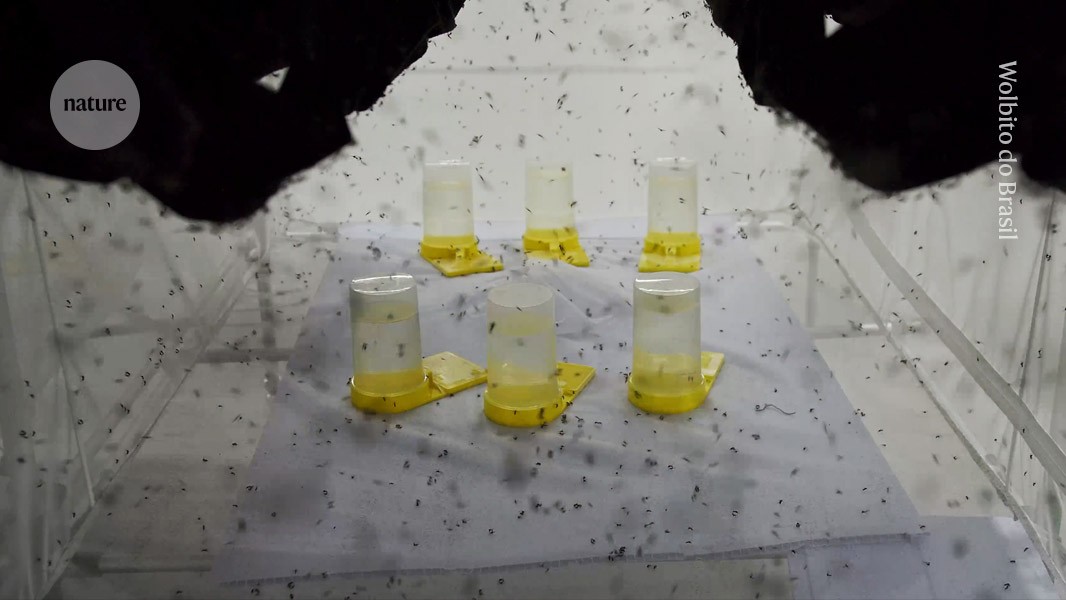

The Wolbito do Brasil factory is breeding Wolbachia-modified mosquitoes, and their eggs will be shipped to Brazilian cities to help reduce disease rates.Credit: Wolbito do Brasil

Curitiba, Brazil

When biologist Antonio Brandão tells people that he works at a mosquito factory, they are often baffled. Why would you make more mosquitoes?, he recalls people asking. “We have enough of them.” But once he explains that the laboratory-raised insects can help to stop the spread of dengue — which strikes hundreds of thousands in Brazil each year with fever, headache and bone pain — they come around.

Dengue rates drop after release of modified mosquitoes in Colombia

Brandão is the production manager, not at just any mosquito factory, but at the world’s largest, located in the southern Brazilian city of Curitiba. Launched in July, the facility is expected to produce 100 million eggs a week from the mosquito Aedes aegypti. However, unlike wild A. aegypti, the main transmitter of dengue virus, those churned out by the factory carry a harmless Wolbachia bacterium that curbs the insects’ ability to spread viruses including dengue and Zika. The idea is to release the modified mosquitoes, which researchers call wolbitos, into cities in Brazil, where they will mate with their wild counterparts and the females will pass the bacterium on to their offspring, gradually converting the local population.

The wolbito strategy, which is being spearheaded by the non-profit World Mosquito Program (WMP), has already shown success in Colombia, Indonesia and at home: in the Brazilian city of Niterói in the southeast, dengue cases dropped by 69% in areas where Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes were released, compared with areas where they weren’t1. Brazil’s federal government has adopted the approach to fight dengue infections — which surged to a record 6.5 million confirmed cases in the country last year — alongside other preventive measures such as vaccines.

When will dengue strike? Outbreaks sync with heat and rain

However, researchers at the factory have discovered that raising millions of the mosquitoes is surprisingly tricky, especially because the insects are fussy about temperature and other factors. Nature visited the Wolbito do Brasil facility — run by a firm formed by the WMP, the Molecular Biology Institute of Paraná and Fiocruz, a research institute affiliated with Brazil’s health ministry — to hear first-hand about the lessons learnt by staff members before they released the factory’s first mosquitoes in late August.

Their hard-won knowledge will inform other efforts to rein in mosquito-borne illnesses around the world, says Gabriela Paz-Bailey, an epidemiologist at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who is based in San Juan, Puerto Rico. “There will be plenty of lessons learned from the Brazilian government involvement in this strategy.”

A factory abuzz with activity

Female A. aegypti mosquitoes need only a small amount of water — a puddle inside an abandoned tyre or bottle cap, for instance — to lay their eggs. This makes it difficult to prevent mosquitoes from breeding in urban areas, but it can also be used to the factory’s advantage. The facility has engineered small, dissolvable capsules, similar to those used for holding medicines, to store around 500 mosquito eggs each. These can be shipped to locations where they are needed, then easily dissolved in small amounts of water for hatching. Fish food is included in the capsules to nourish larvae.

To produce such a large number of eggs in the first place, the factory relies on millions of adult mosquitoes mating and laying eggs around the clock. Researchers ensure that the insects carry a strain of Wolbachia, which can be passed from female mosquitoes to their offspring.

In one of the most impressive rooms at the facility, 66 mesh cages big enough for a human to stand inside hold roughly 10 million mosquitoes in total. Females lay their eggs on strips of paper placed at the bottom of each cage. The tiny black eggs, no bigger than a grain of sand, are collected, and either put into capsules or held for hatching at the facility, to replenish the insects in the cages.

Getting mosquitoes hatched from the eggs to develop inside the controlled facility has been a challenge, however. At each stage of their life cycle, A. aegypti have specific temperature and humidity requirements. Researchers store eggs in a cool but humid room to prevent them from drying out. Larvae, however, require warmer conditions, meaning that the facility needs to shuffle insects to other climate-controlled areas as they develop. “They are very delicate. If you vary some parameters of humidity and temperature, this affects them and impacts their productivity,” says Marlene Salazar, a biologist at the facility.