Experiment

Production

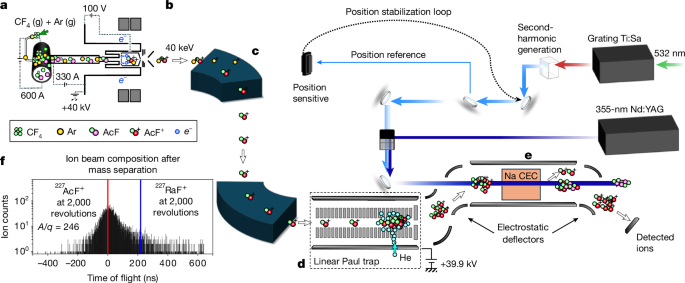

The ionization potential of AcF was predicted to lie above the threshold for efficient ionization by contact with a hot surface. In addition, without knowledge of its electronic structure, resonance laser ionization could not be used to produce ion beams of AcF+. The forced-electron-beam-induced arc-discharge (FEBIAD)-type ion source was chosen and operating parameters were identified for the production of AcF+. The UCx target in the FEBIAD-type ion-source unit was irradiated for 114.4 hours (4.77 days) before the start of the experiment, receiving 1.7 × 1018 protons, or a total of 73.774 μAh. During irradiation, the target unit was kept under vacuum (about 1 × 10−6 mbar) and the target container was resistively heated to slightly above room temperature to prevent condensation during irradiation. At the start of the experiment, the tantalum cathode of the ion source was resistively heated to 1,950 °C to facilitate electron emission. An anode voltage of 100 V was applied to the anode grid to accelerate the electrons and induce ionization within the anode volume, which was also maintained at 100 V with a magnetic-confinement field induced by applying a current of 2.8 A to the ion-source electromagnet. A bias voltage of 40 kV was applied to the target and ion-source unit, such that the ion beam was extracted to the ground potential of the beamline with an energy of 40.1 keV.

The target temperature was increased from about 1,300 °C at the start of the experiment up to 2,000 °C by heating in steps on the order of 10 A to maintain a continuous supply of AcF+. A mix of 10% CF4 and 90% Ar gas was added to the target via a leak of 1.5 × 10−4 mbar l s−1 calibrated for He, injecting 0.065 nmol s−1 of CF4 for the formation of fluoride molecules.

An extensive beam purity investigation was performed using α-decay spectroscopy of implanted ions and multi-reflection time-of-flight mass spectrometry using the ISOLTRAP apparatus23,49. The main expected isobaric contaminant, 227Ra19F+, was eliminated owing to the asynchronous proton irradiation and nuclide extraction, taking advantage of the drastically longer half-life of 227Ac (21.8 years) compared with 227Ra (42 minutes). The time-of-flight spectra in Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 3 show that the ion beam delivered for study was purely composed of 227Ac19F+, with no identifiable contaminants above background.

Collinear resonance ionization spectroscopy

At CRIS, the molecular beam was temporally and spatially overlapped in a collinear geometry with pulsed lasers that step-wise excited the molecular electron to ionization. At the end of the laser–molecule interaction region, the ionized molecules were deflected from the path of the residual neutral beam onto a single-ion detector. The excitation spectra were produced by monitoring the ion count rate on the detector as a function of the laser excitation wavenumbers.

Prior ab initio calculations of the excitation energies in AcF (ref. 27) predicted the (8)1Π state to lie at 26,166(450) cm−1 above X1Σ+. The 1σ error of ±450 cm−1 required a scanning range of 1,800 cm−1 to have 95% probability of discovering the predicted transition. Such a wide range is challenging for continuous scanning of light produced from a single-pass β-barium borate SHG crystal, as the SHG crystal angle requires active stabilization to ensure optimal frequency doubling for all fundamental wavenumbers, while small deviations from the optimal crystal angle also lead to the doubled light exiting the crystal at an angle. The latter issue is exacerbated by the distance between the laser table and the beamline, exceeding 15 m, which means that small exit angles from the SHG crystal lead to the laser light not entering the CRIS beamline.

To compensate for both issues, an active crystal-angle stabilization system was constructed using a ThorLabs PIAK10 piezoelectric inertia actuator, controlled with a proportional-integral-derivative loop reading a fraction of the SHG power output with the help of a beam sampler. To ensure that the second-harmonic light always followed the optimal trajectory for interaction with the molecules in the CRIS interaction region, a commercial active laser-beam stabilization system from MRC Systems was also installed, as shown in Fig. 1. This extended the continuous scanning range from 5 cm−1 without stabilization to about 1,450 cm−1.

The observed excitation wavenumber for (8)1Π ← X1Σ+ was determined by simultaneously monitoring the laser wavenumber and the ion acceleration voltage, defining the kinetic energy of the beam. The wavenumber of the fundamental Ti:Sa laser was monitored with a four-channel HighFinesse WSU-2 wavemeter and the acceleration voltage of the 227AcF+ ions delivered by CERN-ISOLDE was monitored with a 7.5-digit digital multimeter (Keithley DMM7510) with a precision of 100 mV. To trace long-term drifts of the wavemeter, a grating-stabilized diode laser (TOPTICA dlpro) locked to a hyperfine transition in a Rb vapour cell (TEM CoSy) was also continuously monitored by the wavemeter. The small difference in wavelength between the Rb line (about 780 nm) and the fundamental wavelength of the Ti:Sa in this work (about 774 nm) provided confidence that the drift correction is valid in the fundamental wavelength region where the (8)1Π ← X1Σ+ transition was discovered.

The arc-discharge ion source was chosen to ionize AcF because the molecule’s ionization potential (calculated at 6.06(2) eV (ref. 27)) exceeds the work function of rhenium, tantalum and tungsten that are used for high-temperature surface ionization. Ionization by electron bombardment was expected to lead to rotationally hot molecules that may lead to prohibitively low spectroscopic efficiency. To measure the rotational temperature of the beam, the fundamental harmonic of the Ti:Sa laser at 752 nm (in the molecular rest frame) was used in conjunction with the 355-nm non-resonant ionization step to perform spectroscopy of the A2Π1/2 ← X2Σ1/2 transition in 226RaF. Using the molecular constants extracted from the rotationally resolved spectroscopy of the molecule61, the rotational temperature was fitted to extract Trot = 1,200(80) K. In absence of any prior information of the AcF spectra, this temperature was used in the spectroscopic analysis.

Relativistic coupled cluster calculations

The relativistic coupled cluster calculations of the sensitivity \(W_\mathcalS\) of AcF to the nuclear Schiff moment of Ac were carried out using the development version of the DIRAC program62, which allows the use of relativistic methods within the four-component Dirac–Coulomb Hamiltonian. The single-reference coupled cluster approach with single, double and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) was used within the finite-field approach, following the implementation presented in ref. 63.

Throughout this study, we used the relativistic Dyall basis sets64,65 of different quality for the actinium and fluorine atoms; for the \(W_\mathcalS\) calculations, the basis sets for actinium were also manually optimized following the recommendation of ref. 63 and are described in Supplementary Information.

The calculations were carried out at the equilibrium bond distance (Re = 3.974 a0) obtained via structure optimization carried out at the DC-CCSD(T) level, correlating 50 electrons with active space from −20 Eh to 50 Eh (corresponding to 4f, 5s, 5p, 5d, 6s, 6p, 7s for Ac and 2s, 2p for F) in units of Hartree energy. The Re optimization was performed using the s-aug-dyall.cvnz (n = 2, 3, 4) basis sets and the results were extrapolated to the complete basis set limit (CBSL). For basis set extrapolation, we used the scheme of ref. 66 (H-CBSL).

An extensive computational study was carried out to evaluate the effect of different parameters on the obtained value of the \(W_\mathcalS\) factor and to evaluate the final uncertainty, following procedures used in the past for various atomic and molecular properties67,68,69,70,71. The four main sources of uncertainty in these calculations are the incompleteness of the employed basis set, the approximations in the treatment of electron correlation, the missing relativistic effects and the uncertainty in the equilibrium geometry. As we are considering high-order effects, these error sources are assumed to be largely independent, and hence they are treated separately. We consider contributions from the electron–electron Breit interaction and QED effects as the leading missing relativistic contributions. We estimated their order of magnitude by computing the uncorrelated Gaunt term, which can be used to gauge the size of these corrections. Supplementary Information provides details of the computational study and the uncertainty evaluation. Our conservative uncertainty estimate is 7.0%, dominated by the uncertainty in the calculated equilibrium geometry. The final recommended value of \(W_\mathcalS\) is \(-\mathrm7,748\pm 545\,e/4\rm\pi \epsilon _a_^4\).

2c-ZORA-cGHF calculations

On the level of two-component complex generalized Hartree–Fock (cGHF) and two-component complex generalized Kohn–Sham (cGKS) employing the hybrid LDA functional, which includes 50% Fock exchange, proposed by Becke (BHandH)72, quasirelativistic effects are incorporated within the zeroth-order-regular-approximation (ZORA) framework73,74. As suggested by ref. 75, a normalized spherical Gaussian nuclear charge density distribution is used for the isotopes 227Ac and 19F. The gauge dependence of the ZORA framework is alleviated by a model potential as suggested by ref. 76 with additional damping of the atomic Coulomb contribution to the model potential77.

The wavefunction was obtained self-consistently with convergence achieved when the change in energy between two self-consistent field cycles was less than 10−9 Eh and the relative change in the spin–orbit-coupling energy contribution was lower than 10−13%. Energy optimizations of the bond lengths were performed up to a change in the Cartesian gradient of 10−5 Eh/a0. Excited electronic states were obtained self-consistently, using the maximum overlap method (MOM)78, where the occupation numbers were chosen according to the determinant’s overlap with the previous self-consistent field cycle or the initial guess (IMOM79). At the Ac centre, Dyall’s core-valence triple-ζ basis set with mono-augmentation was used with added s and p functions in an even-tempered manner up to an exponent of 6 × 109 and a multiplicator of 3 (Supplementary Information). At the fluorine centre, Dyall’s core-valence triple-ζ basis set was used without additional modifications. All basis sets were employed without contrations.

A characterization of the ground state of AcF and three exemplary excited states, which have not been experimentally observed so far, are shown in Extended Data Table 1.

Utilizing the toolbox approach described in ref. 34, the parity- or time-odd (P,T-odd) properties of the electronic states were obtained as expectation values and from a linear-response ansatz80,81, respectively, the latter for Wd and Wsps (labelled \(W_\rmd^\rmm\) and \(W_\rmsps^\rmm\)). A complete list of the equations for each property is given in Table 6 of ref. 36.

In Extended Data Table 2, P,T-odd properties computed with this method are shown for the states presented in Extended Data Table 1 and compared with the 3Δ1 states in HfF+, ThO and ThF+, and the 1Σ+ states in RaOCH3+ and TlF.

Vibrational corrections were estimated by solving the vibrational Schrödinger equation within a discrete variable representation on a one-dimensional grid82 ranging from 3.18 a0 to 4.77 a0, divided into 1,000 equidistant points. The properties were interpolated as a sixth-order polynomial function of the bond length, and effects were estimated as described in the supplementary material of ref. 83. The change in the properties as a function of the bond length was computed and is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a.

The enhancement factor \(W_\mathcalS\) for the nuclear Schiff moment with 2c-ZORA-cGHF evaluates to \(W_\mathcalS=-\mathrm8,400\,e/4\rm\pi \epsilon _a_^4\), whereas further treatment of electron correlation at the level 2c-ZORA-cGKS with the BHandH functional leads to \(W_\mathcalS=-\,\mathrm8,700\,e/4\rm\pi \epsilon _a_^4\), which is close to the results from CCSD(T). The 2c-ZORA values were obtained after minimization of the energy with respect to the bond length (Re = 4.05a0 compared with CCSD(T) computations Re = 3.97 a0 from this work), suggesting that electron correlation is of importance for the bond length and hence the rotational constant, and, thus, indirectly, also for the sensitivity to CP-odd properties in the ground state of AcF.

When comparing the molecular sensitivity \(W_\mathcalS\) to the nuclear Schiff moment in AcF with that in other closed-shell systems, such as RaOCH3+ and TlF (Supplementary Fig. 4b), a Z2 scaling is expected84, but a reduced enhancement is computed for AcF. Contributions from the individual spinors to \(W_\mathcalS\) show that the bonding spinors—that is, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)—contribute with sign opposite to the other spinors but with a similar magnitude. In the case of the ground state computed on the level of 2c-cGHF, the HOMO contributes with \(\mathrm29,067\,e/4\rm\pi \epsilon _a_^4\) and the remaining orbitals sum up to \(-\mathrm37,481\,e/4\rm\pi \epsilon _a_^4\). For excited electronic states, the HOMO contributes to \(W_\mathcalS\) with the same sign but lower magnitude, resulting in a larger value of \(W_\mathcalS\) (see discussion in the main text and Fig. 2b of the supplementary material in ref. 85; also discussion in ref. 33). The suitability of these states for precision experiments depends on their radiative lifetime, among other factors, and thus a discussion is pending experimental observation.

NDFT calculations

The NDFT calculations were performed using the HFODD program86. The laboratory Schiff moment, Slab, can be calculated using second-order perturbation theory as

$$S_\rmlab\approx \sum _k\ne 0\frac \varPsi _\rangle E_-E_k+\,\rmc.c.,$$

(5)

where \(\widehatS_\) is the Schiff operator and \(\widehatV_\rmP,T\) stands for the P,T-violating potential. The index k refers to the excited states with the same angular momentum quantum numbers as the ground state \(| \varPsi _\rangle \) but opposite parity. To leading order, the Schiff operator \(\widehatS_\) is defined as

$$\widehatS_=\frace10\sqrt\frac4\rm\pi 3\sum _\rmp\left(r_\rmp^3-\frac53\overliner_\,\textch\,^2r_\rmp\right)Y_10(\varOmega _\rmp),$$

(6)

where the sum ranges over all protons (index p), Y10(Ω) is the spherical harmonics Yℓm(Ω) with ℓ 1, m = 0, and \(\overliner_\,\rmch^2\) is the mean-squared charge radius. In the coordinate representation, \(\widehatV_\rmP,T\) takes the form8,9,87

$$\beginarrayl\widehatV_\rmP,T(\bfr_1-\bfr_2)\\ =\; -\fracgm_\rm\pi ^28\rm\pi m_N\left\(\boldsymbol\sigma _1-\boldsymbol\sigma _2)\cdot (\bfr_1-\bfr_2)\left[\barg_\overrightarrow\tau _1\cdot \overrightarrow\tau _2-\frac\barg_12(\tau _1z+\tau _2z)+\barg_2(3\tau _1z\tau _2z-\overrightarrow\tau _1\cdot \overrightarrow\tau _2)\right]\right.\\ \,-\left.\frac\barg_12(\boldsymbol\sigma _1+\boldsymbol\sigma _2)\cdot (\bfr_1-\bfr_2)(\tau _1z-\tau _2z)\right\\frac \bfr_1-\bfr_2m_\rm\pi \left[1+\frac1m_\rm\pi \right]\\ \,+\frac12m_N^3[\barc_1+\barc_2\overrightarrow\tau _1\cdot \overrightarrow\tau _2](\boldsymbol\sigma _1-\boldsymbol\sigma _2)\cdot \boldsymbol\nabla \delta ^3(\bfr_1-\bfr_2),\endarray$$

(7)

where isovector operators are denoted by arrows, τz is +1 (−1) for neutrons (protons), the pion mass is mπ = 0.7045 fm−1, the nucleon mass is mN = 4.7565 fm−1, and \(\barg_\), \(\barg_1\) and \(\barg_2\) are the unknown isoscalar, isovector and isotensor CP-odd pion–nucleon coupling constants, respectively. The strong πNN coupling constant is denoted by g, and \(\barc_1\) and \(\barc_2\) are the coupling constants of a CP-odd short-range interaction.

The \(\rmI^\rm\pi =\frac3^-2\) ground state \(| \varPsi _\rangle \) of 227Ac has a \(\rmI^\rm\pi =\frac3^+2\) partner state \(| \bar\varPsi _\rangle \) at \(\Delta E\equiv E_\bar\varPsi _-E_\varPsi _=27.369\,\rmkeV\) (ref. 39). Owing to the small energy difference ΔE and in the absence of other reported low-lying \(\frac3^+2\) states, equation (5) reduces to

$$S_\rmlab\approx -\,2\rmRe\frac\langle \varPsi _\Delta E.$$

(8)

In octupole deformed nuclei, the NDFT calculation breaks parity and rotational symmetries, and the obtained nuclear wave function is the deformed quasiparticle vacuum, \(| \varPhi _\rangle \), defined in the body-fixed frame of the nucleus. The intrinsic state, \(| \varPhi _\rangle \), needs to be projected onto the laboratory states with well-defined angular momentum and parity. In the rigid deformation approximation, the matrix elements in the numerator of equation (8) read:

$$\langle \varPsi _| \widehatS_ \bar\varPsi _\rangle _\rmrigid=\fracJJ+1S_\rmint,$$

(9)

$$\langle \bar\varPsi _| \widehatV_\rmP,T \varPsi _\rangle _\rmrigid=\langle \widehatV_\rmP,T\rangle $$

(10)

where \(J=\frac32\) for 227Ac, Sint is the intrinsic Schiff moment and \(\langle \widehatV_\rmP,T\rangle \) is the intrinsic expectation value of the operator \(\widehatV_\rmP,T\). In terms of the coupling constants g, \(\barg_i\) and \(\barc_i\), the expectation value \(\langle \widehatV_\rmP,T\rangle \) can be rewritten as

$$\langle \widehatV_\rmP,T\rangle =v_\,g\barg_+v_1\,g\barg_1+v_2\,g\barg_2+w_1\barc_1+w_2\barc_2.$$

(11)

The insertion of equations (9)–(11) into equation (8) leads to the expression of Slab as

$$S_\rmlab=a_g\barg_+a_1g\barg_1+a_2g\barg_2+b_1\barc_1+b_2\barc_2,$$

(12)

where

$$a_i=-\frac2JJ+1\fracS_\rmintv_i\Delta E\ \ \ \,\rmand\,\ \ \ b_i=-\frac2JJ+1\fracS_\rmintw_i\Delta E$$

(13)

have units of e fm3.

As shown in ref. 10, there is a strong correlation between the intrinsic Schiff moment Sint in one odd nucleus and the intrinsic matrix element of the octupole charge operator88

$$\widehatQ_30=e\sum _pr_\rmp^3Y_30(\varOmega _\rmp)$$

(14)

in another even–even nucleus with close proton and neutron numbers. The correlation is visualized in Supplementary Fig. 5 using several Skyrme functionals within the Hartree–Fock–Bogoliubov method used in this work. For each functional, the neutron and proton pairing strengths were adjusted to reproduce the experimental pairing gaps of 229Th and 227Ac, respectively. The strong correlation between these two observables were used in a scheme to determine the intrinsic Schiff moment of a nucleus without relying on the results obtained with a specific functional. Using a variety of functionals, the intrinsic Schiff moment of 227Ac and the intrinsic electric octupole moment of 226Ra were calculated, and linear regression analysis was performed to determine the relationship between the two correlated observables. The resulting regression line was then used along with the measured value of the electric octupole moment of 226Ra, yielding the value of the intrinsic nuclear Schiff moment of 227Ac reported in this work. Details on the procedure and uncertainty estimation are given in Supplementary Information.

Global analysis

The measurement model of ref. 36 was expanded to explicitly contain two different pion–nucleon coupling constants \(\barg_\), \(\barg_1\) and the assumption \(d_\rmp^\rmsr=-\,d_\rmn^\rmsr\), where the suggestions of ref. 37 are followed.

In the Hamiltonian in equation (3), seven fundamental P,T-odd parameters contribute to the total atomic or molecular EDM. Considering experiments using 129Xe (refs. 50,51), 171Yb (ref. 52), 133Cs (ref. 53), 199Hg (ref. 11), 205Tl (ref. 54), 225Ra (refs. 13,55), 174YbF (refs. 48,56), 180HfF+ (ref. 57), 205TlF (ref. 58), 207PbO (ref. 59), 232ThO (ref. 60) and 227AcF, this results in a 12 × 7 matrix W, where the element in row i and column j corresponds to the Hamiltonian term in equation (3) for atom/molecule i and P,T-odd constant j. Electronic-structure coefficients for all atoms and molecules except AcF were taken from ref. 36 and nuclear-structure coefficients were taken from ref. 1, where available. Otherwise nuclear-structure estimates reported in ref. 36 were used. Combined with the vector of the P,T-odd constants \(\bfx_\rmPT^\rmT=[k_\rmT,k_\rmp,k_\rmsps,\barg_,\barg_1,d_\rme,d_\rmp^\rmsr]\) and the vector of the experimental frequency shifts \(\bff^\rmT=[\delta f_1,\ldots \delta f_7]\), the model is a system of linear equations of the form

$$h\bff=\bfW\bfx_\rmPT.$$

(15)

Following ref. 36, the restrictive power of a set of experiments can be determined by the volume enclosed by an ellipsoid in the seven-dimensional parameter hyperspace for a given confidence level. The global constraints on individual parameters are given by the extrema of the ellipsoid and are provided in Extended Data Table 3. It should be noted that a precision better than 1 mHz in the proposed 227AcF experiment would not further improve global constraints on individual parameters, as these are limited by the experiments with the largest uncertainties (see also ref. 37 for a discussion).