Membership at many of the high-level advisory coucils for the US National Institutes of Health is dwindling ― a decline that could trigger a freeze in issuance of some grants.Credit: Grandbrothers/Alamy

Crucial grant-review panels for more than half of the institutes that make up the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) are on track to lose all their voting members within the year. Federal law requires these panels to review applications for all but the smallest grants before funding can be awarded, meaning that the ability of those institutes to issue new grants could soon be frozen.

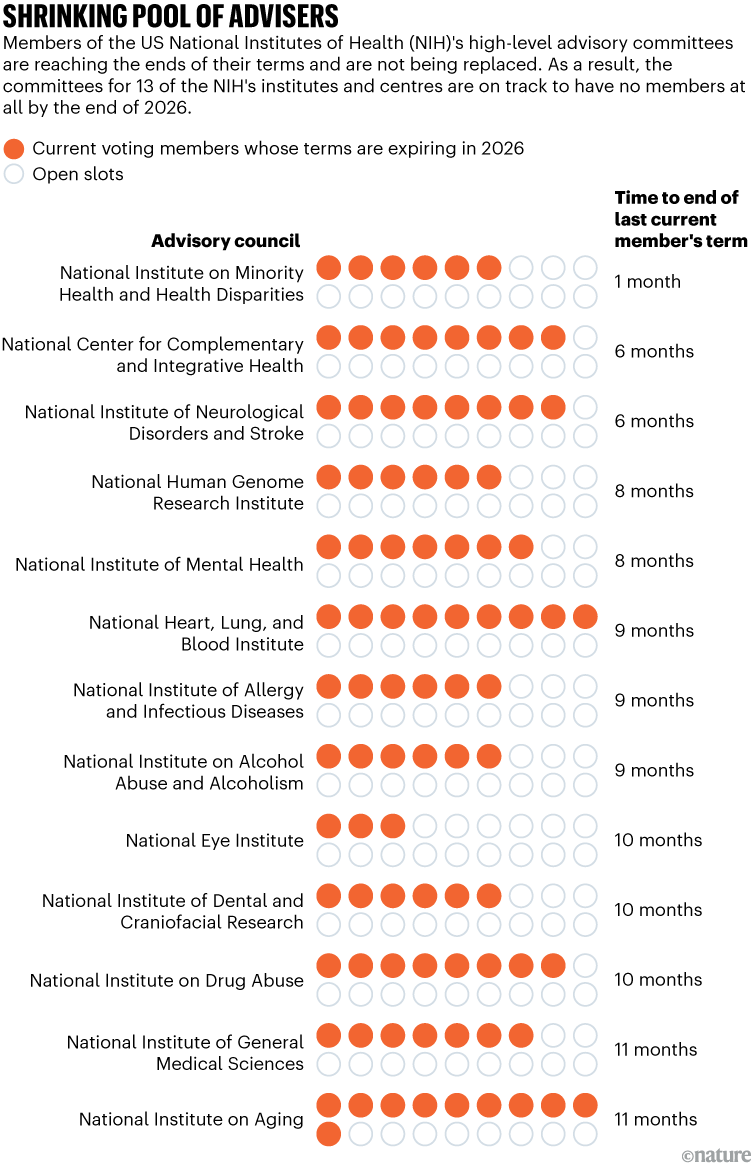

All of the NIH’s 21 institutes and three of its six centres have their own panel, called an advisory council. Membership on the councils has been dwindling as members serve out their terms without replacements being appointed. At 12 of the institutes and one of the centres, the last voting member’s term is set to expire by the end of this year, according to rosters on federal websites (see ‘Shrinking pool of advisers’). It typically takes several years for a new member to be onboarded.

How Trump 2.0 is slashing NIH-backed research — in charts

Dozens of scientists who were poised to fill these vacancies were dismissed last year by the administration of US President Donald Trump, Nature reported in July.

If the advisory councils go dormant, “this could lead to some very big problems for the agency”, says Michael Lauer, who for about ten years ran the NIH’s ‘extramural’ arm, which funds researchers at institutions across the United States. “No grants can get funded without approval from council.”

This comes after the Trump administration blocked and delayed NIH funding in several ways. For example, in early 2025, the administration barred the agency from publishing the notices required to hold grant-review sessions, contributing to a federal watchdog’s finding that the NIH was illegally withholding money allocated by the US Congress.

A spokesperson for the NIH’s parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services, responds that she does not “anticipate any lapse in our ability to make awards”, adding that “we are actively appointing new council members”. Publicly available advisory-council rosters have not been updated with any new members since September, Nature‘s analysis shows.

Independent scrutiny

NIH grant applications are considered in two stages, by separate panels. The first is a study section in which a group of independent scientists meets to score applications. The second is a review by the awarding institute’s advisory council, which consists of scientists and other advisers inside and outside the NIH.

Advisory councils meet three times a year — generally in January, May and either August or October — and make recommendations on applications to the institute’s director, who holds the authority to make the final funding decision. Federal law states that the director of an NIH institute can issue an award only if the grant has been recommended for approval by the advisory council.

Nature examined the official advisory council rosters on the websites of the NIH and the individual institutes, as well as a separate database of federal advisory committees. These sources show that advisory councils for institutes specializing in research on topics such as infectious diseases, ageing and mental health, among others, are on track to have no voting members by the end of the year.

Office of Federal Advisory Committee Policy at US National Institutes of Health

At the advisory council for the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the final voting members’ terms end next month. Without extraordinary action, the council will have no members by its May meeting, when it is scheduled to review grant applications submitted as early as last September — meaning those applications would be effectively frozen.

“Everybody is concerned,” says Jennifer Troyer, who oversaw extramural operations at the National Human Genome Research Institute and resigned in December over concerns about political interference in scientific review at the NIH. When she was at the agency, she regularly met with her counterparts at other NIH institutes and centres and says that “this was a topic that came up every time”.

Staff members are using every tool at their disposal to prevent panels from losing all their members, Troyer says. For example, federal law allows for a single 180-day extension of a panellist’s term if their replacement has not yet joined the council. Nature’s analysis of the rosters finds that about 44% of the 147 members whose terms are set to expire this year have already received this 180-day extension.

Helene Benveniste, a neuroscientist at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, whose term on the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health council will end in July, says she received an inquiry from the NIH about extending her appointment by 180 days. The extension has not been finalized, she says.