While plenty of other cities around the world have successfully implemented congestion relief charges to cut down on traffic and pollution, New York City is the first and only U.S. city to give it a try. It’s also one of the few cities in the country with a public transportation system that’s good enough to make such an idea possible in the first place. Despite being in the works for years, congestion relief pricing proved to be plenty controversial before it went into effect. So, 100 days in, how’s Manhattan’s little experiment going? Better than most people could possibly imagine, Curbed reports.

In fact, while fewer cars in the city means life has improved for the people who actually live in New York, the people who still drive into work instead of taking public transportation have also benefited. After all, less traffic means faster travel times, which means car commuters spend less time sitting in traffic. At rush hour, the Holland Tunnel, for example, saw delays drop by 65%, while travel time through the tunnel is down 48%. With fewer cars in the city, MTA Deputy Chief Juliette Michaelson told Curbed doctors have reported fewer late patients, and delivery drivers claim they’re “[saving] so much time.”

On top of that, while support for congestion pricing has risen across the board, a recent Morning Consult poll found the people most in favor of the program were actually the ones who drive into the congestion relief zone the most. As Michaelson put it, “The people who oppose it are folks who live upstate or don’t come in.”

Congestion relief pricing makes life better

For the people who actually live in the city, congestion relief pricing has already proven even more beneficial. Excessive car honking complaints, for example, have dropped about 70% year over year. As it turns out, that’s a statistic New York City actually tracks. Who knew? According to Curbed, the benefits only continue from there:

In those 100 days, 6 million fewer cars drove into lower Manhattan than had done so a year earlier. In March, the decrease was 80,000 per day. In the congestion zone, we’re seeing half as many traffic-related injuries. The bus routes in Manhattan are so much less clogged that the drivers are being forced to slow down to maintain their schedules. (As a rider, I experienced this twice last week, and it was bizarre: a bus moseying along at 5 mph in a wide-open lane. Presumably the schedules will soon be retimed.) The diminished honking is a bonus

Considering the pandemic hurt public transportation ridership and the number of companies disguising layoffs as return-to-office mandates, it’s a little more difficult to figure out how much of the rise in ridership is directly attributable to congestion relief pricing. That said, in January, Metro-North ridership increased by about 300,000 people year over year, up about 8% overall. NJ Transit and the LIRR also saw more riders and a notable increase after the program went into effect on January 5, so it stands to reason that many of those new riders used to be drivers.

Ticket sales for Broadway shows are also up, and New York City’s Business Improvement Districts say year-over-year visits are already up by 1.5 million, so business is indeed still booming.

Where’s the money going?

So far, the biggest pushback against New York’s congestion pricing has come from Republicans in the Trump administration who don’t even live in New York, with the Secretary of Transportation doing his best to kill the program before folding like a cheap suit. Other opponents have resorted to making up imaginary low-wage workers who drive into the city every day and can somehow afford to pay for parking but not the congestion relief charge. That said, considering the program is projected to generate a $500 million profit this year, there are definitely some valid concerns about how the money will be spent.

Sadly, 100 days is far too short a timeline for any of the promised improvements to the city’s public transportation system to have already come to fruition. That said, several projects have already been approved and money allocated for their completion. For example, the Metro station at Delancey Street and Essex Street will finally get three elevators to go along with a 99-unit mixed-use housing development, the Second Avenue subway will now get built out and the city’s placed orders for 265 new electric buses.

On top of that, a list of other projects the program is intended to fund can be found here. Public accountability will continue to be important, but at least for now, that looks like a pretty solid list.

A resounding success

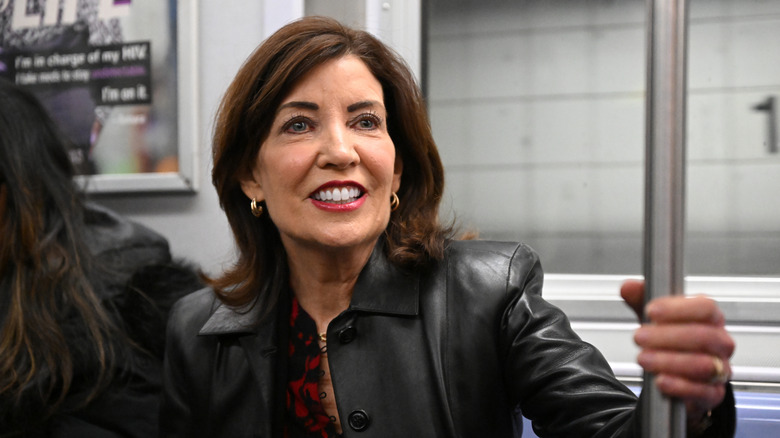

Will people disagree over the best ways to spend the money? Of course. And that’s especially true since Governor Hochul cut the congestion relief charge from the initial $15 down to only $9. And there’s always the chance the Trump administration will find a way to force New York to get rid of the program, but at least so far, it’s hard to see any downsides to the congestion relief zone. The air is getting cleaner, quality of life is improving for New Yorkers, car commuters are saving time, New Jersey’s feelings are hurt, businesses are doing just fine and the city has a new revenue source to fund public transportation improvements.

Will the early results be enough to change the minds of people who hate all cities, Democrats and the entire concept of public transportation? Of course not. No amount of success was ever going to convince people who oppose congestion relief pricing on a purely ideological, partisan level. At the same time, from the MTA’s perspective, the program is no longer an experiment. As Michaelson told Curbed:

“It’s funny — this is a fast-moving environment here at HQ. We were watching the impact of this program extremely closely for the first couple of months, and it’s sort of been incorporated into the fabric; we don’t talk about how the program is doing much anymore. We just continue to look at the numbers, and the numbers continue to look good.”