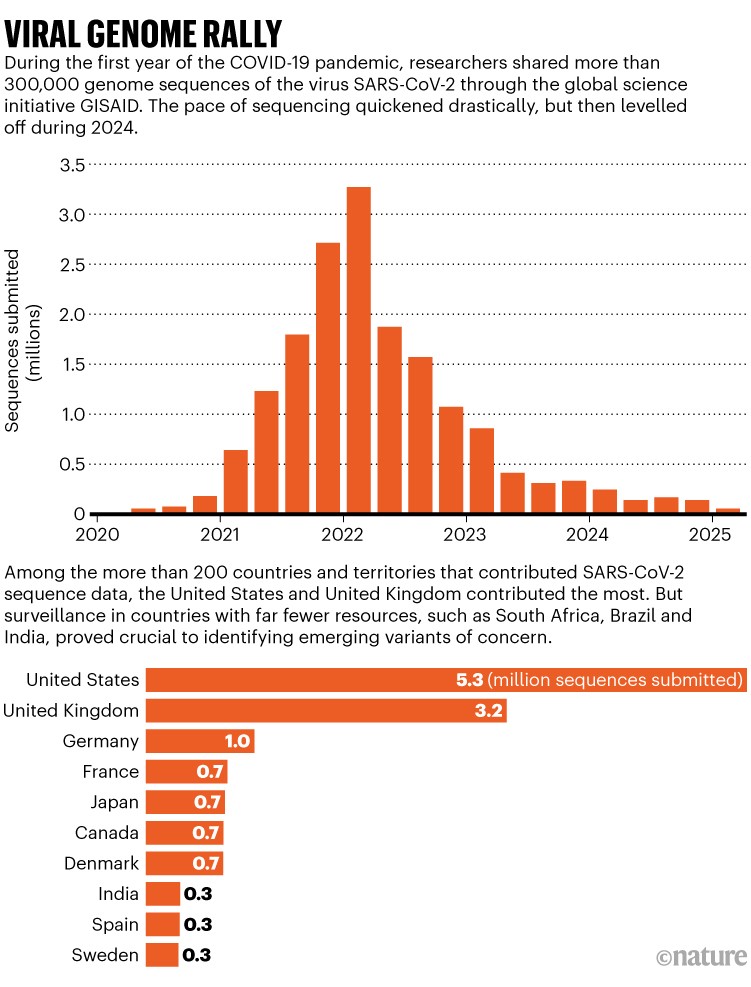

By the year’s end, scientists had submitted more than 300,000 sequences to a repository known as the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). The rate of data collection only got faster from there as troubling variants of the virus took hold. Some countries ploughed enormous resources into sequencing SARS-CoV-2: between them, the United Kingdom and the United States contributed more than 8.5 million (see ‘Viral genome rally’). Meanwhile, scientists in other countries, including South Africa, India and Brazil, showed that efficient surveillance can spot worrying variants in lower-resource settings.

Source: GISAID

In earlier epidemics, such as the 2013–16 West African Ebola outbreak, sequencing data came in too slowly to track how the virus was changing as infections spread. But it quickly became clear that SARS-CoV-2 sequences would arrive at an unprecedented volume and pace, says Emma Hodcroft, a genomic epidemiologist at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel. She works on an effort called Nextstrain, which uses genome data to track viruses, such as influenza, to better understand their spread. “We had developed so many of these methods that, in theory, could have been very useful,” Hodcroft says. “And all of a sudden, in 2020, we had an opportunity to put up and show up.”

Vaccine sceptic RFK Jr is now a powerful force in US science: what will he do?

Initially, SARS-CoV-2 sequencing data were used to trace the spread of the virus at its epicentre in Wuhan, China, and then globally. This answered key early questions — such as whether the virus spread largely between people or from the same animal sources to humans. The data revealed the geographical routes through which the virus travelled, and showed them much more quickly than could conventional epidemiological investigations. Later, faster-transmitting variants of the virus started appearing, and sent sequencing labs into hyperdrive. A global collective of scientists and amateur variant trackers trawled through the sequence data constantly in search of worrying viral changes.

“It became possible to track the evolution of this virus in tremendous detail to see exactly what was changing,” says Jesse Bloom, a viral evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington. With millions of SARS-CoV-2 genomes in hand, researchers can now go back and study them to understand the constraints on the virus’s evolution. “That’s something we’ve never been able to do before,” says Hodcroft.

Viruses change more than expected

Because no one had ever studied SARS-CoV-2 before, scientists came with their own assumptions about how it would adapt. Many were guided by experiences with another RNA virus that causes respiratory infections: influenza. “We just didn’t have much information about other respiratory viruses that could cause pandemics,” says Hodcroft.

Influenza spreads mainly through the acquisition of mutations that allow it to evade people’s immunity. Because no one had ever been infected with SARS-CoV-2 before 2019, many scientists didn’t expect to see much viral change until after there was substantial pressure placed on it by people’s immune systems, either through infections or better yet, vaccination.

The emergence of faster-transmitting, deadlier variants of SARS-CoV-2, such as Alpha and Delta, obliterated some early assumptions. Even by early 2020, SARS-CoV-2 had picked up a single amino-acid change that substantially boosted its spread. Many others would follow.

What sparked the COVID pandemic? Mounting evidence points to raccoon dogs

“What I got wrong and didn’t anticipate was quite how much it would change phenotypically,” says Holmes. “You saw this amazing acceleration in transmissibility and virulence.” This suggested that SARS-CoV-2 wasn’t especially well adapted to spreading between people when it emerged in Wuhan, a city of millions. It could very well have fizzled out in a less densely populated setting, he adds.

Holmes wonders, also, whether the breakneck pace of observed change was merely a product of how closely SARS-CoV-2 was tracked. Would researchers see the same rate if they watched the emergence of an influenza strain that was new to the population, at the same resolution? That remains to be determined.

The initial giant leaps that SARS-CoV-2 took came with one saving grace: they didn’t drastically affect the protective immunity delivered by vaccines and previous infections. But that changed with the emergence of the Omicron variant in late 2021, which was laden with changes to its ‘spike’ protein that helped it to dodge antibody responses (the spike protein allows the virus to enter host cells). Scientists such as Bloom have been taken aback at how rapidly these changes appeared in successive post-Omicron variants.

How months-long COVID infections could seed dangerous new variants

And that wasn’t even the most surprising aspect of Omicron, says Ravindra Gupta, a virologist at the University of Cambridge, UK. Shortly after the variant emerged, his team1 and others noticed that, unlike previous SARS-CoV-2 variants such as Delta that favoured the lower-airway cells of the lung, Omicron preferred to infect the upper airways. “To document that a virus shifted its biological behaviour during the course of a pandemic was unprecedented,” says Gupta.

Omicron’s preference for upper airways probably contributed to its clinical mildness — its relatively low virulence — compared with previous iterations. But that shift is hard to disentangle from the fact that Omicron struck after much of the world had begun to establish some immunity, says Bloom, and there is evidence2 that Omicron was just as nasty as the version of SARS-CoV-2 that emerged in Wuhan.

And although Omicron and its offshoots were milder than Alpha, Beta and Delta, those had all proved more virulent than the lineage they replaced, toppling the idea that the virus would evolve to be less deadly. “The idea that there’s some law of nature that says that a virus is going to rapidly lose its virulence when it jumps into a new host is incorrect,” Bloom says. It’s an idea that never had much buy-in with virologists anyway.

One of Sato’s big fears is that a drastically different SARS-CoV-2 variant will emerge and overcome the immunity that stops most people becoming severely ill. He worries that the result could be disastrous.

Chronic cases could reveal insights

Before Gupta turned his attention to SARS-CoV-2, his focus was HIV, which is ordinarily a lifelong infection. As a clinician, he had treated the second person ever cured of HIV through a blood stem-cell transplant. But his research group studied how antiretroviral drug resistance evolves over the course of months and years in people.

Most scientists presumed that, unlike HIV or other long-term infections, respiratory viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 were acute, and those who survived their infections cleared the virus in a matter of days. Longer-term infections occur in influenza, but they seem to be an evolutionary dead end. The virus adapts to survive in the host, not to spread to others.

Scientists in New Delhi prepare coronavirus samples for sequencing.Credit: T. Narayan/Bloomberg via Getty Images

But in late 2020, Gupta characterized a 102-day SARS-CoV-2 infection in a man in his 70s with a compromised immune system. The infection was ultimately fatal3. In the man’s body, the virus developed a high number of spike-protein changes. Many of these would also be observed in worrying variants, including the Alpha variant that sent case counts rocketing and prompted another wave of lockdowns in late 2020 and early 2021.

The man’s case didn’t give rise to any widespread variant, but it gave Gupta, with his HIV evolution background, the idea that chronic infections could be a source of the drastic evolutionary leaps that characterized SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. “We didn’t have the preconceptions the flu field had of what respiratory viruses do,” he says.

Alex Sigal, a virologist at the Africa Health Research Institute in Durban, South Africa, had a similar idea when another variant, called Beta, was identified in his country. South Africa has a high rate of HIV infections — many of which go untreated — and Sigal wondered whether it was more than a coincidence that Beta seemed to have emerged where there were high numbers of people who were immunocompromised.